Archive for the ‘Tasmanian Devils’ Category

Wednesday, May 2nd, 2012

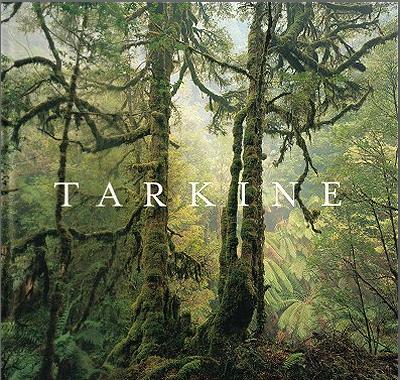

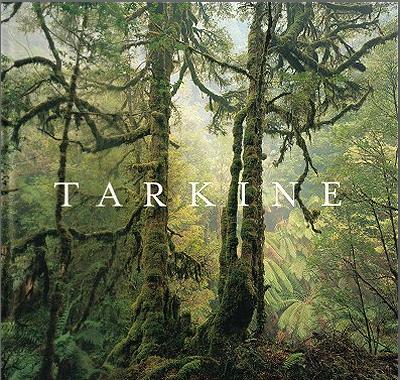

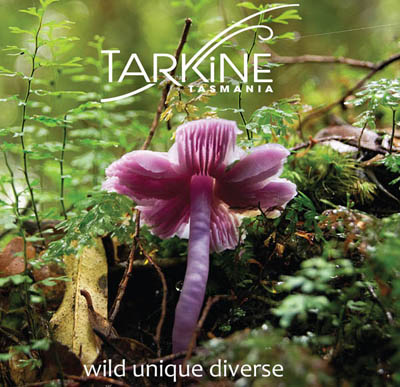

‘Tarkine Tasmania: wild, unique, diverse’ ‘Tarkine Tasmania: wild, unique, diverse’

(A photographic essay of exploration into this unique wilderness)

Images and text courtesy of Jenny Archer and Jen Evans

Purchase book: ^http://www.tarkineimages.com.au/purchase.html

[$5 from every copy sold will be donated to the Tarkine National Coalition – an organisation committed to protecting the Tarkine]

.

The unique Tarkine

.

Tasmania’s Tarkine Wilderness is one of the few remaining wild temperate rainforest regions left on the planet!

‘The Tarkine‘ is named after the Tarkiner people who traditionally inhabited the region from 30,000 years ago. It stretches from Tasmania’s wild coastline to the west, the Arthur River to the north, the Pieman River to the south, and the Murchison Highway to the east.

The Tarkine contains remarkable natural and cultural values, including one of the world’s most significant remaining tracts of temperate rainforest. The Tarkine covers an expansive 447,000 hectare (4,470 km2) wilderness region of recognised World Heritage significance up in the North-West corner of Tasmania, containing the largest temperate (Myrtle-Beech) rainforest in Australia.

Tasmania’ Tarkine Wilderness is indeed ‘wild, unique and diverse‘.

Myrtle Beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii)

An evergreen tree native to Victoria and Tasmania, but hardly any now left in Victoria.

Typically grow to 30–40 metres (98–130 feet) tall Myrtle Beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii)

An evergreen tree native to Victoria and Tasmania, but hardly any now left in Victoria.

Typically grow to 30–40 metres (98–130 feet) tall

.

The Tarkine is the largest surviving region of Nothofagus Forest left on the planet

The Tarkine is the largest surviving region of Nothofagus Forest left on the planet

.

The Tarkine compared internationally

.

‘The Tarkine‘ is the same size as internationally well-respected national parks:

- New Zealand’s Kahurangi National Park (4,520 km2)

- United States’ Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona (4,927 km2)

- Indonesia’s Tanjung Puting National Park in southern Borneo (4,150 km2)

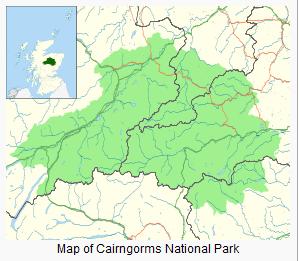

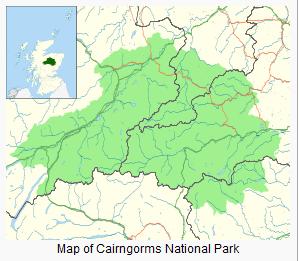

- Scotland’s Cairngorms National Park (4,528 km2) …per map below:

Scotland has a Tarkine wilderness equivalent – ‘Cairngorms’ Scotland has a Tarkine wilderness equivalent – ‘Cairngorms’

.. respected as a National Park

.

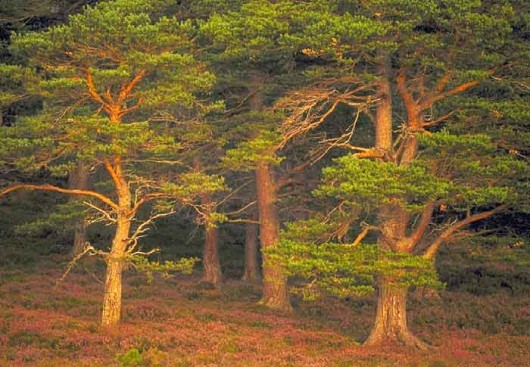

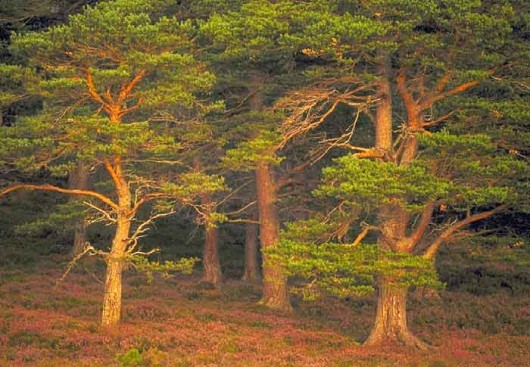

Rare ancient Caledonian Forest

Rare ancient Caledonian Forest

in Cairngorms National Park, Scotland

(the same size as Tasmania’s Tarkine)

The Cairngorms National Park is special because it contains the best arctic-alpine landforms, habitats and species in Britain. This is one of the few places where wild nature is so easy to see and many of the plants and animals living here are at the extreme edges of their geographical ranges.

^http://www.cairngormslearningzone.co.uk/habitats-species.html

.

Compare The Cairngorms with The Tarkine of a similar size. The Tarkine is a relict from the ancient super-continent, Gondwanaland, characterised by highly diverse ecosystems from giant ancient forests to huge sand-dunes, sweeping beaches, rugged mountains and pristine river systems. [Sources: ^http://tarkine.org/, ^http://www.corinna.com.au/Story/Tarkine.aspx]

The Tarkine has more than 400 species of diverse flora, including a range of native orchids and many rare and threatened species. There are more than 250 vertebrate species of fauna, 50 of which are rare, threatened and vulnerable.

These include:

- Spotted-tailed Quoll

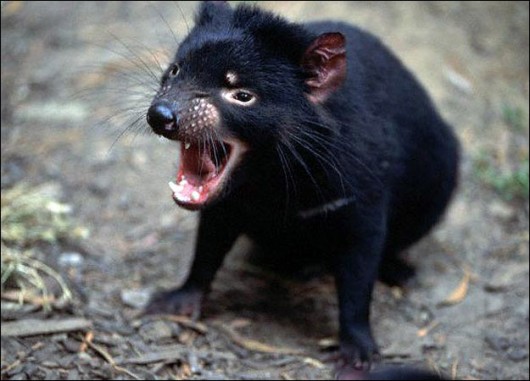

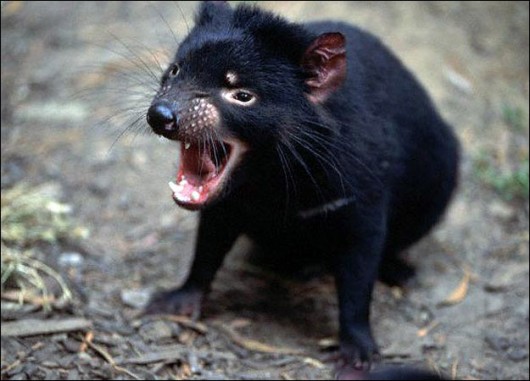

- Tasmanian Devil

- Eastern Pygmy Possum

- Wedge-tailed Eagle

- White-breasted Sea Eagle

- Grey Goshawk (white morph)

- Giant Freshwater Lobster

- Orange-bellied Parrot (on the brink of extinction)

.

A now ‘Endangered‘ Tasmanian Devil captured on motion-sensitive camera

Walkers join forces with conservationists through Tasmania’s remote Tarkine rainforest to help bring the Tasmanian Devil back from the brink of extinction.

[Source: ‘Tourists to use cameras to help save Tasmanian Devil’ by Dominic Bates, The Guardian (UK), guardian.co.uk, 20120203, Read More: ^http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/feb/03/tourist-cameras-save-tasmanian-devil]

(Photo courtesy of Tarkine Trails, Feb 2012)

.

A now ‘Endangered‘ Tasmanian Devil captured on motion-sensitive camera

Walkers join forces with conservationists through Tasmania’s remote Tarkine rainforest to help bring the Tasmanian Devil back from the brink of extinction.

[Source: ‘Tourists to use cameras to help save Tasmanian Devil’ by Dominic Bates, The Guardian (UK), guardian.co.uk, 20120203, Read More: ^http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/feb/03/tourist-cameras-save-tasmanian-devil]

(Photo courtesy of Tarkine Trails, Feb 2012)

.

The Cairngorms are similarly ancient, a glacial landscape formed 40 million years before the last Ice Age. The area also features a rare ancient woodland, the Caledonian Forest, as well as unique alpine semi-tundra moorland habitat.

The moorland provides important habitat to many rare plants, birds including Ospreys, breeding Ptarmigan, Dotterel, Snow Bunting, Golden Eagle, Ring Ouzel, and Red Grouse, with Snowy Owl, Twite, Purple Sandpiper and Lapland Bunting seen on occasion. The Caledonian Forest supports rare birds such as the endangered Capercaillie and endemic Scottish Crossbill (found nowhere else on the planet), the Parrot Crossbill and the Crested Tit.

The Scottish Crossbill

..unique to the Cairngorms The Scottish Crossbill

..unique to the Cairngorms

.

The Cairngorms is also home to:

- Red Deer

- Roe Deer

- Mountain Hare

- Pine Marten

- Red Squirrel

- Wild Cat

- Otter

- as well as the only herd of Reindeer in the British Isles..

Cairngorms Reindeer

Source: ^http://www.scotlandweb.be/photos.htm

Cairngorms Reindeer

Source: ^http://www.scotlandweb.be/photos.htm

.

Meanwhile, The Tarkine is home to more than 130 different species of birds during the seasons throughout its variety of habitat types and landscapes. This includes eleven of Tasmania’s twelve endemic birds. The two migratory species that breed only in Tasmania, the ‘Endangered‘ Swift Parrot, and the ‘Critically Endangered‘ Orange-bellied Parrot, forage in the Tarkine.

Orange–bellied Parrot (Neophema chrysogaster)

critically dependent upon The Tarkine

In 2010 it was ranked by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Services as one of the world’s rarest and most endangered species and “on the brink of extinction“ Orange–bellied Parrot (Neophema chrysogaster)

critically dependent upon The Tarkine

In 2010 it was ranked by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Services as one of the world’s rarest and most endangered species and “on the brink of extinction“

.

Orange-bellied Parrot numbers down to about 20 individuals in existence!

Watch ABC News ^Video (February 2012) Orange-bellied Parrot numbers down to about 20 individuals in existence!

Watch ABC News ^Video (February 2012)

The Orange-bellied Parrot breeds in south-west Tasmania and migrates along the west coast (The Tarkine) and forages on coastal plants. Consequently the Tarkine’s coastal vegetation is extremely important habitat. The endangered Swift Parrot breeds predominantly in south-east Tasmania and feeds on the nectar from the Tasmanian Blue Gum, and in the Tarkine, the Swift Parrot forages on these trees during the post-breeding dispersal and migration season.

The Tarkine’s bird species richness is correlated to the Tarkine’s rich habitat diversity; the sea, coastal shores, freshwater wetlands, streams and estuaries, heathland-moorland mosaic of the coastal plains, woodland and open forests, wet eucalypt forests, mixed forest and extensive rainforest.’

[Source: Tarkine National Coalition, ^http://tarkine.org/birds/]

.

National Park Protection

.

The Cairngorms ecological values were recognised and protected as a National Park (NP) by the new Scottish Parliament in 2003. [Read More: ^www.cairngormscampaign.org]

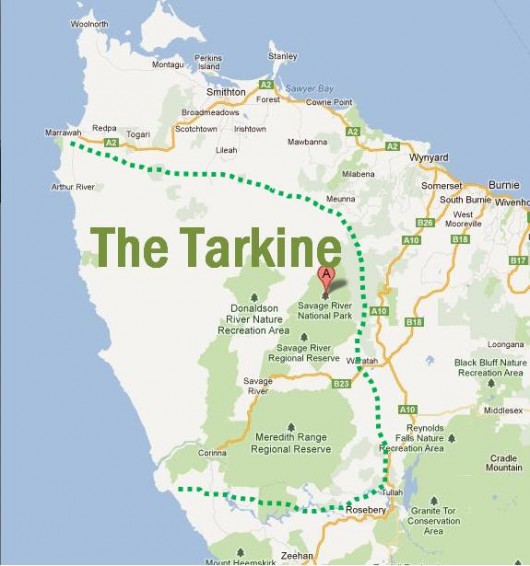

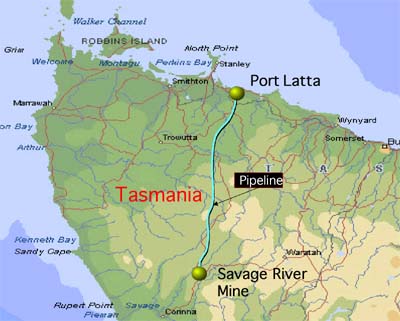

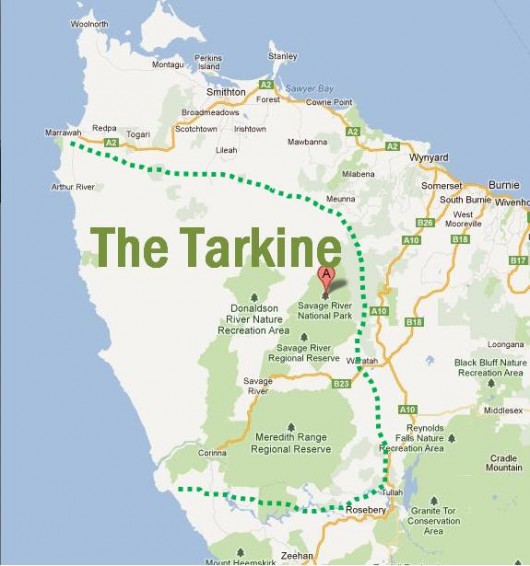

But unlike the Cairngorms NP, Kahurangi NP, Grand Canyon NP and Tanjung Puting NP, just less than 5% of The Tarkine is protected as a National Park. Within the Tarkine region’s 4,470 km2, recognised as bounded by the coast to the west, the Arthur River to the north, the Pieman River to the south, and the Murchison Highway to the east, only Savage River National Park (180km2) , less than 5% of The Tarkine, provides any formal ecological protection.

The ‘Donaldson River Nature Recreational Reserve’, the ‘Meredith Range Recreational Reserve’ and the Arthur Pieman Conservation Area within The Tarkine offer no formal ecological protection and are open to mechanised recreational abuse. See map below. Propaganda by vested interests would have many believe that these reserves offer sufficient ecological protection, but such reserves permit multiple uses – motorised vehicular access including off-road, as well as road making, logging, burning, mining, poaching of wildlife, fishing, farming and tourism development – so effectively offering no ecological protection.

[Read the propaganda in The (Launceston) Examiner newspaper: ‘Mining heritage’, 20110320, ^ http://www.examiner.com.au/news/local/news/environment/mining-heritage/2108235.aspx?storypage=0]. The Examiner threatened: “If successful the campaign of the Tarkine National Coalition will perpetrate an injustice on local people leading to negative impacts on both the Tasmanian economy and the quality of life of its people.”

What scaremongering crock! But then who are the readership and who are the sources of advertising revenue of The Examiner?

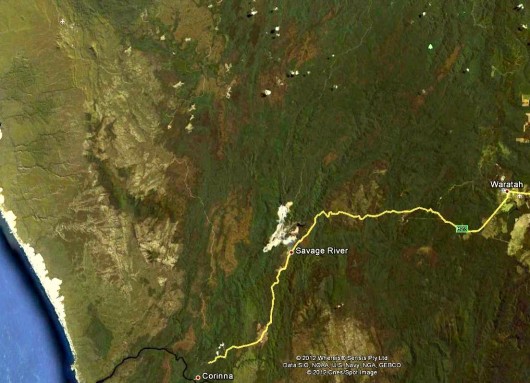

The Tarkine of North-West Tasmania

Note: dotted boundary above is only indicative

(Google Maps)

For a more detailed map of the proposed Tarkine National Park, click here)

[Source: ^http://development.savethetarkine.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/topo_tarkine_boundary.jpg] The Tarkine of North-West Tasmania

Note: dotted boundary above is only indicative

(Google Maps)

For a more detailed map of the proposed Tarkine National Park, click here)

[Source: ^http://development.savethetarkine.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/topo_tarkine_boundary.jpg]

.

Savage River National Park

(inside The Tarkine)

.

Savage River National Park is described by the Tasmanian Government’s Parks and Wildlife Service as follows:

. .

‘Savage River National Park is a wilderness region in the north west of Tasmania. The park protects the largest contiguous area of cool temperate rainforest surviving in Australia and acts as a refuge for a rich primitive flora, undisturbed river catchments, high quality wilderness, old growth forests, geodiversity and natural landscape values.

The western portion of the park includes the most extensive basalt plateaux in Tasmania that still retains a wholly intact forest ecosystem. The upper Savage River, which lends the park its name, runs through a pristine, rainforested river gorge system. The park contains habitat for a diverse rainforest fauna and is a stronghold for a number of vertebrate species which have suffered population declines elsewhere in Tasmania and mainland Australia.

The parks remoteness from human settlement and mechanised access, its undisturbed hinterland rivers and extensive rainforest, pristine blanket bog peat soils and isolated, elevated buttongrass moorlands ensure the wilderness character of the park. Like the vast World Heritage listed Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area to its south, the area is one of the few remaining temperate wilderness areas left on Earth.

Unlike other national parks, Savage River National Park remains inaccessible. In keeping with its wilderness character, there are no facilities and no roads or mechanised access to the park. However, the park is surrounded by the Savage River Regional Reserve, in which a number of rough 4WD tracks provide limited access. To the north of the reserve, a number of State Forest Reserves can be accessed by standard vehicles. They offer an insight into the magnificent rainforest ecosystem that lies to the southeast within the Savage River National Park.’

[Source: Parks and Wildlife Service, Tasmania, ^http://www.parks.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=3732]

.

But the above description is only a tiny snapshot of The Tarkine

The Tarkine still is undoubtedly one of the World’s great wild places

Giant Eucalyptus regnans of The Tarkine

Giant Eucalyptus regnans of The Tarkine

(click image to enlarge)

.

The Tarkine’s World Heritage significance

.

The Tarkine is a region of recognised World Heritage significance. It’s wilderness, vast rainforests, wildlife, landscapes and unique Aboriginal values are outstanding on a world scale.

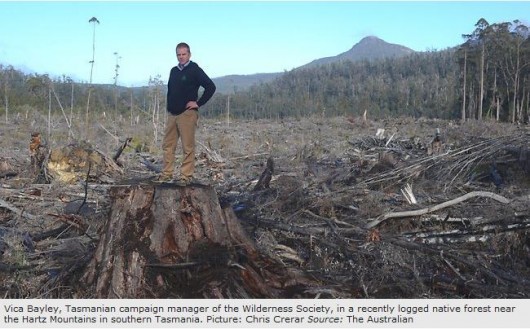

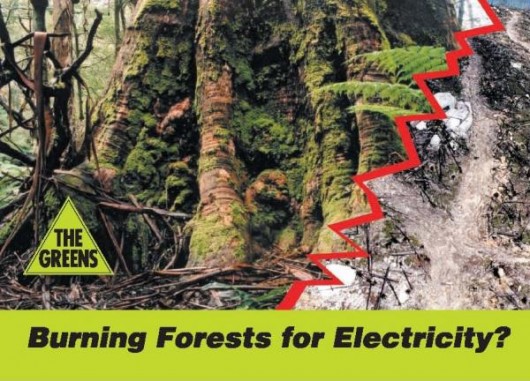

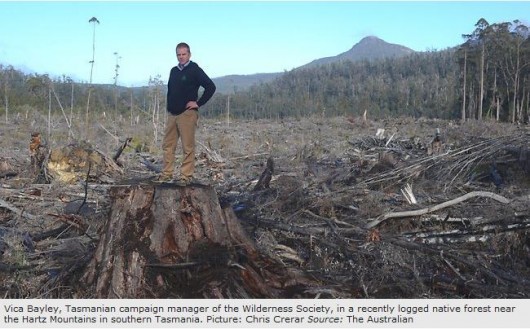

However, the Tarkine is not protected as a National Park nor listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Only a fraction, less than 5%, of the Tarkine region is fully protected as a National Park. This means that many of the Tarkine’s outstanding natural and cultural values, are in dire peril due to repeated exploitation demands from industrial logging and more recently industrial mining.

These industrial threats mean that The Tarkine ecology could be lost forever!

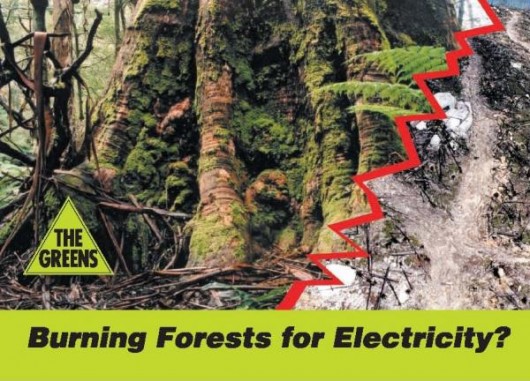

Logging legacy in The Tarkine Logging legacy in The Tarkine

.

Attempts have been made to have The Tarkine listed not only as a National Park, but also as a World Heritage Listed Area.

Local conservation champions of The Tarkine, the Tarkine National Coalition (TNC) have produced an extensive proposal that would protect the Tarkine and its unique values as a National Park and World Heritage area, for all people, for all time, just like Kakadu NP and Cairngorms NP.

Read More:

.

[Source: Australian Government, ^http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/ahc/national-assessments/tarkine/pubs/tarkine-values-summary-2011.pdf]

.

The Tarkine would become recognised as one of Australia’s great iconic wild places, allowing locals, visitors, walkers, photographers, scientists, the Aboriginal community and tourists alike to see, visit and experience this unique place.

A number of prominent bodies have recognised the World Heritage significance of the Tarkine:

- The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (1990)

- The Tasmanian Department of Parks, Wildlife & Heritage (1990)

- The Australian government recognised the Tarkine’s outstanding national significance through listing the Tarkine on the register of the National Estate Leading Tasmanian & Australian environment groups (including The Wilderness Society and the Australian Conservation Foundation, amongst a wide range of others)

- The Australian Senate formally and unanimously recognised the World Heritage significance of the Tarkine (2007).

For the Tarkine to be inscribed on the World Heritage list, it would need to be formally put forward to UNESCO (the United Nations Body) by the Australian Government. Yet, there has been a failure by successive Environment Minister’s to instruct the Australian Heritage Council to commence assessment of the World Heritage values contained within the Tarkine.

.

[Source: ^http://tarkine.org/national-park-and-world-heritage-aspirations/]

.

The natural ecological wealth of Tasmania’s Tarkine Wilderness

(Arthur River rainforest, Photo by Ted Mead) The natural ecological wealth of Tasmania’s Tarkine Wilderness

(Arthur River rainforest, Photo by Ted Mead)

.

On 11 December 2009, Australia’s Environment Minister (then Peter Garrett MP) entered The Tarkine in Australia’s National Heritage List under the emergency listing provisions of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. This emergency listing lapsed in December 2010.

The Australian Heritage Council has since completed a preliminary assessment of The Tarkine and found that The Tarkine might have one or more National Heritage values. It is now up to Australia’s Environment Minister (currently Tony Burke MP) to decide whether The Tarkine, or areas within it, should be listed of Australia’s National Heritage List. So, the fate of this magnificent wild region, effectively Australia’s Amazon, rests with one man, Tony Burke MP.

[Source: Australian Government, ^http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/ahc/national-assessments/tarkine/information.html]

.

Tarkine Threatened by Industrial Miners

.

Despite The Tarkine’s many unique ecological values, there are some who chose to ignore and dismiss The Tarkine for their own self-serving gain. Industrial Miners are seeking to plunder The Tarkine for minerals below ground. If these miners get their way, they will open cut The Tarkine and irreversibly destroy it. The Tarkine’s natural future as a wild region and its dependent wildlife hang in the balance.

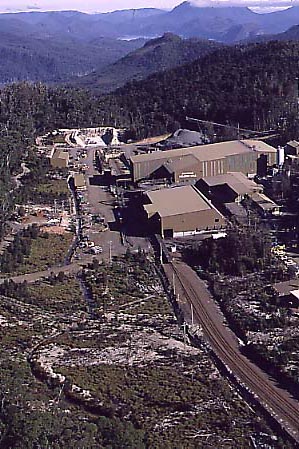

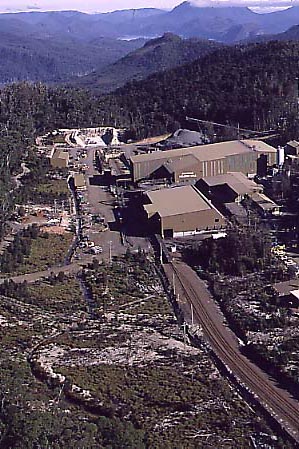

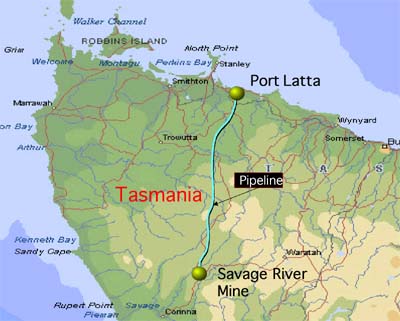

Currently limited mining occurs within parts of the Tarkine. The most significant mining operations within the Tarkine region is the Savage River Iron Ore Mine, which is currently managed by Grange Resources, and the Hellyer Mine managed by Bass Metals.

Savage River Iron Ore Mine

..in the Tarkine Savage River Iron Ore Mine

..in the Tarkine

.

Hellyer Zinc and Lead Mine

..in the Tarkine

Construction of a new underground mine at the Fossey deposit, near Hellyer, began in January 2010. Hellyer Zinc and Lead Mine

..in the Tarkine

Construction of a new underground mine at the Fossey deposit, near Hellyer, began in January 2010.

[Source: Mineral Resources Council (Tas Govt)

^http://www.mrt.tas.gov.au/portal/page?_pageid=35,831239&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL

.

Now there are another 10 new mines proposed to destroy The Tarkine!

.

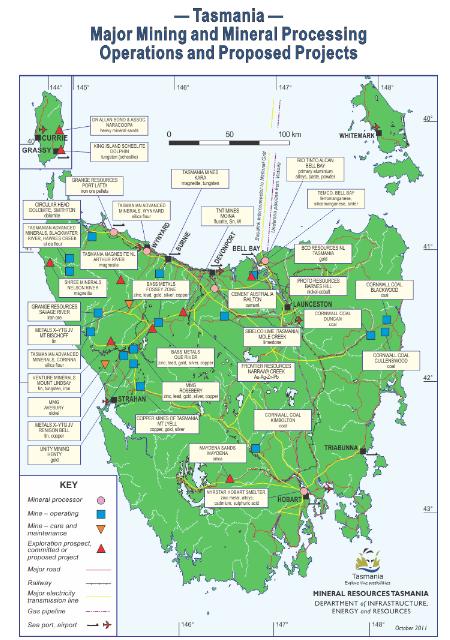

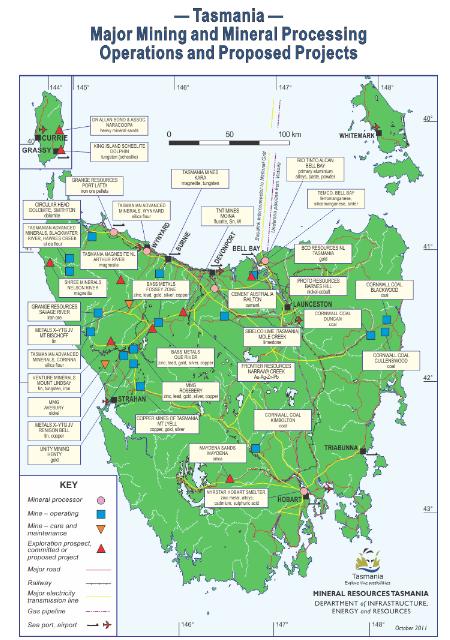

Tasmanian Government’s mining leases (Dec, 2012)

threaten to destroy most of The Tarkine Tasmanian Government’s mining leases (Dec, 2012)

threaten to destroy most of The Tarkine

.

Nine of the planned ten mines are nearby Savage River ‘open-cut’ style mines. The Tasmanian Government under the watch of Labor’s Bryan Green MP has overseen its Tasmanian Mineral Council grant some 56 exploration licences over the Tarkine to 27 different industrial mining companies.

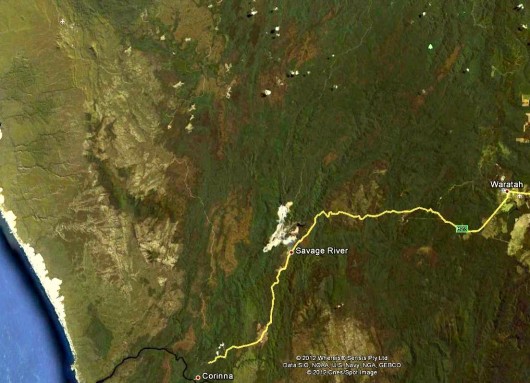

Savage River Mine location map

..already in The Tarkine Savage River Mine location map

..already in The Tarkine

.

Savage River Open Cut Mine

..a harbinger for The Tarkine… landscape absolute anhiliation Savage River Open Cut Mine

..a harbinger for The Tarkine… landscape absolute anhiliation

.

Savage River – a savage scar in The Tarkine

..courtesy of industrial miner Grange Resources

(Google Earth – click image to enlarge) Savage River – a savage scar in The Tarkine

..courtesy of industrial miner Grange Resources

(Google Earth – click image to enlarge)

.

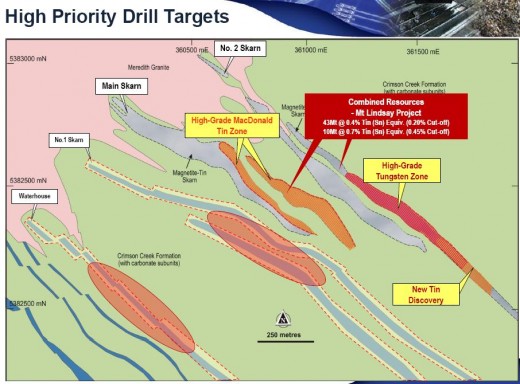

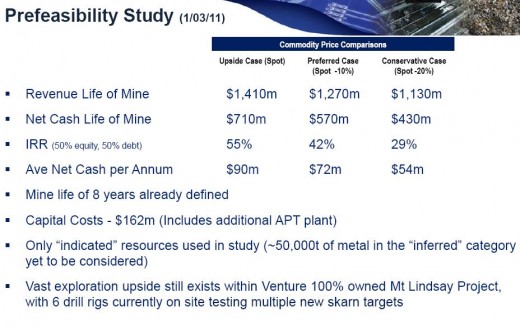

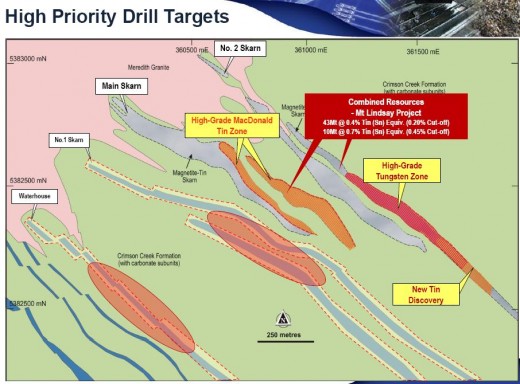

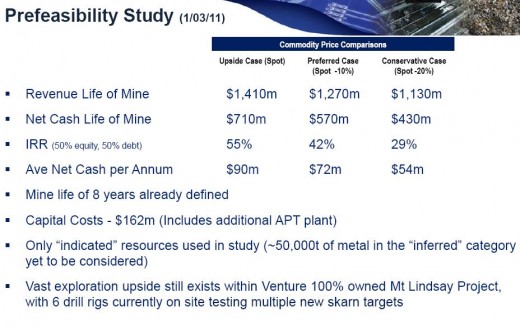

Venture Minerals‘ proposed Tin Mine at Mount Lindsay (2011)

.

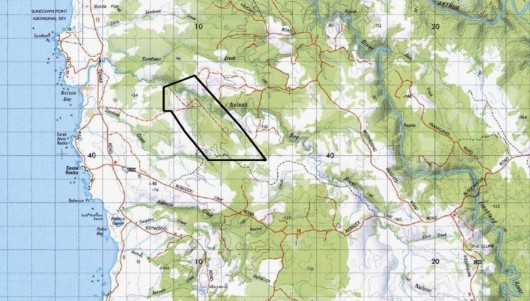

West Australian headquartered Venture Minerals has submitted mining permits to the Tasmanian Government to allow it to develop a tin/tungsten open cut mine at Mount Lindsay, so it can sell Tasmanian resource wealth to China. It will extend over 36,000 hectares (360 km2), creating a permanent scar through The Tarkine, roughly an area the size of the Tamar Valley from Launceston to Georgetown.

Mount Lindsay Tin Mine Plans (Venture Minerals) Mount Lindsay Tin Mine Plans (Venture Minerals)

.

“The Mount Lindsay mine is a Pilbara style open cut super pit that will devastate a large area of the Tarkine rainforest wilderness within an existing reserve. The 3.5 x 3km disturbance area is the equivalent of 420 Melbourne Cricket Grounds and a 220m depth being over twice the height of the Sydney Harbour Bridge,” said Tarkine National Coalition spokesperson Scott Jordan.

“It is completely inconsistent with the protection of the Tarkine, and Minister Burke must act immediately to ensure that the Tarkine has the highest level of protection going into this assessment.”

[Source: ‘Mine plan prompts new Emergency National Heritage bid for Tarkine’, by Scott Jordan, Campaign Coordinator Tarkine National Coalition, 20111111, ^http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php/article/mine-plan-prompts-new-emergency-national-heritage-bid-for-tarkine]

. .

Venture Minerals plans to rely on Tasmanian hydro power (probably at a government subsidised discount and so further reducing the power available to Tasmanian residents). Tasmania’s precious natural heritage is pillaged to make West Australian and foreign corporate investors richer.

[Read More: ^ http://www.ventureminerals.com.au/projects_tas.html].

.

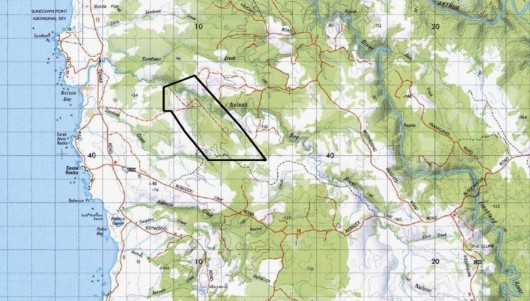

Shree Minerals proposed open-cut mine at Nelson Bay River (2011)

.

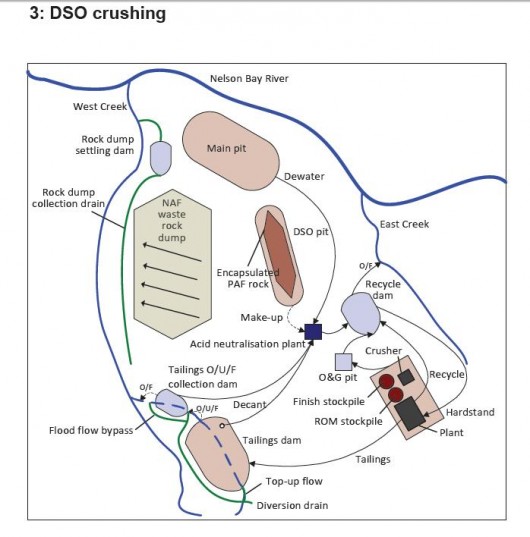

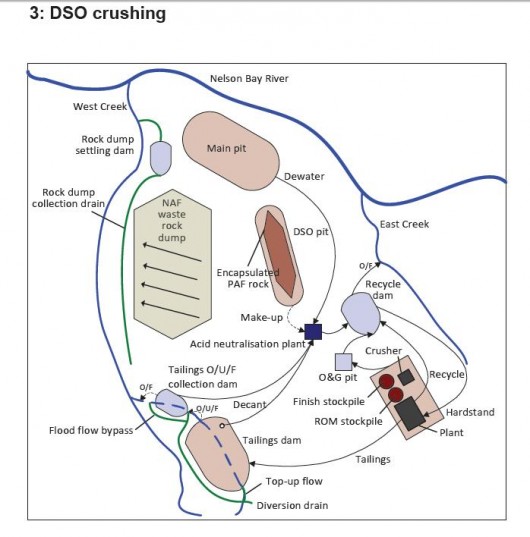

Shree Minerals wants an open cut mine on the upper reaches of Nelson Bay River. According to the Tasmanian Environmental Protection Authority (EPA), Shree Minerals Ltd has proposed to develop an open pit magnetitie/hematite mine and processing plant near Nelson Bay River, approximatley 7 kilometres east of Temma in northwest Tasmania. The proposed mine will target 4 million tonnes of the resource over a 10 year period producing 150,000 tonnes of product per year.

[Source: Tasmanian EPA, ^ http://epa.tas.gov.au/regulation/shree-minerals-ltd-nelson-bay-river-mine [> Read More (PDF, 7MB)]

. Shree Minerals proposed Tin Mine Near Nelson Bay River

..in The Tarkine

(click map to enlarge) Shree Minerals proposed Tin Mine Near Nelson Bay River

..in The Tarkine

(click map to enlarge)

.

Shree Minerals is an Indian company based in Madhya Pradesh in central India [Read More: ^http://www.shreemineralsandfuels.com/] So Tasmania’s precious natural heritage is pillaged to make Indian billionaires richer.

It has found to give scant regard to protecting fragile ecology in The Tarkine. Shree Minerals’ Environmental Impact Statement for the proposed Nelson Bay River open cut iron ore mine as a mismatch of omissions, flawed assumptions and misrepresentations, according to the Tarkine National Coalition.

- Key data on endangered orchids is missing

- Projections on impacts on Tasmanian devil and Spotted tailed quoll are based on flawed and fanciful data

- The EIS produced by the company as part of the Commonwealth environmental assessments has failed to produce a report relating to endangered and critically endangered orchid populations in the vicinity of the proposed open cut mine. The soil borne Mychorizza fungus is highly succeptible to changes in hydrology, and is essential to the germination of the area’s native orchids which cannot exist without Mychorizza. Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke included this report as a requirement in the project’s EIS guidelines issued in June 2011.

- Shree Minerals have avoided producing scientific claiming that its proposed 220 metre deep hole extending 1km long will have no impact on hydrologyor on cthe adjacent Nelson Bay River.

- Data relating to projections of Tasmanian devil roadkill from mine related traffic are flawed. The company has used a January-February traffic surveys as a current traffic baseline which skews the data due to the higher level of tourist, campers and shackowner during the traditional summer holiday season. DIER data indicates that there is a doubling of vehicles on these road sections between October and January. The company also asserted an assumed level of mine related traffic that is substantially lower than their own expert produced Traffic Impact Assessment. The roadkill assumptions were made on an additional 82 vehicles per day in year one, and 34 vehicles per day in years 2-10, while the figures the Traffic Impact Assessment specify 122 vehicles per day in year one, and 89 vehicles per day in ongoing years.“When you apply the expert Traffic Impact Assessment data and the DIER’s data for current road use, the increase in traffic is 329% in year one and 240% in years 2-10 which contradicts the company’s flawed projections of 89% and 34%”. “This increase of traffic will, on the company’s formulae, result in up to 32 devil deaths per year, not the 3 per year in presented in the EIS.”

“Shree Minerals either is too incompetent to understand it’s own expert reports, or they have set out to deliberately mislead the Commonwealth and State environmental assessors.”

.

[Source: ‘Shree Minerals’ Impact Statement documentation critically non-compliant’, by Scott Jordan, Campaign Coordinator Tarkine National Coalition, 20120222, ^http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php/article/shree-minerals-impact-statement-documentation-critically-non-compliant]

.

Nelson Bay River flows through pristine wilderness

Industrial Miners just don’t get it!

[Source: http://www.dpiw.tas.gov.au (Nelson Bay Report on water quality monitoring – >Read Report]

. Nelson Bay River flows through pristine wilderness

Industrial Miners just don’t get it!

[Source: http://www.dpiw.tas.gov.au (Nelson Bay Report on water quality monitoring – >Read Report]

.

In 2011, a visit to the Shree Minerals’ Nelson Bay River proposed mine site in the Arthur Pieman Conservation Area has discovered that the mining company has failed to cap at least nine drill holes, creating risks to the resident population of disease free Tasmanian devils.

Failing to cap drill holes is a serious breach of both the Mineral Exploration Code of Practice and the operating conditions of their Exploration License. If Tasmanian devils are found to have perished in the holes, the company may be in breach of the Threatened Species Protection Act 1995.

Shree Minerals death traps for Tasmanian Devils Shree Minerals death traps for Tasmanian Devils

.

[Source: ‘Call for Moratorium on New Mines in Tasmania. ‘Shree’s deception makes them unfit’’, by Isla MacGregor, Tasmanian Public & Environmental Health Network (TPEHN), 20110930, ^http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php/article/call-for-moratorium-on-new-mines-in-tasmania]

.

Ecological damage from ‘Mineral Exploration’

.

Shree Minerals carving up wilderness across The Tarkine, even before mining commences Shree Minerals carving up wilderness across The Tarkine, even before mining commences

.

Even before actual mining commences, mineral exploration causes its own destructive impacts upon fragile ecosystems:

- New access roads are bulldozed through pristine wilderness to multiple exploration and drilling sites.

- Native vegetation and dependent ecology is destroyed as gridlines are bulldozed

- Fragile top soils are removed

- Soil erosion occurs at drills sites as soon as it rains, and rainfall is particularly intense across western Tasmania

- The eroded soil becomes sediment and chokes and pollutes nearby watercourses and further downstream

- Exposed soils also erode into watercourses, and without topsoil the native vegetation is unable to recover

- Rubbish is dumped

- Spills of chemicals and pollutants from drilling contaminate crystal pure watercourses and permeate into ground water and aquifers

- Spread of pests including plant diseases such as myrtle wilt is exacerbated

- Drill holes into ground water disturb and alter aquifers causing unknown impacts particularly in karst areas, which are prevalent across The Tarkine

.

These impacts are ignored by industrial miners.

Industrial Miners eco-raping the fragile Tarkine

Wam, bam thank you mam! Industrial Miners eco-raping the fragile Tarkine

Wam, bam thank you mam!

.

Tasmania’s Minerals Council – one eyed to pillage

.

The Tasmanian Minerals Council exists so that Tasmania may be mined. Irrespective of what values are on the surface, the Tasmanian Minerals Council sees Tasmania as a quarry to be exploited. If it is not mining Tasmania, or talking about current and planned mines, or encouraging more mining of Tasmania, then it simply isn’t doing its job putting its very existence into question. Its mandate is one eyed.

Just as Forestry Tasmania is the industry driver of logging of Tasmania’s native forests, the Tasmanian Minerals Council is the industry driver of mining Tasmania’s native forests – same destructive outcome, just different type of industrial exploitation. Both are tacit Tasmanian government departments only with corporatised names and structures. See a map of Tasmania through the eyes of the Tasmanian Minerals Council below:

Quarry Map of Tasmania Quarry Map of Tasmania

.

Tasmanian Minerals Council describes itself as “the representative organisation for the exploration, mining and mineral processing industries in Tasmania“. It counts among its members all of the main mines and mineral processing operations. So basically it is the Tasmanian Government’s Department of Mining, but named a ‘council‘ in order to convey a public impression of being an industry body, whereas it is just a policy arm of government.

And the board of directors are all executives employed by industrial miners. They each have vested interests in mining Tasmania for their own company benefits, and collectively to maximise the exploitation of Tasmania for mining. It is cosy chronyism, and accountable to the broader Tasmanian community.

Terry Long

Tasmanian Minerals Council current CEO

Capable of seeing Tasmania only through miner’s subterranean eyes

Terry Long

Tasmanian Minerals Council current CEO

Capable of seeing Tasmania only through miner’s subterranean eyes

“You wouldn’t want to contemplate a Northern Tasmania economy without Temco (an industrial manganese-alloy smelter operation) and Bell Bay Aluminium”

~ Terry Long, 17th March 2012.

[Source: ‘Mining challenges are revealed at forum‘, by Brianna McShane, 20120317, ^http://www.examiner.com.au/news/local/news/general/mining-challenges-are-revealed-at-forum/2491279.aspx]

.

To justify its existence the Tasmanian Minerals Council thinks it and mining Tasmania is very important.

“The minerals industry is the cornerstone of Tasmania’s economy. It is important to the lives of every Tasmanian and brings with it a rich economic and cultural heritage and a capacity to ensure a prosperous future for Tasmania.”

.

The Tasmanian Labor Party (currently in government) and the Tasmanian Liberal Party both see mining as important to Tasmania because of the mining royalty revenue derived by the Tasmanian Government. Of course it is about money.

To be politically correct, the Tasmanian Minerals Council professes a catchphrase: “promoting the development of safe, profitable and sustainable mineral sector operating within Tasmania“. It may be sustainable, but sustainable for industrial miners, not Tasmania’s ecology.

It sees itself playing a role in developing the world’s natural resources to supply the demands of modern society, by digging up more of Tasmania. It says that it recognises modern societal expectations of good environmental management and claims that it is ensuring environmental impacts are minimised. It promises that ongoing problems from old mining operations in Tasmania will be rectified if possible. It talks about following a ‘Code for Environmental Management‘ and about observing a set of principles and encourages continual improvement for environmental performance, and indeed broadened the Code to encompass goals and actions that are more representative of a sustainable development framework.

Wonderful motherhood stuff, except the mining reality across Tasmania is completely different.

2011: Sludge from the Aberfoyle Mine runs into the river at Luina (Savage River National Park)

..in The Tarkine

(Photo by Peter Sims, Fairfax) 2011: Sludge from the Aberfoyle Mine runs into the river at Luina (Savage River National Park)

..in The Tarkine

(Photo by Peter Sims, Fairfax)

.

Tasmania’s infamous Iron Blow Mine

Queenstown’s moonscape legacy of Mount Lyell copper mining

(Photo February 2010 – hardly rehabilitated]

[Source: ^http://www.sauer-thompson.com/junkforcode/archives/2010/02/]

Tasmania’s infamous Iron Blow Mine

Queenstown’s moonscape legacy of Mount Lyell copper mining

(Photo February 2010 – hardly rehabilitated]

[Source: ^http://www.sauer-thompson.com/junkforcode/archives/2010/02/]

.

Queenstown’s sulphuric acid legacy of copper mining

..no plans to rehabilitate the moonscape. Queenstown’s sulphuric acid legacy of copper mining

..no plans to rehabilitate the moonscape.

.

The confluence of the King River and Queen River, a few years ago.

Orange-coloured heavy metal toxins from Queenstown and Mt Lyell copper mining continue to flow into Macquarie Harbour.

No effort is made by the Tasmanian Minerals Council to rehabilitate these wild rivers.

Says the Council: “It was established well before the understandings and knowledge we have now, and the practice we expect today. The legacy from the old surface workings will be carried for a long time..”

And this council want more mines in The Tarkine? The confluence of the King River and Queen River, a few years ago.

Orange-coloured heavy metal toxins from Queenstown and Mt Lyell copper mining continue to flow into Macquarie Harbour.

No effort is made by the Tasmanian Minerals Council to rehabilitate these wild rivers.

Says the Council: “It was established well before the understandings and knowledge we have now, and the practice we expect today. The legacy from the old surface workings will be carried for a long time..”

And this council want more mines in The Tarkine?

‘Past damage caused from mining around Queenstown was a product of its times, although present and future generations live with its legacy. Historical practice is not modern practice. Mt Lyell Mine’s holocaust landscape legacy is testament to a past that did not have the technological knowledge or environmental vision we have today. The economic imperative was the main consideration.’

[Source: A mining propaganda brochure produced by The Tasmanian Mineral Council in 2004 entitled ‘Wilderness, Rivers and Mines – The West Coast Experience‘, ^http://www.tasminerals.com.au/west-coast.pdf]

What has changed? Nothing.

.

Tasmanian Minerals Council – ‘Group-Serving Bias’ Syndrome

.

Head in the ground, the Tasmanian Minerals Council is functionally fixed on the view that Tasmania exists so that it man be mined for profit.

The Tasmanian Minerals Council and its mining fraternity suffer from Group-Serving Bias – the tendency to evaluate ambiguous information in a way beneficial to the interests of miners, while auto-dismissing conservationists’ ecological concerns. They see themselves as unaccountable to the Tasmanian public – only to the government and mining vested interests.

The plethora of evidence showing the mining industries destructive impacts on the natural landscape and irreversible harm caused to wildlife and its habitat are ignored by industrial miners and the Tasmanian Minerals Council. The devastating moonscape and dead river legacies of mining across Tasmania are conveniently dismissed by the Tasmanian Minerals Council as ‘history’.

Those careered into the exploitative cultures of Industrial Logging and Industrial Mining, ignorant of Ecology, fail to respect vital and rare natural values even when immersed in a pristine and rare region like The Tarkine.

Why?

Industrialists during their working lives culturally learn a perception bias to dismiss Nature not as integrated Natural Assets, but as untapped Resources waiting to be exploited and profited for industrial gain.

This is an Industrial World View that emanated out of the Industrial Revolution in early 18th Century Britain. Industrialism has become synonymous with Human Progress and has exponentially grown into what has become known as 20th Century global multinational industrialism. Multinational Industrialism is all about large scale efficient exploitation of resources – Natural or Human in order to maximise self-serving interests. On a local level, this translates into exploitation. The Industrial World View is locally destructive, selfish, arrogant and short-sighted. The Tasmanian Minerals Council continues as a legacy of that time..

Scott Jordan of Tarkine National Coalition at the so-called “rehabilitated” tailings dam at a tin mine in The Tarkine.

.. would mining executives drink this brown toxic, acidic, heavy metal water?

This is the Tasmanian Mineral Council being ‘sustainable‘ – they just don’t get it! Scott Jordan of Tarkine National Coalition at the so-called “rehabilitated” tailings dam at a tin mine in The Tarkine.

.. would mining executives drink this brown toxic, acidic, heavy metal water?

This is the Tasmanian Mineral Council being ‘sustainable‘ – they just don’t get it!

.

Tasmanian Mineral Council’s public image spin-doctoring claims that the Tasmanian mining industry did not have a good history when it came to good environmental management. Environmental awareness began to rise around the world in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Until then, the environmental performance of both industry and individuals was often poor, when measured against today’s standards.

Crap!

The Tasmanian Minerals Council does not recognise The Tarkine. Instead, it sees the west coast of Tasmania being “world famous for its geology and mineralisation and world class mineral deposits lie in an arc of volcanic lavas from Low Rocky Point in Tasmania’s South West, northwards through the great mining areas of Mt Lyell, the Dundas mineral field, Henty, Zeehan mineral field, Renison Bell, Rosebery, Tullah, Que River and Hellyer then eastwards to the Moina mineral field near SheffieldSuper…”

What Tarkine? What forests, where?

This year, the Tasmanian Minerals Council encouraged by the Labor Party’s pro-industrialist, Bryan Green MP, is ramping up mining activity, particularly in The Tarkine. Bryan Green is currently Tasmania’s Deputy Premier and Minister for Primary Industries, Water, Energy, Resources, Local Government, Planning, and Racing.

Bryan Green MP

Tasmania’s current Labor Minister for Resources and Energy, etc

Caught drink driving in June 2011

[Source: ^http://www.themercury.com.au/article/2011/06/26/240875_tasmania-news.html] Bryan Green MP

Tasmania’s current Labor Minister for Resources and Energy, etc

Caught drink driving in June 2011

[Source: ^http://www.themercury.com.au/article/2011/06/26/240875_tasmania-news.html]

.

Bryan Green and Tasmanian Minerals Council are in a froth at present with ‘almost 80 companies spending a record $38.7 million last year looking for the mines of tomorrow’. Drill rigs are humming on many of the 194 exploration licences held by these companies and another 15 licences are pending approval’ – reports the Hobart Mercury newspaper.

Spending on exploration has now rebounded to above pre-global financial crisis levels and several projects have progressed to the point where new mining jobs are on the horizon.

Mining hopefuls are shoring up iron and tin deposits on the West Coast, while others are looking deeper into coal proposals at Fingal and silica projects at Maydena.

Venture Minerals is progressing its iron and iron, tungsten and tin mine at Mount Lindsay outside Burnie and Shree Minerals is working to get its iron ore mine running at Nelson Bay River, in the Tarkine.

Shree Minerals is one of about 20 companies with their eyes set firmly on the mining potential in the Tarkine, as conservationists are working to have the area protected through a Natural Heritage listing. Ultimately, green groups want the area to become a national park, which would stop mining development in its tracks.

At Zeehan, Melbourne-based company Stellar Resources is spending $6 million on a year-long drilling program as it progresses its plans to construct a $108-million tin mine and processing plant.

Stellar Resources chief executive Peter Blight said the company hoped to move into construction in 2014 and start producing tin concentrate in 2015. He said the company was excited by its Heemskirk Tin project which it took on as a solo venture last year.

The area has been investigated for its mineral potential before first by the West Coast’s mining pioneers and more recently by Aberfoyle. When Western Metals took over Aberfoyle, the Zeehan tin project sat in the bottom of a drawer.

But Mr Blight said early drilling and scoping studies looked promising and he expected to be working on financing the project by the end of next year.

Demand for tin continues to increase as the world shuns lead solder. Right now, there is a 70,000-tonne gap between global tin demand and supply.

When developed, the Heemskirk project would produce almost 4000 tonnes of tin concentrate a year and be only the second tin mine in Australia.

The other, Renison Bell, is just 18km away from Zeehan.’

.

[Source: ‘Drill rigs hum in $38m hunt‘, by Helen Kempton, The Mercury (Hobart), 20120416, ^http://www.themercury.com.au/article/2012/04/16/319021_tasmania-news.html]

.

Now Industrial Miners are set to exterminate The Tarkine!

. .

Tags: Cairngorms National Park, Caledonian Forest, Code for Environmental Management, Grand Canyon National Park, Group-Serving Bias, industrial logging, industrial mining, Kahurangi National Park, Mount Lindsay, Myrtle Beech, Orange-bellied Parrot, Savage River Mine, Savage River National Park, Tanjung Puting National Park, Tasmania's Tarkine Wilderness, Tasmanian Devil, Tasmanian Minerals Council, The Tarkine, Venture Minerals, World Heritage

Posted in Tasmanian Devils, Threats from Mining | 3 Comments »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Tuesday, February 28th, 2012

Click above icon to play Pink Floyd’s ‘Wish You Were Here’

..first turn speakers on, then while playing scroll slowly through this article… Click above icon to play Pink Floyd’s ‘Wish You Were Here’

..first turn speakers on, then while playing scroll slowly through this article…

.

..So, so you think you can tell

Heaven from Hell?

Blue skies from pain?

.

Can you tell a green field

From a cold steel rail?

A smile from a veil?

Do you think you can tell?

.

Did they get you to trade

Your heroes for ghosts?

Hot ashes for trees?

Hot air for a cool breeze?

.

Cold comfortable change?

Did you exchange

A walk on part in the war

For a lead role in a cage? …

.

(Lyrics extract from Pink Floyd’s legendary song ‘Wish You Were Here‘ off their 1975 album of the same name)

.

These photos, as you scroll through them, are of Tasmania’s wild old growth forest heritage, which is currently being destroyed in 2012, driven by the Premier Lara Giddings Labor Government of Tasmania.

.

.

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

Australia’s Prime Minister Julia Gillard,

who on 7th August 2011 personally promised the protection of Tasmania’s old growth forests. Australia’s Prime Minister Julia Gillard,

who on 7th August 2011 personally promised the protection of Tasmania’s old growth forests.

.

. .

. .

. .

. .

Click photo to enlarge Click photo to enlarge

.

. .

Tasmania’s disappearing wildlife wish Julia was here

.

. .

. .

[Photo by Editor Sept 2011] [Photo by Editor Sept 2011]

Click photo to enlarge

.

. .

.. ..

.. ..

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

Follow the Tree Sit Protest defending Tasmania’s native forests

^http://observertree.org/ Follow the Tree Sit Protest defending Tasmania’s native forests

^http://observertree.org/

.

.

Monday, February 27th, 2012

This article is by Scott Jordan, Campaign Coordinator Tarkine National Coalition, initially entitled ‘Shree Minerals’ Impact Statement documentation critically non-compliant‘ dated 20120222..

Shree Minerals – foreign miners pillaging Tasmania’s precious Tarkine wilderness

(Photo courtesy of Tarkine National Coalition, click photo to enlarge) Shree Minerals – foreign miners pillaging Tasmania’s precious Tarkine wilderness

(Photo courtesy of Tarkine National Coalition, click photo to enlarge)

.

Tarkine National Coalition has described the Shree Minerals’ Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the proposed Nelson Bay River open cut iron ore mine as a mismatch of omissions, flawed assumptions and misrepresentations.

Key data on endangered orchids is missing,

and projections on impacts on Tasmanian Devil and Spotted-tailed Quoll

are based on flawed and fanciful data.

Spotted-tailed Quoll Spotted-tailed Quoll

.

The EIS produced by the company as part of the Commonwealth environmental assessments has failed to produce a report relating to endangered and critically endangered orchid populations in the vicinity of the proposed open cut mine. The soil borne Mychorizza fungus is highly succeptible to changes in hydrology, and is essential to the germination of the area’s native orchids which cannot exist without Mychorizza. Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke included this report as a requirement in the project’s EIS guidelines issued in June 2011.

Australia’s Minister for Environment

Tony Burke Australia’s Minister for Environment

Tony Burke

.

“Shree Minerals have decided that undertaking the necessary work on the proposal is likely to uncover some inconvenient truths, and so instead of producing scientific reports they are asking us to suspend common sense and accept that a 220 metre deep hole extending 1km long will have no impact on hydrology.” said Tarkine National Coalition spokesperson Scott Jordan.

Utter devastation

A magnetite mine at nearby Savage River Utter devastation

A magnetite mine at nearby Savage River

.

“It’s a ridiculous notion when you consider that the mine depth will be some 170 metres below the level of the adjacent Nelson Bay River.”

TNC has also questioned the company’s motives in the clear contradictions and misrepresentations in the data relating to projections of Tasmanian devil roadkill from mine related traffic. The company has used a January-February traffic surveys as a current traffic baseline which skews the data due to the higher level of tourist, campers and shackowner during the traditional summer holiday season.

Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources (Tasmania) (DIER) data indicates that there is a doubling of vehicles on these road sections between October and January.

The company also asserted an assumed level of mine related traffic that is substantially lower than their own expert produced Traffic Impact Assessment.

The roadkill assumptions were made on an additional 82 vehicles per day in year one, and 34 vehicles per day in years 2-10, while the figures the Traffic Impact Assessment specify 122 vehicles per day in year one, and 89 vehicles per day in ongoing years.

“When you apply the expert Traffic Impact Assessment data and the DIER’s data for current road use, the increase in traffic is 329% in year one and 240% in years 2-10 which contradicts the company’s flawed projections of 89% and 34%”.

“This increase of traffic will, on the company’s formulae, result in up to 32 devil deaths per year, not the 3 per year in presented in the EIS.”

“Shree Minerals either is too incompetent to understand it’s own expert reports, or they have set out to deliberately mislead the Commonwealth and State environmental assessors.”

“Either way, they are unfit to be trusted with a Pilbara style iron ore mine in stronghold of threatened species like the Tarkine.”

The public comment period closed on Monday, and the company now has to compile public comments received and submit them with the EIS to the Commonwealth.

.

. .

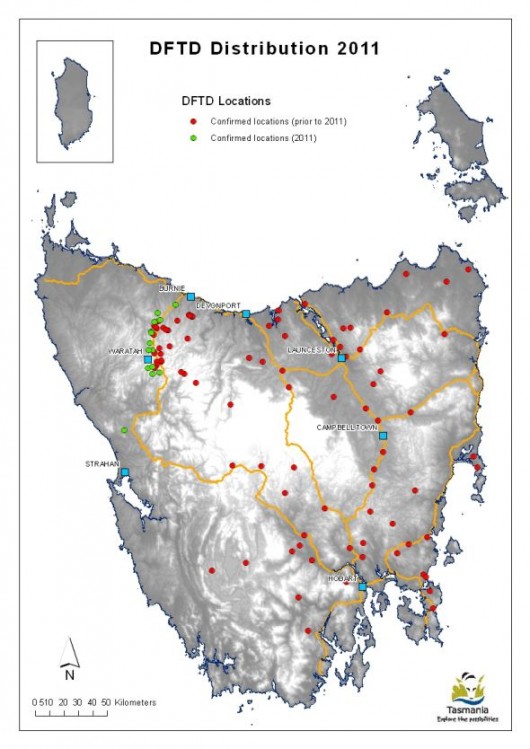

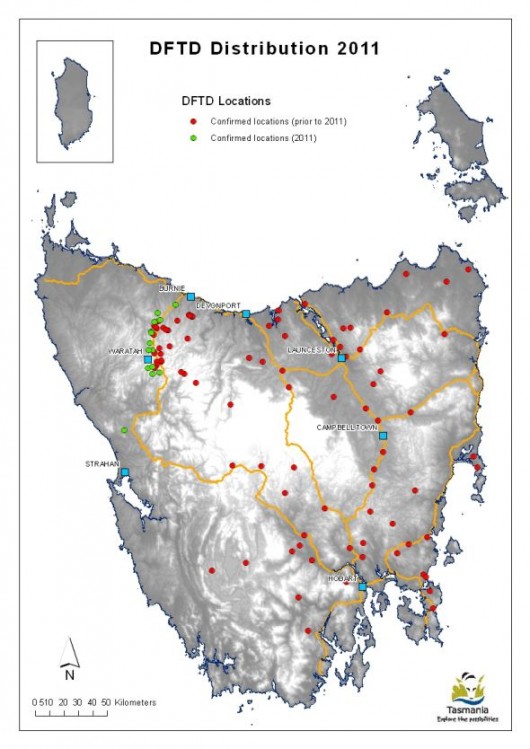

Discovery of Tasmanian devil facial tumour disease in the Tarkine

Media Release 20120224

.

Tarkine National Coalition has described the discovery of Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) at Mt Lindsay in the Tarkine as a tragedy.

“The Tarkine has been for a number of years the last bastion of disease free devils, and news that the disease has been found in the south eastern zone of the Tarkine is devastating news”, said Tarkine National Coalition spokesperson Scott Jordan.

“It is now urgent that the federal and state governments step up and take immediate action to prevent any factors that may exacerbate or accelerate the transmission of this disease to the remaining healthy populations in the Tarkine”.

“The decisions made today will have a critical impact on the survival of the Devil in the wild. Delay is no longer an option – today is the day for action.”

“They should start by reinstating the Emergency National Heritage Listing and placing an immediate halt on all mineral exploration activity in the Tarkine to allow EPBC assessments.”

.

NOTE: EPBC stands for Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

.

.

. .

Proposed Mine Site Plan (Direct Shipping Ore) with flows to enter tributaries of Nelson River

(Source: Shree Minerals EIS, 2011) Proposed Mine Site Plan (Direct Shipping Ore) with flows to enter tributaries of Nelson River

(Source: Shree Minerals EIS, 2011)

.

“The Nelson Bay Iron Ore Project (ELs 41/2004 & 54/2008) covers the Nelson Bay Magnetite deposit with Inferred Mineral Resources reported to Australasian Joint Ore Reserves Committee (JORC) guidelines. Drilling will look to enlarge the deposit and improve the quality of the resource, currently standing at 6.8 Million tonnes @ 38.2% magnetite at a 20% magnetite cut off. In addition exploration work will look follow up recent drilling of near surface iron oxide mineralisation in an attempt delineate direct shipping ore. Exploration of additional magnetic targets will also be undertaken.”

[Source: Shree Minerals website, ^http://www.shreeminerals.com/shreemin/scripts/page.asp?mid=16&pageid=27]

.

The Irreversible Ecological Damage of Long Wall Mining

.

‘Impacts of Longwall Coal Mining on The Environment‘ >Read Report (700kb)

[Source: Total Environment Centre, NSW, 2007, ^http://www.tec.org.au/component/docman/doc_view/201-longwall-rep07]

.

Mining Experience in New South Wales – Waratah Rivulet

[Source: ^http://riverssos.org.au/mining-in-nsw/waratah-rivulet/]

.

The image belows show the shocking damage caused by longwall coal mining to the Waratah Rivulet, which flows into Woronora Dam.

Longwalls have run parallel to and directly under this once pristine waterway in the Woronora Catchment Special Area. You risk an $11,000 fine if you set foot in the Catchment without permission, yet coal companies can cause irreparable damage like this and get away with it.

Waratah Rivulet is a third order stream that is located just to the west of Helensburgh and feeds into the Woronora Dam from the south. Along with its tributaries, it makes up about 29% of the Dam catchment. The Dam provides both the Sutherland Shire and Helensburgh with drinking water. The Rivulet is within the Sydney Catchment Authority managed Woronora Special Area there is no public access without the permission of the SCA. Trespassers are liable to an $11,000 fine.

.

Longwall Mining under Waratah Rivulet

Metropolitan Colliery operates under the Woronora Special Area. Excel Coal operated it until October 2006 when Peabody Energy, the world’s largest coal mining corporation, purchased it. The method of coal extraction is longwall mining. Recent underground operations have taken place and still are taking place directly below the Waratah Rivulet and its catchment area.

In 2005 the NSW Scientific Committee declared longwall mining to be a key threatening process (read report below). The Waratah Rivulet was listed in the declaration along with several other rivers and creeks as being damaged by mining. No threat abatement plan was ever completed.

In September 2006, conservation groups were informed that serious damage to the Waratah Rivulet had taken place. Photographs were provided and an inspection was organised through the Sydney Catchment Authority (SCA) to take place on the 24th of November. On November 23rd, the Total Environment Centre met with Peabody Energy at the mining company’s request. They had heard of our forthcoming inspection and wanted to tell us about their operation and future mining plans. Through a PowerPoint presentation they told us we would be shocked by what we would see and that water had drained from the Rivulet but was reappearing further downstream closer to the dam.

The inspection took place on the 24th of November and was attended by officers from the SCA and the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC), the Total Environment Centre, Colong Foundation, Rivers SOS and two independent experts on upland swamps and sandstone geology. We walked the length of the Rivulet that flows over the longwall panels. Although, similar waterways in the area are flowing healthily, the riverbed was completely dry for much of its length. It had suffered some of the worst cracking we had ever seen as a result of longwall mining. The SCA officers indicated that at one series of pools, water levels had dropped about 3m. We were also told there is anecdotal evidence suggesting the Rivulet has ceased to pass over places never previously known to have stopped flowing.

It appeared that the whole watercourse had tilted to the east as a result of the subsidence and upsidence. Rock ledges that were once flat now sloped. Iron oxide pollution stains were also present. The SCA also told us that they did not know whether water flows were returning further downstream. There was also evidence of failed attempts at remediation with a distinctly different coloured sand having washed out of cracks and now sitting on the dry river bed or in pools.

Also undermined was Flat Rock Swamp at the southernmost extremity of the longwall panels. It is believed to be the main source of water recharge for the Waratah Rivulet. It is highly likely that the swamp has also been damaged and is sitting on a tilt.

TEC has applied under Freedom of Information legislation to the SCA for documents that refer to the damage to the Waratah Rivulet.

During the meeting with Peabody on 23rd November, the company stated its intentions sometime in 2007 to submit a 3A application under the EP&A Act 1974 (NSW) to mine a further 27 longwall panels that will run under the Rivulet and finish under the Woronora Dam storage area.

This is very alarming given the damage that has already occurred to a catchment that provides the Sutherland Shire & Helensburgh with 29% of their drinking water. The dry bed of Waratah Rivulet above the mining area and the stain of iron oxide pollution may be seen clearly through Google Earth.

.

The Bigger Picture

In 2005 Rivers SOS, a coalition of 30 groups, formed with the aim of campaigning for the NSW Government to mandate a safety zone of at least 1km around rivers and creeks threatened by mining in NSW.

The peak environment groups of NSW endorse this position and it forms part of their election policy document.

.

Longwall Mining under or close to Rivers and Streams:

.

Seven major rivers and numerous creeks in NSW have been permanently damaged by mining operations which have been allowed to go too close to, or under, riverbeds. Some rivers are used as channels for saline and acid wastewater pumped out from mines. Many more are under threat. The Minister for Primary Industries, Ian Macdonald, is continuing to approve operations with the Department of Planning and DEC also involved in the process, as are a range of agencies (EPA, Fisheries, DIPNR, SCA, etc.) on an Interagency Review Committee. This group gives recommendations concerning underground mine plans to Ian Macdonald, but has no further say in his final decision. A document recently obtained under FOI by Rivers SOS shows that an independent consultant to the Interagency Committee recommended that mining come no closer than 350m to the Cataract River, yet the Minister approved mining to come within 60m.

The damage involves multiple cracking of river bedrock, ranging from hairline cracks to cracks up to several centimetres wide, causing water loss and pollution as ecotoxic chemicals are leached from the fractured rocks.

.

Aquifers may often be breached.

.

Satisfactory remediation is not possible. In addition, rockfalls along mined river gorges are frequent. The high price of coal and the royalties gained from expanding mines are making it all too tempting for the Government to compromise the integrity of our water catchments and sacrifice natural heritage.

.

Longwall Mining in the Catchments

.

Longwall coal mining is taking place across the catchment areas south of Sydney and is also proposed in the Wyong catchment. Of particular concern is BHP-B’s huge Dendrobium mine which is undermining the Avon and Cordeaux catchments, part of Sydney’s water supply.

A story in the Sydney Morning Herald in January 2005 stated that the SCA were developing a policy for longwall coal mining within the catchments that would be ready by the middle of that year. This policy is yet to materialise.

The SMP approvals process invariably promises remediation and further monitoring. But damage to rivers continues and applications to mine areapproved with little or no significant conditions placed upon the licence.

Remediation involves grouting some cracks but cannot cover all of the cracks, many of which go undetected, in areas where the riverbed is sandy for example.

Sometimes the grout simply washes out of the crack, as is the case in the Waratah Rivulet.

The SCA was established as a result of the 1998 Sydney water crisis. Justice Peter McClellan, who led the subsequent inquiry, determined that a separate catchment management authority with teeth should be created because, as he said “someone should wake up in the morning owning the issue” of adequate management.

An audit of the SCA and the catchments in 1999 found multiple problems including understaffing, the need to interact with so many State agencies, and enormous pressure from developers. Developers in the catchments include mining companies. In spite of government policies such as SEPP 58, stating that development in catchments should have only a “neutral or beneficial effect” on water quality, longwall coal mining in the catchments have been, and are being, approved by the NSW government.

Overidden by the Mining Act 1992, the SCA appears powerless to halt the damage to Sydney’s water supply.

.

Alteration of habitat following subsidence due to longwall mining – key threatening process listing

[Source: ‘Alteration of habitat following subsidence due to longwall mining – key threatening process listing’, Dr Lesley Hughes, ChairpersonScientific Committee, Proposed Gazettal date: 15/07/05, Exhibition period: 15/07/05 – 09/09/05on Department of Environment (NSW) website,^http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/determinations/LongwallMiningKtp.htm]

.

NSW Scientific Committee – final determination

.

The Scientific Committee, established by the Threatened Species Conservation Act, has made a Final Determination to list Alteration of habitat following subsidence due to longwall mining as a KEY THREATENING PROCESS in Schedule 3 of the Act. Listing of key threatening processes is provided for by Part 2 of the Act.

.

The Scientific Committee has found that:

1. Longwall mining occurs in the Northern, Southern and Western Coalfields of NSW. The Northern Coalfields are centred on the Newcastle-Hunter region. The Southern Coalfield lies principally beneath the Woronora, Nepean and Georges River catchments approximately 80-120 km SSW of Sydney. Coalmines in the Western Coalfield occur along the western margin of the Sydney Basin. Virtually all coal mining in the Southern and Western Coalfields is underground mining.

2. Longwall mining involves removing a panel of coal by working a face of up to 300 m in width and up to two km long. Longwall panels are laid side by side with coal pillars, referred to as “chain pillars” separating the adjacent panels. Chain pillars generally vary in width from 20-50 m wide (Holla and Barclay 2000). The roof of the working face is temporarily held up by supports that are repositioned as the mine face advances (Karaman et al. 2001). The roof immediately above the coal seam then collapses into the void (also known as the goaf) and a collapse zone is formed above the extracted area. This zone is highly fractured and permeable and normally extends above the seam to a height of five times the extracted seam thickness (typical extracted seam thickness is approximately 2-3.5 m) (ACARP 2002). Above the collapse zone is a fractured zone where the permeability is increased to a lesser extent than in the collapse zone. The fractured zone extends to a height above the seam of approximately 20 times the seam thickness, though in weaker strata this can be as high as 30 times the seam thickness (ACARP 2002). Above this level, the surface strata will crack as a result of bending strains, with the cracks varying in size according to the level of strain, thickness of the overlying rock stratum and frequency of natural joints or planes of weakness in the strata (Holla and Barclay 2000).

3. The principal surface impact of underground coal mining is subsidence (lowering of the surface above areas that are mined) (Booth et al. 1998, Holla and Barclay 2000). The total subsidence of a surface point consists of two components, active and residual. Active subsidence, which forms 90 to 95% of the total subsidence in most cases, follows the advance of the working face and usually occurs immediately. Residual subsidence is time-dependent and is due to readjustment and compaction within the goaf (Holla and Barclay 2000). Trough-shaped subsidence profiles associated with longwall mining develop tilt between adjacent points that have subsided different amounts.

Maximum ground tilts are developed above the edges of the area of extraction and may be cumulative if more than one seam is worked up to a common boundary. The surface area affected by ground movement is greater than the area worked in the seam (Bell et al. 2000). In the NSW Southern Coalfield, horizontal displacements can extend for more than one kilometre from mine workings (and in extreme cases in excess of three km) (ACARP 2002, 2003), although at these distances, the horizontal movements have little associated tilt or strain. Subsidence at a surface point is due not only to mining in the panel directly below the point, but also to mining in the adjacent panels. It is not uncommon for mining in each panel to take a year or so and therefore a point on the surface may continue to experience residual subsidence for several years (Holla and Barclay 2000).

4. The degree of subsidence resulting from a particular mining activity depends on a number of site specific factors. Factors that affect subsidence include the design of the mine, the thickness of the coal seam being extracted, the width of the chain pillars, the ratio of the depth of overburden to the longwall panel width and the nature of the overlying strata; sandstones are known to subside less than other substrates such as shales. Subsidence is also dependent on topography, being more evident in hilly terrain than in flat or gently undulating areas (Elsworth and Liu 1995, Holla 1997, Holla and Barclay 2000, ACARP 2001). The extent and width of surface cracking over and within the vicinity of the mined goaf will also decrease with an increased depth of mining (Elsworth and Liu 1995).

5. Longwall mining can accelerate the natural process of ‘valley bulging’ (ACARP 2001, 2002). This phenomenon is indicated by an irregular upward spike in an otherwise smooth subsidence profile, generally co-inciding with the base of the valley. The spike represents a reduced amount of subsidence, known as ‘upsidence’, in the base and sides of the valley and is generally coupled with the horizontal closure of the valley sides (ACARP 2001, 2002). In most cases, the upsidence effects extend outside the valley and include the immediate cliff lines and ground beyond them (ACARP 2002).

6. Mining subsidence is frequently associated with cracking of valley floors and creeklines and with subsequent effects on surface and groundwater hydrology (Booth et al. 1998, Holla and Barclay 2000, ACARP 2001, 2002, 2003). Subsidence-induced cracks occurring beneath a stream or other surface water body may result in the loss of water to near-surface groundwater flows.

If the water body is located in an area where the coal seam is less than approximately 100-120 m below the surface, longwall mining can cause the water body to lose flow permanently. If the coal seam is deeper than approximately 150 m, the water loss may be temporary unless the area is affected by severe geological disturbances such as strong faulting. In the majority of cases, surface waters lost to the sub-surface re-emerge downstream. The ability of the water body to recover is dependent on the width of the crack, the surface gradient, the substrate composition and the presence of organic matter. An already-reduced flow rate due to drought conditions or an upstream dam or weir will increase the impact of water loss through cracking. The potential for closure of surface cracks is improved at sites with a low surface gradient although even temporary cracking, leading to loss of flow, may have long-term effects on ecological function in localised areas. The steeper the gradient, the more likely that any solids transported by water flow will be moved downstream allowing the void to remain open and the potential loss of flows to the subsurface to continue.

A lack of thick alluvium in the streambed may also prolong stream dewatering (by at least 13 years, in one case study in West Virginia, Gill 2000).

Impacts on the flows of ephemeral creeks are likely to be greater than those on permanent creeks (Holla and Barclay 2000). Cracking and subsequent water loss can result in permanent changes to riparian community structure and composition.

7. Subsidence can also cause decreased stability of slopes and escarpments, contamination of groundwater by acid drainage, increased sedimentation, bank instability and loss, creation or alteration of riffle and pool sequences, changes to flood behaviour, increased rates of erosion with associated turbidity impacts, and deterioration of water quality due to a reduction in dissolved oxygen and to increased salinity, iron oxides, manganese, and electrical conductivity (Booth et al. 1998, Booth and Bertsch 1999, Sidle et al. 2000, DLWC 2001, Gill 2000, Stout 2003). Displacement of flows may occur where water from mine workings is discharged at a point or seepage zone remote from the stream, and in some cases, into a completely different catchment. Where subsidence cracks allow surface water to mix with subsurface water, the resulting mixture may have altered chemical properties. The occurrence of iron precipitate and iron-oxidising bacteria is particularly evident in rivers where surface cracking has occurred. These bacteria commonly occur in Hawkesbury Sandstone areas, where seepage through the rock is often rich in iron compounds (Jones and Clark 1991) and are able to grow in water lacking dissolved oxygen. Where the bacteria grow as thick mats they reduce interstitial habitat, clog streams and reduce available food (DIPNR 2003). Loss of native plants and animals may occur directly via iron toxicity, or indirectly via smothering. Long-term studies in the United States indicate that reductions in diversity and abundance of aquatic invertebrates occur in streams in the vicinity of longwall mining and these effects may still be evident 12 years after mining (Stout 2003, 2004).

8. The extraction of coal and the subsequent cracking of strata surrounding the goaf may liberate methane, carbon dioxide and other gases. Most of the gas is removed by the ventilation system of the mine but some gas remains within the goaf areas. Gases tend to diffuse upwards through any cracks occurring in the strata and be emitted from the surface (ACARP 2001). Gas emissions can result in localised plant death as anaerobic conditions are created within the soil (Everett et al. 1998).

9. Subsidence due to longwall mining can destabilise cliff-lines and increase the probability of localised rockfalls and cliff collapse (Holla and Barclay 2000, ACARP 2001, 2002). This has occurred in the Western Coalfield and in some areas of the Southern Coalfield (ACARP 2001). These rockfalls have generally occurred within months of the cliffline being undermined but in some cases up to 18 years after surface cracking first became visible following mining (ACARP 2001). Changes to cliff-line topography may result in an alteration to the environment of overhangs and blowouts. These changes may result in the loss of roosts for bats and nest sites for cliff-nesting birds.

10. Damage to some creek systems in the Hunter Valley has been associated with subsidence due to longwall mining. Affected creeks include Eui Creek, Wambo Creek, Bowmans Creek, Fishery Creek and Black Creek (Dept of Sustainable Natural Resources 2003, in lit.). Damage has occurred as a result of loss of stability, with consequent release of sediment into the downstream environment, loss of stream flow, death of fringing vegetation, and release of iron rich and occasionally highly acidic leachate. In the Southern Coalfields substantial surface cracking has occurred in watercourses within the Upper Nepean, Avon, Cordeaux, Cataract, Bargo, Georges and Woronora catchments, including Flying Fox Creek, Wongawilli Creek, Native Dog Creek and Waratah Rivulet. The usual sequence of events has been subsidence-induced cracking within the streambed, followed by significant dewatering of permanent pools and in some cases complete absence of surface flow.

11. The most widely publicised subsidence event in the Southern Coalfields was the cracking of the Cataract riverbed downstream of the Broughtons Pass Weir to the confluence of the Nepean River. Mining in the vicinity began in 1988 with five longwall panels having faces of 110 m that were widened in 1992 to 155 m. In 1994, the river downstream of the longwall mining operations dried up (ACARP 2001, 2002). Water that re-emerged downstream was notably deoxygenated and heavily contaminated with iron deposits; no aquatic life was found in these areas (Everett et al. 1998). In 1998, a Mining Wardens Court Hearing concluded that 80% of the drying of the Cataract River was due to longwall mining operations, with the balance attributed to reduced flows regulated by Sydney Water. Reduction of the surface river flow was accompanied by release of gas, fish kills, iron bacteria mats, and deterioration of water quality and instream habitat. Periodic drying of the river has continued, with cessation of flow recorded on over 20 occasions between June 1999 and October 2002 (DIPNR 2003). At one site, the ‘Bubble Pool”, localised water loss up to 4 ML/day has been recorded (DIPNR 2003).

Piezometers indicated that there was an unusually high permeability in the sandstone, indicating widespread bedrock fracturing (DIPNR 2003). High gas emissions within and around areas of dead vegetation on the banks of the river have been observed and it is likely that this dieback is related to the generation of anoxic conditions in the soil as the migrating gas is oxidised (Everett et al. 1998). An attempt to rectify the cracking by grouting of the most severe crack in 1999 was only partially successful (AWT 2000). In 2001, water in the Cataract River was still highly coloured, flammable gas was still being released and flow losses of about 50% (3-3.5 ML/day) still occurring (DLWC 2001). Environmental flow releases of 1.75 ML/day in the Cataract River released from Broughtons Pass Weir were not considered enough to keep the river flowing or to maintain acceptable water quality (DIPNR 2003).

12. Subsidence associated with longwall mining has contributed to adverse effects (see below) on upland swamps. These effects have been examined in most detail on the Woronora Plateau (e.g. Young 1982, Gibbins 2003, Sydney Catchment Authority, in lit.), although functionally similar swamps exist in the Blue Mountains and on Newnes Plateau and are likely to be affected by the same processes. These swamps occur in the headwaters of the Woronora River and O’Hares Creek, both major tributaries of the Georges River, as well as major tributaries of the Nepean River, including the Cataract and Cordeaux Rivers. The swamps are exceptionally species rich with up to 70 plant species in 15 m2 (Keith and Myerscough 1993) and are habitats of particular conservation significance for their biota. The swamps occur on sandstone in valleys with slopes usually less than ten degrees in areas of shallow, impervious substrate formed by either the bedrock or clay horizons (Young and Young 1988). The low gradient, low discharge streams cannot effectively flush sediment so they lack continuous open channels and water is held in a perched water table. The swamps act as water filters, releasing water slowly to downstream creek systems thus acting to regulate water quality and flows from the upper catchment areas (Young and Young 1988).

13. Upland swamps on the Woronora Plateau are characterised by ti-tree thicket, cyperoid heath, sedgeland, restioid heath and Banksia thicket with the primary floristic variation being related to soil moisture and fertility (Young 1986, Keith and Myerscough 1993). Related swamp systems occur in the upper Blue Mountains including the Blue Mountains Sedge Swamps (also known as hanging swamps) which occur on steep valley sides below an outcropping claystone substratum and the Newnes Plateau Shrub Swamps and Coxs River Swamps which are also hydrologically dependent on the continuance of specific topographic and geological conditions (Keith and Benson 1988, Benson and Keith 1990). The swamps are subject to recurring drying and wetting, fires, erosion and partial flushing of the sediments (Young 1982, Keith 1991). The conversion of perched water table flows into subsurface flows through voids, as a result of mining-induced subsidence may significantly affect the water balance of upland swamps (eg Young and Wray 2000). The scale of this impact is currently unknown, however, changes in vegetation may not occur immediately. Over time, areas of altered hydrological regime may experience a modification to the vegetation community present, with species being favoured that prefer the new conditions. The timeframe of these changes is likely to be long-term. While subsidence may be detected and monitored within months of a mining operation, displacement of susceptible species by those suited to altered conditions is likely to extend over years to decades as the vegetation equilibrates to the new hydrological regime (Keith 1991, NPWS 2001). These impacts will be exacerbated in periods of low flow. Mine subsidence may be followed by severe and rapid erosion where warping of the swamp surface results in altered flows and surface cracking creates nick-points (Young 1982). Fire regimes may also be altered, as dried peaty soils become oxidised and potentially flammable (Sydney Catchment Authority, in lit.) (Kodela et al. 2001).

14. The upland swamps of the Woronora Plateau and the hanging swamps of the Blue Mountains provide habitat for a range of fauna including birds, reptiles and frogs. Reliance of fauna on the swamps increases during low rainfall periods. A range of threatened fauna including the Blue Mountains Water Skink, Eulamprus leuraensis, the Giant Dragonfly, Petalura gigantea, the Giant Burrowing Frog, Heleioporus australiacus, the Red-crowned Toadlet, Pseudophryne australis, the Stuttering Frog Mixophyes balbus and Littlejohn’s Tree Frog, Litoria littlejohni, are known to use the swamps as habitat. Of these species, the frogs are likely to suffer the greatest impacts as a result of hydrological change in the swamps because of their reliance on the water within these areas either as foraging or breeding habitat. Plant species such as Persoonia acerosa, Pultenaea glabra, P. aristata and Acacia baueri ssp. aspera are often recorded in close proximity to the swamps.

Cliffline species such as Epacris hamiltonii and Apatophyllum constablei that rely on surface or subsurface water may also be affected by hydrological impacts on upland swamps, as well as accelerated cliff collapse associated with longwall mining.

15. Flora and fauna may also be affected by activities associated with longwall mining in addition to the direct impacts of subsidence. These activities include clearing of native vegetation and removal of bush rock for surface facilities such as roads and coal wash emplacement and discharge of mine water into swamps and streams. Weed invasion, erosion and siltation may occur following vegetation clearing or enrichment by mine water. Clearing of native vegetation, Bushrock removal, Invasion of native plant communities by exotic perennial grasses and Alteration to the natural flow regimes of rivers and streams and their floodplains and wetlands are listed as Key Threatening Processes under the Threatened Species Conservation Act (1995).

.

The following threatened species and ecological communities are known to occur in areas affected by subsidence due to longwall mining and their habitats are likely to be altered by subsidence and mining-associated activities:

Endangered Species

- Epacris hamiltonii a shrub

- Eulamprus leuraensis Blue Mountains Water Skink

- Hoplocephalus bungaroides Broad-headed Snake