Dingo: Australia’s ancient apex predator at risk

Wednesday, April 18th, 2012 Pure Dingo

(Canis lupus ssp. dingo)

Rare and ‘Vulnerable’ on Fraser Island, Queensland

Pure Dingo

(Canis lupus ssp. dingo)

Rare and ‘Vulnerable’ on Fraser Island, Queensland

.

The Dingo is possibly as old as the last Ice Age

.

The earliest archaeological evidence for dingoes in Australia, indicates that the arrival of dingoes in Australia can be dated back to about 18, 000 years BP (before present), based upon mitochondrial DNA data collected by scientists from The Royal Society. [Source: ^http://savefraserislanddingoes.com/pdf/Evolution%20of%20the%20Dingo.pdf, [>Read Report (512kb) ]

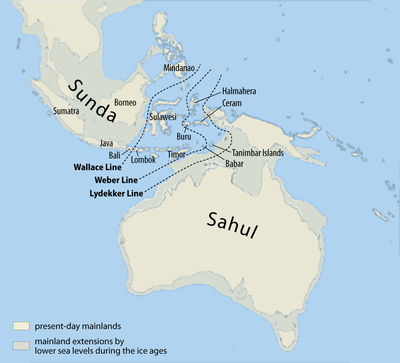

Significantly, 18,000 BP was when the last Ice Age ended in Australia, referred to as the Last Glacial Period (Glacial Maximum) when much of the world was cold, dry, and inhospitable. It is the geological epoch in world evolution known as the Pleistocene Epoch, which in archaeology corresponds to the end of the human Paleolithic Age. At this time, Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania were one land mass called Sahulland. Note, this is not to be confused with ‘Gondwanaland‘, which existed between about 510 to 180 million years ago (Mya).

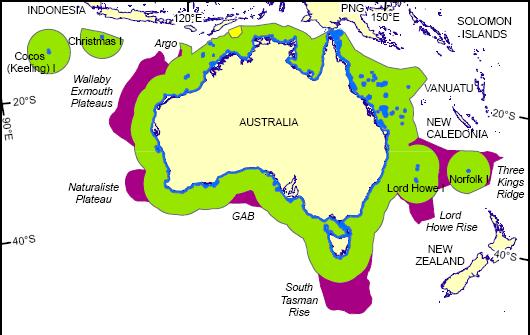

Sahulland or just ‘Sahul‘ was the name chosen by archaeologists at a conference in 1975 [Allen, J.; J. Golson and R. Jones (eds) (1977). Sunda and Sahul: Prehistorical studies in Southeast Asia, Melanesia and Australia’]. Other names offered include ‘Australasia‘ and ‘Greater Australia‘, and this larger land mass forms the basis of Australia’s Continental Shelf, half of which is less than 50 metres deep under the Torres Strait to New Guinea and Bass Strait to Tasmania.

Evolutionary global warming melted the glacias and so rose sea levels, which overflowed the interconnecting lowlands and separated the continent into today’s low-lying arid to semi-arid mainland and the two mountainous islands of New Guinea and Tasmania. Not surprisingly, flora and fauna across these long separate lands have a comparable biota. Since Papua New Guinea and Australia were connected via a land-bridge until 6,000 years ago, travelling from one to the other would have been possible.

DNA-analysis has shown that New Guinea Singing Dogs have a genetic line back to Australian dingos. Genetic analysis reported in March 2010 by Australian Geneticist Dr. Alan Wilton (1953-2011), from the UNSW School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences found the mtDNA-type A29 among Australian dingoes concluded overwhelmingly that genetically, the Australian Dingo and the New Guinea Singing Dog are closely related to each other.

Australian Geneticist Dr. Alan Wilton (1953-2011)

an expert on Australian Pure Dingos

Australian Geneticist Dr. Alan Wilton (1953-2011)

an expert on Australian Pure Dingos

.

Dr Alan Wilton’s study paper published in the journal Nature suggests that those two breeds are the most closely related to wolves and may be most like the original domesticated dog as it was across Asia and the Middle East thousands of years ago, according to one of the 37 authors of the study, making both Australia’s dingo and the New Guinea Singing Dog possibly the world’s oldest dog breeds.

“This paper examines the domestication of the dog from the wild wolf using genetic differences,” Dr Wilton says. “48,000 sites in the dog genome were examined in hundreds of wolves, almost a thousand dogs from 85 modern breeds of dog and several ancient dog breeds. “The data suggest most dogs were domesticated in the Middle East, which was the cradle of agriculture 10,000 of years ago, rather than in Asia as had been suggested previously.

“It also shows dingoes, which have been separated from other breeds of dog in Australia for the past 5,000 years, are the most distinct dog group with most similarity to wolves.”

The dingo and New Guinea Singing Dog stand out as being most different from all other breeds of dogs and closer to wolves than other breeds.

To gather all of the results from many dog breeds and wolves from many locations, a worldwide effort was mounted. Dr Wilton and Jeremy Shearman – from the School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences and the Ramaciotti Centre for Gene Function Analysis at UNSW – have been working on dingoes and methods to differentiate between pure dingoes and crosses between domestic dogs and dingoes. They contributed the genetic data from seven dingoes, which is a small amount of data but makes a large contribution to the paper. The data from all samples was analysed together at Cornell University and UCLA.

[Source: ‘Dingo may be world’s oldest dog‘, by Bob Beale, 20100318, ^http://www.science.unsw.edu.au/news/dingo-may-be-world-s-oldest-dog/]

New Guinea Singing Dog

(Canis lupus familiaris hallstomi)

An ancient genetically pure dog breed with links to the Australian Dingo

New Guinea Singing Dog

(Canis lupus familiaris hallstomi)

An ancient genetically pure dog breed with links to the Australian Dingo

.

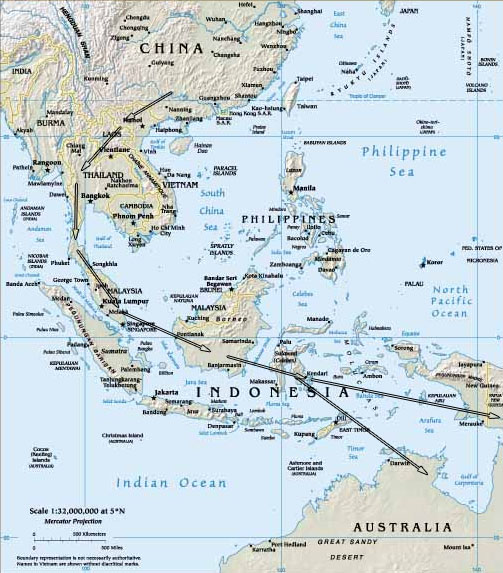

Further biotechnical research published in September 2011 by The Royal Society (UK) has found direct genetic links between ancient Polynesian dogs of South China, Mainland Southeast Asia and Indonesia to the extent that the Dingo has been found to be a direct descendant species dating back to 18,000 BP. The oldest dog remains found in the world are fragments of a dog’s skull and teeth discovered in a cave in Switzerland dating back more than 14,000 years BP, so the dingo is 4000 years older that this.

Genetic study by Klutsch and Savolainen in 2011 concluded that South China was the probable source population for Dingoes and Singing Dogs dating the arrival of dingoes in Australia between 4,640 years ago and as far back as 18,100 years ago. They find “a clear indication that Polynesian dogs as well as dingoes and NGSDs trace their ancestry back to South China through Mainland Southeast Asia and Indonesia.

[Source: ‘Reflections on the Society of Dogs and Men’, in Dog Law Reporter, 20111108, ^http://doglawreporter.blogspot.com.au/2011/11/canoe-conquests-of-western-pacific-who.html] .

Original Natural Distribution of the Dingoes Ancestors

[Source: ^http://www.naturalhistoryonthenet.com/Mammals/dingo.htm]

Original Natural Distribution of the Dingoes Ancestors

[Source: ^http://www.naturalhistoryonthenet.com/Mammals/dingo.htm]

.

The Dingo is an integral apex predator across Australian ecology

.

As with other canids, over thousands of years the Dingo is a descendent of the wolf (Canis lupus).

Eastern Grey Wolf

(Canis lupus lycaon)

[Source: Long live the big, bad, beautiful, snarling wolf, they are wild animals!

^http://www.lovethesepics.com/2012/03/whos-afraid-of-the-big-bad-beautiful-wolf-56-pics/]

Eastern Grey Wolf

(Canis lupus lycaon)

[Source: Long live the big, bad, beautiful, snarling wolf, they are wild animals!

^http://www.lovethesepics.com/2012/03/whos-afraid-of-the-big-bad-beautiful-wolf-56-pics/]

.

Yet after 18,000 years, the Australia Pure Dingo has evolved into a pure unique subspecies in its own right – ‘Canis lupus ssp. dingo’ [ssp. = subspecies]

.

The Dingo is not a breed of dog, but a distinct subspecies of ancient wolf (Canid lupus).

.

Domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) are a separate subpecies of wolf, and of course domestic dogs have multiple breeds mainly due to human interference, referred to as ‘selective breeding‘. Other modern subspecies of the ancient wolf is the Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus lupus), the Coyote (Canis latrans) and the Black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas) as well as many other subspecies globally.

Coyote (Canis latrans)

[Source: ^http://true-wildlife.blogspot.com.au/2011/02/coyote.html]

Coyote (Canis latrans)

[Source: ^http://true-wildlife.blogspot.com.au/2011/02/coyote.html]

.

The Dingo for thousands of years has been Australia’s largest mammalian predator. It has evolved to become an integral part of the native Australian ecology, as apex (top order) predators at the top of the natural food chain and highly adaptive and naturally distributed across every habitat and region of Australia, except Tasmania.

The Dingo’s natural prey consists of small native mammals and ground-dwelling birds, as well as small kangaroos and similar ‘macropods‘ (kangaroo botanical family ‘Macropodidae‘). In this way, naturally occurring population of dingoes has played a key role in maintaining the populations and diversity of these native species.

Unlike domestic dogs, the Dingo yelps and howls, but generally does not bark. It has a different gait to domestic dogs with almost with a cat-like agile habit. Its ears are always erect and it uses its paws like hands. In its natural state the Dingo lives either alone or in a small group unlike many other wild dog species which may form packs. Dingoes tends to survey their surroundings from a height.

Whereas traditional Aboriginal occupation of Australia evolved over thousands of years with harmonious ecological interaction and respect, European colonial invasion of Australia and the widespread deforestation and introduced species that came with it, has destroyed or otherwise perverted Australia’s natural ecology. Dingos and Colonist-introduced domestic dogs interbreed freely resulting in very few pure-bred dingos in southern or eastern Australia. This is seriously threatening the dingo’s ability to survive as a pure species. Public hostility is another threat to the dingo.

Australian Aboriginal peoples commonly refer to the dingo as the ‘Warragul‘. This name has been used for a town 100km south-east of Melbourne, reflective of the traditional presence of the dingo as far south as southern Victoria. Other Aboriginal names for Dingo across Australia include include ‘binure‘ and ‘mirragang‘ (Gundungurra language), ‘mirri‘ (Darug language), ‘nurragee‘ and ‘mirragang‘ (Tharawal language).

.

Pure Dingo at Risk of Extinction

.

Pure-bred Dingo numbers in the Australian wild are declining as Colonists and their decendants continue to encroach deeper into wilderness areas, releasing feral dogs that inevitably compete, socialise and breed with pure Dingoes.

Professor Bill Ballard of the School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences at the University of New South Wales has conducted research showing that there are few remaining pure dingoes are left in wild. [Read More].

According to Dr. Alan Wilton’s mitochondrial DNA testing of Dingoes from 2000, most Dingo populations throughout Australia are 80% hybrids, with some 100% hybrids. Only a few populations remain ‘Pure Dingo‘. One area isolated from colonial incursion is the southern Blue Mountains region of New South Wales, which has been designated a Dingo Conservation Area, supposedly to control wild dogs in this area in order to prevent cross-breeding with pure Dingoes and the hybridisation of the Dingo species. [>Read More (480kb) ]

In 2005, the Dingo was listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as ‘Vulnerable‘ due to a 30% decrease in numbers (IUCN = ‘International Union for Conservation of Nature’). [^Read More]

However, the IUCN wrongly groups the Australian Dingo (Canis lupis ssp. dingo) with the New Guinea Singing Dog (Canis lupus familiaris hallstomi) and with other South East Asian dogs under its Red List classification ‘Canis lupus ssp. dingo‘. This fails to assign proper genetic distriction of the Pure Australian Dingo as a discrete subspecies, which has evolved in Australia over thjousands of years quite separately from these other South East Asian subspecies. The IUCN contradictorily uses the term ‘dingo’ to refer to the Australian Pure Dingo and at the same time in a generic sense as a common name to describe the wild dogs of Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and New Guinea. The IUCN interpretation is contradictory and wrong.

.

The ‘Australian Pure Dingo’ is not a Polynesian domestic dog!

.

On the one hand , the IUCN explains the difficulty of distinguishing pure dingoes from hybrids and states that the “pure form may now be locally extinct (Corbett 2001)” and that “such quantitative data is not available for countries other than Australia, Thailand and Papua New Guinea“. Yet the IUCN website shows only two known mapped locations of this subspecies – both being on Fraser Island (Aboriginal: K’Gari).

The IUCN concludes that where the most genetically intact populations live is where conservation efforts should be focused.

Fraser Island (K’Gari)

Showing possibly the last of the planet’s Australian Pure Dingo distribution,

according to the IUCN in 2011

[Source: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, version 2011.2, ^http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=41585]

Fraser Island (K’Gari)

Showing possibly the last of the planet’s Australian Pure Dingo distribution,

according to the IUCN in 2011

[Source: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, version 2011.2, ^http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=41585]

.

Given the severely restricted distribution of the Pure Australian Dingo, this subspecies deserves discrete classification and listing by the IUCN as ‘Critically Endangered‘. Clearly more intensive research by the IUCN is warranted, particularly recognising the recent and expert studies in this specific field by Professor Bill Ballard, Dr Alan Wilton and Jeremy Shearman, amongst others.

Recognition of the Pure Australian Dingo as at risk is given inconsistent hotch-potch protection by Australian jurisdictions. In New South Wales (NSW), Dingo populations from Sturt National Park, the coastal ranges and some coastal parks have been nominated as endangered populations under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995. At Australian national level and under the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974, the Dingo remains unprotected despite being considered a native species. Under the Rural Lands Protection Act 1998 (NSW), Dingoes are still declared a pest species, a throwback to the colonial mindset.

Dr Wilton predicts that within 100 years, the pure dingo will be extinct in the wild.

.

‘Dingo’s are going away the Thylacine unfortunately, unless somebody does something about it soon we won’t have any dingo’s left.’

The Thylacene

Persecuted by misguided Colonists until its extinction in the 1930s

The Thylacene

Persecuted by misguided Colonists until its extinction in the 1930s

.

Dr Wilton has identified that there remains only one genetically confirmed population of pure dingoes – those on Queensland’s Fraser Island – perhaps as few as 120 individuals left. This clan was long isolated from early colonial invasion and disturbance, but in recent times has increasingly been threatened by growing tourism incursions (400,000 tourists annually) and mismanagement and persecution by Queensland wildlife rangers. Yet despite the precarious viability of this precious pure Dingo population, in 2001 Queensland Labor Premier Peter Beattie ordered a mass slaughter of forty dingoes in retribution for a boy tourist being killed that year by Dingoes on the island. [>Read More]

Clearly the Queensland Labor Party and the delegated custodian, the Department of Environment and Resource Management (DERM) (or whatever its latest rebranded name) values Fraser Island for anthopocentric tourism more than the survival of the Australian Dingo as a species. Fraser Island is World Heritage Listed, but the Queensland Government has always interpreted this as a tourism branding strategy.

.

‘Genetically pure dingoes face extinction’

.

[Source: ‘Genetically pure dingoes face extinction’, by Peter McAllister (science writer and anthropologist from Griffith University), 20110311, ^http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/dingo-populations-at-risk-from-hybrids.htm].

‘Dingoes are often in headlines for all the wrong reasons – agressive behaviour to tourists, culls by national park authorities – but behind the scenes, conservationists hold concerns that dingoes may be interbred into extinction.

Fears for the dingo’s future are proliferating. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) upgraded the dingo’s conservation status to vulnerable in 2004 and dingo experts such as Dr Ricky Spencer from the University of Western Sydney, have predicted Australia’s native canine will go extinct within the next twenty years.

Purebred Dingo

(Photo: Bradley Smith)

[Source: ^http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/dingo-populations-at-risk-from-hybrids.htm]

Purebred Dingo

(Photo: Bradley Smith)

[Source: ^http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/dingo-populations-at-risk-from-hybrids.htm]

.

But it’s not just their white socks that are changing though. One recent study found that average dingo weight and size has risen by 20 per cent over the past two decades, probably because of hybridisation. This change could alter the way dingoes hunt, allowing them to attack livestock and wildlife they’ve previously found an unmanageable size.

Behavioural changes also cause ecological problems. There is some evidence, for instance, that the dingo breeding season has grown longer under the influence of domestic dog genes; dogs breed twice a year, in contrast to the dingo’s single season. This might be one reason for the explosion in dingo and wild dog numbers across the country.

Another might be the breakdown in the pack structure of dingo societies. In the wild, dingo packs sometimes centre around a breeding alpha pair which suppress the breeding of subordinate members – a possible natural population control measure. Domestic dogs, however, seem to form larger packs with uncontrolled breeding, again possibly contributing to the current population explosion.

Hybridisation with domestic doges is the Dingo’s greatest threat. Dingoes and domestic dogs, both subspecies of Canis lupus, can interbreed with ease and this has led to a massive influx of domestic dog genes into the dingo gene pool.

In many places around Australia (some experts say ‘most‘) dingoes have been almost totally replaced by dog-dingo hybrids. Even those animals that appear to be dingoes are often now, in reality, mostly domestic dogs. “The only way to tell for sure,” says Dr Guy Ballard, a dingo researcher with the NSW government’s vertebrate pest unit, “is by analysing their skulls, or taking DNA samples”.

But it’s not just their white socks that are changing though. One recent study found that average dingo weight and size has risen by 20% over the past two decades, probably because of hybridisation. This change could alter the way dingoes hunt, allowing them to attack livestock and wildlife they’ve previously found an unmanageable size..

.

Saving the Purebred Dingo

.

This inexorable tide of hybridisation has lent new urgency to the question of how best to save the dingo. Most experts are pessimistic about the chances of preventing interbreeding, pointing out that contact between dog and dingo populations is only going to increase.

Some proponents advocate the establishment of refuges where remnant populations of pure dingoes could be maintained. The best known of these is Fraser Island, where the Great Sandy National Park protects what is regarded as the purest population of dingoes left in Australia. However, the culling of problem dingoes on the popular tourist island has led to fears that the dingo population there is now too small to be genetically viable.

Such concerns have led some conservationists to opt for a different strategy: establishing their own private breeding refuges on the mainland instead. One such is the Australian Dingo Conservation Association’s (ADCA) 92 ha compound at Colong station in the Blue Mountains National Park.

There the ADCA maintains a breeding population of 31 purebred dingoes.

“We try hard to maintain that genetic purity,” says ADCA vice-president Gavan McDowell. “We even separate our breeding packs into sub-types, like mountain, desert and tropical dingoes.”

The Association’s ultimate aim is to breed a number of pure dingoes that can be released into the wild to recolonise areas, cleared of feral dogs.

Silver Lining

.

Other researchers, like Guy, are more optimistic of the dingo’s plight.

His research includes several field projects looking at dingo purity around Australia. While Guy acknowledges that hybridisation is a major threat, he says that wherever his group tests dingoes, even in heavily hybridised areas of NSW, they still find good numbers of purebred dingoes.

“People often don’t realise that the environmental factors that lead to large numbers of hybrids also mean large numbers of pure dingoes,” Guy says. “It’s impossible to prove, but I suspect there are actually more purebred dingoes around today than at any other time in history.”

Best of all, says Guy, is the fact that his team has identified several hotspots where pure dingo numbers are consistently high. One is the Tanami Desert, where the dingo population is 90 per cent pure, apparently due to the area’s remoteness. Two others, however, lie on the heavily settled NSW coast: at Myall Lakes National Park and Limeburners Creek Nature Reserve.

Quirks of geography – Limeburners Creek is on a peninsula, and Myall Lakes is connected by green belts to the wilder lands out to Sydney’s west – have apparently allowed both areas to sustain populations of pure dingoes, despite their proximity to settled areas with large populations of domestic dogs.

Guy also believes that with careful management – such as continual DNA tests to identify and euthanise hybridised dogs – the populations at Limeburners Creek and Myall Lakes can maintain their purity for some time to come.

“Dingoes have survived two hundred years of interbreeding already,” he says.

“I don’t see why, with a little help, they can’t survive for another two hundred.”

.

Aboriginal Respect for Dingoes

.

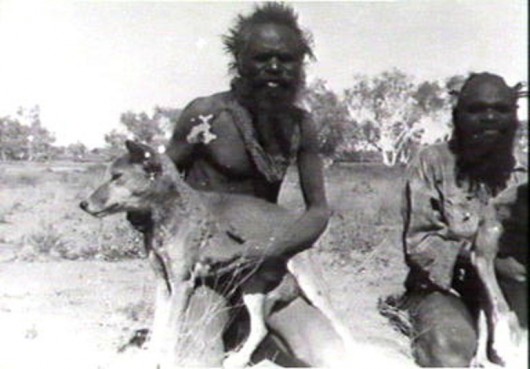

‘Following its arrival into Australia, the dingo was readily accepted into Aboriginal life, both practically and spiritually. Dingoes have long been valued companion animals to Aboriginal peoples, serving as hunting companions, camp guard dogs, camp cleaners and as bed warmers on cold nights.

Spiritually, dingoes have been regarded as a protector (particularly by traditional Fraser Island tribes) and representing ancestral spirits – able to perceive the presence of evil spirits undetectable by humans. Mythological or Dreamtime stories about the Dingo in Aboriginal cultures across Australia are for Aboriginal people to convey.

Dingoes are valued companion animals to traditional Aboriginal peoples

Dingoes are as Australian as Aboriginal peoples.

Dingoes are valued companion animals to traditional Aboriginal peoples

Dingoes are as Australian as Aboriginal peoples.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘Vanishing Icon: The Fraser Island Dingo‘, by Jennifer Parkhurst, 2010, Print, published by Grey Thrush Publishing, St Kilda, Victoria, Australia, ^http://savefraserislanddingoes.org.au/shop/store/products/jennifer-parkhursts-book-vanishing-icon/.

.

[2] Fraser Island Footprints (website), ^http://www.fraserislandfootprints.com/“It’s the Dingo’s environment, WE are the ones who should be monitored. Please leave them alone, let them live their lives how they should be lived, NOT HALF STARVED. Please go to Fraser Island and look for yourself, then feel what your conscience tells you.” ~ Australia.

.

[3] ‘Reflections on the Society of Dogs and Men‘, Tuesday, November 8, 2011, in Dog Law Reporter, ^http://doglawreporter.blogspot.com.au/2011/11/canoe-conquests-of-western-pacific-who.html.

[4] ‘Genetic diversity in the Dingo‘, by Professor Bill Ballard [Head of School], School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences -Faculty of Science, University of New South Wales, ^http://www.dingosanctuary.com.au/dna.htm.

[5] ‘Dingos of Fraser Island‘, by John Sinclair, Honorary Project Officer, Fraser Island Defenders Organisation Fraser Island Deferendres Organisation, ^http://www.fido.org.au/moonbi/DingoStory20010502.html, Website: ^http://www.fido.org.au/.

[6] ‘Threatened and Pest Animals of Greater Southern Sydney‘, Chapter 3, New South Wales Government, Department of Environment (et.al), ^http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/threatenedspecies/07227tpagssch3pt1.pdf.

[7] Save the Fraser Island Dingo Inc., ^http://savefraserislanddingoes.com/“Fraser Island (K’gari) lies off the coast of Queensland, Australia, approx. 200k (120miles) north of Brisbane. It is the largest sand Island in the world. In 1992 it was World Heritage listed by UNESCO because of its natural beauty and unique flora and fauna. The apex predator on the Island is the dingo (canis lupus dingo) and may well be one of the last pure strains of dingo remaining in Australia. The conservation of this gene pool is of national significance.”

.

[8] ‘The great dingo dilution‘, by Steve Davidson, ECOS Magazine, Vol. 118, Jan-Mar 2004, pp. 10-12., ^http://www.ecosmagazine.com/?paper=EC118p10“Australia’s only wild dog, the iconic dingo, has survived a couple of hundred years of persecution – from shooting, trapping and poisoning. Ironically, it is now at grave risk of disappearing. The greatest threat isn’t so much over-hunting or the usual culprit, habitat destruction; it’s the friendly domestic dog.” [>Read article (1140kb)]

.

[9] ‘Pure-bred dingoes might run free on city’s doorstep‘, by James Woodford, 20050903, ^http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/purebred-dingoes-might-run-free-on-citys-doorstep/2005/09/02/1125302746483.html.

[10] ‘Dingo Attack of unsupervised toddler‘