Lake Pedder – the victim of an ignorant time

Saturday, September 17th, 2011 Play music, then click back to this site, zoom in to make the photos larger and scroll through this article and appreciate the magic of what was Lake Pedder.

Play music, then click back to this site, zoom in to make the photos larger and scroll through this article and appreciate the magic of what was Lake Pedder..

The pristine glacial lake it once was.

The jewel of Tasmania’s primeval sacred ecology.

.

Lake Pedder

(Photo by Olegas Truchanas (1923-1972)

Lake Pedder

(Photo by Olegas Truchanas (1923-1972)

.

This photo currently appropriated on the website of Tasmanian Resource Planning and Development Commission,

which as the ‘Hydro-Electric Commission’ flooded the lake in 1972 and which oddly uses the word ‘justice’ in its web address.

^http://soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/image/544/index.php

This photo currently appropriated on the website of Tasmanian Resource Planning and Development Commission,

which as the ‘Hydro-Electric Commission’ flooded the lake in 1972 and which oddly uses the word ‘justice’ in its web address.

^http://soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/image/544/index.php

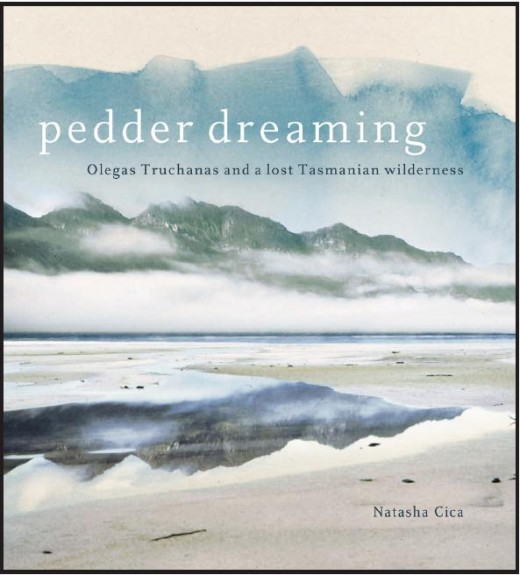

New Book Release:

.

‘Pedder Dreaming: Olegas Truchanas and a lost Tasmanian Wilderness’

by Natasha Cica, September 2011 | ISBN 978 0 7022 3672 3 | RRP:$59.95, | 230mm x 203 mm | Illustrated | 256pp (full colour) | Published by UQP | [Read More].

‘In 1972 Lake Pedder in Tasmania’s untamed south-west was flooded to build a dam.

Wilderness photographer Olegas Truchanas, who had spent years campaigning passionately to save the magnificent fresh water lake, had finally lost.

The campaign, the first of its kind in Australia, paved the way for later conservation successes, and turned Truchanas into a Tasmanian legend. Pedder Dreaming quietly evokes the man, the time and the place.

Truchanas, a Lithuanian émigré, is a stalwart adventurer, loving family man, activist, thinker, survivor and artist. Australia on the cusp of environmental awareness is the time, and Lake Pedder and the south-west of Tasmania, the place – wild, pristine, wondrous.

Through those who were closest to him, Truchanas emerges, as does his influence on early conservation in Tasmania, and the small group of landscape artists, the Sunday Group, who admired his passion for the lake and were inspired by it. Stunningly illustrated with original Truchanas photographs from the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, and artwork from the Sunday Group, Pedder Dreaming captures the brutality, raw beauty and vulnerability of the Tasmanian wilderness and the legacy of one man who had the vision to fight for it.’

What we destroyed… Olegas Truchanas’ children playing in Lake Pedder in Tasmania’s Southwest in 1971. Less that 12 months later it was flooded.

What we destroyed… Olegas Truchanas’ children playing in Lake Pedder in Tasmania’s Southwest in 1971. Less that 12 months later it was flooded.

In 1974 the head of the Lake Pedder Committee of Enquiry, Edward St John QC would famously claim “The day will come when our children will undo what we so foolishly have done.”

.

Fake Pedder ~ today’s drowned lake

Fake Pedder ~ today’s drowned lake

.

.

About Olegas Truchanas

.

Olegas Truchanas, a Lithuanian born in 1923, emigrated to Tasmania after World War II, during which he fought with the Lithuanian resistance and spent time in displaced persons’ camps in Allied-occupied Germany.

From the 1950s, Olegas photographed Tasmania’s remote south-west wilderness, frequently travelling solo and risking his life in order to do so. He also met and married a Tasmanian, Melva, and together they built a house and had three children.

Through his photography, Olegas established a salon-style connection with a circle of Tasmanian photographers and watercolour painters known as the Sunday Group, and he worked with them to save a remote glacial lake with pale pink sands – Lake Pedder – from inundation by a hydroelectric scheme.

This was Australia’s “first globally noticed environmental battle, and later produced the world’s “first greens party. The campaign failed and the lake was lost. Soon afer, in early 1972, Olegas drowned while on a photographic expedition to one of Tasmania’s wildest rivers.

.

.

Remembering Lake Pedder

.

Play two rare videos of Lake Pedder by ABC Television just before the flooding:

Turn up your computer volume, then click one image at a time. .

.

.

.

‘What Lake Pedder taught me’

by Brian Holden, 20081023, ^http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=8057&page=2.

‘It has gone, and after thousands of years of being, I was one of the last to absorb its magnificence. I still find it hard to believe that I was so fortunate. Lake Pedder February 1972 has become my dreamtime. It was for me a feeling of timelessness and a feeling of being in the type of place we were all meant to be.’

.

.

What Lake Pedder taught me

‘Boneheaded politicians will only do what we let them get away with. One of our crown jewels was able to be destroyed for almost no gain because the public at large have become alien to the planet. It is normal to consume and pollute. It is normal to be stressed and in a spiritual void. We are lemmings racing towards the cliff edge – and there can be no turning back.’

.

.

‘Hydro Past Constrains Future’

by Peter Fagan, 20091027, Tasmanian Times newspaper, ^http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php?/weblog/article/professor-west-reminds-tasmania-that-hydro-past-constrains-future/.

‘Whatever else Tasmanians agree or disagree with in Professor West’s report, they should be grateful for this timely reminder that hydro-industrialisation continues to impose heavy costs on their state. In dollar terms alone, the sale of electricity to these industrial users below cost and way below potential value is costing the State Government up to $220 million in revenue every year.

If two-thirds of Tasmania’s annual electricity generation was to be freed up for purposes other than powering these old and highly energy-intensive plants, a range of options and opportunities would be available.

For example:

- A great deal more of the hydro electricity generated could be sold at peak times and peak tariffs via Basslink to mainland Australia

- Electricity production could be reduced whenever the hydro storage reservoirs were depleted by drought, restoring some degree of energy security to the system

- The ability of the hydro system to make electricity availabile instantly could enable integration of substantially more eco-friendly wind power into the Tasmanian and national grids – if this one isn’t clear to you the problem space is outlined in these Wikipedia articles:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Load_following_power_plant

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intermittent_power_source

.

The most intriguing possibility that gaining control of its electrical energy resource would afford Tasmania is the opportunity to revisit the restoration of Lake Pedder. Draining all or part of the Huon-Serpentine impoundment (the “new” Lake Pedder) need cost less than 20% of the electricity generation capacity of the Middle Gordon Scheme.

.

Restoration of the Lake would bring enormous benefits to Tasmania

.

Remember – less than 60 air miles from Hobart, one of the natural wonders of the world lies under less than 40 feet of water. It is submerged in a massive diversion pond (NOT a storage) whose sole purpose is to transfer water to a hydro power station, two thirds of whose output is gifted, below cost and way below potential value, to old-tech secondary industry.

Professor West’s recommendation serves to remind Tasmanians that what had become the political, social, economic and environmental nightmare of hydro-industrialisation did not end when the High Court ruled out the construction of the Gordon-below Franklin dam in July 1983. More than 25 years later, Tasmania – Australia’s poorest state – a rich island full of relatively poor people – continues to bleed revenue and incur household and business energy costs, social costs, environmental costs and opportunity costs resulting from the excesses of hydro-industrialisation.’

The case for restoration of Lake Pedder and a wealth of other resources are available from the Lake Pedder Restoration Committee web site: www.lakepedder.org

.

.

‘Lake Pedder: the beginning of a movement’

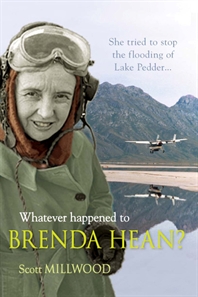

by Natasha Simons, Green Left, 19920930, ^http://www.greenleft.org.au/node/2943‘On September 8, 1972, Brenda Hean and Max Price, members of the Lake Pedder Action Group, waved goodbye to friends and relatives as their Tiger Moth plane taxied down the airstrip just outside Hobart. Their mission was to fly to Canberra and skywrite the message “Save Lake Pedder” to the federal government in an effort to stop the flooding of the lake. They have been missing ever since.

Twenty years ago the campaign to save Lake Pedder was lost, but its lessons were well learned by the new green movement. The fight to save Lake Pedder laid the foundations for the overwhelming success of the Franklin “no dams!” campaign in the early 1980s, and it inspired many environmental activists — some of whom, such as Bob Brown, hold seats in Parliament today.

Lake Pedder, in Tasmania’s wild south-west, is considered by many to be one of the most beautiful regions in the world. By 1946 Pedder had become a base for expeditions into all parts of the south-west. In 1955, 24 000 hectares were set aside as the Lake Pedder National Park. Bushwalkers, tourists and nature lovers came from afar to experience the beauty of Lake Pedder.

In 1967 the Hydro-Electric Commission proposed to build a power scheme in the Middle Gordon. This meant that Lake Pedder would be drowned by the damming of the Huon and Serpentine Rivers, which lay to the east and west of the lake.

In May 1967, the proposal was tabled in the state parliament. There was an immediate public outcry. Lake Pedder supporters began a petition to stop the proposal and collected 10,000 signatures, the largest number that had ever been collected in Tasmania. As the pressure mounted, the Labor government of “Electric Eric” Reece was forced to establish a select committee to determine the viability of the HEC proposal, and to look at alternatives.

However, the committee merely rubber-stamped the proposal. Two days later, on August 24, 1967, the enabling legislation was passed. Then the campaign to save Lake Pedder really began.

In 1969 the Reece government lost office in the wake of public discontent over the issue and the new government, a coalition of the Liberal and Centre parties headed by Angus Bethune, found itself in a difficult situation.

.

In March 1971 Brenda Hean and Louis Shoobridge, two prominent campaigners for Lake Pedder, organised a public meeting which packed the Hobart Town Hall.

Public opinion on the issue had polarised.

The public meeting proposed to call a referendum on the issue, but the “Shoobridge proposal”, as it became known, was defeated by a government wholeheartedly backing the HEC.

.

The grassroots activists refused to give up. They formed the Lake Pedder Action Group (LPAG), which took the issue to the federal government. As a result, Prime Minister William McMahon directed his unsympathetic environment minister, Peter Howsden, to raise an alternative scheme with Bethune. The Tasmanian premier responded with a resounding “No”.

Just as it seemed things were lost, the Bethune government was forced to the polls, and the environmentalists seized the opportunity. Again a public meeting was called in the Hobart Town Hall. Out of it the first green party, the United Tasmania Group (UTG), was formed. The UTG fielded candidates, among them Brenda Hean, with very diverse backgrounds but who were united in their desire to save Lake Pedder from the HEC.

The UTG polled well and, despite HEC attempts to discredit the campaign, Lake Pedder gained international attention, including support from organisations such as UNESCO. On July 24, 1972, 17,500 signatures reached the new premier, and the LPAG mounted a national campaign.

A few days before Brenda Hean and Max Price set off for Canberra, Hean had received an anonymous phone call from someone pressuring her to give up the campaign or “go for a swim”. The plane hangar was found to have been broken into and the safety beacon, normally stored on the plane, had been removed. There was never a proper inquiry into the case and no wreckage was ever found.

The Pedder campaigners now put their hopes on the newly elected federal Labor government, which mounted a federal-state inquiry. The Tasmanian government refused to participate, but the committee in June 1973 reported the area was too important to destroy. The inquiry recommended a moratorium on flooding so that the feasibility of saving the lake could be addressed. It adopted LPAG’s recommendations to pay the costs of the moratorium and any costs of modifying the scheme to save the lake. The weary LPAG activists could sense victory.

But the premier ignored the inquiry and gave the HEC the go-ahead. In March 1973 the vigil camp to save wildlife threatened by the rising waters was abandoned, and Lake Pedder was drowned. Tasmanian environmentalists had suffered their first great defeat.

In 1979, the HEC released details of another proposal, this time to flood the Franklin River, one of the last great wilderness areas in the world. This time it was met by a much tougher, more unified and stronger opposition.

The Franklin activists, headed by figures like Bob Brown, had learned how to run a campaign. They didn’t only argue that the Franklin should be saved, as the Pedder campaigners had done; they also presented a range of alternative and well thought-out proposals to the HEC. They gained national and international support for their campaign and employed direct action tactics as well. The Franklin was one of the biggest actions of civil disobedience the country had ever witnessed, with 1217 people arrested.

The Franklin blockade polarised the community on the West Coast. The issue tore the Tasmanian ALP apart, and it has never fully recovered from the blow.

The Franklin campaign was won, and in 1986 Bob Brown was elected to state parliament on a wave of green consciousness. Three years later, during which time the campaign for Wesley Vale was fought and won, he was joined by four other Green Independents.

“The failure of Lake Pedder was needed in a way”, says Green Independent Christine Milne, “to allow the fights for the Franklin and Wesley Vale to succeed. When the lake went under, there was a wide sense of guilt that made people feel they would never again allow that to happen without doing something.”

The momentum built up during the Lake Pedder and Franklin campaigns has been lost to the green movement in recent times. The electoral strategy of some sections has changed the focus from mobilising people to making changes through parliament. Lobbying the ALP has also proven largely ineffective for, while the federal Labor government has espoused green rhetoric, it has for the most part ignored environmental issues.

The recession has pushed the issue of living standards and jobs to the forefront. Big business, the government and the media all counterpose jobs to saving the environment, trying to drive a wedge between environmental and social justice issues.

The creation of jobs and defence of living standards need to be at the forefront of the green agenda, with the emphasis on environmentally sustainable jobs. By taking up more of the social justice agenda, the green movement may link up with others fighting for social change and revive the grassroots activity that can challenge the powers that be.’

.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘Pedder Dreaming’ – media release [Read More] [2] ‘Pedder Dreaming’ book launches [Read More][3] Lake Pedder Restoration Committee, ^http://www.lakepedder.org/index.html

[4] Lake Pedder – an overview of its history^http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Pedder [5] ‘Remember Lake Pedder?‘, by Robert Rankin^http://www.rankin.com.au/essay7.htm [6] ‘Lake Pedder‘, Timeframe,^http://www.abc.net.au/science/kelvin/files/s18.htm [7] Lake Pedder Earthworm, ^http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=83060 [8] Lake Pedder Report, presented by ABC Four Corners, 19710424, ^http://www.abceducation.net.au/videolibrary/view/lake-pedder-report-126 [View Video as mp4 – ensure volume is turned up first] [9] Lake Pedder’s Future’ , by Peter Ross, ABC TV, This Day Tonight, 19720704, ^http://abceducation.net.au/~abceduca/videolibrary/view/lake-pedders-future-74 [View Video – ensure volume is turned up first] [10] ‘Whatever happened to Brenda Hean?‘ ^http://www.abc.net.au/atthemovies/txt/s2367992.htm [11] ‘Whatever happened to Brenda Hean?‘, by Scott Millwood, ^http://www.allenandunwin.com/default.aspx?page=94&book=9781741756111 Remembering Brenda Hean

In ‘Pedder’, Brenda had found her spiritual centre.

Remembering Brenda Hean

In ‘Pedder’, Brenda had found her spiritual centre.