The Getting of Wisdom

Saturday, February 19th, 2011‘The Getting of Wisdom‘ is a well-known Australian novel published in 1910 by Australian novelist Henry Handel Richardson [a pen name for Ethel Florence Lindsay Richardson]. According to Wikipedia, Richardson was a writer born into wealth in 1870, but who fell on hard times. The novel is based on this life changing experience, social expectations, coping with social shame and the destruction of innocence.

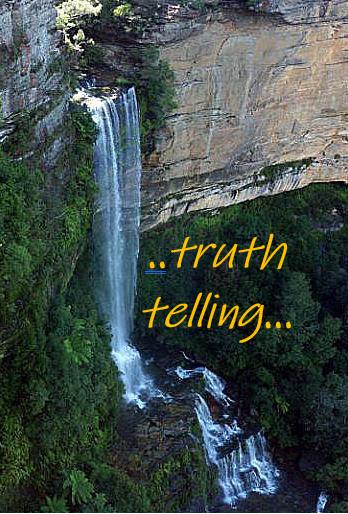

Gandalf, The Lord of the Rings

Gandalf, The Lord of the Rings

.

Vice-chancellor of Macquarie University, Steven Schwartz, picked up on this theme in a recent article published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 8th February 2010, entitled: ‘Training is easy, not so the getting of wisdom‘

The article is reproduced as follows:

‘Julie Lloyd is 59. With her grey hair and warm smile she looks like a kindly grandmother. But looks can be deceiving. To the ever-alert security staff at London’s Gatwick Airport, Lloyd was a potential terrorist who brazenly tried to smuggle a gun aboard a flight from London to Toronto.

Perhaps smuggle is too strong a word. Lloyd did not try to conceal the weapon; it was in the handbag she submitted for scanning. “Gun” is also not quite accurate. It was six centimetres long and in the hands of a plastic soldier. Lloyd had bought the toy for her husband, a former army signaller. “The ‘gun’ is made of resin. It has no moving parts,” Lloyd said.

“There is no hole in the barrel, there isn’t even a trigger.”

Security staff could see this but insisted it was a “firearm” and stopped Lloyd from taking it aboard.

An airport official admitted the story sounded “incredibly stupid” but said “rules are rules and we must obey”.

I had my own little brush with “rules are rules” thinking when I visited my local health insurance office after an extended stay abroad.

I explained that I had been living in another country but had now returned home and wanted to re-activate my health insurance.

“No problem,” said the person behind the desk. “All we need is proof that you have returned to Australia.”

“Well,” I replied, “I’m sitting here right in front of you. Isn’t that sufficient?” “Not really,” she said. “We need authoritative proof.”

I offered to let her pinch me, but the lady was not for turning. Until she saw an arrival stamp in my passport, or a boarding pass, there would be no health insurance for me.

You may think these are minor irritants, risible stories that cause little harm. But sometimes rule-following can lead to serious consequences.

A couple of years ago a teenager on a hike became lost in remote bushland. Exhausted and dehydrated, he was still able to ring the emergency service from his mobile phone. He pleaded with them to send someone to rescue him. Alas, the service rules specified a particular requirement: the caller had to provide an address or at least the name of the nearest cross street.

The boy was in the bush, well off the beaten track. There were no cross-streets; in fact, no streets of any kind. Help was delayed and the boy died. He may have died anyway but hidebound adherence to a rule turned a dangerous situation into a deadly one.

At the inquest, the emergency service manager agreed the call takers had been ”fixated” with obtaining a street address but explained that this was required by their training.

The supervisor had put his finger on an old controversy in teaching: the difference between training and education, between acquiring technical skills and becoming wise.

The airport security staff who refused to distinguish a toy gun from a real one, the health insurance clerk who would not accept my corporeal presence as evidence of my return to Australia, and the emergency call centre operators who kept asking a boy lost in the bush for a street address had all been carefully trained.

They knew the protocols, understood the systems and stuck to the rules – whether they made sense or not.

We frequently hear that Australia suffers from a skills shortage: there are too few plumbers or computer scientists or doctors. To compete in the global economy, we must increase the skill level of our working population. We must spend more on education and expand our universities.

These are well-intentioned initiatives but it is not enough to train people in narrow work-related skills.

Real-world problems are rarely cut and dried; they are often ambiguous. It is impossible to have a rule for every contingency. A wise person knows how and when to improvise and when to make an exception to the rules.

Wisdom is not something you can just learn from a book or a lecture; it takes experience, reflection and self-knowledge. But even wise workers will appear hopelessly stupid if rigid rules keep them from using their judgment.

Australia needs workers who are capable of deciding the right thing to do in different situations and we need workplaces that encourage employees to use their judgment when exceptional circumstances arise.

No matter how much we invest in training, wisdom will remain the most important skill of all.’

[Source: Sydney Morning Herald, 20110207, p 11, http://www.smh.com.au/opinion/society-and-culture/training-is-easy-not-so-the-getting-of-wisdom-20110207-1ak3b.html] ..

The importance of wisdom in how humanity treats wildness and natural places (habitat)

Tasmanian forest habitat obliterated

[Photo by editor of North West Tasmanian Forests from car, 20100510, free in public domain]

.

Tasmanian forest habitat obliterated

[Photo by editor of North West Tasmanian Forests from car, 20100510, free in public domain]

.Indeed, environmental problems are rarely cut and dried; they are often ambiguous. It is impossible to have a rule for every contingency. A wise person knows how and when to improvise and when to make an exception to the rules.

Wisdom is not something you can just learn from a book or a lecture; it takes experience, reflection and self-knowledge. But even wise workers will appear hopelessly stupid if rigid rules keep them from using their judgment.

Australia’s natural environment needs workers who are capable of deciding the right thing to do in different situations and we need workplaces that encourage employees to use their judgment when exceptional circumstances arise. This applies not just to those who work in protecting our natural assets, but more importantly to those who exploit these shrinking assets and the habitats they provide to increasingly threatened wildlife.

Indeed, no matter how much we invest in training, wisdom will remain the most important skill of all.

.

Successive Australian governments’ treatment of the Australian natural environment continues to be characterised by exploitation, destruction and ambivalence that it will remain resilient forever. Such an attitude is immature and unwise in every respect.

Australian Governments need the getting of wisdom.

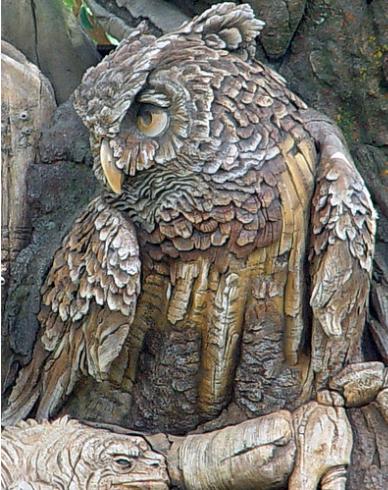

Giant Carved Owl in the Tree of Life at the Animal Kingdom, Disneyland.

Source: BeaDzyner’s photostream, http://www.flickr.com/photos/99642777@N00/379587620/

Giant Carved Owl in the Tree of Life at the Animal Kingdom, Disneyland.

Source: BeaDzyner’s photostream, http://www.flickr.com/photos/99642777@N00/379587620/

.

-end of article –