Archive for the ‘04. + Ecological Jurisprudence’ Category

Tuesday, December 27th, 2022

The printed book’s front cover

“Over the last thirty years (Ed: 1970s – 2000s] the meaning of the word ‘wilderness‘ has changed and come under sustained attack.

How has the term become so confused? What can be done to reduce this confusion?

This book arose from the Ph.D. thesis ‘The Wilderness Knot’ (University of Western Sydney), and investigates the tangled meanings around ‘wilderness’. This ‘knot‘ is comprised of five strands; philosophical, political, cultural, justice and exploitation. ‘Wilderness‘ as a term is in a unique philosophical position, being disliked by both modernists and many postmodernists alike.

The research uses participatory action research with Aboriginal people and conservationists and wilderness journals. All scholars interviewed agreed that large natural intact areas (‘lanais‘) should be protected, though some did not call them ‘wilderness’.

Confusion declines when one can show that people hold many ideas in common. ‘Mind maps’ are used to investigate the issues and to suggest ways forward to reduce confusion. The idea of shared ‘custodianship’ or stewardship is suggested as a way forward.

This is a book for all those interested in saving and managing the Earth’s remaining large natural areas or wilderness.”

~ Haydn Grinling Washington, Ph.D (2009).

Clicking on our document hyperlink below opens to an internal Adobe PDF document stored on this website, which has been downloaded from the University of Western Sydney’s publicly available website, so it resides in the public domain.

This document is available in the public domain because that was the wishes of its author, the late Australian Environmental Scientist Haydn Grinling Washington – to share and promulgate the environmental philosophy of ‘Ecocentrism‘.

This is the opposite of prevailing ‘Anthropocentrism‘ philosophy. Human beings are NOT the central or most important entity in the universe, despite many arrogantly presuming they deserve to be.

Haydn Grinling Washington [1955-2022]

The document comprises his complete Ph.D thesis submitted in 2006.

Later in 2009, Haydn had his successful thesis published as a book entitled ‘The Wilderness Knot: Removing the confusion‘ in the form of a paperback in A4 size of some 386 pages in length, published by VDM Verlag.

The book version is currently still available to be purchased via reputable Internet resellers for a delivered price for about AUD$180. These currently include FruugoAustralia.com and Amazon.com.

This website’s editor knew Haydn from a number of meeting events (2007-2009) within the Australian conservation movement particular to the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and discussed his work and philosophies before Haydn’s untimely succumbing to bowel cancer in December 2022.

Haydn wanted to share his environmental passion for respecting the values and wonder of wilderness, native habitat and its wildlife with as many people as possible. He was not about fame and fortune from his many literary works (his prolific poetry and six books).

Our editor was invited and attended Haydn’s funeral service at The Brahma Kumaris meditation retreat centre in Leura in the Blue Mountains in Australia on Thursday 22nd December 2022. We counted about 150 attendees. It was an opportune time to catch up with seasoned conservationists, although we would have wished for a different reason. Haydn had attended this retreat on a number of occasions.

This is his Ph.D thesis in full, available to read and to download:

READ: >The Wilderness Knot (thesis by Haydn Washington Ph.D 2006 UWS) [This original 386-page PDF document is available for download free of charge, as were Haydn’s wishes].

The printed book’s back cover

Wollemi Wilderness Champion

Haydn Washington dedicated most of his adult life to selected environmental campaigns that affected him in eastern Australia about protecting wilderness areas from human harm, most notably the Wollemi wilderness in the northern part of the Blue Mountains region of New South Wales. Haydn at the time lived nearby, so was this noble planetary Nymyism beyond his backyard?

What is wrong with that? It’s such a selfless cause.

Haydn became the lead campaigner for this vast Wollemi wilderness region of 5,000 km2. He successfully saw it legally protected in 1979 as the Wollemi National Park.

The Wollemi National Park was then in 2000 officially incorporated into the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, respected as one of eight contiguous national park protected areas along with the Blue Mountains, Yengo, Nattai, Kanangra-Boyd, Gardens of Stone and Thirlmere Lakes National Parks, and the Jenolan Karst Conservation Reserve.

Tragically, two decades later from Saturday 26th October 2019 into January 2020 the custodial authority (NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service of NSW (a misnomer) in cahoots with the New South Wales Rural Fire Service) stood back and allowed a private pile-burn off Army Road near Gospers Mountain inside the Wollomi wilderness get out of control and spread over days, weeks and months.

That single ignition was allowed to blanketly incinerate the pristine Wollemi wilderness in its entirety – all 5,000 km2, endangered Koala communities and all! It was wantonly despicable neglectful act by the Wollemi NP’s and Blue Mountains World Heritage Area’s governmental custodian, NPWS.

Indeed this is why we refer to the NPWS organisation as merely the NSW Parks Service; that’s all it is useful for, just servicing parks, as in urban parks and gardens.

NPWS employs no ecologists, no botanists, no zoologists, no ornithologists, no geologists, and no environmental scientists like Haydn Washington; but only public servants.

This is despite NPWS as a state government agency being delegated with supreme responsibility for the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and all other national parks within the Australian state of New South Wales and their threatened and endangered ecosystems within.

Indeed defacto bush arson on a calamitous scale never before in Australia’s history by a anthropocentric governmental culture, having a total disregard and contempt toward Wilderness values.

Haydn would have been utterly devastated.

The entire loss of his favoured wilderness by preventable fire would have sapped him of energy and hope. He lived next to it, knew it intimately by exploration on foot and down the length of the dominant wild Colo River by paddle. One presumes the 2019 bushfire disaster of the Wollemi wilderness caused him immense grief and impacted upon his mental health.

Did wiping out the Wollemi trigger Haydn’s heath demise?

We think so. The physical cause of cancer can emerge from psychological stress.

‘Psychological stress‘ describes what individuals experience when they are under mental, physical, or emotional pressure.

‘Stressors‘ are factors that can cause stress such as negative external factors that arise outside one’s control or influence, such as the total loss of one’s life work to protect a wilderness area and its ecology as an environmental scientist with a deep passion for its ecology. Perhaps his psychological stress had become enduring and chronic, causing translating into physical harm.

Research has shown that people who experience chronic stress can have digestive problems, heart disease, high blood pressure, and a weakened immune system. People who experience chronic stress are also more prone to having headaches, sleep trouble, difficulty concentrating, depression, and anxiety and to getting viral infections. The medical science is out (unschooled) on the causation of cancer from chronic psychological stress.

But what is established is that chronic psychological stress can lead to many health problems. A 2019 meta-analysis of nine observational studies in Europe and North America also found an association between work stress and risk of lung, colorectal, and esophageal cancers. Even when stress appears to be linked to cancer risk, the relationship could be indirect. For example, people under chronic stress may develop certain unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking, overeating, becoming less active, or drinking alcohol, that are themselves associated with increased risks of some cancers. The condition may also prevent the body’s immune system from recognizing and fighting cancer cells.

Three years hence in late 2022, Haydn died of cancer, a chronic disease, at aged just 67, before his time. It is in this editor’s view that the government’s apathetic destruction of the precious Wollemi wilderness by bush arson that Haydn loved so dearly, contributed to the premature demise of his health.

NPWS Blue Mountains Branch Director David Crust had the temerity to present himself at Haydn’s funeral, appropriately donned in a full blackened suit and said nothing. The past Commissioner of the NSW Rural Fire Service, Shane Fitzsimmons who was in charge of the NSW 2019 Bushfire emergencies, including the Wollemi bushfire, did not attend.

Vale Haydn, we’re on to your noble legacy. Your passionate championing of native habitat values and your tireless campaigning fights for the preservation of Wilderness will not have been in vane on this website!

Further Reading:

[1] Vale Haydn Grinling Washington Ph.D [1955-2022], > https://habitatadvocate.com.au/vale-haydn-grinling-washington-ph-d-1955-2022/ , (NOTE: This article is a work in progress and so currently remains unavailable to access, however we expect to have it completed and accessible before the end of January 2023.)

[2] ‘ Stress and Cancer‘, National Cancer Institute, America, 202-10-21 , ^ https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/feelings/stress-fact-sheet

[3] ‘ Dr Haydn Washington’s literary works‘, > https://habitatadvocate.com.au/dr-haydn-washingtons-literary-works/

Tags: Haydn Grinling Washington, lanais, NPWS Director David Crust, NSW RFS, Nymbyism, Ph.D, RFS Commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons, The Wilderness Knot, wilderness

Posted in 04. + Ecological Jurisprudence, Ph03 Ecocentric Ethics, SAVE HABITAT FROM GOVERNMENT ARSON, Threats from Bushfire | 1 Comment »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Friday, April 14th, 2017

Ancient Balga, grass tree, xanthorroea in Dwellingup forest, South West Western Australia. Photo by Jenreflect, 20121104. Ancient Balga, grass tree, xanthorroea in Dwellingup forest, South West Western Australia. Photo by Jenreflect, 20121104.

If we can respectfully wise up and change from calling ‘Ayres Rock’ after an English mining magnate turned politician to ‘Ayers Rock/Uluru’ in 1993, then to ‘Uluru/Ayers Rock’ in 2002, then we can just drop Henry Ayres from the Rock’s association altogether. Henry Ayres was a 19th Century copper mining robber baron who devastated the landscape of Burra in South Australia. A statue in Adelaide near parliament may be appropriate.

Likewise, if we can respectfully wisen up and change from calling this grass tree a ‘black boy’ to calling it a ‘xanthorroea’ then we can call it its traditional name ‘balga’.

“We never catch marron when the creek didn’t run, or the river didn’t run. Always catch marron when the water runs. That’s our culture. You gotta give ’em a chance to breed.

And if you got anything with eggs on ’em, you threw ’em back….We never had nets, yeah, we coulda made nets but we didn’t believe that, you know, you rape the country. So you gotta leave some for the breeding.”

– Partick Hume, 2008, oral history , Kaartdijin Noongar, South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, Western Australia.

‘Aboriginal people, not environmentalists, are our best bet for protecting the planet’

by David Suzuki, published in The Vancouver Sun, 20150608, ^http://www.vancouversun.com/technology/David+Suzuki+Aboriginal+people+environmentalists+best+protecting+planet/11112668/story.html (contributed by our supporters Barbara and Stan).

<<… Using DNA to track the movement of people in the past, scientists suggest our species evolved some 150,000 years ago on the plains of Africa. That was our habitat, but unlike most other animals, we were creative and used our brains to find ways to exploit our surroundings. We were far less impressive in numbers, size, speed, strength or sensory abilities than many others sharing our territory, but it was our brains that compensated.

Over time, our numbers increased and we moved in search of more and new resources (and probably to check out the Neanderthals with whom we crossbred before they went extinct). When we moved into new territories, we were an alien creature, just like the introduced ones that trouble us today.

George Monbiot of The Guardian makes the point that we can trace the movement of our species by a wave of extinction of the big, slow-moving, dim-witted creatures that we could outwit with even the simplest of implements like clubs, pits, and spears.

Our brains were our great evolutionary advantage, conferring massive memory, curiosity, inventiveness and observational powers.

I can’t emphasize that enough.

Our brains gave us a huge advantage and it did something I think is unique — it created a concept of a future, which meant we realized we could affect that future by our actions in the present. By applying our acquired knowledge and insights, we could deliberately choose a path to avoid danger or trouble, and to exploit opportunities. I believe foresight was a huge evolutionary advantage for our species. And that’s what is so tragic today when we have all the amplified foresight of scientists and supercomputers, which have been warning us for decades that we are heading down a dangerous path, but now we allow politics and economics to override this predictive power.

No doubt after we evolved, we quickly eliminated or reduced the numbers of animals and plants for which we found uses. We had no instinctive behavioural traits to restrict or guide our actions — we learned by the consequences of what we did. And all the mistakes that we made and successes that we celebrated were important lessons in the body of accumulating knowledge of a people in a territory.

That was very powerful and critical to understanding our evolutionary success – it was painstakingly acquired experience that became a part of the culture. We are an invasive species all around the world, and I find it amazing that our brains enabled us to move into vastly different ecosystems ranging from steaming jungles to deserts, mountains to arctic tundra, and to flourish on the basis of the painful accumulation of knowledge through trial and error, mistakes, etc.

So it was the people who stayed in place as others moved on, who had to learn to live within their means, or they died. That is what I believe is the basis of indigenous knowledge that has built up over millennia and that will never be duplicated by science because it is acquired from a profoundly different basis (I wrote about the differences in a book, Wisdom of the Elders). The wave of exploration hundreds of years ago brought a very different world view to new lands — North and South America, Africa, Australia — based on a search for opportunity, resources, wealth. There was no respect for flora and fauna except as potential for riches, and certainly no respect for the indigenous people and their cultures. Of course, by outlawing language and culture of indigenous peoples, dominant colonizers attempt to stamp out the cultures which are such impediments to exploitation of the land. Tom King’s book, The Inconvenient Indian, argues very persuasively that policies are to “get those Indians off the land”.

“There was no respect for flora and fauna except as potential for riches, and certainly no respect for the indigenous people and their cultures.”

I think of my grandparents as part of the wave of exploration of the past centuries. They arrived in Canada from Japan between 1902 and 1904. When they came on a harrowing steamship trip, there were no telephones to Japan, no TV, radio, cellphones or computers. They never learned English. They came on a one-way trip to Canada for the promise of opportunity. Their children, my parents, grew up like all the other Japanese-Canadian kids at that time, with no grandparents and no elders. In other words, they had no roots in Japan or Canada. To them, land was opportunity. Work hard, fish, log, farm, mine, use the land to make money. And I believe that is the dominant ethic today and totally at odds with indigenous perspectives.

Remember when battles were fought over drilling in Hecate Strait, supertankers down the coast from Alaska, the dam at Site C, drilling for oil in ANWR, the dam to be built at Altamire in Brazil?

I was involved in small and big ways in these battles, which we thought we won 30 to 35 years ago. But as you know, they are back on the agenda today. So our victories were illusions because we didn’t change the perspective through which we saw the issues.

“Our victories were illusions because we didn’t change the perspective through which we saw the issues.”

That’s what I say environmentalists have failed to do, to use the battles to get people to change their perspectives, and that’s why I have chosen to work with First Nations because in most cases, they are fighting through the value lenses of their culture.

The challenge is to gain a perspective on our place in nature. That’s why I have made one last push to get a ball rolling on the initiative to enshrine the right to a healthy environment in our constitution. It’s a big goal, but in discussing the very idea, we have to ask, what do we mean by a healthy environment. We immediately come to the realization that the most important factor that every human being needs to live and flourish is a breath of air, a drink of water, food and the energy from photosynthesis. Without those elements, we die.

So our healthy future depends on protecting those fundamental needs, which amazingly enough, are cleansed, replenished and created by the web of life itself. So long as we continue to let the economy and political priorities shape the discussion, we will fail in our efforts to find a sustainable future. I have been trying to tell business folk and politicians that, in the battle over the Northern Gateway, what First Nations are trying to tell us is that their opposition is because there are things more important than money.>>

Things more important than Money

Noongar people are the Aboriginal traditional owners of the south-west of Western Australia and have been for over 45,000 years.

<<Noongar boodja (country) extends from north of Jurien Bay, inland to north of Moora and down to the southern coast between Bremer Bay and east of Esperance. It is defined by 14 different areas with varied geography and 14 dialectal groups.

We have a deep knowledge and respect for our country, which has been passed down by our Elders.

Noongar people have a profound physical and spiritual connection to country. It relates to our beliefs and customs regarding creation, life and death, and spirits of the earth. Spiritual connection to country guides the way we understand, navigate and use the land. It also influences our cultural practices.

For thousands of years Noongar people have resided on and had cultural connection to the booja – land. Everything in our vast landscape has meaning and purpose. We speak our own language and have our own lore and customs. The lore is characterised by a strong spiritual connection to country. This means caring for the natural environment and for places of significance. Our lore relates to ceremonies, and to rituals for hunting and gathering when food is abundant and in season. Connection to booja is passed on through our stories, art, song and dance. Noongar people not only survived European colonisation but we thrived as family groups and sought to assert our rights to our booja. For Noongar people, the south-west of Western Australia is ngulla booja – our country.

Noongar lore and custom guide the ways in which we define our country and our rights to it. Lore influences how we connect with and care for the land. As Noongar people we have a duty to speak for our country, to acknowledge its value to our communities and to observe lore that governs who may or may not ‘speak for country’.

Noongar people have always used our knowledge of the six seasons in the south-west of Western Australia to hunt, fish, and gather only the most ripe and abundant food sources for our needs.

The rituals and ceremonies performed by Noongar people over many thousands of years reflect our sustainable use of the environment and reinforce our connection to country. These rituals include domestic and social customs that observe Noongar lore governing the use of land and resources. An important and significant part of Noongar culture is the teaching of sustainable environmental practices, handed down by our Elders.

Being Noongar is to be part of a family and community, which determines our relationship to country. The relationship to country empowers our identity as a Noongar person.>>

Source: ^https://www.noongarculture.org.au/connection-to-country/

Concept of Country Concept of Country

Source: Teaching the Indigenous Concepts of Country and Sustainability (2010), by The Australian Research Institute for Environment and Sustainability (ARIES), ^http://aries.mq.edu.au/projects/deewr_indigenous_concepts/

“We come here to this place here, Minningup, the Collie River, to share the story of this area or what makes it so special. It is the resting place of the Ngangungudditj walgu, the hairy faced snake. Baalap ngany noyt is our spirit and this is where he rests. You have big bearded full moon at night time you can see him, his spirit there, his beard resting in the water. And we come to this place here today to show respect to him plus also to meet our people because when they pass away this is where we come to talk to them. Not to the cemetery where they are buried but here because their spirits are in this water. This is where all our spirits will end up here. Karla koorliny we call it. Coming home. Ngany kurt, ngany karla – our heart, our home. This, our Beeliargu, is the river people. So that’s why we always come to this Minningup. It’s very important.

This is the important part of the river, of the whole Collie River and the Preston River and the Brunswick River, because he created all them rivers and all the waters but here is the most important because this is where he rest. So whenever we come back now – my cousin died the other day so we come back here, bring his spirit home because this is where he belong here. They will bury him with his mother and you sing out to him. Ngany moort koorliny. Ngany waanginy, dadjinin waanginy kaartdijin djurip. And we come and look there and talk to you old fellow. Your people have come back. Ngany waangkaniny. I talk now. Balap kaartdijin. Listen, listen. Palanni waangkaniny. Ngany moort koorliny noonook. Ngany moort wanjanin. Your people come to rest with you now. Listen old fellow, listen for ’em, bring them home. Karla koorliny. Bring them home and then you sing to them. (Singing in language) And then chuck sand to land in the water so he can smell you. That’s our rules. Beeliargu moort. That’s the river people. That’s why this place important.”

– Joe Northover talks about Minningup Pool on the Collie River, ^https://www.noongarculture.org.au/connection-to-country/

Me, me, me anthropocentrism is so robber baron babyboomer. Learn about ecocentrism. Caring For Country starts with respect and perhaps respecting that 45,000 years of connection has shown that there are six seasons in Noongar – Birak, Bunuru, Djeran, Makuru, Djilba, Kambarang. (Ed.)

Saturday, September 17th, 2011

Play music, then click back to this site, zoom in to make the photos larger and scroll through this article and appreciate the magic of what was Lake Pedder. Play music, then click back to this site, zoom in to make the photos larger and scroll through this article and appreciate the magic of what was Lake Pedder.

.

The pristine glacial lake it once was.

The jewel of Tasmania’s primeval sacred ecology.

.

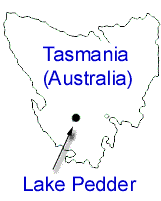

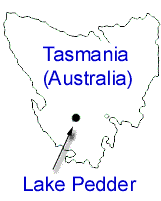

Lake Pedder

(Photo by Olegas Truchanas (1923-1972) Lake Pedder

(Photo by Olegas Truchanas (1923-1972)

.

This photo currently appropriated on the website of Tasmanian Resource Planning and Development Commission,

which as the ‘Hydro-Electric Commission’ flooded the lake in 1972 and which oddly uses the word ‘justice’ in its web address.

^http://soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/image/544/index.php This photo currently appropriated on the website of Tasmanian Resource Planning and Development Commission,

which as the ‘Hydro-Electric Commission’ flooded the lake in 1972 and which oddly uses the word ‘justice’ in its web address.

^http://soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/image/544/index.php

New Book Release:

.

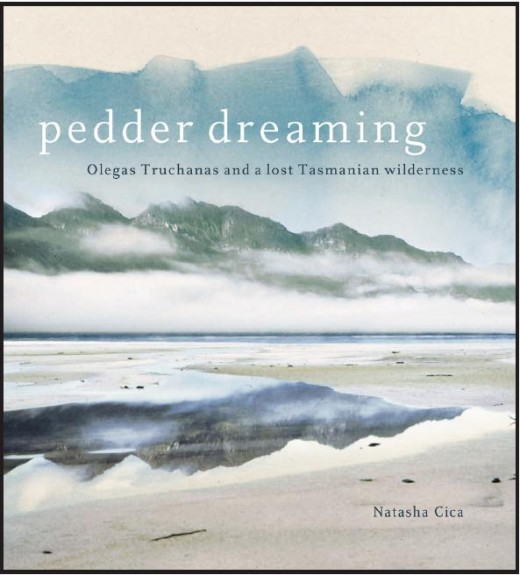

‘Pedder Dreaming: Olegas Truchanas and a lost Tasmanian Wilderness’

by Natasha Cica, September 2011 | ISBN 978 0 7022 3672 3 | RRP:$59.95, | 230mm x 203 mm | Illustrated | 256pp (full colour) | Published by UQP | [Read More]

.

‘In 1972 Lake Pedder in Tasmania’s untamed south-west was flooded to build a dam.

Wilderness photographer Olegas Truchanas, who had spent years campaigning passionately to save the magnificent fresh water lake, had finally lost.

The campaign, the first of its kind in Australia, paved the way for later conservation successes, and turned Truchanas into a Tasmanian legend. Pedder Dreaming quietly evokes the man, the time and the place.

Truchanas, a Lithuanian émigré, is a stalwart adventurer, loving family man, activist, thinker, survivor and artist. Australia on the cusp of environmental awareness is the time, and Lake Pedder and the south-west of Tasmania, the place – wild, pristine, wondrous.

Through those who were closest to him, Truchanas emerges, as does his influence on early conservation in Tasmania, and the small group of landscape artists, the Sunday Group, who admired his passion for the lake and were inspired by it. Stunningly illustrated with original Truchanas photographs from the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, and artwork from the Sunday Group, Pedder Dreaming captures the brutality, raw beauty and vulnerability of the Tasmanian wilderness and the legacy of one man who had the vision to fight for it.’

What we destroyed… Olegas Truchanas’ children playing in Lake Pedder in Tasmania’s Southwest in 1971. Less that 12 months later it was flooded. What we destroyed… Olegas Truchanas’ children playing in Lake Pedder in Tasmania’s Southwest in 1971. Less that 12 months later it was flooded.

In 1974 the head of the Lake Pedder Committee of Enquiry, Edward St John QC would famously claim “The day will come when our children will undo what we so foolishly have done.”

.

Fake Pedder ~ today’s drowned lake Fake Pedder ~ today’s drowned lake

.

.

About Olegas Truchanas

.

Olegas Truchanas, a Lithuanian born in 1923, emigrated to Tasmania after World War II, during which he fought with the Lithuanian resistance and spent time in displaced persons’ camps in Allied-occupied Germany.

From the 1950s, Olegas photographed Tasmania’s remote south-west wilderness, frequently travelling solo and risking his life in order to do so. He also met and married a Tasmanian, Melva, and together they built a house and had three children.

Through his photography, Olegas established a salon-style connection with a circle of Tasmanian photographers and watercolour painters known as the Sunday Group, and he worked with them to save a remote glacial lake with pale pink sands – Lake Pedder – from inundation by a hydroelectric scheme.

This was Australia’s “first globally noticed environmental battle, and later produced the world’s “first greens party. The campaign failed and the lake was lost. Soon afer, in early 1972, Olegas drowned while on a photographic expedition to one of Tasmania’s wildest rivers.

.

.

Remembering Lake Pedder

.

Play two rare videos of Lake Pedder by ABC Television just before the flooding:

Turn up your computer volume, then click one image at a time.

. .

.

.

‘What Lake Pedder taught me’

by Brian Holden, 20081023, ^http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=8057&page=2

.

‘It has gone, and after thousands of years of being, I was one of the last to absorb its magnificence. I still find it hard to believe that I was so fortunate. Lake Pedder February 1972 has become my dreamtime. It was for me a feeling of timelessness and a feeling of being in the type of place we were all meant to be.’

. .

What Lake Pedder taught me

‘Boneheaded politicians will only do what we let them get away with. One of our crown jewels was able to be destroyed for almost no gain because the public at large have become alien to the planet. It is normal to consume and pollute. It is normal to be stressed and in a spiritual void. We are lemmings racing towards the cliff edge – and there can be no turning back.’

.

.

‘Hydro Past Constrains Future’

by Peter Fagan, 20091027, Tasmanian Times newspaper, ^http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php?/weblog/article/professor-west-reminds-tasmania-that-hydro-past-constrains-future/

.

‘Whatever else Tasmanians agree or disagree with in Professor West’s report, they should be grateful for this timely reminder that hydro-industrialisation continues to impose heavy costs on their state. In dollar terms alone, the sale of electricity to these industrial users below cost and way below potential value is costing the State Government up to $220 million in revenue every year.

If two-thirds of Tasmania’s annual electricity generation was to be freed up for purposes other than powering these old and highly energy-intensive plants, a range of options and opportunities would be available.

For example:

- A great deal more of the hydro electricity generated could be sold at peak times and peak tariffs via Basslink to mainland Australia

- Electricity production could be reduced whenever the hydro storage reservoirs were depleted by drought, restoring some degree of energy security to the system

- The ability of the hydro system to make electricity availabile instantly could enable integration of substantially more eco-friendly wind power into the Tasmanian and national grids – if this one isn’t clear to you the problem space is outlined in these Wikipedia articles:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Load_following_power_plant

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intermittent_power_source

.

The most intriguing possibility that gaining control of its electrical energy resource would afford Tasmania is the opportunity to revisit the restoration of Lake Pedder. Draining all or part of the Huon-Serpentine impoundment (the “new” Lake Pedder) need cost less than 20% of the electricity generation capacity of the Middle Gordon Scheme.

.

Restoration of the Lake would bring enormous benefits to Tasmania

.

Remember – less than 60 air miles from Hobart, one of the natural wonders of the world lies under less than 40 feet of water. It is submerged in a massive diversion pond (NOT a storage) whose sole purpose is to transfer water to a hydro power station, two thirds of whose output is gifted, below cost and way below potential value, to old-tech secondary industry.

Professor West’s recommendation serves to remind Tasmanians that what had become the political, social, economic and environmental nightmare of hydro-industrialisation did not end when the High Court ruled out the construction of the Gordon-below Franklin dam in July 1983. More than 25 years later, Tasmania – Australia’s poorest state – a rich island full of relatively poor people – continues to bleed revenue and incur household and business energy costs, social costs, environmental costs and opportunity costs resulting from the excesses of hydro-industrialisation.’

The case for restoration of Lake Pedder and a wealth of other resources are available from the Lake Pedder Restoration Committee web site: www.lakepedder.org

.

.

‘Lake Pedder: the beginning of a movement’

by Natasha Simons, Green Left, 19920930, ^http://www.greenleft.org.au/node/2943

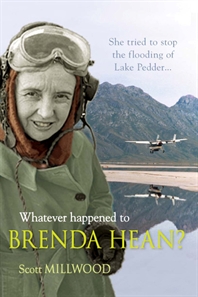

‘On September 8, 1972, Brenda Hean and Max Price, members of the Lake Pedder Action Group, waved goodbye to friends and relatives as their Tiger Moth plane taxied down the airstrip just outside Hobart. Their mission was to fly to Canberra and skywrite the message “Save Lake Pedder” to the federal government in an effort to stop the flooding of the lake. They have been missing ever since.

Twenty years ago the campaign to save Lake Pedder was lost, but its lessons were well learned by the new green movement. The fight to save Lake Pedder laid the foundations for the overwhelming success of the Franklin “no dams!” campaign in the early 1980s, and it inspired many environmental activists — some of whom, such as Bob Brown, hold seats in Parliament today.

Lake Pedder, in Tasmania’s wild south-west, is considered by many to be one of the most beautiful regions in the world. By 1946 Pedder had become a base for expeditions into all parts of the south-west. In 1955, 24 000 hectares were set aside as the Lake Pedder National Park. Bushwalkers, tourists and nature lovers came from afar to experience the beauty of Lake Pedder.

In 1967 the Hydro-Electric Commission proposed to build a power scheme in the Middle Gordon. This meant that Lake Pedder would be drowned by the damming of the Huon and Serpentine Rivers, which lay to the east and west of the lake.

In May 1967, the proposal was tabled in the state parliament. There was an immediate public outcry. Lake Pedder supporters began a petition to stop the proposal and collected 10,000 signatures, the largest number that had ever been collected in Tasmania. As the pressure mounted, the Labor government of “Electric Eric” Reece was forced to establish a select committee to determine the viability of the HEC proposal, and to look at alternatives.

However, the committee merely rubber-stamped the proposal. Two days later, on August 24, 1967, the enabling legislation was passed. Then the campaign to save Lake Pedder really began.

In 1969 the Reece government lost office in the wake of public discontent over the issue and the new government, a coalition of the Liberal and Centre parties headed by Angus Bethune, found itself in a difficult situation.

.

In March 1971 Brenda Hean and Louis Shoobridge, two prominent campaigners for Lake Pedder, organised a public meeting which packed the Hobart Town Hall.

Public opinion on the issue had polarised.

The public meeting proposed to call a referendum on the issue, but the “Shoobridge proposal”, as it became known, was defeated by a government wholeheartedly backing the HEC.

.

The grassroots activists refused to give up. They formed the Lake Pedder Action Group (LPAG), which took the issue to the federal government. As a result, Prime Minister William McMahon directed his unsympathetic environment minister, Peter Howsden, to raise an alternative scheme with Bethune. The Tasmanian premier responded with a resounding “No”.

Just as it seemed things were lost, the Bethune government was forced to the polls, and the environmentalists seized the opportunity. Again a public meeting was called in the Hobart Town Hall. Out of it the first green party, the United Tasmania Group (UTG), was formed. The UTG fielded candidates, among them Brenda Hean, with very diverse backgrounds but who were united in their desire to save Lake Pedder from the HEC.

The UTG polled well and, despite HEC attempts to discredit the campaign, Lake Pedder gained international attention, including support from organisations such as UNESCO. On July 24, 1972, 17,500 signatures reached the new premier, and the LPAG mounted a national campaign.

A few days before Brenda Hean and Max Price set off for Canberra, Hean had received an anonymous phone call from someone pressuring her to give up the campaign or “go for a swim”. The plane hangar was found to have been broken into and the safety beacon, normally stored on the plane, had been removed. There was never a proper inquiry into the case and no wreckage was ever found.

The Pedder campaigners now put their hopes on the newly elected federal Labor government, which mounted a federal-state inquiry. The Tasmanian government refused to participate, but the committee in June 1973 reported the area was too important to destroy. The inquiry recommended a moratorium on flooding so that the feasibility of saving the lake could be addressed. It adopted LPAG’s recommendations to pay the costs of the moratorium and any costs of modifying the scheme to save the lake. The weary LPAG activists could sense victory.

But the premier ignored the inquiry and gave the HEC the go-ahead. In March 1973 the vigil camp to save wildlife threatened by the rising waters was abandoned, and Lake Pedder was drowned. Tasmanian environmentalists had suffered their first great defeat.

In 1979, the HEC released details of another proposal, this time to flood the Franklin River, one of the last great wilderness areas in the world. This time it was met by a much tougher, more unified and stronger opposition.

The Franklin activists, headed by figures like Bob Brown, had learned how to run a campaign. They didn’t only argue that the Franklin should be saved, as the Pedder campaigners had done; they also presented a range of alternative and well thought-out proposals to the HEC. They gained national and international support for their campaign and employed direct action tactics as well. The Franklin was one of the biggest actions of civil disobedience the country had ever witnessed, with 1217 people arrested.

The Franklin blockade polarised the community on the West Coast. The issue tore the Tasmanian ALP apart, and it has never fully recovered from the blow.

The Franklin campaign was won, and in 1986 Bob Brown was elected to state parliament on a wave of green consciousness. Three years later, during which time the campaign for Wesley Vale was fought and won, he was joined by four other Green Independents.

“The failure of Lake Pedder was needed in a way”, says Green Independent Christine Milne, “to allow the fights for the Franklin and Wesley Vale to succeed. When the lake went under, there was a wide sense of guilt that made people feel they would never again allow that to happen without doing something.”

The momentum built up during the Lake Pedder and Franklin campaigns has been lost to the green movement in recent times. The electoral strategy of some sections has changed the focus from mobilising people to making changes through parliament. Lobbying the ALP has also proven largely ineffective for, while the federal Labor government has espoused green rhetoric, it has for the most part ignored environmental issues.

The recession has pushed the issue of living standards and jobs to the forefront. Big business, the government and the media all counterpose jobs to saving the environment, trying to drive a wedge between environmental and social justice issues.

The creation of jobs and defence of living standards need to be at the forefront of the green agenda, with the emphasis on environmentally sustainable jobs. By taking up more of the social justice agenda, the green movement may link up with others fighting for social change and revive the grassroots activity that can challenge the powers that be.’

.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘Pedder Dreaming’ – media release [ Read More]

[2] ‘Pedder Dreaming’ book launches [ Read More]

[3] Lake Pedder Restoration Committee, ^http://www.lakepedder.org/index.html

[4] Lake Pedder – an overview of its history^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Pedder

[5] ‘ Remember Lake Pedder?‘, by Robert Rankin^ http://www.rankin.com.au/essay7.htm

[6] ‘ Lake Pedder‘, Timeframe,^ http://www.abc.net.au/science/kelvin/files/s18.htm

[7] Lake Pedder Earthworm, ^ http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=83060

[8] Lake Pedder Report, presented by ABC Four Corners, 19710424, ^ http://www.abceducation.net.au/videolibrary/view/lake-pedder-report-126 [ View Video as mp4 – ensure volume is turned up first]

[9] Lake Pedder’s Future’ , by Peter Ross, ABC TV, This Day Tonight, 19720704, ^ http://abceducation.net.au/~abceduca/videolibrary/view/lake-pedders-future-74 [ View Video – ensure volume is turned up first]

[10] ‘ Whatever happened to Brenda Hean?‘ ^ http://www.abc.net.au/atthemovies/txt/s2367992.htm

[11] ‘ Whatever happened to Brenda Hean?‘, by Scott Millwood, ^ http://www.allenandunwin.com/default.aspx?page=94&book=9781741756111

Remembering Brenda Hean

In ‘Pedder’, Brenda had found her spiritual centre. Remembering Brenda Hean

In ‘Pedder’, Brenda had found her spiritual centre.

.

.

Tags: Brenda Hean, Eric Reece, fake pedder, green movement, HEC, Hydro-Electric Commission, Lake Pedder, Lake Pedder Action Group (LPAG), Lake Pedder Restoration Committee, Louis Shoobridge, Middle Gordon Scheme, Olegas Truchanas, Pedder Dreaming, Tasmania, the jewel of Tasmania's sacred primeval ecology, the victim of an ignorant time

Posted in 04. + Ecological Jurisprudence, 32 Ecosystem Rehabilitation!, Tasmania (AU), Threats from Hydro and Dams, Threats to Wild Tasmania | Comments Off on Lake Pedder – the victim of an ignorant time

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

|

|