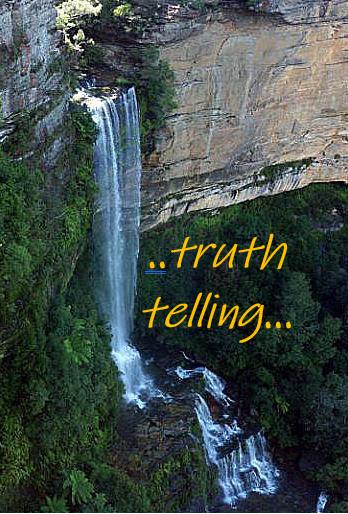

Ecotourism branding lies

Wednesday, July 24th, 2013 Jaguars fight – set up to entertain “ecotourists”

‘Reality Zoos’ ?

[Source: ^http://www.ironammonite.com/2011/11/ecotourism-or-ecoterrorism-big-cats.html]

Jaguars fight – set up to entertain “ecotourists”

‘Reality Zoos’ ?

[Source: ^http://www.ironammonite.com/2011/11/ecotourism-or-ecoterrorism-big-cats.html]

.

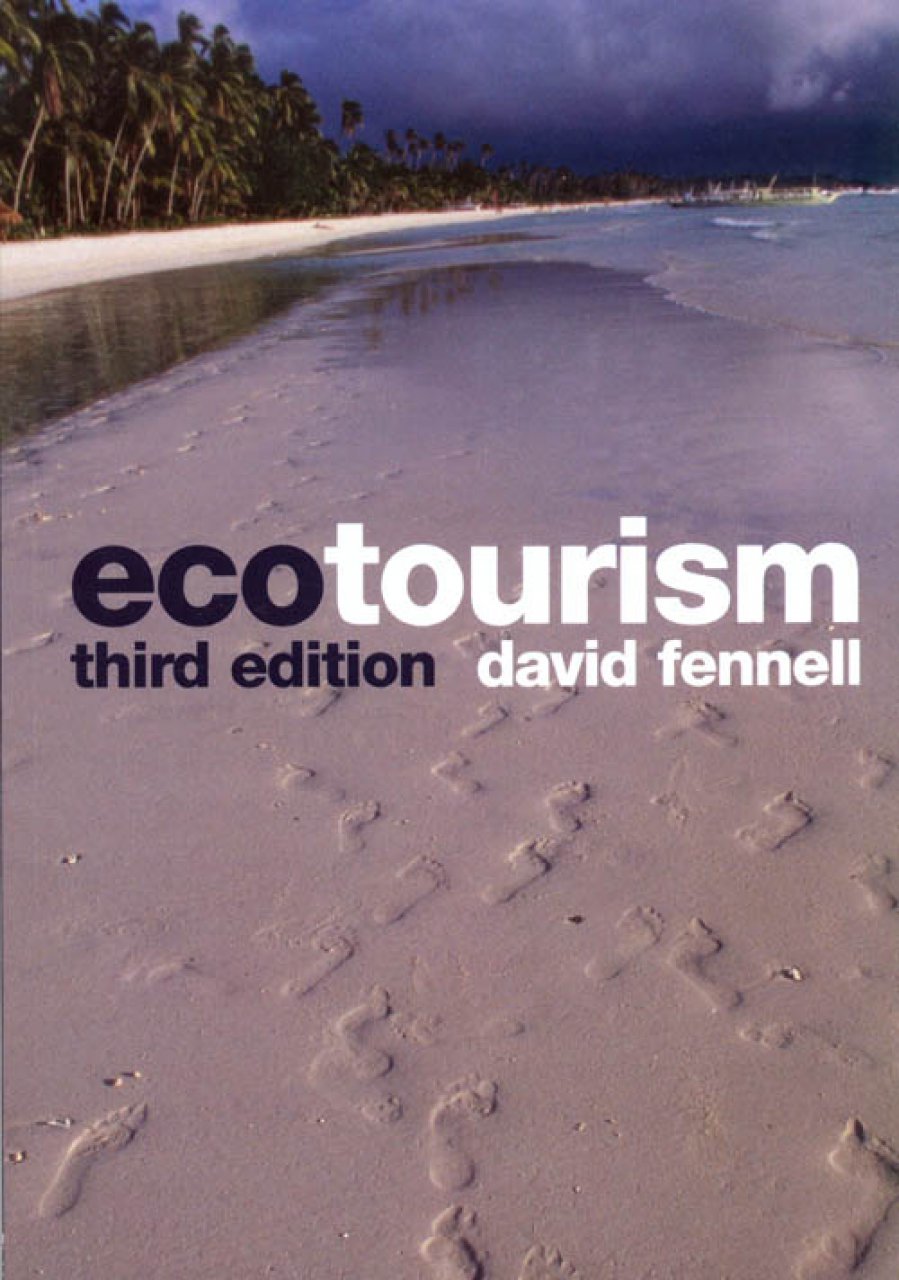

In 1999, Canadian David A. Fennell, PhD, based at Brock University in Ontario in the Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies wrote a poignant text about the ‘ecotourism’ phenomenon. We recommend its read, now in its third edition from 2007. We extract a small portion from the second edition as an article below.

[Text: ‘Ecotourism: an introduction’, 2003, 3e, book by David A. Fennell, published by Routledge (imprint of Taylor and Francis Group), New York, America, ISBN 0-415-30365-6, Dewey Code: 338.4791-dc21]

Third Edition (2007)

^http://www.nhbs.com/ecotourism_tefno_87800.html

Third Edition (2007)

^http://www.nhbs.com/ecotourism_tefno_87800.html

.

<< As arguably the largest and fastest growing industry, the potential impacts of tourism are considerable.

Devised by social and natural scientists, ‘ecotourism‘ can be an effective way to safeguard local communities and prevent the destruction of the natural world.

Responding to increased interest and global competition, the tourist industry has not been slow to appropriate the term to describe a host of different experiences, maredly different from its origins. (Fennell identifies) “inconsistencies in the philosophical basis of ecotourism, and the development and implementation of ecotourism products in a variety of destinations.

For example, in a sobering account of her travel experience in the Peruvian rainforest, Arlen (1995) writes that ecotourism has reached a critical juncture in its evolution. She speaks graphically of instances where tourists endured swimming in water with human waste; guides capturing Sloths and Caiman for tourists to photograph; raw sewage openly dumped into the ocean; mother Cheetahs killing their cubs to avoid the harassment of Cheetah-chasing tourists; and an ecotourism industry under-regulated with little hope for enforcement.

Similar experiences have been recorded by other writers including Farquharson (1992), who argues that ecotourism is a dream that has been severely diluted. She writes that whereas birding once prevailed, ecotourism has fallen into the clutches of many of the mega-resorts like Cancún: the word (ecotourism) changes colour like a chameleon.

.

Cancún Over-tourism

.

Cancún Over-tourism

.

What began as a concept designed by ecologists to actively prevent the destruction of the environment has become a marketing term for tourism developers who want to publicise clean beaches, fish-filled seas and a bit of culture for when the sun begins to hurt (Farquharson (1992: 8).

.

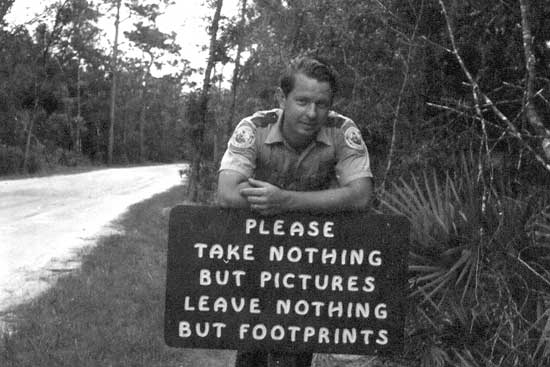

Florida State Park Ranger Randy Brown

Florida State Park Ranger Randy Brown

.

These scenarios appear to be worlds apart from the evolution of ecotourism in the not too distant past, where, as outlined by Farquharson, it was seen as a haven for birdwatchers and scientists alike.

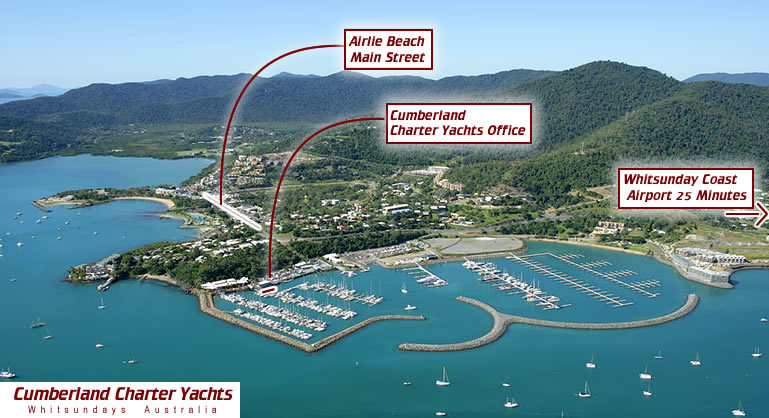

Whitsundays – original

Whitsundays – original (North Queensland)

.

Clearly, ecotourism is a thriving economic enterprise in both developed and the less developed countries around the world. However, while scientists occupy one end of the ecotourism continuum, in other cases this form of tourism has come to represent a completely different type of experience, with the industry clamouring to take advantage of a larger softer market of ecotourists, as a result of increased interest and competition.

. Whitsundays – since exploited

Whitsundays – since exploited

.

According to some (Budowski in Arlen, 1995) ecotravellers at this softer end of the continuum have learned to expect a type of experience much like what one might get in Hawaii or Cancún. The industry involvement is just one of the many facets of the ecotourism industry discussed in (Fennell’s) book. Others include government involvement in ecotourism, aboriginal interests, partnership and training, tourism demand, structural differences between developed and developing countries, policy and regulation, ethics and responsibility, and so on. >> (extracted from Fennells’ Preface)

.

Lessons from 20th Century Mass Tourism

.

<<..Tourism has been both lauded and denounced for its ability to develop and therefore transform regions into completely different settings. In the former case, tourism is seen to have provided the impetus for appropriate long-term development; in the latter the ecological and sociological disturbance to transform regions can be overwhelming. While most of the documented cases of the negative impacts of tourism are in the developing world, the developed world is certainly not an exception.

Young (1983), for example, documented the transformation of a small fishing farming community in Malta by graphically illustrating the extent to which tourism development – through an increasingly complex system of transportation, resort development, and social behaviour – overwhelms such areas over time.

These days we are more prone to vilify or characterise conventional mass tourism as a beast, a monstrosity which has few redeeming qualities for the destination region, their people and their natural resource base.

Consequently, mass tourism has been criticised for the fact that it dominates tourism within a region owing to its non-local orientation, and the fact that verry little money is spent within the destination actually stays and generates more income.

It is quite often the hotel or mega-resort that is the symbol of mass tourism’s domination of a region, which are often created using non-local products, have little requirement for local food products, and are owned by metropolitan interests. Hotel marketing occurs on the basis of high volume, attracting as many people as possible, often over seasonal periods of time. The implications of this seasonality are such that local people are at times moved in and out of paid positions that are based solely on this volume of tourist traffic. Development exists as a means by which to concentrate people in very high densities, displacing local people from traditional subsistence-style livelihoods (as outlined by Young 1983) to ones that are subservience based.

Finally, the attractions that lie in and around these massive developments are created and transformed to meet the expectations and demands of visitors.

Emphasis is often on commercialisation of natural and cultural resources, and the result is a contrived and inauthentic representation of, for example, a cultural theme or event that has been eroded into a distant memory. >> (extracted Fennell’s page 4)

.

.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘The Changing World of Bali Religion Society and Tourism’ , 2005, by Leo Howe, published by Routledge, Britain, ^http://antropologias.descentro.org/files/downloads/2012/03/The_Changing_World_of_Bali__Religion__Society_and_Tourism.pdf

>The Changing World of Bali Religion Society and Tourism (177 pages, 2.5MB, PDF)

.

[2] ‘Is ecotourism good for the environment and world?’, 2010, Campbell College, Belfast, Northern Ireland, ^http://www.campbellcollege.co.uk/academic/departments/geography/Documents/ecotourism.pdf

>Is ecotourism good for the environment and world? (4 pages, 56kb, PDF)

.

[3] ‘ The Place of Ecotourism, with particular reference to Australia’, 2001, by Associate Professor Robyn Bushell, Head of Tourism Studies, School of Environmental & Agriculture

University of Western Sydney, Australia, ^http://hsc.csu.edu.au/geography/activity/local/tourism/HECOTOUR.pdf