Antarctic ecology threatened by fishing

Sunday, October 21st, 2012 Snow Petrel (Pagodroma nivea) over Antarctic Ice

(Photo by John Weller)

Snow Petrel (Pagodroma nivea) over Antarctic Ice

(Photo by John Weller)

.

‘An alliance of 30 global environment organisations today launched a report calling for greater protection for the East Antarctic marine environment, on the eve of an international meeting where the future conservation of this region will be decided.

The Antarctic Ocean Alliance (AOA) report “Antarctic Ocean Legacy: Protection for the East Antarctic Coastal Region”, supports a proposal from Australia, France and the EU for East Antarctic marine protection but also calls for additional important areas to be included such as the Prydz Gyre, the Cosmonaut Polynya, and the East India seamounts.

In just four days, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), will begin meetings in Hobart, Tasmania to debate several proposals for marine protection, including the East Antarctic coastal region and the Ross Sea. The Ross Sea was the subject of an AOA report in February this year.

“The AOA is calling on CCAMLR Members to support the current East Antarctic coastal region proposal put forward by Australia, France and the EU, but to also consider additional areas in subsequent years that our report shows are critical to ensuring the wildlife in the region gets the protection it needs,” said AOA Director Steve Campbell.

“We are calling on CCAMLR Members to support the establishment of the world’s largest network of marine reserves and Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in Southern Ocean as a legacy for future generations,” Mr. Campbell said. “Decisive protection for the East Antarctic coastal region and Ross Sea would be a great start to that process.”

The remote East Antarctic coastal region is home to a significant number of the Southern Ocean’s penguins, seals and whales. It also contains rare and unusual seafloor and oceanographic features, which support high biodiversity.

Adelie Penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae) in Antarctica

(Photo by John Weller)

Adelie Penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae) in Antarctica

(Photo by John Weller)

.

“While the AOA supports the conservation gains included in the proposal from Australia, France and the EU, we hope that CCAMLR delegates will consider expanding on the area to be protected to include additional areas that are critical habitats for Adélie penguins, Antarctic toothfish, minke whales and Antarctic krill in the future,” said Mr. Campbell.

Antarctic marine ecosystems are under increasing pressure. Growing demand for seafood means greater interest in the Southern Ocean’s resources, while climate change is affecting the abundance of important food sources for penguins, whales, seals and birds.

In October 2011, the Antarctic Ocean Alliance proposed the creation of a network of marine protected areas (MPAs) and marine reserves in 19 specific areas in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica.

This report, ‘Antarctic Ocean Legacy: Protection for the East Antarctic Coastal Region‘, outlines a vision for marine protection in the East Antarctic, one of the key regions previously identified by the AOA.

Currently, only approximately 1% of the world’s oceans are protected from human interference, yet international agreements on marine protection suggest that this number should be far higher.

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), the body that manages the marine living resources of the Southern Ocean (with the exception of whales and seals), has set a target date of 2012 for establishing the initial areas in a network of Antarctic MPAs.

One of the key places for which the AOA seeks protection is the East Antarctic coastal region. This remote area, while vastly understudied, is home to a significant proportion of the Southern Ocean’s penguins, seals and whales. The East Antarctic coastal region also contains large seafloor and oceanographic features found nowhere else on the planet. The AOA offers this report to assist in designating marine reserves and MPAs in the East Antarctic coastal region. This is the third in a series of “Antarctic Ocean Legacy” proposals from the AOA.

This report describes the geography, oceanography and ecology of this area. The AOA acknowledges the scientists and governments that have studied the region and welcomes and gives support to the proposal that has been submitted for marine protection in the East Antarctic by Australia, France and the EU, but is cautious that constant vigilance and additional marine reserves will be required to ensure that the conservation values of the proposal are not compromised in the future.

Killer Whales breaching in Antarctic waters

(Photo by John Weller)

Killer Whales breaching in Antarctic waters

(Photo by John Weller)

.

The AOA proposes that in addition to the seven areas referenced by Australia, France and the EU, four additional areas also be considered for protection in the coming years. A network MPAs and marine reserves encompassing these additional areas and those proposed by Australia, France and the EU would span approximately 2,550,000 square kilometres.

Because the East Antarctic coastal region is “data‐poor”, the AOA plan is based on the application of the precautionary approach, one of the core concepts at the centre of CCAMLR’s mandate.

This proposal includes:

- A representative sample of biological features at the species, habitat and ecosystem scale to ensure broad scale protection.

- Areas of protection large enough to encompass broad foraging areas for whales, seals, penguins and other seabirds.

- Protection of many of the region’s polynyas, which are sources of food for many species.

- Protection of unique geomorphic features, including the Gunnerus Ridge, Bruce Rise, a trough mouth fan off Prydz Bay, various seamounts and representative areas of shelf, slope and abyssal ecoregions.

- Full protection of Prydz Bay, an area that supports large numbers of seabirds and mammals as well as likely nursery grounds for krill and toothfish.

- Protecting areas of scientific importance that may serve as climate reference areas.

.

Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii) in Antarctic waters

(Photo by John Weller)

Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii) in Antarctic waters

(Photo by John Weller)

.

Currently only 1% of the world’s oceans are protected from human interference, yet international agreements on marine protection suggest that this number should be far higher.

The designation of a network of large‐scale MPAs and marine reserves in the East Antarctic coastal region would be an important and inspirational step for marine protection in the Southern Ocean. CCAMLR Members have an unprecedented opportunity to establish a network of marine reserves and MPAs an order of magnitude greater than anything accomplished before. With such a network in place, key Southern Ocean habitats and wildlife, including those unique to the East Antarctic coastal region, would be protected from the impacts of human activities.

The AOA submits that with visionary political leadership, CCAMLR can grasp this opportunity and take meaningful steps to protect critical elements of the world’s oceans that are essential for the lasting health of the planet.

.

Notes:

.

- The AOA’s research has identified over 40% of the Southern Ocean that warrants protection in a network of large-scale marine reserves and MPAs, based on the combination of existing marine protected areas, areas identified within previous conservation and planning analyses and including additional key environmental habitats described in the AOA’s report.

- The AOA is campaigning for CCAMLR to adopt its ‘Vision for Circumpolar Protection’ while this unique marine environment is still largely intact. CCAMLR has agreed to create a network of marine protected areas in some of the ocean around Antarctica this year but the size and scale is still under debate.

- CCAMLR is a consensus body that meets with limited public participation and does not provide media access. The AOA believes that, without public attention during the process, only minimal protection will be achieved. It has launched the ‘Join the Watch’ campaign focused on CCAMLR, which now has more than 100,000 participants from around the world.

- Antarctic waters make up almost 10% of the world’s seas and are some of the most intact environments left on earth. They are home to almost 10,000 unique and diverse species such as penguins, seals and whales.’

.

[Sources: ‘New AOA report calls for protection of critical East Antarctic marine habitats’, by Blair Palese, AOA Communications Director, 20121019 ^http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php?/weblog/article/New-AOA-report-calls-for-protection-of-critical-East-Antarctic/, ‘Antarctic Ocean Legacy: Protection for the East Antarctic Coastal Region’, by Antarctic Ocean Alliance, 20121018, ^http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php?/pr-article/antarctic-ocean-legacy-protection-for-the-east-antarctic-coastal-region/].

.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] East Antarctica targeted by dodgy fishing

.

Read Report: >’Antarctic Ocean Legacy: Protection for the East Antarctic Coastal Region.pdf (1.6MB), 2012, by the Antarctic Ocean Alliance (AOA), ^http://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/11352_aoa_east_antarctic_report_web__2_.pdf]

.

[2] Antarctic Toothfish?

.

Antarctic Toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) the Ross Sea, Antarctica

[Source: The Last Ocean, photo by Rob Robbins, ^http://lastocean.wordpress.com/]

Antarctic Toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) the Ross Sea, Antarctica

[Source: The Last Ocean, photo by Rob Robbins, ^http://lastocean.wordpress.com/]

.

‘Antarctic Toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) are by far the dominant fish predator in the Ross Sea. Whereas most Antarctic fish species rarely get larger than 60 cm, Ross Sea toothfish can grow in excess of two metres in length and more than 150 kg in mass.

Being top predators, they feed on a variety of fish and squid, but they are also important prey for Weddell seals, sperm whales, colossal squid, and a specific type of killer whale that feeds almost exclusively on toothfish.

While these fish have long been studied for their ability to produce anti-freeze proteins that keep their blood from crystallizing, very little is known about their life cycle and distribution. We do know they live to almost 50 years of age and grow relatively slowly. They likely mature between 13 and 17 years of age (120-133 cm in length).

In the Ross Sea, toothfish are caught throughout the water column from about 300 metres to more than 2,200 metres deep. While most fish control their buoyancy with a swim bladder, toothfish actually use lipids or fats (lending to their popularity as a food fish).

Recent research suggests that toothfish have a complex life cycle which includes a remarkable spawning migration. In the Ross Sea region, adults feed over the continental shelf and slope, and then migrate from the Ross Sea continental shelf to northern seamounts, banks and ridges around the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge system. Here in the northern offshore waters, fish release their eggs, which are then picked up by the Ross Gyre and brought back to the shelf. This hypothesis is likely, but not yet proven because Antarctic toothfish eggs or larvae have never been found. Small juveniles have been found in other regions, but never in the Ross Sea, lending even more mystery to the life cycle of this fish.’

.

[Source: The Last Ocean, ^http://www.lastocean.org/Commercial-Fishing/About-Toothfish-/All-about-Antarctic-toothfish__I.2445].

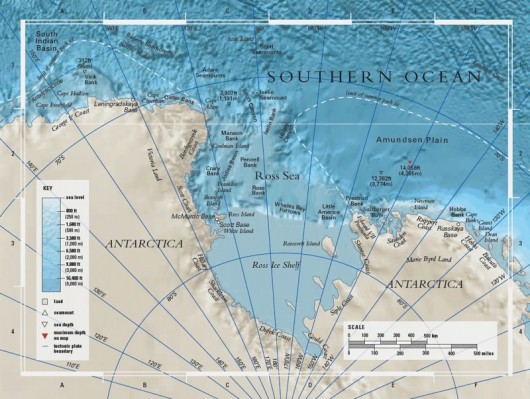

[3] Antarctica’s ‘Ross Sea’?

.

The Ross Sea ecosystem is the last intact marine ecosystem left on Earth. Unlike many other areas of the world’s oceans, the Ross Sea’s top predators are still abundant. Here they drive the system, shaping the food web below in a way that’s totally unique.

While comprising just two percent of the Southern Ocean, the Ross Sea is the most productive stretch of Antarctic waters. It has the richest diversity of Southern Ocean fishes, an incredible array of benthic invertebrates and massive populations of mammals and seabirds.

More than a third of all Adélie penguins make their home here, as well as almost a third of the world’s Antarctic petrels and Emperor penguins. Also found here are Antarctic Minke whales, Weddell and Leopard seals, and Orcas, including a population specially adapted to feed on Antarctic toothfish, the top fish predator of the Ross Sea.

The Ross Sea Map

Source: ^http://oceana.org/en/explore/marine-places/ross-sea

The Ross Sea Map

Source: ^http://oceana.org/en/explore/marine-places/ross-sea

.

The Ross Sea’s rich biodiversity and productivity puts it on a par with many World Heritage sites, like the Galapagos Islands, African Rift lakes and Russia’s Lake Baikal.’

.

[Source: The Last Ocean, ^http://www.lastocean.org/Ross-Sea/The-Ecosystem-/Toothfish-Adelie-penguins-Antarctic-Petrels-Minke-whales__I.273].

[4] Ross Sea dodgy fishing escapades

.

Dec 2011: Dodgy Russian-flagged fishing rust-bucket ‘Sparta’

hits an iceberg while fishing in Antarctica’s Ross Sea – a long way from Russia

Dec 2011: Dodgy Russian-flagged fishing rust-bucket ‘Sparta’

hits an iceberg while fishing in Antarctica’s Ross Sea – a long way from Russia[Source: ^http://www.stuff.co.nz/taranaki-daily-news/news/national/6150088/Distress-call-sparks-Southern-Ocean-rescue-effort]

.

Jan 2012: Dodgy Korean-flagged rust bucket fishing vessel ‘Jeong Woo 2’

burns while fishing in Antarctica’s Ross Sea

– a long way from Korea

Jan 2012: Dodgy Korean-flagged rust bucket fishing vessel ‘Jeong Woo 2’

burns while fishing in Antarctica’s Ross Sea

– a long way from KoreaAustralian records show the Jung Woo 2 is owned by the Sunwoo Corporation and is licensed to fish for Chilean sea bass, crab and other bottom-dwelling fish. The old ship was built in Japan in 1985 and is registered in Busan, South Korea. [Source: ^http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jan/11/three-fishermen-killed-blaze-antarctica]

.

[5] Mar 2012: ‘US retailer says no to ‘Ross Sea’ seafood’

.

‘A third US retailer has announced it will not stock seafood from Antartica’s Ross Sea for environmental reasons, reports Greenpeace.

Harris Teeter joins US supermarket chains Safeway and Wegmans by taking the ‘Ross Sea Pledge’ which means it will not buy or sell seafood from that area. It is also calling for the entire Ross Sea to be protected.

“We have pledged not to buy or sell any seafood harvested from the Ross Sea,” the company states on its website. “By taking the “Ross Sea Pledge,” we encourage the nations who are members of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources to designate the entire Ross Sea as an MPA [Marine Protected Area],” it continues.

The Ross Sea has been identified as the least human affected large oceanic ecosystem remaining on Earth. Many Scientists are advocating for it to be designated as a fully protected marine reserve. However, a longline fishery for Antarctic toothfish, started by New Zealand vessels in the late 1990s, is operating in the Ross Sea and supplying the luxury market.

“The delicate balance of the fragile Ross Sea is under threat from commercial fishing,” says Greenpeace New Zealand Oceans Campaigner Karli Thomas.

“Although technology has made it possible, it is simply not sustainable to be fishing every last corner of our ocean. The Ross Sea is a special place that we should be protecting as the home to diverse and unique wildlife, and a refuge in the face of climate change – not exploiting to feed the wealthy.”

In 2010, Greenpeace published a report outlining the role that seafood traders, retailers and chefs can play in protecting the Ross Sea. “The announcement by Harris Teeter shows there is a growing awareness by retailers that the Ross Sea should be protected as no-go area,” says Thomas.

The recently formed Antarctic Ocean Alliance, a group of environmental organisations, last week launched a report calling for a large-scale marine reserve to be established in the Ross Sea.’

.

[Source: Greenpeace, ^http://www.greenpeace.org/new-zealand/en/press/US-retailer-says-no-to-Ross-Sea-seafood/].

[6] Carting Away the Oceans…

.

Read Report: >’Carting Away the Oceans V.pdf‘, by Casson Trenor, Greanpeace USA 2011, ^http://www.greenpeace.org/usa/Global/usa/planet3/publications/oceans/CATO_V_FINAL.pdf, 2MB]

.

[7] Indiscriminate illegal gillnetting

.

Illustration of a bottom gill net

Illustration of a bottom gill net(Michigan Sea Grant)

.

Significant progress has been made in reducing the level of IUU catch through the cooperation of CCAMLR, its Member nations and legal fishers. However, a number of IUU fishers still operate primarily in the South Indian Ocean and directly off the East Antarctic coastal region.

The conservative catch limits remain in place today, as IUU fishing remains a problem and is unlikely to further decline. In recent years, IUU fishers have increasingly used deepwater gillnets in the area, making IUU estimates nearly impossible to calculate.

Gillnets are banned by CCAMLR because they pose a significant environmental threat due to their high levels of bycatch and the risk of “ghost fishing,” which refers to nets that have been cut loose or lost in the ocean and continue catching marine life for years.

The amount of toothfish caught in IUU gillnets remains unknown, but is likely substantial. For example, gillnets found by Australian officials in 2009 spanned 130 km and had ensnared 29 tonnes of Antarctic toothfish.

IUU fishing and the uncertainty associated with toothfish populations severely compromise fisheries management and has led to the rapid decline of some toothfish stocks.

Moreover, like many deep dwelling fish, toothfish live a long time, grow slowly as adults and mature late in life, all characteristics that make them vulnerable to overfishing.

Local depletions of toothfish may easily occur, as has happened over BANZARE Bank. Scientists have yet to understand the Antarctic toothfish’s life history in the East Antarctic, which further compromises management.’

.

[Source: Antarctic Ocean Alliance (AOA) report “Antarctic Ocean Legacy: Protection for the East Antarctic Coastal Region”, page 19].

[8] Illegal Unreported Unregulated (IUU) Fishing’

.

In a 1999 report to the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, the UN Secretary General stated that IUU fishing was “one of the most severe problems currently affecting world fisheries.”

By hindering attempts to regulate an otherwise legitimate industry, IUU fishing puts at risk millions of dollars of investment and thousands of jobs as valuable fish resources are wantonly depleted below sustainable levels. Disregard for the environment by way of high seabird mortality and abandonment of fishing gear gives rise to even more concern, as does the general disregard for crew safety on IUU boats.

IUU fishing on the high seas is a highly organised, mobile and elusive activity undermining the efforts of responsible countries to sustainably manage their fish resources. International cooperation is vital to effectively combat this serious problem. By using regional fisheries management organisations as a vehicle for cooperation, fishing states, both flag and port states, and all major market states, should be able to coordinate actions to effectively deal with IUU fishing activity.

At the initiative of the United Nations FAO Committee on Fisheries, States developed the Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing. It is the first global legally-binding instrument that aims to reduce the occurrence of IUU fishing. Australia signed the Agreement on 27 April 2010 and intends to take binding treaty action to ratify these amendments.

IUU fishing is jeopardising the Australian harvest of fish stocks both within and beyond the Australian Fishing Zone (AFZ), and the long-term survival of fishing industries and communities. The recent incidence of illegal fishing of Patagonian toothfish in Australia’s remote Southern Ocean territories is a prime example of the damaging effects of unregulated fishing on the sustainability of stocks and the viability of the Australian industry.

Australia’s remote sub-Antarctic territories of Heard and the McDonald Islands lie in the southern Indian Ocean about 4,000 km south-west of Perth. Since 1997, six vessels have been apprehended by Australian authorities for illegal fishing in the AFZ around Heard Island and the McDonald Islands in the sub-Antarctic.

Illegal fishing also occurs in Australia’s northern waters and is largely undertaken by traditional or small-scale Indonesian vessels.

Since 1974, traditional Indonesian vessels have been allowed access to a defined area of the Australian fishing zone (north west of Broome) in which Australia agrees not to enforce its fisheries laws – an area known as the MoU Box. IUU fishing by Indonesian vessels has occurred both in the MoU Box (through a failure to comply with agreed rules) and as a result of opportunistic fishing in other areas of the AFZ around the MoU Box.

In more recent times, there has been a noticeable shift away from what could be termed ‘traditional’ fishing. Vessels are being found further east, as far across as the Torres Strait, and are largely targeting shark for its valuable fin.’

.

[Source: ‘Overview: illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing‘, Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, ^http://www.daff.gov.au/fisheries/iuu/overview_illegal,_unreported_and_unregulated_iuu_fishing].

[9] Antarctic Ocean Alliance

.

^http://www.antarcticocean.org

.

[10] The Last Ocean: Ross Sea

.

‘The Last Ocean was started in 2004 to promote the establishment of a marine protected area (MPA) in order to conserve the pristine qualities of the Ross Sea, Antarctica.

In August 2009, the Last Ocean Charitable Trust was created as an extension of this project, specifically to raise awareness of the Ross Sea within New Zealand. The Trust is based in Christchurch, New Zealand’s gateway to Antarctica.’ Visit website: ^http://www.lastocean.org/

.

[11] Ross Sea Dependency

.