Blue Mountains Significant Tree Register a lie

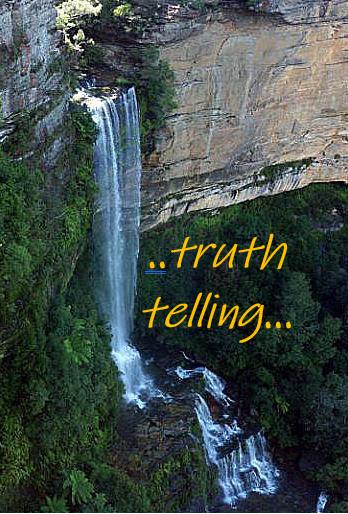

Tuesday, March 6th, 2012 One of the few remaining clusters of mature Blue Mountains Ash (Eucalytus oreades)

endemic to the Upper Blue Mountains

[They are listed on BMCC’s Significant Tree Register

..including the dozen or so killed to widen the highway]

One of the few remaining clusters of mature Blue Mountains Ash (Eucalytus oreades)

endemic to the Upper Blue Mountains

[They are listed on BMCC’s Significant Tree Register

..including the dozen or so killed to widen the highway]

.

What a steaming crock Blue Mountains Council’s (BMCC) Significant Tree Register is!

The 73 listed trees or listed tree communities on BMCC’s register listed as ‘significant‘ means exactly what? ‘BMCC significant’ is a lying euphemism for ‘big‘ and ‘expendable‘, confirmed by the fact that every time anyone wants to kill one of the listed trees, they can.

The ‘Register‘ should be renamed a ‘Remnant‘, reflecting the reducing remnancy of the Blue Mountains forests under the control of BMCC.

And many trees on the Register are indeed exotic, if not weeds. For instance, listed tree #3 is an exotic Rhododendron, #18 is an exotic cherry tree, #28 is a Radiata Pine – a listed environmental weed in another department of BMCC.

BMCC’s Significant Tree Register?

.

BMCC’s Significant Tree Register dates back to 1988, probably because of Australia’s bicentennial heritage goodwill of that year, and the likelihood of BMCC getting grant recognition for its register. That would have been a purely political froth event of no substance nor perpetuity.

‘This Development Control Plan has been prepared pursuant to Council’s resolution of 17th November, 1987 and was adopted on 21st June, 1988. The Plan encompasses the Register of Significant Trees, established in 1984. (BMCC File 7717C-4)…This Development Control Plan is to apply to all land within the boundaries of the City of the Blue Mountains.’

.

Objectives of Significant Tree Register

.

The purpose of this Development Control Plan is to:

(a) identify and protect those trees listed on the Register;

(b) promote greater public awareness of the existence of the Register, and the individual items listed;

(c) ensure existing and, importantly, prospective land owners, are made aware of the Significant Trees which may be located on their property; and

(d) ensure correct on-going care and maintenance of those trees listed, through the recommendations included with the significant tree register.’

What disingenuous lying crap!

(a) None of the listed trees is afforded any legal protection. Worse, BMCC does not raise a finger to expend effort or cost to challenge anyone wishing to kill any of the listed trees.

(b) Since 1988, BMCC has done diddly squat to promote any public awareness of either its register or any of its listed trees. Yet, BMCC certainly has killed a few of them. The last time a tree was added to the register was 1991, reflecting the three year extent of Council’s interest, memory and planning,

(c) see (a)

(d) I challenge BMCC to present any record of any “on-going care and maintenance of those trees listed”. Obviously this object clause was drafted by a naive external consultant.

.

Listed Trees – Cases in Point

.

#5 Blue Mountains Ash

(Eucalyptus oreades)

#5 Blue Mountains Ash

(Eucalyptus oreades)(Opposite 252 Old Bathurst Rd. Katoomba Opposite Lot 2 DP707, listed 6.5.84, since chainsawed)

.

#29 Smooth Barked Apple, Red Gum

(Angophora costata)

(Opposite 363 Great Western Highway, Bullaburra, opposite Lot 173, DP13407, Listed 17.7.85,

condemned by the Roads & Traffic Authority in September 2008 to widen the highway into a 4 laned Trucking Expressway)

#29 Smooth Barked Apple, Red Gum

(Angophora costata)

(Opposite 363 Great Western Highway, Bullaburra, opposite Lot 173, DP13407, Listed 17.7.85,

condemned by the Roads & Traffic Authority in September 2008 to widen the highway into a 4 laned Trucking Expressway)

.

New South Wales Government sentence imposed upon this Angophora:

.

“The Angophora (Sydney red gum) tree: the large tree is situated to the east of Boronia Road.

To retain the Angophora tree the highway would have to be widened either towards the railway line or the private properties. In both cases, land would have to be acquired, either from RailCorp or private land owners. The tree’s overhanging branches would have to be trimmed and there would be construction activities around the tree.

Arborist advice is that the consequent loss of tree roots and the pruning would instigate the decline of the tree. Angophora are highly sensitive to construction impacts such as changes to draining patterns and soil compaction. For road construction and safety reasons the tree will have to be removed.”

[Source: ‘Great Western Highway Upgrade – Community Update September 2008, ‘Bullaburra East – Ridge Street, Lawson to Genevieve Road Bullaburra, by Roads and Traffic Authority].

Ed: Well, humans can find ways of justifying anything when it suits them – ecological destruction, genocide, wars, anything. Governments and road making organisations like the RTA are collectives of people with mandates that are self-serving.

The RTA (since rebranded) does not have to widen the highway through Bullaburra. It is only doing so to encourage greater truck and car traffic and so that such road traffic can flow faster. Bigger and more roads is the mandate for this road maker. The tradition of slowing down through local towns and villages has been dismissed. Utilitarian convenience is supplanting local rights and values. Other options have been deliberately ignored such as upgrading rail freight logistics and public transport (the rail runs adjacent to and follows the same route as this highway). Land acquistion is an easy process for the RTA. It’s management is just choosing not to take this option because it sees no value in the tree nor in Bullaburra’s amenity.

The tree’s overhanging branches would not have to be trimmed and construction activities could be well away from the tree, if the RTA management so choosed.

The RTA’s standard justification “safety reasons” had to be the clincher. the RTA relies on the ‘safety justification’ as its fallback to get its way, because it has convinced that no-one can reasonably challenge such a justification. That the M4 Motorway with its six lanes has become one of the most deadly RTA roads in New South Wales does not seem to trouble the RTA sufficiently to invest in making the M4 safer. The RTA is hypocritical about road safety.

The value of encouraging faster and bigger trucks and more cars to race through Bullaburra at 80+kph is more important to it than conserving some tree. That this particular tree has been dated by a specialist arborist as being older than300 years and so would have stood when the Three Explorers first crossed the Blue Mountains in 1813, is dismissed as worthless by the RTA and the New South Wales Government. Labor and Liberal are no different in this world view of ‘progress’. Bullaburra is set to be transformed into a Blaxland with bigger trucks racing through it. Bullaburra will become even more divided that what it is now.

If this tree were a war cemetery, there is no question that the cemetery value would be respected and a trucking expressway would not be carved through it.

.

Les Wielinga

NSW Roads and Traffic Authority Chief (2006-2012)

Executioner of Bullaburra’s Angophora

and Strategic Planner of the Trucking Expressway juggernaut through the Blue Mountains

Les Wielinga

NSW Roads and Traffic Authority Chief (2006-2012)

Executioner of Bullaburra’s Angophora

and Strategic Planner of the Trucking Expressway juggernaut through the Blue Mountains

.

#33 Scribbly Gum

(Eucalyptus sclerophylla/Eucalyptus piperita hybrid)

(Cnr St Georges Cres. & Adeline St. Faulconbridge, Lot 5 DP8526 , Listed 24.8.85,

condemned in Sep 2011 for selfish dual occupancy housing development)

#33 Scribbly Gum

(Eucalyptus sclerophylla/Eucalyptus piperita hybrid)

(Cnr St Georges Cres. & Adeline St. Faulconbridge, Lot 5 DP8526 , Listed 24.8.85,

condemned in Sep 2011 for selfish dual occupancy housing development)

.

Blue Mountains Council arborist has condemned the tree as having ‘extensive decay’.

.

Trial by Ordeal?

.

Local residents protesting to save the tree, believe this native Scribbly Gum to be quite healthy and that the arborist’s so-called ‘decay‘ is in fact a natural fungus. The residents believe that Council’s arborist’s assessment has incorrectly condemned the tree and that only after the tree trunk is chainsawed will the proof of the tree’s health be revealed.

It will be akin to being a Medieval Trial by Ordeal imposed on those suspected of being a witch. An example is where a priest would demand a suspect to place his hand in the boiling water. If after three days, God had not healed his wounds, the suspect was guilty of the crime.

In the case of this Scribbly Gum, if after chainsawing it, the trunk shows no signs of internal decay, then it can be confirmed as having being healthy, but by then it will be dead.

.

The Council’s assessment:

“It should also be noted that the significant tree has been assessed as not being viable for retention in any case as the result of extensive decay throughout the trunk. This matter is discussed in more detail in the body of the report.”

[Source: Blue Mountain Council, Business Paper, Using Land for Living Item 20, Ordinary Meeting, 20110628, Development Application No. X/443/2010 for a detached dual occupancyconsisting of a singe storey dwelling and a two storey dwelling on Lot 5 SEC. 2 DP 8526, 47 St Georges Crescent, Faulconbridge, File No: F06738 – X/443/2010 – 11/85977, Clause 44, p.214].

#61 Blue Mountains Ash

#61 Blue Mountains Ash(Eucalyptus oreades – once was a ridgetop forest)

(Railway Reserve opposite Katoomba Hospital, Listed 6.11.89, half the trees chainsawed in 2008 to widen the highway into a Trucking Expressway. What’s left is a token coppice so that the RTA can claim on paper that it respected the ‘significant’ status.)

.

Relevance and future of the Significant Tree Register

.

In November 2011, Blue Mountains Councillor Janet Mays presented a Notice of Motion to Council:

.

“That the Council receives a report detailing the role and relevance of Council’s Significant Tree Register, including the cost of both managing and maintaining that Register.”

Background

The recent decision by the Land & Environment Court, to uphold an appeal by the applicants at 47 St Georges Crescent, Faulconbridge, includes permission to remove a tree that is listed on Council’s Significant Tree Register that decision brings into question the relevance of this Register.

The report should outline the role and relevance of the Register in providing decision-making capability to Council’s Planning Officers. The role and relevance of the Register should then be considered in terms of benefits and cost of maintaining this Register. Dependant on the benefits and the costs, the future utility of the Register should also be discussed.”

[Source: Blue Mountains Council, Business Paper, Notices of Motion, Item 26, Ordinary Meeting, 20111122, Subject: Council’s Significant Tree Register, File No: F06745 – 11/178956, p.173] .Ed: Meanwhile, anthropocentric prejudice sees the National Trust of Australia (an organisation supposedly committed to promoting and conserving Australia’s indigenous, natural and historic heritage) recognise people as ‘National Living Treasures’. No thought is given to Australian native trees, many which have stood longer than any colonist set foot on Australian soil. Surely, a 300+ year old native tree has more claim to being a national living treasure.

On 4 March 2012, two days ago, we hear that Queensland mining magnate Clive Palmer has been named a National Living Treasure. Palmer has made is fortune exploiting Australia’s landscape for his personal gain. Clearly, Australian Governments continued to be dominated by 20th Century Baby Boomer exploitative world views.

.

Further Reading

.

[1] Blue Mountains Council Register of Significant Trees (1988), ^http://www.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/download.cfm?f=28AD1E14-423B-CE58-AD64F47560FC3345, [Read Register]