The Gully Plan of 2004 not acted upon by Council

Monday, December 21st, 2020We herein enclose a complete copy of Blue Mountains {city} Council’s 2004 Plan of Management for Upper Kedumba River Valley, which we term The Gully Water Catchment. It was formerly gazetted by Council as Katoomba Falls Creek Valley for decades prior to its unilateral renaming by Council in 1995.

[Editor’s note: We reject the urban assertion by Blue Mountains City Council (BMCC) councillors that the Blue Mountains could or should be in any way labelled as a “city” as if comparable with Sydney. So we choose to place the word {city} in BMCC’s title in brackets.]

The Gully Water Catchment lies on the western edge of the regional township of Katoomba in the Blue Mountains region, located 100km due west of Sydney’s CBD.

The Valley takes that shape of an elongated valley from a natural amphitheatre in the north southward and features various natural riparian zones around watercourses that confluence into a central creek across this section of the Blue Mountains plateau to Katoomba Falls.

The Gully Water Catchment is situated on the Blue Mountains central plateau and covers (290 hectares/2.9 km2) and lies wholly within the watershed ridgeline of Bathurst Road to the north, meandering along the watershed through central Katoomba to the east, the ridgeline along Valley Road to the Jamison clifftop escarpment to the west, and to Katoomba Falls to the south.

The water plunges into the Kedumba River into the Jamison Valley 300m below the Blue Mountains plateau which then flows downstream for about 50km to the artificial Lake Burragorang above Warragamba Dam.

This dam was built in post-WWII from 1948-1960 to provided a fresh water reservoir for an ever-growing Greater Sydney for it’s primary drinking water. Before the construction of the dam, Burragorang Valley had been inhabited by white settlers since the 19th century, and for thousands of years before, the Burragorang valley was part of the tribal lands of the Gundungurra Aboriginal people, who became displaced local Aboriginal refugees in their own country.

In 1948 some fled to squat in the small valley they were familiar and had family connections with, situated about 40 km to the north they nicknamed The Gully on the edge of Katoomba.

The natural sedge swamp within the northern part of The Valley (The Gully), previously referred to as ‘Frank Walford Park’. The sky blue sign with white lettering by the lake across from the derelect Madge Walford Fountain was secretly removed a few years ago (2019?) presumably by Blue Mountains {city} Council.

Katoomba Falls Creek Valley was unilaterally renamed by Blue Mountains {city} Council in its wisdom around 1995 to being renamed ‘Upper Kedumba River Valley‘.

Why the name change? Well, from experience in dealing with Blue Mountains {city} Council in relation to this valley (2002-2007) one suspects that it was part of Council’s relentless ‘divide and conquer strategy’ to undermine then in 1996, what had been a decade long struggle by local resident group Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Inc. (The Friends) to save and protect The Valley from ongoing threats of destructive harm and neglect and to seek a joint co-operative land management between the interested local community and Blue Mountains {city} Council.

The Valley includes the Aboriginal Place (AP) affectionately known by former residents as ‘The Gully’. They were a mix of poor folk, a few dozen or so, who subsisted on the edge of town either renting or squatting in very basic shack-style homes. That is until Blue Mountains {city} Council back in 1957 decided to forcibly evict them all and bulldoze their dwellings to build a motor racing track for an elitist wealthy motor racing fraternity. For many years this northern part of The Valley used to be called Frank Walford Park, after a previous Council mayor.

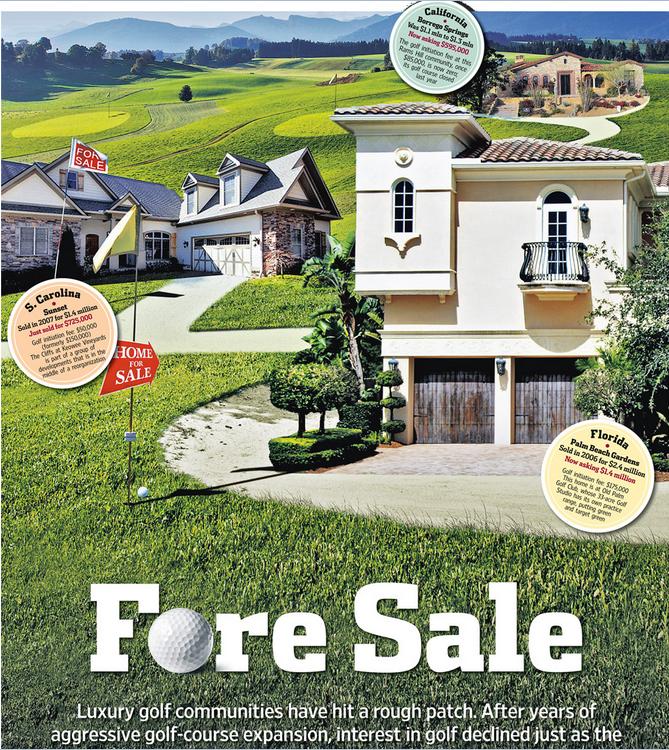

Subsequently over the years since, Blue Mountains {city} Council has incrementally sold off numerous land parcels to private housing development so as to boost its revenue base. The remnant bushland sections are gazetted as ‘Community Land’ under the New South Wales Local Government Act 1993.

Despite The Valley naturally being a riparian zone (mostly wetland) of the creek and its various headwater streams, the community land have become quite separated as Council has unilaterally re-zoned various land parcels on paper from being ‘Community Land‘ to ‘Operational Land‘, invariably in preparation to be flogged off for housing. History records many land sales by Blue Mountains {city} Council throughout The Valley sold by either for private housing, Katoomba Sports and Aquatic Centre and for what is called South Katoomba Rural Fire Service Station.

Beneath the surface, Council dug up the wetland and installed a massive sewer network.

Council’s 2004 Plan of Management (POM) for The Gully

Council had this 2004 POM document initially compiled in draft form in October 2002 by external consultancy, Environmental Partnership, which is off-Mountains based in distant Ultimo in central Sydney. These dudes do urban landscapes, not natural landscapes – so were they an appropriate choice by council? Well, it depends upon the outcomes council wanted to The Gully plan of management back then. Council filed it anyway.

The POM draft was subsequently revised over a two year period and the final document has the rather lengthy bureaucratic title thus: ‘Upper Kedumba River Valley Plans of Management Covering the Community Lands within “The Gully” Aboriginal Place’ (Revised Edition 2004).

Ok, so the names were evolving and former council mayor Frank Walford, who supported the racetrack usurpation of 1957, and by 2004 was getting out of favour with council due to expressed criticism of his namesake in The Gully by the former residents of The Gully. We note that council’s sky blue coloured ‘The Frank Walford Park’ sign also suddenly disappeared in recent years.

So the ‘subject lands’ exclusively described as ‘“The Gully” Aboriginal Place’ are shown in this map on page 6.

The total area of The Gully Aboriginal Place (defined as being of “cultural significance”) are 44 hectares (43.92ha on page 44 to be precise) for Frank Walford Park, plus 14 hectares (13.74 ha on page 58 to be precise) for McRaes Paddock, plus 8 hectares (7.86 ha on page 63 to be precise) for Katoomba Falls Reserve Cascades Section (Selby Street Reserve). So Council’s 2004 definition for the entire area of The Gully Aboriginal Place was 65.52 hectares, to be precise.

This 2004 iteration stipulates three separate plans of management, one for each of the geographic public land sections of The Valley. It excludes the sizeable western side of The Valley referred to as Katoomba Golf Course – which was and still is public land owned by Blue Mountains {city} Council. It also excludes the watercourse and riparian zone to the west between Wellington Street and Stuarts Road in Katoomba, which is at the time was private pastoral land addressed as 21 Stuarts Road.

The public (Community Land) sections of The Valley included in the document, form a natural riparian corridor along Katoomba Falls Creek, they being:

- Frank Walford Park (comprising the northern headwaters of Katoomba Falls Creek)

- McRae’s Paddock (comprising the main centre section of Katoomba Falls Creek)

- Selby Street Reserve (comprising a eastern side tributary to Katoomba Falls Creek which confluences with Katoomba Falls Creek at Maple Grove Park, as well as the sports ovals and the escarpment top riparian zone to the top of Katoomba Falls)

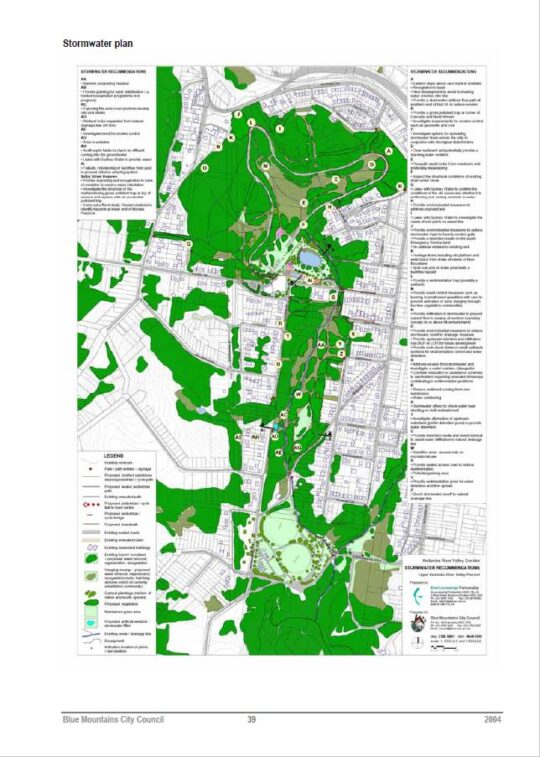

In addition on page 39 of the 2004 Plan of Management there is a 35-point Stormwater Plan for The (entire) Valley.

Council’s Legacy of Planned Inaction for The Valley

These 2004 plans of management (x3) along with the Stormwater Plan were never acted upon by Blue Mountains {city} Council. This is despite the considerable cost of all the research and compilation of preparing the 2004 plans over more than two years, which likely exceeding $100,000.

These plans follow a series of similar plans compiled for this creek valley, which we have on file are:

- (no date) Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study A & B

- (no date) Frank Walford Park – Bushland Management and Report

- 1955: Frank Walford Park Master Plan for Development, 1955 (car racetrack), by Katoomba Municipal Council (Ed: better name)

- c.1980: Draft Assessment of Frank Walford Park, Katoomba – Land Suitability, Environmental Constraints

- 1981: Frank Walford Park Management Plan, by BMCC, 54 pages

- June 1993: Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study – Part 1 Draft Report and Management Plan by F.& J. Bell & Associates, for BMCC, 85 pages

- June 1993: Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study – Part 2 Technical Reporrts, Data and Analysis by F.& J. Bell & Associates, for BMCC, 55 pages

- April 1996: Katoomba Falls Creek Valley – Draft Pan of Management and Report, by Connell Wagner Pty Ltd (consultancy), (for BMCC) approx. 200 pages (inconsistently numbered)

- 3rd July 2000: Upper Kedumba Valley, Katoomba – Report on Cultural Significance…, (for NPWS) by Dianne Johnson with Dawn Colless, 162 pages

- 2001: Area 2 Community Plan (including Katoomba) by Area Community Planning, BMCC, 102 pages

- 2001: Area 2 Sport and Recreation Plan (including Katoomba) by Area Community Planning, BMCC, 107 pages

- 2004: Upper Kedumba River Valley Plans of Management Covering the Community Lands within “The Gully” Aboriginal Place (Revised Edition 2004), by Environment Partnership (consultancy) for BMCC, 105 pages

- August 2005: A Heritage Study of the Gully Aboriginal Place, Katoomba, New South Wales by Allan Lance of heritage Consulting Australia Pty Ltd & NSW Dept Environment and Heritage (for BMCC), 113 pages

- March 2005: Catchment 7 Improvement Grant No.44 Upper Kedumba River Valley, by members of Kedumba Creek Bushcare & BMCC – Final Report for Sydney Catchment Authority, 27 pages

- June 2006: Hawkesbury Nepean River Health Strategy Volume 1, by Hawkesbury Nepean Catchment Management Authority, 78 pages

- June 2006: Hawkesbury Nepean River Health Strategy Volume 2, by Hawkesbury Nepean Catchment Management Authority, 144 pages

- June 2019: The Gully – Stakeholder Engagement Report (June 2019), 44 pages

- 29th September 2021: Proposed Recategorisation of Parts of the Gully Aboriginal Place, Katoomba – Public Hearing and Submissions Final Report, by Parkland Planners for BMCC, 56 pages

- 4th October 2021: The Gully Aboriginal Place Plan of Management, by BMCC, 145 pages.

Not one of the plans above for The Valley has been acted upon by Blue Mountains {city} Council to date since that of 1981. This is disingenous and shameful. It is no wonder that The Friends [1989-2016] became exasperated with Blue Mountains {city} Council and it’s ‘all-talk-no-action‘ recalcitrance on The Valley over the years.

It noteworthy that the chambers of Blue Mountains {city} Council is situated just 200 metres from the eastern ridge top of The Valley’s northern amphitheatre as the crow flies – so close geographically, yet shunned. It seems that since time immemorial nothing’s changed from the time The Valley (Gully) community of struggling ‘have nots’ (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal alike) on this edge of town were shunned by the ‘haves’ uphill of Katoomba and nearby villages.

One would not be surprised if the combined cost of Blue Mountains {city} Council’s compiling of all these plans and reports on The Valley exceeds a million dollars. The funding came from local ratepayers else from grant moneys received from the New South Wales Government. Indeed, one would not be surprised if once each plan was finalised, that Council instantly filed it to gather dust on an archival shelf, such is one’s experience as a former member of the Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Inc.

Copies of the above plans and reports over time we shall publish in The Gully Collection on this website, available for free download and printing to the general public. Access to the ‘The Gully Collection’ is by clicking on The Gully Collection’ photo image on the front page of this website.

Stipulated Plans of Management for Council Community Lands

Under Section 36, of the New South Wales Local Government Act 1993, each local government (local council) throughout New South Wales is legally required to prepare a plan of management for a Community Land area under Council ownership. This means that in the case of the Blue Mountains {city} Council, it is compelled to draft plans of management for each community land area and update these plans from time to time, including the community land within Upper Kedumba River Valley.

Under Section 36 of the Act:

- “A council must prepare a draft plan of management for community land.

- A draft plan of management may apply to one or more areas of community land, except as provided by this Division.

- A plan of management for community land must identify the following:

(a) the category of the land,

(b) the objectives and performance targets of the plan with respect to the land,

(c) the means by which the council proposes to achieve the plan’s objectives and performance targets,

(d) the manner in which the council proposes to assess its performance with respect to the plan’s objectives and performance targets, and may require the prior approval of the council to the carrying out of any specified activity on the land.”

The New South Wales Local Government Act 1993 in fact superseded previous local government Acts that date back to 1919. So the above list where it refers to a plan of management, likely similarly was a required document under the NSW legislation. So the plans of management prepared for Blue Mountains {city} Council have always been mandatory, rather than being some noble gesture by Blue Mountains {city} Council seen to be doing the right civil thing for the local community.

In addition, in the case of selected surviving remnant bushland sections of community land connected with local Aboriginal cultural heritage within the Upper Kedumba River Valley, since 18th May 2002, ‘The Gully’ was declared an Aboriginal Place (AP) by Blue Mountains {city} Council and the NSW Parks Service under Section 84 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW) No 80.

Under Section 72 of National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 No 80 ’72 Preparation of plans of management’ “The Secretary.. (d) may from time to time cause a plan of management to be prepared for any Aboriginal area or wildlife refuge.”

2004 Action Plans not acted upon by Blue Mountains {city} Council

The stipulated Action Plans of the Upper Kedumba River Valley Plans of Management of 2004 were not acted upon by Blue Mountains {city} Council in the intervening seventeen years between 2004 and the current 2021 Plan.

Refer to the supplied copy of the document below – both the Action Table (pages 69-74) and Appendix B (pages 83-94). Council senior management will respond excusing lack of external grant funding (usually from the New South Wales Government), but then they won’t be able to provide any evidence of applying for such funding.

Council simply doesn’t care. It only prepares plans of management because it is legally required to do so under Section 36, of the New South Wales Local Government Act 1993 and also under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 No 80.

Under the latter, Section 79A ‘Lapsing of plans of management‘ stipulates:

“(1) A plan of management for lands reserved under Part 4A expires on the tenth anniversary of the date on which it was adopted unless it is sooner cancelled under this Part.

(2) Not less than 6 months before a plan of management expires, the board of management for the lands concerned must prepare a new plan of management to replace it.

(3) The board of management is to have regard to a plan of management that has expired until the new plan of management comes into effect.”

Blue Mountains {city} Council delayed its review of its 2004 Plan some seventeen years. Not including the NSW bushfire emergency declarations of 2019 and the Coronavirus Pandemic 2020-2021, council’s review process was still an inexcusable five-year delay between the due scheduled review in 2014 and when council initiated community engagement from 4th September 2018.

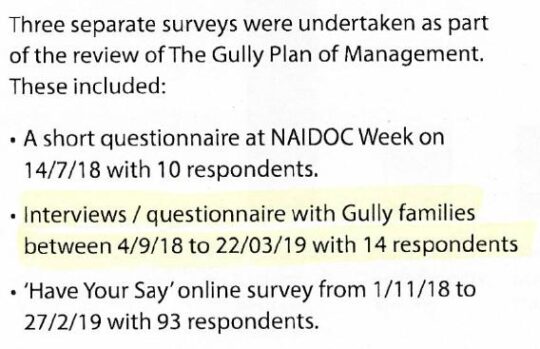

This is evidencial from Blue Mountains {city} Council’s Stakeholder Engagement Report concerning The Gully dated June 2019, page 7 extract as follows:

Extract of Page 7 ‘Methodology’ of Blue Mountains Council’s Stakeholder Engagement Report, June 2019, pre-empting its POM for The Gully 4th October 2021

The image below is the Stormwater Plan for The Valley as part of the 2004 Plan of Management for The Valley on page 39. There are some 35 specific actions identified, explained and specifically geo-located on the map. The clarity of the image is regrettably poor and almost impossible to read. It has been sourced from the 2004 Plan of Management on Blue Mountains {city} Council’s website concerning the 2021 POM; perhaps the poor clarify of the image was intentional?

Council failed to act on any of the 35 recommended actions of the Stormwater Plan.

Council failed to act on any of the recommended actions of the Bush Regeneration Plan. The only work carried out in The Valley was the ongoing weeding by local residents associated with the Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley bushcare groups. One group focused on the Frank Walford Park area, another along Selby Street Reserve and a third in MacRae’s Paddock.

There was supposed to be stream restoration works, a Heritage Management Plan, native re-vegetation, macrophytle planting around Horace Gates’ artificial lake, removal of the derelict toilet blocks, contruction of a heritage centre and installation of picnic shelters. There was to be a paid re-vegetation coordinator supported by some 20 trainee staff. None of that happened. These are all listed in a Action Plan Table in Section 8.2 of the 2004 Plan of Management from page 71 to 74.

Unbelievably, the total budgeted cost of Blue Mountains {city} Council’s wish list for the entire ‘Masterplan‘ for The Valley came in at a staggering pie-in- the-sky $4,682,000!

The funding for all this was supposed to be gleamed from grants from various departments of the New South Wales Government such as the NSW Department of Conservations and Land Management, the NSW Heritage Office and somehow from from State Treasury, in theory.

That didn’t happen because Council didn’t actually apply for any grant funding for these listed projects.

So what did Council actually manage to do for The Valley over these 17 years (2004-2021) ?

Funding that was secured between the 2004 Plan and the 2021 Plan was from a joint Aboriginal grant between The Gully Traditional Owners (Gundungurra) and the Widjabul traditional custodians the Wilson River region near Lismore in the northern rivers region of New South Wales. A grant of $600,000 was obtained through partnership with Rous Water and Sustainable Futures Australia as part of the Aboriginal ‘Reconnecting to Country‘ project. The funding was used to construct a boardwalk and interpretative Aboriginal signage in the northern (formerly Frank Walford Park) section of The Gully.

A local Aboriginal interpretative pathway design was initiated by the local Aboriginal people in The Gully, not by Council. The entire $600,000 went into funding a cultural focus about the stories of previous residents forciblly evicted for Council’s motor tracing circuit. The funding was not about environmental rehabilitation of The Valley.

Also, a small section of the Catalina Racetrack sleeper fencing was removed near Catalina Lake as a symbolic gesture of finally ending the motor racing usurpation of The Valley since 1957.

Since The Gully was declared an Aboriginal Place on 18th May 2002, motorised use of the track was prohibited by Blue Mountains Council. This ending of the racing era in The Valley came about mainly through the conserted campaigning by local resident activist group the Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley from 1989 to end the racing and the noise. Others wish to claim the credit.

However, occasional mischievous motorised access persisted from time to time for a few years. The steel gate was illegally towed out of its concrete base near the South Katoomba Rural Fire Station in order for someone to gain vehicle access to the old race track. A second steel gate was also illegally removed nearby the Aquatic Centre to gain vehicular access to the track. The odd trail bike and mini bikes were observed by this author illegally racing as recently as December 2005.

During this period , a coppice of willow trees were professionally removed from inside the racetrack, near the disused toilet block. An Aboriginal Liaison Officer, Reg Yates, was employed by Blue Mountains {city} Council for a short time in around 2006. The Council-owned cottage at 23 Gates Avenue was donated to newly formed Gully Traditional Owners, after the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institiute (BMWHI) relocated. The building is occasionally used currently as an office, and meeting place for Gundungurra use. A small art gallery was constructed adjacent. As a local resident, this author usually observes that most of the time the premises are closed and all the window blinds are pulled down.

The Gully Cottage at 23 Gates Avenue in Katoomba. For decades through the 1980s up until 2004 the cottage lay empty after the prevous caretaker had relocated. Council leased the cottage in 2004 to the BMWHI for a penny rent of $1 per year. Then Council gifted it to the Gully Traditional owners and spend tens of thousands renovating it.

At the end of 2011, Blue Mountains {city} Council in partnership with NSW Landcare established a volunteer-based Garguree Swampcare group tasked to rehabilitate the riparian swamp/wetland areas from weed infestations inside The Gully, as well as re-landscaping and planting out locally native vegetation. The name ‘Garguree’ means ‘gully’ in Gundungurra language, apparently according to local historian Jim Smith Ph.D.

We enclose below a complete copy of the final revised Plan of Management of 2004 in Adobe Acrobat .PDF format below. Being a publicly funded community document wholly concerning community land, this document below is freely available to the public for download and printing.

Loading...

Loading...