Vet kills injured wildlife for convenience

Friday, April 13th, 2012 A Crimson Rosella (juvenile green plumage)

(Platycercus elegans)

(click photo to enlarge)

A Crimson Rosella (juvenile green plumage)

(Platycercus elegans)

(click photo to enlarge)

.

Yesterday was the centenary of the sinking of the Titanic which caused the deaths of 1,514 people at sea. Last week was Easter. I am not a religious person, but it is a time of death on the Christian calendar and supposedly a time for resurrection or rebirth.

One morning just before Easter, I went out into the backyard and heard a bird chirping; not unusual as we have many birds in the Blue Mountains. But the chirping was excited and at ground level coming from the other side of the neighbour’s fence. I peered over and there he was, a juvenile Crimson Rosella, on the ground in a small depression hobbling around trying to get out.

I knew he was a juvenile because he still had his green winged plumage, whereas adult Crimson Rosellas are a magnificent blue and crimson only. I knew he was male because he was a large bird, distinctively larger than many Rosellas. I knew ‘him’, because being large and distinctive from most others, I had noticed him over recent months in our backyard and taking advantage of our bird feeders. He had become a regular and growing into an adult.

A Crimson Rosella (mature)

[Source: ^http://birdsinbackyards.net/species/Platycercus-elegans]

A Crimson Rosella (mature)

[Source: ^http://birdsinbackyards.net/species/Platycercus-elegans]

.

Rightly or wrongly we have a bird feeder (or two) and encourage the native birds into our backyard by both having planted many trees and by providing bird seed in bird feeders. We see Crimson Rosellas (which are parrots), King Parrots and Sulphur-Crested Cockatoos.

Sulphur-crested Cockatoo – a regular in our backyard and apple tree

Sulphur-crested Cockatoo – a regular in our backyard and apple tree

The neighbours were not home, so I grabbed a small cage and put gloves on and went next door to collect the injured Crimson Rosella to take him to the local vet. When I got close, he chirped frightenedly and tried to evade capture, but he was stuck in the small depression and he could only use one leg. For some reason he could not fly away, but I couldn’t see anything wrong with his wings. They were folded up on the normal way.

I carefully picked him up and put him in the cage and covered the cage with a towel to quieten him down. I knew to do this because I am a member of Blue Mountains WIRES (Blue Mountains Wildlife Information, Rescue and Education Service. I brought the cage inside, placed it carefully on the floor and phoned the rescue hotline. The bird was happily trying to get out hanging on to the side of the cage. He seemed happy enough; just needing some expert attention to his leg.

Australian King Parrot

(Alisterus scapularis)

Australian King Parrot

(Alisterus scapularis)

.

I phoned WIRES’ hotline and they advised me to take the Rosella to the local veterinary clinic, as this particular vet was registered with WIRES for caring for injured wildlife.

I placed the cage carefully in the car and drove straight to the vet.

Local Vet

Local Vet.

When I arrived, I asked if there was a fee, as I was happy to pay for their services. I had $150 cash in my pocket just in case. The receptionist explained that there was no charge and that they would examine the leg, X-ray it and keep the bird at the clinic, then contact a WIRES carer to take the bird for rehabiliation until it was fit to return to the wild. I explained that I would contact them the next day to see how the bird was coming along. They gave me my cage back and I returned home.

The next morning I phoned the vet as soon as they opened and asked after the Crimson Rosella. Another receptionist answered the phone. She told me that they had received four Crimson Rosellas yesterday and that three had been euthanized (killed).

I couldn’t believe it. I asked specifically about the large green juvenile that I had brought in with only an injured left leg. She said yes that was one of the parrots that they had euthanized. She gave me some spiel about psitacosis, (parrot beak and feather disease) and then about Crimson Rosellas not being a threatened species anyway.

I said that the bird was quite healthy and vibrant and only had an injured left leg. The bird was not x-rayed and probably not even tested for psitacosis. It was convenient to the vet to just kill the wild birds. I assume the previous receoptionist had not ven xplained that I was happy to pay for the treatment/surgery/whatever to the Crimson Rosella that I had rescued and brought in for care.

I hung up. I felt terrible and empty. That bird had entrusted me, yet I had facilitated it’s killing by taking it to this vet, not to be looked after, but to be killed. This vet played at god. I have lost trust in this vet.

Garbage skip at rear of vet

Garbage skip at rear of vet

.

This is the Veterinarian Oath

.

“Being admitted to the profession of Veterinary medicine, I solemnly swear to use my scientific knowledge and skills for the benefit of society through the protection of animal health, the relief of animal suffering, the conservation of livestock resources, the promotion of public health, and the advancement of medical knowledge.

I will practice my profession conscientiously, with dignity and in keeping with the principles of veterinary medical ethics. I accept as a lifelong obligation, the continual improvement of my professional knowledge and competence.”

.

[Source: ^http://www.equivetaustralia.com/staff.html]

.

Clearly a lesser ethical standard applies to animals in comparison to humans under the more stringent Hypocratic Oath…

.

Hypocratic Oath (Modern Version)

“I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant:

I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those physicians in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.

I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism.

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.

I will not be ashamed to say “I know not”, nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient’s recovery.

I will respect the privacy of my patients, for their problems are not disclosed to me that the world may know. Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given to me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty.

Above all, I must not play at God.

I will remember that I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being, whose illness may affect the person’s family and economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems, if I am to care adequately for the sick.

I will prevent disease whenever I can, for prevention is preferable to cure.

I will remember that I remain a member of society with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.

If I do not violate this oath, may I enjoy life and art, be respected while I live and remembered with affection thereafter. May I always act so as to preserve the finest traditions of my calling and may I long experience the joy of healing those who seek my help.”

.

[Source: Hypocratic Oath, 1964, by Dr. Louis Lasagna, former Principal of the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences and Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University, ^http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/hippocratic-oath-today.html]

Read Also: Australian Medical Association Code of Ethics [Read Code]

.

But we do play at god, us humans. We can kill and justify it – birds, animals, other people, for convenience or choice excuse.

Life is very precious and it doesn’t matter whose life it is. Some religions believe in reincarnations and afterlife. But to those living we only are sure of the life we have now. It can end so soon. Life is so short when one looks back on how quickly it seems to have gone.

Those people on the Titanic who died in the freezing waters shouldn’t have. A few people in charge were playing god recklessly with their lives. Once a life is gone, it can’t be brought back.

Also on the day of the centenary of the Titanic’s sinking, as it happens, a close friend of ours passed away from a brain tumor. We had only just seen him in the hospice a few days prior, very aware that it was going to be the last time we would ever see him. He died on 12th April 2012, coincidently exactly one hundred years after the Titanic sank. He was just 47 and has left a family behind to fend for themselves fatherless, husbandless. It is no-one’s fault per se. Sometimes fate deals randomly to those just going about their lives. It doesn’t make it right. Life is so precious but we perhaps take it for granted, especially when we are young , so full of beans and have so much to look forward to.

.

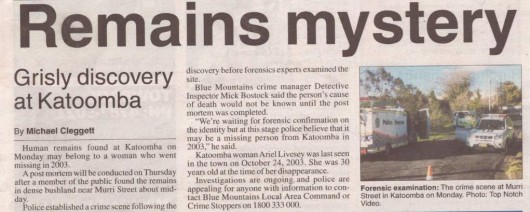

Then, after we returned from visiting our friend in the hospice a few days prior, we returned home to find police and forensic officers in ‘The Gully’ nearby. What was going on?

The police said nothing, but human remains were being gathered from bushland. The following article sheds some light on the tragic find, but not all is yet known at the time of writing.

Yesterday, a retired Presbyterian minister and I went to inspect the site. We wanted to understand the death. The Gully has always felt to be a happy place. We both felt a sense of sadness about the circumstances of the death.

Blue Mountains Gazette 20120411, p.1

Blue Mountains Gazette 20120411, p.1.

It was just a clearing in dense bushland. But there seemed a feeling not of foul play, just of sadness, that a young woman had lost her life there. It is a calm sheltered spot with dappled sunlight through the trees. The minister said a prayer. It had been a sad Easter.

Dappled sunlight in a native forest in Ireland

(Photo by Editor)

Dappled sunlight in a native forest in Ireland

(Photo by Editor)

.

‘The village still haunted by its Titanic loss’

[Source: ‘The village still haunted by its Titanic loss‘, by Sarah Rainey, The Telegraph (UK) – History (tab), 20120411, ^http://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/titanic-anniversary/9195690/The-village-still-haunted-by-its-Titanic-loss.html] Addergoole cemetery, Lahardane

County Mayo, Ireland.

For years, locals refused to talk about the tragedy; now it is marked every year by bell-ringing

Photo: Kim Haunton

Addergoole cemetery, Lahardane

County Mayo, Ireland.

For years, locals refused to talk about the tragedy; now it is marked every year by bell-ringing

Photo: Kim Haunton

.

‘High on the hills above the tiny village of Lahardane in County Mayo, a wooden cross juts from a mound of earth towards the sky. The cross sways back and forth, creaking as gales blow across the valley, through what locals call the “Windy Gap”. As I look towards the village on this April morning, a fine mist has settled low on the hillside.

Little has changed in a hundred years. It was from here, in the shadow of the distant crags of Nephin mountain, that the group known as the Addergoole Fourteen had a last glimpse of home as they made the long journey to board the RMS Titanic. Three men and 11 women left the parish of Addergoole that spring morning in 1912. They travelled 19 miles on foot to the nearest station, where they caught a train to Queenstown, County Cork, 16 hours away. There, they joined 111 other passengers who boarded the Titanic in Ireland, a day after it started its maiden voyage from Southampton.

Seventeen-year-old Annie McGowan was accompanying her aunt Catherine to Chicago. In a letter to relatives, she wrote: “I am coming to America on the nicest ship in the world.” Delia McDermott, 31, was moving to Missouri to work as a housemaid. Before she left, her mother bought her a new hat and gloves, so she would “look like a lady” when the Titanic docked in New York.

Four days later, 11 of the Addergoole Fourteen were dead; their bodies lost at sea. Although the remaining three survived, none returned to live in Ireland. The impact on Lahardane was unique: proportionately more people from this tiny village lost their lives on the Titanic than anywhere else in the world. In a population of 200, 11 deaths was more than a tragedy. It ripped the heart out of the community.

For years, locals refused to talk about the Titanic. All this changed in 2002, when villagers started to hold a bell-ringing ceremony, marking the time the Titanic sank into the Atlantic. Every year, at 2.20am on April 15, relatives of the victims chime the church bell – 11 mournful rings followed by three joyous rings – paying their respects to those who never returned.

This year, things are different in Lahardane. As the village prepares to mark 100 years since the tragedy, locals have started to talk publicly about the impact it had on their families’ lives. For the story of the disaster, once too painful to remember, has become Lahardane’s biggest attraction. Tourists are flocking to the remote spot, now signposted “Ireland’s Titanic village”, to learn more about the untold stories of locals on board the ship.

Bridget Donohue was 21 when she left her job in McHale’s shop to set sail for New York. Her third-class ticket cost £7 15s, equivalent to six months’ wages. Before she left, Bridget asked Maura McHale, the seven-year-old daughter of the shop’s owner, if she would like a gift from America. “I’d like a ring,” Maura replied. Bridget measured the girl’s finger with a piece of string, which she put in her pocket and carried on board. Months later, Maura couldn’t understand why she hadn’t received the ring.

Bridget’s nephew, Davie Donoghue, 80 this year, still lives in Lahardane. He is reluctant to talk about the Titanic. “It was five weeks before my father knew his sister had drowned,” he explains. “Her name was printed wrongly in the passenger log – it was down as ‘Burt’, instead of Bridget. They thought she was still alive. Losing her was very emotional.”

McHale’s corner shop, where Bridget worked, is getting a fresh coat of paint this week, along with other buildings that are enjoying a makeover before April 15. A cultural week, with historical re-enactments, has been planned in the village. There’s a new gift shop and a Titanic memorial park with a bronze sculpture shaped like the ship’s bow.

“It only took them 100 years to do the place up,” jokes Donoghue. As one resident says, the “boreens” (narrow tracks) around here don’t know what’s hit them: the past month has seen reporters from as far afield as New York, and television trucks from Brazil and France, trundling through the Windy Gap.

But, behind the Titanic hype, there remains a muted sense of grief; a respect for dead relatives never known. Since childhood, many locals have picked up snippets about the Titanic. They describe listening in at closed doors as older generations grieved.

Vincent O’Callaghan never knew his great aunt, Delia Mahon, who was 20 when she boarded the ship. “I remember my Nana Kate, her sister, crying about it,” he recalls. He treasures a handful of photographs, showing Nana Kate sitting astride a fence with no shoes on. Sadly, there are none of Delia. He has just one memento of his great aunt, from the passenger logs of April 1912: “Miss Bridget Delia Mahon, Ticket No: 330924, Destination: 438 Franklin Avenue, New York”.

According to survivors, Delia was helped into a lifeboat by her neighbour Patrick Canavan, who found a ladder leading from steerage to the upper decks. First, she had to be coaxed out of a cupboard, where she had hidden when she heard the ship was going down. O’Callaghan, 54, says it can be hard to separate fact from folklore. “I’ve heard that her brother Pat read her tea leaves at a party before she left. They spelt out that there would be an accident on the way to America. Delia got angry when Pat told her not to go.”

For local historian Michael Molloy, this anniversary is a chance to learn about the village’s past. “In the early 20th century, around 30,000 Irish emigrants a year left the country to escape extreme poverty,” he explains. The Titanic was one of many such opportunities – the archives of the local Connaught Telegraph show a list of cross-Atlantic liners offering tickets.

As a child, Molloy met Annie Kate Kelly, one of three Addergoole passengers who escaped the Titanic. She became a nun in Michigan but returned home in the 1950s to visit her family. She flew to Ireland – none of the local survivors would travel by ship again. Annie Kate’s memories of what happened on the ship have become symbolic to the residents of Lahardane, who used her account to commission a stained-glass memorial window for St Patrick’s Church.

Inside the church, sunlight streams through the coloured panes, casting a kaleidoscopic glow over the pews. The scene, entitled “Titanic Rescue”, shows a small girl being lowered from the ship in Lifeboat 16. She looks up at grief-stricken figures on the deck above, wailing and clutching rosary beads as they pray to be saved.

Little else is known about the Addergoole group’s final hours on the Titanic. April 14 was 22-year-old Nora Fleming’s birthday, and a survivor from nearby County Sligo remembers hearing singing and dancing down in third class. Nora, she recalls, was a beautiful singer. They may still have been celebrating at 11.40pm, when the ship collided with the iceberg – and perhaps even at 12.05am, when the first lifeboats were lowered. Nora’s nephew, 71-year-old John Lynn, says her loss left his mother devastated. “She never talked about it; not to the day she died.”

Nora’s relatives waited weeks for confirmation from White Star Line, the company that owned the Titanic, that she had drowned. Her name still appears incorrectly in the passenger lists as Norah Hemming.

This centenary year, members of the Addergoole Titanic Society will gather by candlelight in the small churchyard. They will ring the bell and lay a wreath, before heading to nearby Murphy’s pub to share stories until sunrise. One bell-ringer is Willie Cussack, 78, the second-cousin of Annie McGowan. It was Cussack’s uncle Peter who took Annie and her aunt Catherine to the railway station at the start of their journey to America. Annie survived the tragedy but Catherine, 42, drowned after they became separated.

“When he talked, you could see the sadness in his face; his eyes would well up with tears,” Cussack says of his uncle. For Cussack, the bell-ringing is a particularly poignant tribute to Lahardane’s Titanic victims. Years ago, he remembers hearing a boy crying as he cycled through the Addergoole hills; this is how he imagines the cries of grief in 1912 when locals found out their loved ones had died. For him, this is what the bell-ringing represents.

“Do you know what an echo sounds like in these mountains?” he asks, pointing towards the craggy hills. “The cry is gone and it comes back and it is all around you, all over the village. I can imagine the way it echoed across the bog lands that morning. When we hear the bell ringing in the church, we imagine just a tiny piece of what they went through.

It’s the most haunting sound you will ever hear.”

.

.

Footnote

.

A week after posting this article, the local paper The Blue Mountains Gazette published information about the human remains found in The Gully (20120418, page 3)…