Archive for the ‘Ph03 Ecocentric Ethics’ Category

Tuesday, December 27th, 2022

The printed book’s front cover

“Over the last thirty years (Ed: 1970s – 2000s] the meaning of the word ‘wilderness‘ has changed and come under sustained attack.

How has the term become so confused? What can be done to reduce this confusion?

This book arose from the Ph.D. thesis ‘The Wilderness Knot’ (University of Western Sydney), and investigates the tangled meanings around ‘wilderness’. This ‘knot‘ is comprised of five strands; philosophical, political, cultural, justice and exploitation. ‘Wilderness‘ as a term is in a unique philosophical position, being disliked by both modernists and many postmodernists alike.

The research uses participatory action research with Aboriginal people and conservationists and wilderness journals. All scholars interviewed agreed that large natural intact areas (‘lanais‘) should be protected, though some did not call them ‘wilderness’.

Confusion declines when one can show that people hold many ideas in common. ‘Mind maps’ are used to investigate the issues and to suggest ways forward to reduce confusion. The idea of shared ‘custodianship’ or stewardship is suggested as a way forward.

This is a book for all those interested in saving and managing the Earth’s remaining large natural areas or wilderness.”

~ Haydn Grinling Washington, Ph.D (2009).

Clicking on our document hyperlink below opens to an internal Adobe PDF document stored on this website, which has been downloaded from the University of Western Sydney’s publicly available website, so it resides in the public domain.

This document is available in the public domain because that was the wishes of its author, the late Australian Environmental Scientist Haydn Grinling Washington – to share and promulgate the environmental philosophy of ‘Ecocentrism‘.

This is the opposite of prevailing ‘Anthropocentrism‘ philosophy. Human beings are NOT the central or most important entity in the universe, despite many arrogantly presuming they deserve to be.

Haydn Grinling Washington [1955-2022]

The document comprises his complete Ph.D thesis submitted in 2006.

Later in 2009, Haydn had his successful thesis published as a book entitled ‘The Wilderness Knot: Removing the confusion‘ in the form of a paperback in A4 size of some 386 pages in length, published by VDM Verlag.

The book version is currently still available to be purchased via reputable Internet resellers for a delivered price for about AUD$180. These currently include FruugoAustralia.com and Amazon.com.

This website’s editor knew Haydn from a number of meeting events (2007-2009) within the Australian conservation movement particular to the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and discussed his work and philosophies before Haydn’s untimely succumbing to bowel cancer in December 2022.

Haydn wanted to share his environmental passion for respecting the values and wonder of wilderness, native habitat and its wildlife with as many people as possible. He was not about fame and fortune from his many literary works (his prolific poetry and six books).

Our editor was invited and attended Haydn’s funeral service at The Brahma Kumaris meditation retreat centre in Leura in the Blue Mountains in Australia on Thursday 22nd December 2022. We counted about 150 attendees. It was an opportune time to catch up with seasoned conservationists, although we would have wished for a different reason. Haydn had attended this retreat on a number of occasions.

This is his Ph.D thesis in full, available to read and to download:

READ: >The Wilderness Knot (thesis by Haydn Washington Ph.D 2006 UWS) [This original 386-page PDF document is available for download free of charge, as were Haydn’s wishes].

The printed book’s back cover

Wollemi Wilderness Champion

Haydn Washington dedicated most of his adult life to selected environmental campaigns that affected him in eastern Australia about protecting wilderness areas from human harm, most notably the Wollemi wilderness in the northern part of the Blue Mountains region of New South Wales. Haydn at the time lived nearby, so was this noble planetary Nymyism beyond his backyard?

What is wrong with that? It’s such a selfless cause.

Haydn became the lead campaigner for this vast Wollemi wilderness region of 5,000 km2. He successfully saw it legally protected in 1979 as the Wollemi National Park.

The Wollemi National Park was then in 2000 officially incorporated into the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, respected as one of eight contiguous national park protected areas along with the Blue Mountains, Yengo, Nattai, Kanangra-Boyd, Gardens of Stone and Thirlmere Lakes National Parks, and the Jenolan Karst Conservation Reserve.

Tragically, two decades later from Saturday 26th October 2019 into January 2020 the custodial authority (NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service of NSW (a misnomer) in cahoots with the New South Wales Rural Fire Service) stood back and allowed a private pile-burn off Army Road near Gospers Mountain inside the Wollomi wilderness get out of control and spread over days, weeks and months.

That single ignition was allowed to blanketly incinerate the pristine Wollemi wilderness in its entirety – all 5,000 km2, endangered Koala communities and all! It was wantonly despicable neglectful act by the Wollemi NP’s and Blue Mountains World Heritage Area’s governmental custodian, NPWS.

Indeed this is why we refer to the NPWS organisation as merely the NSW Parks Service; that’s all it is useful for, just servicing parks, as in urban parks and gardens.

NPWS employs no ecologists, no botanists, no zoologists, no ornithologists, no geologists, and no environmental scientists like Haydn Washington; but only public servants.

This is despite NPWS as a state government agency being delegated with supreme responsibility for the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and all other national parks within the Australian state of New South Wales and their threatened and endangered ecosystems within.

Indeed defacto bush arson on a calamitous scale never before in Australia’s history by a anthropocentric governmental culture, having a total disregard and contempt toward Wilderness values.

Haydn would have been utterly devastated.

The entire loss of his favoured wilderness by preventable fire would have sapped him of energy and hope. He lived next to it, knew it intimately by exploration on foot and down the length of the dominant wild Colo River by paddle. One presumes the 2019 bushfire disaster of the Wollemi wilderness caused him immense grief and impacted upon his mental health.

Did wiping out the Wollemi trigger Haydn’s heath demise?

We think so. The physical cause of cancer can emerge from psychological stress.

‘Psychological stress‘ describes what individuals experience when they are under mental, physical, or emotional pressure.

‘Stressors‘ are factors that can cause stress such as negative external factors that arise outside one’s control or influence, such as the total loss of one’s life work to protect a wilderness area and its ecology as an environmental scientist with a deep passion for its ecology. Perhaps his psychological stress had become enduring and chronic, causing translating into physical harm.

Research has shown that people who experience chronic stress can have digestive problems, heart disease, high blood pressure, and a weakened immune system. People who experience chronic stress are also more prone to having headaches, sleep trouble, difficulty concentrating, depression, and anxiety and to getting viral infections. The medical science is out (unschooled) on the causation of cancer from chronic psychological stress.

But what is established is that chronic psychological stress can lead to many health problems. A 2019 meta-analysis of nine observational studies in Europe and North America also found an association between work stress and risk of lung, colorectal, and esophageal cancers. Even when stress appears to be linked to cancer risk, the relationship could be indirect. For example, people under chronic stress may develop certain unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking, overeating, becoming less active, or drinking alcohol, that are themselves associated with increased risks of some cancers. The condition may also prevent the body’s immune system from recognizing and fighting cancer cells.

Three years hence in late 2022, Haydn died of cancer, a chronic disease, at aged just 67, before his time. It is in this editor’s view that the government’s apathetic destruction of the precious Wollemi wilderness by bush arson that Haydn loved so dearly, contributed to the premature demise of his health.

NPWS Blue Mountains Branch Director David Crust had the temerity to present himself at Haydn’s funeral, appropriately donned in a full blackened suit and said nothing. The past Commissioner of the NSW Rural Fire Service, Shane Fitzsimmons who was in charge of the NSW 2019 Bushfire emergencies, including the Wollemi bushfire, did not attend.

Vale Haydn, we’re on to your noble legacy. Your passionate championing of native habitat values and your tireless campaigning fights for the preservation of Wilderness will not have been in vane on this website!

Further Reading:

[1] Vale Haydn Grinling Washington Ph.D [1955-2022], > https://habitatadvocate.com.au/vale-haydn-grinling-washington-ph-d-1955-2022/ , (NOTE: This article is a work in progress and so currently remains unavailable to access, however we expect to have it completed and accessible before the end of January 2023.)

[2] ‘ Stress and Cancer‘, National Cancer Institute, America, 202-10-21 , ^ https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/feelings/stress-fact-sheet

[3] ‘ Dr Haydn Washington’s literary works‘, > https://habitatadvocate.com.au/dr-haydn-washingtons-literary-works/

Tags: Haydn Grinling Washington, lanais, NPWS Director David Crust, NSW RFS, Nymbyism, Ph.D, RFS Commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons, The Wilderness Knot, wilderness

Posted in 04. + Ecological Jurisprudence, Ph03 Ecocentric Ethics, SAVE HABITAT FROM GOVERNMENT ARSON, Threats from Bushfire | 1 Comment »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Friday, April 14th, 2017

Ancient Balga, grass tree, xanthorroea in Dwellingup forest, South West Western Australia. Photo by Jenreflect, 20121104. Ancient Balga, grass tree, xanthorroea in Dwellingup forest, South West Western Australia. Photo by Jenreflect, 20121104.

If we can respectfully wise up and change from calling ‘Ayres Rock’ after an English mining magnate turned politician to ‘Ayers Rock/Uluru’ in 1993, then to ‘Uluru/Ayers Rock’ in 2002, then we can just drop Henry Ayres from the Rock’s association altogether. Henry Ayres was a 19th Century copper mining robber baron who devastated the landscape of Burra in South Australia. A statue in Adelaide near parliament may be appropriate.

Likewise, if we can respectfully wisen up and change from calling this grass tree a ‘black boy’ to calling it a ‘xanthorroea’ then we can call it its traditional name ‘balga’.

“We never catch marron when the creek didn’t run, or the river didn’t run. Always catch marron when the water runs. That’s our culture. You gotta give ’em a chance to breed.

And if you got anything with eggs on ’em, you threw ’em back….We never had nets, yeah, we coulda made nets but we didn’t believe that, you know, you rape the country. So you gotta leave some for the breeding.”

– Partick Hume, 2008, oral history , Kaartdijin Noongar, South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, Western Australia.

‘Aboriginal people, not environmentalists, are our best bet for protecting the planet’

by David Suzuki, published in The Vancouver Sun, 20150608, ^http://www.vancouversun.com/technology/David+Suzuki+Aboriginal+people+environmentalists+best+protecting+planet/11112668/story.html (contributed by our supporters Barbara and Stan).

<<… Using DNA to track the movement of people in the past, scientists suggest our species evolved some 150,000 years ago on the plains of Africa. That was our habitat, but unlike most other animals, we were creative and used our brains to find ways to exploit our surroundings. We were far less impressive in numbers, size, speed, strength or sensory abilities than many others sharing our territory, but it was our brains that compensated.

Over time, our numbers increased and we moved in search of more and new resources (and probably to check out the Neanderthals with whom we crossbred before they went extinct). When we moved into new territories, we were an alien creature, just like the introduced ones that trouble us today.

George Monbiot of The Guardian makes the point that we can trace the movement of our species by a wave of extinction of the big, slow-moving, dim-witted creatures that we could outwit with even the simplest of implements like clubs, pits, and spears.

Our brains were our great evolutionary advantage, conferring massive memory, curiosity, inventiveness and observational powers.

I can’t emphasize that enough.

Our brains gave us a huge advantage and it did something I think is unique — it created a concept of a future, which meant we realized we could affect that future by our actions in the present. By applying our acquired knowledge and insights, we could deliberately choose a path to avoid danger or trouble, and to exploit opportunities. I believe foresight was a huge evolutionary advantage for our species. And that’s what is so tragic today when we have all the amplified foresight of scientists and supercomputers, which have been warning us for decades that we are heading down a dangerous path, but now we allow politics and economics to override this predictive power.

No doubt after we evolved, we quickly eliminated or reduced the numbers of animals and plants for which we found uses. We had no instinctive behavioural traits to restrict or guide our actions — we learned by the consequences of what we did. And all the mistakes that we made and successes that we celebrated were important lessons in the body of accumulating knowledge of a people in a territory.

That was very powerful and critical to understanding our evolutionary success – it was painstakingly acquired experience that became a part of the culture. We are an invasive species all around the world, and I find it amazing that our brains enabled us to move into vastly different ecosystems ranging from steaming jungles to deserts, mountains to arctic tundra, and to flourish on the basis of the painful accumulation of knowledge through trial and error, mistakes, etc.

So it was the people who stayed in place as others moved on, who had to learn to live within their means, or they died. That is what I believe is the basis of indigenous knowledge that has built up over millennia and that will never be duplicated by science because it is acquired from a profoundly different basis (I wrote about the differences in a book, Wisdom of the Elders). The wave of exploration hundreds of years ago brought a very different world view to new lands — North and South America, Africa, Australia — based on a search for opportunity, resources, wealth. There was no respect for flora and fauna except as potential for riches, and certainly no respect for the indigenous people and their cultures. Of course, by outlawing language and culture of indigenous peoples, dominant colonizers attempt to stamp out the cultures which are such impediments to exploitation of the land. Tom King’s book, The Inconvenient Indian, argues very persuasively that policies are to “get those Indians off the land”.

“There was no respect for flora and fauna except as potential for riches, and certainly no respect for the indigenous people and their cultures.”

I think of my grandparents as part of the wave of exploration of the past centuries. They arrived in Canada from Japan between 1902 and 1904. When they came on a harrowing steamship trip, there were no telephones to Japan, no TV, radio, cellphones or computers. They never learned English. They came on a one-way trip to Canada for the promise of opportunity. Their children, my parents, grew up like all the other Japanese-Canadian kids at that time, with no grandparents and no elders. In other words, they had no roots in Japan or Canada. To them, land was opportunity. Work hard, fish, log, farm, mine, use the land to make money. And I believe that is the dominant ethic today and totally at odds with indigenous perspectives.

Remember when battles were fought over drilling in Hecate Strait, supertankers down the coast from Alaska, the dam at Site C, drilling for oil in ANWR, the dam to be built at Altamire in Brazil?

I was involved in small and big ways in these battles, which we thought we won 30 to 35 years ago. But as you know, they are back on the agenda today. So our victories were illusions because we didn’t change the perspective through which we saw the issues.

“Our victories were illusions because we didn’t change the perspective through which we saw the issues.”

That’s what I say environmentalists have failed to do, to use the battles to get people to change their perspectives, and that’s why I have chosen to work with First Nations because in most cases, they are fighting through the value lenses of their culture.

The challenge is to gain a perspective on our place in nature. That’s why I have made one last push to get a ball rolling on the initiative to enshrine the right to a healthy environment in our constitution. It’s a big goal, but in discussing the very idea, we have to ask, what do we mean by a healthy environment. We immediately come to the realization that the most important factor that every human being needs to live and flourish is a breath of air, a drink of water, food and the energy from photosynthesis. Without those elements, we die.

So our healthy future depends on protecting those fundamental needs, which amazingly enough, are cleansed, replenished and created by the web of life itself. So long as we continue to let the economy and political priorities shape the discussion, we will fail in our efforts to find a sustainable future. I have been trying to tell business folk and politicians that, in the battle over the Northern Gateway, what First Nations are trying to tell us is that their opposition is because there are things more important than money.>>

Things more important than Money

Noongar people are the Aboriginal traditional owners of the south-west of Western Australia and have been for over 45,000 years.

<<Noongar boodja (country) extends from north of Jurien Bay, inland to north of Moora and down to the southern coast between Bremer Bay and east of Esperance. It is defined by 14 different areas with varied geography and 14 dialectal groups.

We have a deep knowledge and respect for our country, which has been passed down by our Elders.

Noongar people have a profound physical and spiritual connection to country. It relates to our beliefs and customs regarding creation, life and death, and spirits of the earth. Spiritual connection to country guides the way we understand, navigate and use the land. It also influences our cultural practices.

For thousands of years Noongar people have resided on and had cultural connection to the booja – land. Everything in our vast landscape has meaning and purpose. We speak our own language and have our own lore and customs. The lore is characterised by a strong spiritual connection to country. This means caring for the natural environment and for places of significance. Our lore relates to ceremonies, and to rituals for hunting and gathering when food is abundant and in season. Connection to booja is passed on through our stories, art, song and dance. Noongar people not only survived European colonisation but we thrived as family groups and sought to assert our rights to our booja. For Noongar people, the south-west of Western Australia is ngulla booja – our country.

Noongar lore and custom guide the ways in which we define our country and our rights to it. Lore influences how we connect with and care for the land. As Noongar people we have a duty to speak for our country, to acknowledge its value to our communities and to observe lore that governs who may or may not ‘speak for country’.

Noongar people have always used our knowledge of the six seasons in the south-west of Western Australia to hunt, fish, and gather only the most ripe and abundant food sources for our needs.

The rituals and ceremonies performed by Noongar people over many thousands of years reflect our sustainable use of the environment and reinforce our connection to country. These rituals include domestic and social customs that observe Noongar lore governing the use of land and resources. An important and significant part of Noongar culture is the teaching of sustainable environmental practices, handed down by our Elders.

Being Noongar is to be part of a family and community, which determines our relationship to country. The relationship to country empowers our identity as a Noongar person.>>

Source: ^https://www.noongarculture.org.au/connection-to-country/

Concept of Country Concept of Country

Source: Teaching the Indigenous Concepts of Country and Sustainability (2010), by The Australian Research Institute for Environment and Sustainability (ARIES), ^http://aries.mq.edu.au/projects/deewr_indigenous_concepts/

“We come here to this place here, Minningup, the Collie River, to share the story of this area or what makes it so special. It is the resting place of the Ngangungudditj walgu, the hairy faced snake. Baalap ngany noyt is our spirit and this is where he rests. You have big bearded full moon at night time you can see him, his spirit there, his beard resting in the water. And we come to this place here today to show respect to him plus also to meet our people because when they pass away this is where we come to talk to them. Not to the cemetery where they are buried but here because their spirits are in this water. This is where all our spirits will end up here. Karla koorliny we call it. Coming home. Ngany kurt, ngany karla – our heart, our home. This, our Beeliargu, is the river people. So that’s why we always come to this Minningup. It’s very important.

This is the important part of the river, of the whole Collie River and the Preston River and the Brunswick River, because he created all them rivers and all the waters but here is the most important because this is where he rest. So whenever we come back now – my cousin died the other day so we come back here, bring his spirit home because this is where he belong here. They will bury him with his mother and you sing out to him. Ngany moort koorliny. Ngany waanginy, dadjinin waanginy kaartdijin djurip. And we come and look there and talk to you old fellow. Your people have come back. Ngany waangkaniny. I talk now. Balap kaartdijin. Listen, listen. Palanni waangkaniny. Ngany moort koorliny noonook. Ngany moort wanjanin. Your people come to rest with you now. Listen old fellow, listen for ’em, bring them home. Karla koorliny. Bring them home and then you sing to them. (Singing in language) And then chuck sand to land in the water so he can smell you. That’s our rules. Beeliargu moort. That’s the river people. That’s why this place important.”

– Joe Northover talks about Minningup Pool on the Collie River, ^https://www.noongarculture.org.au/connection-to-country/

Me, me, me anthropocentrism is so robber baron babyboomer. Learn about ecocentrism. Caring For Country starts with respect and perhaps respecting that 45,000 years of connection has shown that there are six seasons in Noongar – Birak, Bunuru, Djeran, Makuru, Djilba, Kambarang. (Ed.)

Saturday, August 17th, 2013

Eastern Water Dragon

(Physignathus lesueurii)

Taken for the benefit of the photograph, not the dragon

Photo by Editor in Blue Mountains, Australia, 20061112, photo © under ^Creative Commons]

Click image to enlarge Eastern Water Dragon

(Physignathus lesueurii)

Taken for the benefit of the photograph, not the dragon

Photo by Editor in Blue Mountains, Australia, 20061112, photo © under ^Creative Commons]

Click image to enlarge

.

Wildlife photography is not about humanising wildlife for entertainment. It ought to be about awareness, wonder and respect for wildlife and their habitat.

Zoology may be about technical understanding of the structure and classification of the animal kingdom, but since Darwin we have realised that animals are so much more complex creatures of behaviour and integral to ecology than just being taxidermied museum specimens for public display.

Zoos are just an extension of museums for the benefit of public entertainment. But they do not respect wildlife in their habitat.

[Source: ^http://katialglobal2viceduau.global2.vic.edu.au/personal-learning/]

[Source: ^http://katialglobal2viceduau.global2.vic.edu.au/personal-learning/]

.

In their habitat and ecological context, photographed wildlife may be better appreciated and valued for their integral role in Nature. But at a respectful distance.

.

Not for the camera, but naturally obscured in its habitat

A more interpretative photo, but still too close.

Photo by Editor 20061112, photo © under ^Creative Commons] Not for the camera, but naturally obscured in its habitat

A more interpretative photo, but still too close.

Photo by Editor 20061112, photo © under ^Creative Commons]

.

“The two basic processes of education are knowing and valuing”

~ Robert J. Havighurst (1900-1991).

.

.

.

Empathy for Other Species is the Key to Ethical Wildlife Photography

.

[Source: “Empathy for Other Species is the Key to Ethical Wildlife Photography”, by Jim Robertson, ^http://www.wildwatch.org/Binocular/bino01/empathy.html]

.

<< A deep admiration for Nature has led many to another level of appreciation–the craft of wildlife photography.

Unfortunately, not all who photograph wildlife do so out of caring and with respect for our fellow beings. In fact, the behavior of many photographers, both amateur and professional, can only be described as disrespectful, disruptive and sometimes dangerous to the animals they are photographing.

For example, every spring in Yellowstone you are sure to see a large group of photographers standing around–or even sitting on lawn chairs–talking loudly right outside some poor badger’s birthing den, waiting for the family to emerge. Though these folks may think nothing of the clamor of a rowdy bar or ball game, how would they like to live next door to that bar or ball field, or wake up to the racket of an expectant crowd of photojournalists right outside their bedroom window?

In response to this kind of ill-behavior, which invariably results in the harassment or endangerment of wildlife, informal guidelines have been established to spell out just how close, in yards or feet, one should get to an individual animal, depending on that species’ tolerance zone.

Badger Den

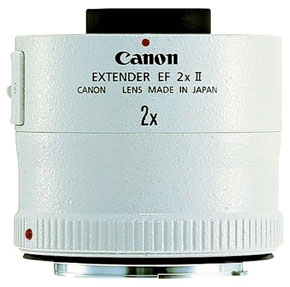

This mother and young badger were photographed across the road from their den using a 600mm telephoto lens and a 2X multiplier

Photo © Jim Robertson

^http://www.wildwatch.org/Binocular/bino01/empathy.html] Badger Den

This mother and young badger were photographed across the road from their den using a 600mm telephoto lens and a 2X multiplier

Photo © Jim Robertson

^http://www.wildwatch.org/Binocular/bino01/empathy.html]

.

But rather than memorizing numbers and gauging distances, perhaps it would be easier for photographers and wildlife observers to apply The Golden Rule in each and every situation.

However, instead of the old, oversimplified rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” why not adopt a revised golden rule that takes into account the differences between ourselves and other species? Maybe something like, “Do unto others as you think they would have you do unto them.” In other words, try to envision what the animals’ needs and self interests are and take into consideration how their lives in the wild are different from our own.

Empathy, the intellectual or emotional identification with another — or the ability to relate to others — is essential for maintaining ethical standards when photographing wildlife.

Last spring I watched from a distance as the annual gathering of noisy photographers was posted outside the entrance of a badger den. They were so deep in conversation and oblivious to their surroundings that none of them noticed as the mother badger finally made a break for it in hopes of procuring food for her young.

The day before, I had photographed the same badger den from across a road with a 600mm telephoto lens fitted with a 2X extender to bring the subject in closer without actually getting close. Because I remained on the opposite side of the road and well away from the den, quietly giving them the space they needed to engage in their activities and enjoy the sunny day, the badger and her young came and went freely, without paying me any notice.

.

The Poor Man’s Super-Telephoto Lens:

.

. .

<< The lens of choice among the serious pro wildlife photographers I know seems to be the 600mm ƒ/4 super-telephoto. It’s great for subjects that won’t let you get close, is incredibly sharp, and autofocuses quickly and accurately. However, it costs over $7,000.

That being just a bit beyond my budget, when I really need “reach,” I turn my $1,200 300mm ƒ/4 lens into a 600mm ƒ/8 by attaching a $300 2x teleconverter between the lens and camera body.Also known as tele-extenders, teleconverters are available from the major lens manufacturers for their long lenses, and offer three major benefits.

First, as just cited, they’re an economical way to get superlong focal lengths. And they’re not just for the budget-challenged. Pros use them, too—a 1.4x converter turns that monster 600mm into an 840mm; a 2x converter, into a 1200mm.

The second benefit of the teleconverter is that it doesn’t change the lens’ minimum focusing distance. Add a 2x converter to a 300mm lens that focuses down to five feet, and you have a 600mm lens that focuses down to five feet. (For comparison, my camera manufacturer’s 600mm super-telephoto won’t focus closer than 18 feet unless you attach it to an extension tube; but then it won’t focus out to infinity.)

The third teleconverter benefit is lack of bulk. A 300mm lens with a 2x teleconverter is much more compact than a 600mm ƒ/4 super-telephoto lens. (A 600mm ƒ/8 prime lens also would be smaller than the 600mm ƒ/4, but currently no one makes a 600mm ƒ/8. >>

[Source: ‘The Poor Man’s Super-Telephoto’, 20090421, by Mike Stensvold, ^http://www.outdoorphotographer.com/gear/lenses/the-poor-mans-super-telephoto.html]

.

A national Park like Yellowstone can be the perfect place for photographing animals without causing them undue stress. Since they know they are safe from hunting within park boundaries, “game species” are not so distrustful of human presence.

Although many species are easily viewable from park roadways, they are much less concerned about vehicles than people approaching on foot. Staying in your car makes wildlife feel more comfortable, and your vehicle makes a great blind for photographing animals calmly going about their business. Some of my best photos have been taken out of the window of my rig.

Other examples of photographer misconduct include trimming away vegetation–that may conceal a nest or den from people and predators–to get a clearer photo, throwing food to attract animals, and the all-too-common habit of yelling or honking at an elk, a bison or a family of bears so they will look toward the camera.

By using empathy we can begin to recognize changes in behavior and respect the signals animals use to convey to us that we are irritating them or getting too close for their comfort.

Every year irresponsible photographers are gored by bison, trampled by moose, or charged by bears. When these animals are annoyed to the point that they feel the need to defend themselves, chances are they will suffer or die for it in the end. Thoughtless conduct can also force animals to leave their familiar surroundings, interrupt natural activities necessary for survival, or even separate mothers from their young.

.

Bull Elk

This bull elk was photographed from my vehicle in Jasper National Park, Alberta, using a telephoto lens

Photo © Jim Robertson, ^http://www.wildwatch.org/Binocular/bino01/empathy.html] Bull Elk

This bull elk was photographed from my vehicle in Jasper National Park, Alberta, using a telephoto lens

Photo © Jim Robertson, ^http://www.wildwatch.org/Binocular/bino01/empathy.html]

.

Outdoor Photographer magazine ran an article in January/February 2000 on “Tips for Photographing Eagles” with the sub-heading “A long lens, the right location and a sensitive approach can get you excellent images of these majestic birds”.

The author of the article, Bill Silliker, Jr. wrote, “If you don’t have a long lens, don’t push it. Ethical wildlife photography requires that we forego attempts to photograph wildlife when we’re not equipped for it or if the attempt might harass or somehow place the subject in jeopardy. Be satisfied with images that show an eagle in its habitat. Editors use those too.”

The other day a neighbour stopped by and, upon seeing the small herd of black-tailed deer who found refuge on my land, asked if I was a hunter. When I said, “No, I’m a wildlife photographer,” he shrugged and replied, “It’s all shooting.”

Well, yes and no.

The obvious, major difference is that the animals “shot” with a camera do not end up dead. But because there are similarities to hunting, many people approach wildlife photography with a similar mind-set. It’s laughable to see photographers in a national park camouflaged from head-to-toe, sometimes including face paint, photographing a bull elk as he calmly grazes alongside the road–fully aware of their presence. And I couldn’t count how many times I’ve seen tourists run right up to a bear, elk, bison, or moose with a tiny disposable camera to get their close-up “trophy” photo.

They seem to think it’s only fair–that they are entitled to get closer–since they don’t have a large telephoto for their camera. But if they were to examine their motives they would realize that their behaviour is not fair to the animal. Is their trophy more important than the well-being of the subject of their photo?

At the height of disregard, some photographers will use hounds fitted with radio collars to pursue and corner bears, bobcats, or cougars for close-up photos of these more elusive species. If they are “lucky”, they might even catch the animal snarling in response–just the way any number of hunting magazines like to portray them on their covers or in juicy, two-page fold-outs. But how would they feel if they had to flee for their lives, chased down by a pack of dogs until they were exhausted or treed, just so someone could get a picture of them?

Wildlife photography should not be thought of as a sport or challenge against nature, or against the animals who did not volunteer for the game. Would it be considered ethical to make sport of photographing unwilling human subjects?

Unethical practices of those who photograph wildlife for self-serving purposes have given the whole field a bad name. Bill McKibben, author of “The End of Nature” has proposed a moratorium on new wildlife photos, to prevent further aggravation of endangered animals. He argues there are plenty of photos already out there for use in prints and publications. As more incidents of unethical behaviour by photographers occur, the privilege of photographing wild animals will become more and more restricted.

Still, no amount of harassment or disruption of wildlife in any way justifies the increasingly popular use of game farms by so-called wildlife photographers.

Too often, the “wild” animal seen in a publication or promotional is actually a captive animal sentenced to life on a game farm. Game farms use high fences, costing upwards of $8,000.00 per mile, to keep their preferred, sometimes exotic species in. These fences also effectively keep the native migratory wildlife out, thereby taking up valuable habitat.

While many game farms profit directly from the hunting of animals in their enclosures, others appear relatively innocuous, charging only for public viewing and private photographic sessions with “wildlife models,” including crowd-pleasing kittens, cubs, or fawns bred specifically for that purpose. But as these animals get older and less photogenic, they are auctioned off as “surplus” to the highest bidders–a common practice of zoos as well. It is likely the same animals that appeared as cute babies on calendars, greeting cards, or other publications will end up a few years later at another game farm that does profit from the canned hunting of them.

.

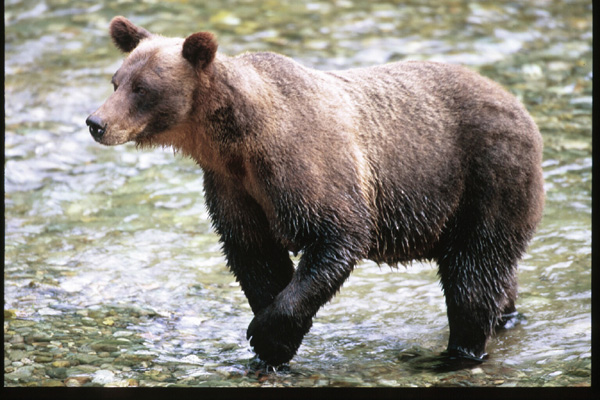

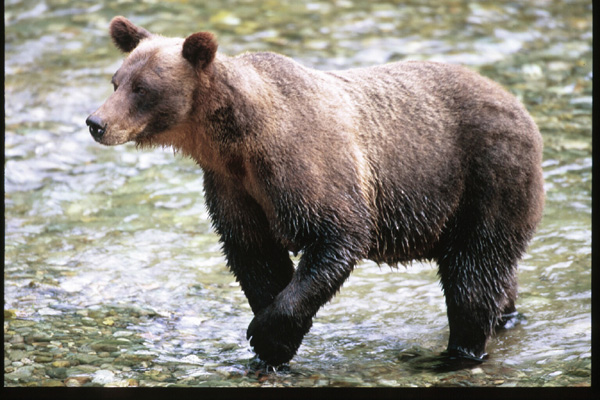

Grizzly Bear Grizzly Bear

This sow grizzly bear was photographed with a 600mm telephoto

from a supervised Forest Service observation platform along Fish Creek, in Southeast Alaska.

Photo © Jim Robertson

^http://www.wildwatch.org/Binocular/bino01/empathy.html]

.

Most photographers and photo editors do not differentiate between wild or captive animals when selling and publishing images. Using photos shot at game farms supports those who profit from exploiting animals by keeping them captive to serve as models for photographers, entertainment for tourists, or targets for trophy hunters. At the same time, these photos set a new, unnatural standard for closeness and intimacy with animals that the public expects to see in every future image.

And while on the subject of ethics, how ethical is it to top off a day of photographing waterfowl or ungulates with a dinner of poultry or red meat?

.

Don’t all living beings deserve our compassion and respect?

.

I had long heard that animals feel less threatened by someone who does not eat meat, but I wondered how long a human could survive without consuming the flesh of others. After six years as a vegan, I can attest to the fact that wild animals are not as fearful of me now, and that saying “no” to animal protein is healthier and easier than I ever would have imagined. >>

.

Sunday, December 25th, 2011

Humpback Whale in a magnificent breach

(click photo to enlarge)

^http://rtseablog.blogspot.com/2011/09/bermuda-humpback-whale-sanctuary-noaa.html Humpback Whale in a magnificent breach

(click photo to enlarge)

^http://rtseablog.blogspot.com/2011/09/bermuda-humpback-whale-sanctuary-noaa.html

.

Christmas is a time for goodwill and hope.

.

“There is joy in the companionship of others working to make a difference for future generations,” declares activist David Suzuki, “and there is hope. Each of us has the ability to act powerfully for change; together we can regain that ancient and sustaining harmony, in which human needs and the needs of all our (plant and animal) companions on the planet are held in balance with the sacred, self-renewing processes of Earth.”

.

We at The Habitat Advocate convey our goodwill and hope to those out there right now defending Nature.

We convey our goodwill and hope to the environmental activists in Tasmania’s wild defending threatened forests.

Activists of Still Wild Still Threatened (SWST) Activists of Still Wild Still Threatened (SWST)

Camp Flozza, Upper Florentine Valley

Tasmania’s Southern Forests

^http://www.stillwildstillthreatened.org/

.

SWST advocates for the immediate formal protection of Tasmania’s precious Southern Forests using a combination of political and corporate lobbying, community education, research, exploration and frontline direct action. We also promote the creation of an equitable and environmentally sustainable forest industry in Tasmania. Protecting Tasmania’s ancient forests: a real climate change solution.

.

We at The Habitat Advocate convey our goodwill and hope to the environmental activists in the Southern Ocean defending threatened whales.

Captain Paul Watson and the crew of Sea Shepherd Conservation Society (SSCS)

currently braving the freezing Southern Ocean south of Australia to defend whales from poachers.

^http://www.seashepherd.org/ Captain Paul Watson and the crew of Sea Shepherd Conservation Society (SSCS)

currently braving the freezing Southern Ocean south of Australia to defend whales from poachers.

^http://www.seashepherd.org/

.

Sea Shepherd’s mission is to end the destruction of habitat and slaughter of wildlife in the world’s oceans in order to conserve and protect ecosystems and species.

The meaning of Christmas has ancient Pagan origins pre-dating Christianity, coinciding with the Winter Solstice of the northern hemisphere celebrating the return of life at the beginning of winter’s decline. [Source: ^http://www.christmastreehistory.net/pagan]

Consistent with the original goodwill meaning of Christmas, we advocate the inclusion of Nature in this goodwill spirit:

- That each us strives to do something every day for wildness.

- That each us tries to practice simplicity and frugality. Conserve, reuse, and recycle to reduce pressures for resource extraction on remaining wildlands. Buy less. Play more.

- That each us supports conservation organizations that champion wildness, especially those acquiring acreage for wildlands preservation.

.

[Source: ^http://naturepantheist.org/ecological.html]

.

Eco-Christmas spirit

.

As environmental activist David Suzuki advocates, “each of us has the ability to act powerfully for change”. So we like the initiative of Melbourne-based company ‘Eco Christmas Trees‘. Eco Christmas Trees rents out ‘living growing trees providing the real Christmas experience without cutting down a tree‘.

Check out their website: ^http://www.ecochristmastrees.com.au/

The real Christmas experience without cutting down a tree. The real Christmas experience without cutting down a tree.

.

“What’s the use of a fine house if you haven’t got a tolerable planet to put it on?”

.

~ Henry David Thoreau, environmental activist, (1817 – 1862)]

.

Merry Yule!

.

Tags: Christmas experience without cutting down a tree, Eco Christmas Trees, Eco-Christmas spirit, goodwill to Nature, Humpback Whale, Merry Yule, Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, Still Wild Still Threatened, trees

Posted in 03. + Habitat Equality, 07 Habitat Conservation!, 31 Old Growth Conservation!, 34 Wildlife Conservation!, Ph03 Ecocentric Ethics, Ph04 Species Justice, Threats from Deforestation, Threats from Poaching and Poisoning, Whales | No Comments »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

|

|

The real Christmas experience without cutting down a tree.

The real Christmas experience without cutting down a tree.