National Disasters Best for Capable Army

Wednesday, January 5th, 2011by Editor 20110105.

Australia has a history of national disasters, which our detached apathetic politicians repeatedly fail to plan for. Rockhampton Flood of 1918

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~auscqfha/floods.htm

Rockhampton Flood of 1918

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~auscqfha/floods.htm

.

The Central Queensland (CQ) Family History Association Inc. knows and respects the history of Central Queensland. It has well documented the flooding of the Fitzroy River through Rockhampton.

A. E. Herman in his account ‘The Fitzroy River and its early Floods‘ wrote:

‘The Fitzroy River and its tributaries drain a vast expanse of country. Captain Cook, in the Endeavour, sailed along the eastern coast. On May 26, 1770, anchored in and named Keppel Bay, and Flinders, in the Investigator, anchored in the Bay, ascended Sea Hill, named Broadsound and found The Narrows, but failed to discover the great river coming down from the far interior of the continent. The streams that feed the Fitzroy flow through some of the richest grazing and agricultural lands in Queensland. Fresh water continues to some five miles (8 Km) past Yaamba, the old northern crossing 21 miles (33.8 Km) by road and 34 miles (54.7 Km.) by river from Rockhampton. Here tidal influence commences.’ ‘The country drained by the Fitzroy River is estimated to be 55,666 square miles (144,174 square Km.) of which 54,800 square miles (141,932 square Km.) is upstream from Rockhampton and because it drains an immense area it must, of course, carry enormous quantities of water at times.’ [Source: http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~auscqfha/floods.htm ].

Indeed, Rockhampton has flooded many times throughout its history, mainly through the Wet Season.

[Source: Bureau of Meteorology, FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the FITZROY RIVER, http://www.bom.gov.au/hydro/flood/qld/brochures/fitzroy/fitzroy.shtml ]

- Jan 1918: 10.11 metres

- Feb 1954: 9.4 metres

- Jan/Feb 1978: 8.15 metres

- May 1983: 8.25 metres

- Jan 1991: 9.30 metres

- Feb/Mar 2008: 7.50 metres

.

.

And the 2011 flood is expected to peak at 9.4 metres – not as ‘unprecedented‘ as the politicians would have us believe.

.

.

Bligh Expects Queensland Flood Emergency to Exceed $5 Billion

.

Rockhampton Flood @ 9.2m in 2011

Rockhampton Flood @ 9.2m in 2011

.

Rockhampton is again under flood along with many townships of central Queensland.

Today [5th Jan 2011] Queensland Premier Anna Bligh estimated that the total economic impact of the flood damage to Queensland could be $5 billion. Julia Gillard has previously said the Federal Government would be providing assistance that would run into the hundreds of millions to assist the recovery process. Clearly that falls well short of the $5 billion minimum estimated by the Queensland Premier.

And now the politicians are promising, pontificating and filibustering. The political party that herald’s itself as representative of rural Australians, the National Party, has called for a national disaster fund set up and that it be contributed by a household insurance levy. NSW Nationals Senator John Williams said Senator Boswell’s insurance levy should be replaced by a levy on council rates to catch all landowners.

Senator Williams has called for a debate around a national “emergency fund” of up to $10 billion that would help in the event of a flood or other disaster like drought, fire or earthquake.

“Bring on the debate, the money has to come from somewhere. We can’t just pluck it off trees,” he said. “I think a national fund would be a great step forward so the money is there when a fellow Australian is in need of it. There will obviously be some impact on the Australian economy but I would think the Australian economy is large enough and robust enough, as it does almost every year, to be able to cope with these sort of natural disasters,” he said. [1]

.

So serious is this round of disasters in Queensland, Australia’s Prime Minister ‘Julia Gillard ‘has ordered more government funds be diverted to flood-ravaged Queensland in a bid to prevent the state slipping into a long economic slump.’

‘In what may become Australia’s largest and most costly rebuilding operation, clean-up grants of up to $25,000, along with low-interest loans, were offered by the Prime Minister yesterday in addition to the commonwealth’s normal emergency relief payments. Production has almost ground to a halt in the coal industry, while early assessments of Queensland’s agriculture sector have put the cost of the floods at more than $1 billion in lost production.

Authorities also worry that receding floodwaters will reveal unexpected damage to infrastructure, raising the political pressure on all levels of government to chart a clear course to recovery.’ [2]

.

.

National Disaster Management Grossly Neglected in Australia

.

But yet again, after another natural disaster politicians cry to escape all implications of government culpability and so distract public attention by claim of ‘act of God‘ and ‘unprecedented‘ and calling for Australians to chip in and dig deep. Instead of confidently relying upon years of government investment in contingency planning and infrastructure, politicians become shy and distractingly appeal for ‘community spirit’. But now what choice does the community have now that a disaster is upon them? They only have community spirit, despite the bleeding guv’ment.

The floods have also badly affected New South Wales, the Gascoyne and western Victoria. This has included the NSW border town of Goodooga ‘which lies directly in the path of the Queensland floodwaters and is expected to be isolated by the weekend and could remain cut off for the next six weeks.’ The NSW Premier Kristina Keneally has said that evacuations are already underway. The NSW government has declared another eight local government areas to be natural disaster areas, bringing the total to 59. [3]

Also currently occurring is the severe flooding of the Gascoyne Region including the town of Carnarvon, 900km north of Perth. The State Fire and Emergency Services Authority is similarly advising residents to watch for changes in water levels and be ready to evacuate.’ [4] On 19th December 2010, the river had reached 7.7 metres and the president of the Carnarvon Shire, Dudley Masien described the flood the worst he had witnessed. “The hotel roof is only just peaking out of the water“, he said. [AAP 20101220].

Meanwhile in South Australia, over the 2011 New Year period temperatures had been forecast to be 40 degrees Celsius threatening “catastrophic conditions” for bushfire. Luckily an early change averted this risk, but even so several major fires have occurred across South Australia in the past few days including grass fires at Kangarilla, Salisbury East and Keith. The SA Country Fire Service has warned of very high danger ratings remain in place for the North-West Pastoral, North-East Pastoral, West Coast, Eastern Eyre Peninsula, Flinders, Mid-North Yorke Peninsula and the Riverland. [5]

Seriously, Australian governments at all levels need to stop their ‘too-little-too-late’ reactionary responses to emergency management in Australia . The Australian people, the Australian economy and the Australian natural environment deserve better. Currently, we have disparate grossly underfunded State run groups largely staffed by local volunteers – volunteer rural fire services, volunteer state emergency services, and total dependence upon various charities like the Red Cross and Salvation Army.

The responsibility for emergency management throughout Australia has been run on the cheap by successive State and Federal governments since Black Friday of 1939. National Disaster Management is probably the most neglected responsibility of all government services, because to do it right involves long term planning beyond election cycles and costs so much money.

Do we love our ‘sun burnt country‘?

Do we love our ‘sun burnt country‘?

http://poeartica.blogspot.com/2009/02/my-country.html.

Since Victoria’s catastrophic and multiple Black Saturday bushfires about this time two years ago, Australia has emerged from decades of prolonged drought across many states; as well as experienced wild damaging storms; and bushfires this summer in South Australia and WA (again deliberately lit). Australia has copped cyclonic conditions across the north and now flooding rains throughout central and southern Queensland and into northern regions of New South Wales. Each new year that comes the risk of damaging weather is not likely to wane.

Last September, Australia’s closest neighbour, New Zealand, suffered a devastating earthquake in Christchurch, and we don’t have to travel far back to recall the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami that devastated coastal Sumatra, Thailand, Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

Australia has a litany of disasters through its recent history:

- March 1899: more than 400 die in Cyclone Martha at Cape York, far north Queensland.

- December 1916: Flood kills 61 at Clermont, Queensland

- April 1929: Northern Tasmanian floods kill 44

- December 1934: Melbourne floods kill 36 and leave 3000 homeless

- March 1935: Cyclone in Broome, West Australia kills 141

- February 1955: Hunter Valley floods kills 25 in Singleton and Maitland, NSW

- February 1967: Tasmanian bushfires kill 62, most in Hobart

- January 1974: Brisbane floods kill 14 (Cyclone Tracy 25,000 made homeless)

- December 1989: Earthquake in Newcastle, NSW kills 13

- July 1997: Landslide at Thredbo, NSW kills 18

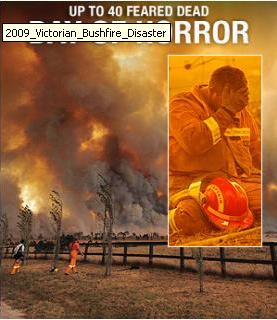

- February 2009: Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria kill 173

- and many others.

.

What is Australia doing about National Disaster Management on its own doorstep and to prepare its poorer neighbours in the South West Pacific? Australia as a rich wealthy nation has a moral responsibility to harbour its close exposed neighbours.

But what disaster monitoring and preparation strategy does Australian have for weather research & monitoring, disaster contingency planning, investment in defensive infrastructure to ensure community resilience, damage mitigation, natural disaster response training?

Where is Australian political leadership in national emergency management?

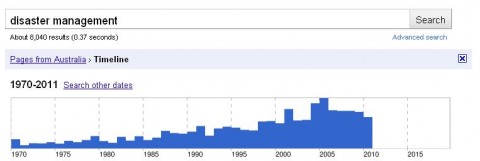

Australia has a recurring pattern of natural disasters. Simple searches on Google reveal that weather history in Australia is only repeating itself. It’s not new. It’s not ‘unprecedented‘ as government politicians try to excuse their leader’s unpreparedness, or is it disinterest?

Classically in Australian literature, Dorothea Mackellar’s Australian epic poem ‘My Country’ prevails and I borrow the following pertinent excerpt, which is prone to regurgitated reference by the media:

“I love a sunburnt country, A land of sweeping plains, Of ragged mountain ranges, Of droughts and flooding rains. I love her far horizons, I love her jewel-sea, Her beauty and her terror — The wide brown land for me!”.

But bear in mind Mackellar wrote that poem back in 1904. She was insightful! Colonial Australia struggling out of raw survival in a retched landscape and through someone’s noble sense of ‘Federation’, Australians will have felt the natural onslaught of the ‘terror’ of natural disasters.

But surely a hundred years hence with the time and luxury of foreign lifestyle, our irresponsible governments do not deserve pardon for their gross public ineptitude.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology has come out declaring it was well aware of the impending torrential downpour from the current La Ni√±a event and of the likelihood of extensive flooding pending for south east Queensland. Historically, La Ni√±a has always caused high flooding cross SE Queensland big river regions. Hello! So where were the Queensland Government’s risk assessment, contingency planning, infrastructure investment and community preparation to lessen the likely disaster scenarios for the big river communities? Is Bligh a joke talking?

We’re now in the 21st Century, not Mackellar’s era. Australians in all states and territories have a public right to expect that our Australian national government will dutifully properly prepare, manage and mitigate the impacts of national disasters. It is all about good governance. What do we pay taxes for if it is not for times like this?

While many of us who can take out general insurance, those insurance companies can only respond to natural disasters in a financial sense but after the disaster. But it is not the job of insurance companies to manage disaster; it is without equivocation the responsibility of government and quite simply that is why we must pay our taxes throughout our lives. Government civic infrastructure is still not in place to mitigate known historic recurring disaster risk and so since the risk remains so the proportional premium increases. Consequently, many thousands of Australians are in a Catch 22. They are not eligible or cannot afford the requisite insurance to cover their property against natural disaster because the premiums are prohibitively expensive, but they can’t sell and relocate because their property values will have plummeted.

Over the decades thousands of Australians have had their building approved by government on land with a history of natural disaster – flooding, bushfire and drought for instance. If that is not reckless enough, governments at all levels continue to renege on disaster risk mitigation and defensive infrastructure to withstand known disaster types. So in the event of these recurring natural disasters, look at the record of the Australian Government’s contingency planning and performance protecting the Australian public – their lives, property, and to Australia’s most vulnerable our wildlife and its natural habitat? Thousands of hectares of forests have been cleared across the Brisbane River that naturally would have absorbed much of the deluge. Now bare hills and hard surfaces and many thousands of storm water drains, the rains are not absorbed. Housing development continues to be approved in bush settings that are undefendable in the event of a bushfire. Agricultural approval is provided for cropping on marginal lands with repeated histories of drought and/or flood.

Unlike back in 1904, Australia in 2011 is supposedly a wealthy, technologically advanced society. Australia easily has the financial and resource capability to be disaster prepared at national level. But failure to contingency plan condemns Australians to ‘planning to fail‘. When disaster hits Australians are on their own! When a government lets down its people it has lost all legitimacy.

.

So what is ‘Emergency Management Australia’ ?

.

Nationally, Australia has no central organisation that deals with national disasters, natural or otherwise. The job is left to the relevant State Government concerned; somewhat a leftover remnant of colonialism.

There is a token agency under the Federal Attorney General’s Department, called Emergency Management Australia [compulsorily abbreviated to an acronym like most government agencies to ‘EMA‘, but the name is more impressive than the tasks it performs.

In 2005 under the Howard Government, Emergency Management Australia was on paper “tasked with co-ordinating governmental responses to emergency incidents” and with providing training [at Mount Macedon] and policy development, yet “the actual provision of most emergency response in Australia (was)… delivered by State Governments.”

[Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Emergency_Management_Australia&oldid=32590701]

.

In November 2007 under the Rudd Government, the Emergency Management Australia focus was modified, slightly:

“On request, the Australian Government will provide and coordinate physical assistance to the States in the event of a major natural, technological or civil defence emergency. Such physical assistance will be provided when State and Territory resources are inappropriate, exhausted or unavailable.” – and they gave it an acronym ‘COMDISPLAN‘ standing for Commonwealth Government Disaster Response Plan.

[Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Emergency_Management_Australia&oldid=174306765 ]

.

That is, in lay terms, the Australian Government will only help in national emergencies when the States can’t handle a public emergency.

Such a bureaucratic attitude is hardly proactive leadership from our wealthy developed nation!

.

In recent years, the Rudd/Gillard Government renamed the organisation Emergency Management in Australia (visit the site http://www.ema.gov.au/), which seems to have been a way of playing down its national leadership role to one of being simply an informational resource. Again, this is divulging responsibility for national emergencies to the next tier of government. Imagine if the states and territories did the same and divulged such responsibility down to local councils?

Emergency Management in Australia doesn’t even have a dedicated minister responsible. Instead, the entire responsibility is tagged on to the Federal Attorney General’s Department. Currently the task is being delegated to an ‘Acting’ Attorney-General Brendan O‚ÄôConnor and shared with Minister for Human Services Tanya Plibersek. It is as if the Australian Government has a head in the sand approach to national emergencies at home, hoping they won’t happen, but when they do, she’ll be right mate! – we’ll fob our way through it as best we can with what’s lying around.

What a bloody irresponsible approach to national emergency management! And all the government does is to encourage the thousands of Queensland residents affected by the flooding to lodge a claim for the Australian Government‚Äôs Disaster Recovery Payment ‘AGDRP‘ – another acronym!

Other reactionary responses from Canberra are currently listed on the EMA website as ‘Flood-affected residents urged to apply for assistance’, ‘Extra disaster assistance for flood-affected communities in Queensland’, a ‘Boost for Territory Disaster Resilience’, a ‘Boost for Tasmanian disaster resilience’, ‘Commonwealth response to the final report of the Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission’, and when in doubt, ring Triple Zero (000). How reassuring!

Perhaps one initiative positively worth noting is that the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) met in Brisbane on 7 December 2009 and agreed to a range of measures to improve Australia‚Äôs natural disaster arrangements. COAG recognised “the expected increase to the regularity and severity of natural disasters“, and so agreed to a new whole-of-nation ‚Äòresilience‚Äô based approach to natural disaster policy and programs.” Under a Natural Disaster Resilience Program, at Federal level we are now supposed to have Commonwealth funding for disaster mitigation works and support for emergency management will be approximately $110 million over four years.

Well at least it’s a step in the right direction – adopting a ‘whole-of-nation’ approach is long overdue. Yet the current funding scope again is classically ‘too-little-too-late‘. The politicians pontificate. How much of this $110 million will be required for the 2010 Queensland Floods disaster? How much reached the victims of the 2009 Black Saturday disaster across Victoria?

What inevitably happens is that when the disaster situation gets beyond the local volunteers and State and Federal Governments are in a lather not being able to cope, the standard response is to call in the Army? As if the Army knows better than the experienced volunteers?

But for a national government to resort to calling in the Army is a public confession that the government’s emergency management plan has utterly failed the people. At this very point government raises the white flag of failure in national emergency management. One’s government is suddenly incompetent.

And just like what the Federal Government did in Victoria after Black Saturday’s shemozzle of a disaster management, this is just what they are again doing now in Queensland. Enter Major General Mick Slater, poor bugger!

.

.

Army deployed to manage the 2011 Queensland Floods Recovery

.

On 5th January 2011, Queensland Premier Anna Bligh announced that Major General Mick Slater would lead the state’s flood recovery taskforce, as more than

200,000 Australians in 40 communities across Queensland have been impacted in some way by the floods. The Army will be tasked to rebuild houses, economies, regional communities and infrastructure. It is estimated that about 1,200 homes across Queensland have been inundated by floodwaters thus far, with another 10,700 homes affected and 4,000 residents evacuated, and the flood bill could be well above $5 billion.

But as a freshman to national disaster management, incoming Army officer Slater has revealed that despite his Army experience has not prepared him for this challenge:

…’one of his first duties will be to talk to Major General Peter Cosgrove, who headed the Innisfail rebuilding project after Cyclone Larry in 2006. “I believe he’s returning from overseas today and I hope to speak to him tonight. This is early days for me. I’ve just been appointed to this job, but I do understand that time is of the essence as we progress down the recovery mode. However, it is very important that we get it right the first time. “If we rush in and do patch-up jobs… then we will have got it wrong. We must get it right from the start and that will take some time.” .[Source: ‚ÄòArmy general to head flood recovery taskforce‚Äô, ABC, 5th January 2011, http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2011/01/05/3106898.htm ]

.

Reading between the lines, it is clear that the Army is not trained, skilled, experienced or prepared to deal with national disasters. The Army is traditionally trained to fight battles against a human enemy. It has recently evolved to deal with peacekeeping missions, but national disasters remain outside its core skill set.

Premier Bligh has recognised:

“This is a large and complex effort. It will not happen quickly. It will require all of us working together across different levels of government.”

And so once again, instead if a single national professional response, a hotch-potch of agencies is thrown together from Federal and State Governments. Volunteers and charities will play a key role and asking the public for charity has already started.

Once again a desperate government declares ineptness and phones a friend in Canberra – ‘please send in the Army and make our politicians look like we’re taking decisive action what now there’s a good chap, meet you at the club for afters’.

.

.

Australian Army Not Equipped for National Disasters

.

CRITICAL QUESTIONS: What does the Australian Army know about national disaster management? More that the State Emergency Services or Fire Brigades? I don’t think so. But the Army has resources, and that it why it is brought in. So why don’t the emergency agencies have the resources in the first place? Emergency agencies do emergencies. The Army fights wars.

Let’s look at the record…

Army Deployed to Manage the Recovery after the 2009 Victorian Bushfire Disaster

Between 10th February and 14th March 2009, Australian Prime Minister Rudd and Victoria‚Äôs Premier Brumby agreed to have the Australian Army Reserve deployed to assist the multiple emergency services in the immediate aftermath ‘mopping up’ of the Victorian bushfire emergency, dubbed by the media as ‘Black Saturday‘. The Army set up Joint Task Force 662 based to the north of Melbourne under the command of Brigadier Mike Arnold.

Under ‘Operation VIC FIRE ASSIST’, Joint Task Force 662 involved about 450 Army Reservists in a recovery support role – mainly a construction and an engineering regiment with assistance from the School of Armour and a Combat Services Support Battalion. Specifically, ‘Search Task Group’ was set up comprising around 160 Army Reserve soldiers to assist police locate human remains with perimeter security around many townships and residents destroyed including the two Kinglakes, Strathewen, Marysville, and Flowerdale. An RAAF AP-3C Orion aircraft was deployed to provide aerial imagery to assist in the identification of residences affected by the fires.

Army support included delivering food parcels, and putting tents and facilities into place to help accommodate, feed and support people left homeless.

An Engineer Support Group, comprising around 70 personnel, five army bulldozers, a front-end loader and a grader, working with the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment and Country Fire Authority, to assist with improving fire breaks and containment lines, and clearing roads of vegetation and debris throughout the many bushfire affected areas.

Somewhat outside core duties, Defence personnel from Northern Command and Townsville launch bushfire undertook direct fundraising collecting donations at the gates to Larrakeyah Barracks, Northern Territory and Lavarack Barracks, Townsville. On Friday 13th February five RAAF members from Combat Support Unit Edinburgh also conducted a collection in aid of the Red Cross Bushfire Appeal at the main and south gates of RAAF Base Edinburgh.

[Source: http://www.defence.gov.au/media/download/2009/feb/20090210/index.htm ].

So the Army involvement in dealing with the national disaster of ‘Black Saturday‘, was effectively a post-disaster mop up operation assisting police and providing civil engineering support and relief effort. The Army was not deployed at the outset of the known bushfire risk on Monday 3rd January 2009 when weather forecast was extreme and fires had already started. Nor was the Army deployed during the disaster period itself – Saturday 9th through Monday 11th January. This is due to the Army not being best trained to deal with such emergencies and the false expectation that the volunteer Country Fire Authority were.

The emergency conditions were such:

.

.

Army Deployed to Manage the Response and Recovery after Cyclone Larry in 2006

Severe Tropical Cyclone Larry made landfall in Far North Queensland as a Category 4 storm crossing the coast near Innisfail at dawn on 20 March 2006. With wind gusts up to 240kph Cyclone Larry was regarded as the most powerful cyclone to affect Queensland in almost a century. In addition to the high winds, the cyclone moved inland and developed into a tropical depression causing protracted torrential rains and extensive over the following week.

The wind and flooding damage extended north to Cairns and the Atherton Tablelands and as far west as Mount Isa. After landfall, Tropical Cyclone Larry moved over north-western Queensland on 22‚Äì23 March, with heavy rain falls across the region. Most of the damage occurred in the Innisfail coastal region where 80% of buildings were damaged, power and phone lines were downed, water was contaminated and the region’s main agricultural crop, bananas, was decimated. The economic damage bill came to around A$1 billion in damage, and there was one fatality.

The usual array of disparate organisations attended the immediate emergency response including the standard local emergency services (fire brigades, ambulance and police) as well as local volunteer fire brigades (Thuringowa) and unpaid State Emergency Service volunteers. Perhaps unlike other states, the umbrella organization Emergency Management Queensland initially led and coordinated the disaster management (response and recovery) including SES, Emergency Service Units, and EMQ Helicopter Rescue.

Local councils were handed authority to enforce mandatory evacuations once Queensland Premier Peter Beattie declared Larry a ‘disaster situation’. Desperately though, even local prisoners who ‘could be trusted’ were considered for recovery and clean up work-gangs, then around 150 tradesmen from around Australia arrived in Innisfail within days to repair houses, schools and public buildings.

The Australian Army was also deployed early. Within hours of the cyclonic winds subsiding, the nearby Townsville-based 3rd Brigade and Cairns-based 51st Battalion were deployed as well as the Far North Queensland Regiment. Three UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters were reserved for rescue and logistical support. A Combat Services Support Battalion was set up to manage the disaster relief effort based at Innisfail Showgrounds to provide basic food, water, shelter and sanitary needs to evacuated residents. Onsite health care, environmental advice, fresh food and purified water (as well as testing local supplies), tarpaulins, bath and shower facilities, and up to 500 beds were provided.

The Navy and Air Force were also deployed including a CH-47 Chinook heavy lift helicopter, one Seahawk helicopter, three Navy Balikpapan class LCH Landing Craft, two Caribou aircraft, two C-130 Hercules, and several LARC-V amphibious 4WD vehicles.

By 23rd March, three days after the cyclone hit, Prime Minister John Howard and Premier Beatty appointed former Chief of the Australian Defence Force, General Peter Cosgrove, to take charge of recovery efforts labelled the ‘Cyclone Larry Taskforce‘. One quick decision made by Cosgrove was to call for an economic assessment by state and federal governments, and specified a moratorium on businesses’ debt repayments to banks for 3 months. (An outside the Army square type of thinking).

[Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyclone_Larry]Previously as a Major General in the Army, Cosgrove had successfully managed the 1999-2000 complex UN INTERFET peacekeeping taskforce in East Timor dealing with post-war humanitarian and security crisis. He was credited with commanding thousands of personnel from many countries and completing a successful mission to transition the country to relative stability.

[Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/INTERFET].

This experience had given Cosgrove disaster management skills beyond traditional Army combat roles, and clearly had well prepared him to lead the Cyclone Larry Taskforce. But Cosgrove’s peacekeeping civil emergency experience in a complex environment singled him out as the best person to lead the management of a national disaster in Australia. His success ought to serve as a model for future emergency management planning.

Yet Cosgrove’s experience is atypical of the Australian Army’s broader experiences. The Army’s role and experience in national disasters has been purely responsive and supportive. The main contributions by the Army in national disasters has been using Army equipment and military training to try to help a civil emergency. Following desperate orders from the Prime Minister of the day, the Army responds the best it can with what it has got in a situation it is not expertly trained or resourced to do professionally. The Army’s role in emergency management is not strategic, national nor involved in risk assessment, contingency planning nor leadership of the emergency response. But it should be.

The Australian Regular Army and its volunteer Army Reservists are tasked for traditional military combat, not for the new emerging role of international peacekeeping, nor for managing civil unrest, nor for anti-terrorism, nor for natural and national disaster management. Yet recent world events and trends point to such roles becoming more important and likely than traditional military combat. So the role of the Army, its capabilities and its culture need to change to better meet Australia’s true ‘defence’ needs in the broader 21sst Century context. The Army’s 20th Century traditional military combat role belongs to the 20th Century.

.

.

Irresponsible to Expect State-based Volunteers to Manage National Disasters

.

Tropical cyclones are not new in northern Queensland nor indeed across northern Australia. They invariably occur every Wet Season generally between the months of November and April and each year only varies in their intensity. This author experienced Cyclone Joy back in 1990 while living in Cairns. The need for a national disaster management organisation probably dates back to Cyclone Tracy of Christmas 1974 which flattened Darwin.

. Darwin following Cyclone Tracy at Christmas 1974

© Film Australia. http://www.abc.net.au/aplacetothink/html/cyclone.htm

Darwin following Cyclone Tracy at Christmas 1974

© Film Australia. http://www.abc.net.au/aplacetothink/html/cyclone.htm

.

Australian natural history is one of recurring natural disasters. Current flooding along the Murrumbidgee River in New South Wales is again affecting the town of Gundagai, but since Australian history is poorly taught these days, few will be aware that a major flood back in 1852 wiped out the original town site of 71 buildings, and 89 of the town’s 250 inhabitants perished.

Bushfires, severe storms and cyclones, prolonged droughts, flooding rains, and even earthquakes have frequented the landscape, almost annually. With climate change apparent, however caused, there is every expectation from climate science that extremes of weather in Australia, around the world and in our region, will not lessen but more probably will increase both in frequency and severity. New forms of natural disaster may also occur in future such as tsunamis, landslide (recall Thredbo 1997), storm surge, even possible tornado or tsunami, a volcanic eruption from our north or plague and pestilence. National disasters affecting Australia and our region may also not only be naturally caused, such as a major bridge collapse, major dam collapse, major gas explosion and given ongoing tensions and terrorist events pervading our now global society, new forms of national disaster may loom.

While the 1939 ‘Black Friday’ bushfires in Victoria killed 71 people, the accompanying heat wave – which triggered the blazes – claimed 438 lives and yet remains largely unacknowledged. With climate change, a recurrence is almost certain.

Is Australia prepared to cope, manage and mitigate the effects of national disasters? Is the current emergency management framework centred on State-based and local volunteers adequate to the task?

In localised low grade emergencies, the current system generally copes well. But when it comes to national disasters like Cyclone Larry, Black Saturday and the 2011 Queensland Floods, the answer is clearly ‘no’. The test is, do most Australians believe that the emergency authorities in each case were sufficiently prepared and resourced and adequately responded? Do most Australians believe that the impacts of these national disasters could have been considerably mitigated by better risk assessment, contingency planning, the immediacy and appropriateness of the response and co-ordination of recovery?

Such questions go the core of Australia’s national security and to the role and expectation of government to protect its people and assets. The concept of ‘national security‘ needs to extend beyond the narrow military sense to encompassing defence against all forms of adverse impact to our society, economy and environment. National security also extends to Australia’s immediate region; since to ignore national disasters of our neighbouring nations would be not only immoral but likely have spillover effects on Australian eventually.

So what to do about the problem of recurring national disasters?

Government urban planning, human settlement approvals and investment in civic infrastructure to properly protect its citizens from the impacts of national disasters, and the funding of general and life insurance are interrelated key socio-economic issues that will likely come to the fore as communities recognise history repeating itself and governments are found wanting – but they are a focus is for another article.

The contention in this article is not to criticise the work of emergency service volunteers and professionals of the many organisations that get involved, but rather to highlight that the framework and resources in which they operate is woefully inadequate. Volunteers must feel like pawns in a loosely run reactive system, but culturally they are condemned if they dare criticise.

Yet the repeated evidence is that Australia’s current emergency management framework fails the delivery and performance expectations of Australians in our wealthy and advanced society. Look at the records since the first national disaster of the 1939 Black Friday bushfires! Below in the Further Reading section, a number of online references provide links to the many national disasters throughout Australian history. Natural history is repeating itself, but regrettable so is the laissez faire, even ‘head-in-the sand’ attitude of successive Australian governments to avoid serious investment and planning in emergency management for national disasters.

National disasters are costing Australian lives, communities, economies and environments. The full triple-bottom-line costs (direct and indirect) cumulatively reach the billions almost annually. The cost has to be paid in one way or another and often it is in the form of economic loss, decline in rural society and environmental degradation. Instead of governments investing billions up front to mitigate the damage and costs, governments are forking out afterwards anyway and Australian morality is tweaked to donate in order to make up the funding shortfall. The old adage of ‘prevention being better than the cure‘ holds so true here, but the solution seems beyond the short term narrow thinking of our political leaders.

.

‘So serious is this round of disasters in Queensland the Prime Minister ‘Julia Gillard has ordered more government funds be diverted to flood-ravaged Queensland in a bid to prevent the state slipping into a long economic slump.’.

In what may become Australia’s largest and most costly rebuilding operation, clean-up grants of up to $25,000, along with low-interest loans, were offered by the Prime Minister yesterday in addition to the commonwealth’s normal emergency relief payments. Production has almost ground to a halt in the coal industry, while early assessments of Queensland’s agriculture sector have put the cost of the floods at more than $1 billion in lost production.’ .

[Source: ‘PM Julia Gillard to help flood-hit Queensland weather storm‘, by Sean Parnell and Jared Owens, The Australian, 4th January 2011. http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/pm-julia-gillard-to-help-flood-hit-queensland-weather-storm/comments-fn59niix-1225981305357 ]

.

“Surely it’s time for Julia Gillard to stop seeing the Queensland floods as a series of media opportunities and start showing some practical leadership. She does not appear to have had the truly national implications of this disaster made clear to her.”

[Source: David Williams, Frewville, SA, Letter to the Editor, The Australian, 20110112, p13) ..

Full Costs of National Disasters Many Times Greater than Government Investment in its Volunteer Emergency Management Model

.

http://on-walkabout.com/tag/bushfires/

.

http://on-walkabout.com/tag/bushfires/

.Economic Cost of National Disasters of Living Memory

In terms of direct economic damage alone, in Australian dollars the Queensland Bligh Government has estimated the cost of the current 2011 Queensland Floods to exceed $5 Billion. The economic damages bill for the 2009 Victorian Bushfires exceeded $2 billion. The economic cost of the 2006 Cyclone Larry was in excess of $1.5 billion. The 2003 Canberra Bushfires insurance cost came to $250 million. The 1991-95 drought across in north-eastern New South Wales and much of Queensland cost the economy around $5 billion.

In 1990, over one million square kilometres of Queensland and New South Wales (and a smaller area of Victoria) were flooded in April 1990. The towns of Nyngan and Charleville were the worst affected with around 2,000 homes inundated. Six people were killed and around 60 were injured.

The insurance claims payouts from the 1983 Ash Wednesday Bushfires for Victoria and South Australia combined were $1.3 billion (2007 adjusted terms). The preceding four-year drought across south-eastern Australia (1979-1983) cost the economy around $7 billion mainly in agricultural losses.

In January 1974, the weakening Cyclone Wanda brought heavy rainfall to Brisbane and many parts of south-eastern Queensland and northern New South Wales. One third of Brisbane’s city centre and 17 suburbs were severely flooded. Fourteen people died and over 300 were injured. Fifty-six homes were washed away and 1,600 were submerged. At Christmas 1974 Cyclone Tracy killed 65 people and caused over 600 injuries in Darwin and 70% of all houses had serious structural failure. The total damage bill was around $800 million (1974 $s). In 1970 Tropical Cyclone Ada caused severe damage to resorts on the Whitsunday Islands, Queensland. Fourteen people were killed and the damage bill was estimated at $390 million.

Many other national disasters have occurred in Australia as well as in neighbouring countries. The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami claimed more than 150,000 people dead or missing and millions more were homeless in 11 countries, making it perhaps the most destructive tsunami in history. An estimate by the World Bank and Indonesian government put the total bill for the destruction of property and businesses at more than US$4.4 billion.

[Sources: Various references online, most notably http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/naturaldisasters/ ].

Many minor emergencies that occur each year particularly involving storms and bushfires would add to the aggregate costs of these major events.

So a broad brush stroke estimate of the direct economic costs alone of national disasters affecting Australia would average in the range of between $2 billion and $5 billion per year. This excludes the social costs of people experiencing trauma and losing loved ones and livelihoods as well as the unknown environmental costs which should be measured and included and disclosed by the Australian Government so that the cost truth of national disasters is know to the Australian public. Without triple bottom line measurement, the true scale of the problem remains hidden and the ability to problem solve and to make cost effective and cost benefit investment decisions is greatly diminished.

.

Disaster Compensation

So in the current instance involving the 2011 Queensland Floods, Prime Minister Gillard has promised a $25,000 grant to each flood-affected property owner and $15,000 to those similarly affected in the flooded Gascoyne Region of Western Australia. Assumedly, flood-affected property owners in northern New South Wales will be similarly compensated. Under Queensland’s Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA) the State and Federal Governments share the compensation costs and include other Disaster Relief Measures such as providing Counter Disaster Operations and a Personal Hardship Assistance Scheme (to alleviate personal hardship), an Associations Relief Assistance Scheme, Restoration of Public Assets, Concessional Loans to Primary Producers, Freight Subsidies to Primary Producers, and Concessional Loans to Small Businesses.

[Source: Queensland Disaster http://www.disaster.qld.gov.au/support/ ].

But the financial compensation offered by the Australian government varies with each national disaster and the aggregate cost information is not readily available online, perhaps intentionally. In the main, each state government sets up a range of compensation funds on a disaster event basis. The Australian Government provides a website Disaster Assist that summarises what compensation is available for a given disaster event, usually with references to CentreLink and back to the relevant state government. Visit: http://www.disasterassist.gov.au/www/disasterassist/disasterassist.nsf/

In the case of the 2011 Queensland Floods disaster, an Australian Government Disaster Recovery Payment rate is $1,000 per eligible adult and $400 per child.

“Claims for this assistance can be lodged at Centrelink until 4 July 2011 as application for the payment is available for a period of up to six months.”

Identified Disasters on the website are listed as follows:

Current Disaster Assistance * Queensland Floods – December 2010 * Financial assistance for flooding and severe weather events November – December 2010 * NSW Flooding – October 2010 * South East Queensland Flooding – October 2010 * New South Wales Weather Event – September 2010 * Victorian Flooding – September 2010 * Victorian Bushfires – January/February 2009 . Previous Disasters * Victorian Storms – March 2010 * Queensland Floods – March 2010 * WA bushfires December 2009 * Mid-North Coast Flooding – November 2009 * Samoa Tsunami – September 2009 * Human Swine Influenza (H1N1) Outbreak 2009 * New South Wales Floods – March 2009

.

Annual Funding in Australian Emergency Management

On 12th May 2009, the Rudd Federal Government issued a media release entitled ‘Improving Disaster Resilience‘ as part of the Federal Budget 2009-2010. It stated:

‘The Rudd Government will invest $79.3 million to strengthen efforts to prepare for and combat major natural disasters. A comprehensive ‚ÄòDisaster Resilience Australia Package‚Äô will integrate a number of existing emergency management grant programs, providing the flexibility to effectively meet the requirements of local communities threatened by disaster. The additional funding will be part of this new package. …The package will integrate the current Bushfire Mitigation Program (BMP), Natural Disaster Mitigation Program (NDMP), and the National Emergency Volunteer Support Fund (NEVSF). The funding will:…In addition, the Commonwealth will also provide more than $12.8 million over the next four years to assist States and Territories lease additional fire fighting aircraft for longer periods during bushfire seasons. Aircraft will be leased through the cooperative National Aerial Firefighting Arrangements (NAFA) and will help individual States and Territories access a range of specialised aircraft that would otherwise be out of reach. ‚ÄúAerial firefighting has emerged as a valuable tool in the fight against bushfires and the national arrangements have proven to be an efficient, collaborative approach that shares the cost of these specialised assets,‚Äù Mr McClelland said. This additional funding brings the Government‚Äôs total contribution to the National Aerial Firefighting Arrangements to $14 million per year from 2009-2010. Following recommendations of the 2008 Homeland and Border Security Review, the Government will also establish new briefing facilities and establish an enhanced Government Coordination Centre to support decision-making in the event of a national crisis or major natural disaster.’ [Source: Australian Government – Attorney General’s Department]

- support disaster mitigation works including flood levees and fire breaks

- assist Local Government meet its emergency management responsibilities

- support the work of volunteers in emergency management

- build partnerships with business and community groups to improve their ability to respond to emergencies.

.

On 8th June 2010, the New South Wales Keneally Government announced it would invest $972 million in emergency services across NSW, including the NSW Fire Brigade, NSW Rural Fire Service and NSW State Emergency Services.

The NSW Emergency Services Minister, Mr Whan states:

“Our emergency services are our first line of defence against storms, floods, tsunami, fires and other emergencies and it is vital that they have the personnel, facilities and resources they need to protect communities around NSW.”“…Over the past two years, our SES volunteers have responded to a string of emergencies, including major floods in Northern NSW, the Central West and Far West.

“Given the predicted impacts of climate change, this workload is expected to increase in coming years and it is important that the SES is ready to face the challenges ahead.”

The Budget highlights for the emergency services were listed as follows:

NSW Fire Brigades (professionally paid)The NSW Fire Brigades 2010/11 budget is $637 million. Spending includes: * $18 million for more than 35 new fire engines and specialised vehicles * $8.4 million for firefighting and counter terrorism plant and equipment * $10 million for Cabramatta and renovated fire stations and training facilities * $2.5 million for Community Fire Units * $1.3 million for a Workplace Conduct and Investigation Unit .

NSW Rural Fire Service (largely unpaid volunteers)

The Rural Fire Fighting Fund for 2010/11 is $220.4 million. Spending includes: * $32.2 million for about 200 bush fire tankers * $16 million for new and renovated stations and fire control centres, including installing water tanks * More than $17 million for bush fire mitigation, including $6.7 million for works crews * $7.8 million for aerial firefighting resources .

NSW State Emergency Service (largely unpaid volunteers) The State Emergency Service budget for 2010/11 is $64.1 million. Spending includes: * $2 million to assist with the cost of about 60 emergency response vehicles * $1.4 million for rescue equipment, including $600,000 for about 20 floodboats * $1.4 million for communication and paging systems * $930,000 towards the cost of upgrading unit headquarters around NSW [Source: http://www.nswfb.nsw.gov.au/news.php?news=1656 ]

.

The division of emergency services management by the State of NSW into three separate governments agencies, of which only the urban-based fire brigade is fully professionally paid, is typical of the other Australian states and territories. NSW is the most populous state in Australia and so has the greatest taxation revenue with which to fund its public services such as emergency services. An actual annual aggregate figure of the combined capital and recurrent expenditure on emergencies services across Australia would be welcomed and should be disclosed on the Australian Government’s website.

But for a quick comparison, let’s assume that the annual aggregate investment by governments at all levels across Australia, including that of local councils is in the range of $3 billion to $4 billion per year. The investment is almost on par with the economic cost outlay of Australia’s national disasters. It is important to recognise that the funding cost is separate from the disaster economic cost, and that the socio-environmental costs are excluded.

So Australia’s total economic spend on national disasters and civic emergencies probably averages close to A$10 billion per year.

.

.

A Case for Disaster Management to be ‘professionally nationalised’ across Australia.

Google Search on ‘Disaster Management‘ (globally)

Google Search on ‘Disaster Management‘ (globally).

First some problem solving questions:

- Why are national disasters causing such massive impact on Australia’s environment, society and economy?

- Is the damage caused by natural disasters impossible to mitigate (a fatalistic acceptance), or can more be done to mitigate their damage to the environment, society and economy?

- Does Australia have a history of natural disasters and are any of the recent ones socalled ‘unprecedented‘ or are they just a repeat of what has gone before and even less severe than previously?

- Who is responsible for planning and mitigating the impact of national disasters when they do occur?

- Is not national disaster management as vital a function as military defence?

- Is the current framework of multiple disjointed independent State and locally based organisations the most effective and efficient structure to do the job?

- What if Australia’s Defence Force had the same framework and organisational structure as current emergency management? Could Australia’s Defence Force perform the same as it currently does? Why not?

- How is current disaster contingency planning and response performance measured and are the measures appropriate to quantifying the desired standards of performance?

- Is the current disaster contingency planning and response performance acceptable to the Australian community?

- How short of ideal is the current performance?

- Why is the current emergency management response not able to mitigate the impact to an acceptable level?

- How do Australia’s emergency management operations measure up against world best practice?

- What countries have world best practice emergency management?

- Does the funding structure facilitate or inhibit the capacity of the emergency planning and response?

- Are grants and subsidies an appropriate revenue source for such a vital service?

- Ought funding be guaranteed as it is with the Defence Forces?

- What are the alternatives to Australia’s current disaster contingency planning and response framework?

- Do other countries have a proven success record of disaster contingency planning and response, which Australia could learn from and adapt?

.

.

United States: Federal Emergency Management Agency

.

Probably the global best practice structure currently for dealing with national disaster management (from risk assessment through reconstruction phasing) exists not surprisingly with the United States of America. Try searching elsewhere and frankly, the US is hard to beat.

The United States National Response Framework (NRF) is part of the National Strategy for Homeland Security that presents the guiding principles enabling all levels of domestic response partners to prepare for and provide a unified national response to disasters and emergencies.

Until 1979,the United States had no comprehensive plan for federal emergency response. Then President Jimmy Carter signed an executive order creating the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which consolidated the emergency response duties from multiple agencies across the country that each had disjointed emergency operational plans. National legislation was enacted in 1988 to effectively nationalise Federal response to disasters. Under the National Contingency Plan, multiple organisations were united to deal with disaster preparedness and response.

In 1992, US President Bill Clinton appointed James Lee Witt as the head of FEMA, who substantially changed FEMA to adopt an all-hazards approach to emergency planning. Clinton elevated Witt to a cabinet-level position, giving the Director access to the President. So for the first time, a national disaster management organisation had a National Response Plan and reported directly to the head of the US government – the President.

Since then, following the 2001 September 11 terrorist attacks, the United States thrust disaster management to the forefront of national priority for obvious reasons and it is due to this that the United States probably more than any other country, bar perhaps Israel, has a world leading disaster management structure today. Since 2003, the Department of Homeland Security has absorbed FEMA and since 2008, the National Response Plan has been replaced by the National Response Framework.

Check out: US Federal Emergency Management Agency and FEMA National Response Framework [NRF]

The United States National Response Framework (NRF) is part of the National Strategy for Homeland Security that presents the guiding principles enabling all levels of domestic response partners to prepare for and provide a unified national response to disasters and emergencies. Building on the existing National Incident Management System (NIMS) as well as Incident Command System (ICS) standardization, the NRF’s coordinating structures are always in effect for implementation at any level and at any time for local, state, and national emergency or disaster response.

.

.

NRF five key principles

.

- Engaged partnership means that leaders at all levels collaborate to develop shared response goals and align capabilities. This collaboration is designed to prevent any level from being overwhelmed in times of crisis.

- Tiered response refers to the efficient management of incidents, so that such incidents are handled at the lowest possible jurisdictional level and supported by additional capabilities only when needed.

- Scalable, flexible, and adaptable operational capabilities are implemented as incidents change in size, scope, and complexity, so that the response to an incident or complex of incidents adapts to meet the requirements under ICS/NIMS management by objectives. The ICS/NIMS resources of various formally-defined resource types are requested, assigned and deployed as needed, then demobilized when available and incident deployment is not longer necessary.

- Unity of effort through unified command refers to the ICS/NIMS respect for each participating organization’s chain of command with an emphasis on seamless coordination across jurisdictions in support of common objectives. This seamless coordination is guided by the “Plain English” communication protocol between ICS/NIMS command structures and assigned resources to coordinate response operations among multiple jurisdictions that may be joined at an incident complex.

- Readiness to Act: “It is our collective duty to provide the best response possible. From individuals, households, and communities to local, tribal, State, and Federal governments, national response depends on our readiness to act.”

.

.

‘NRF CORE’

.

- Roles and responsibilities at the individual, organizational and other private sector as well as local, state, and federal government levels

- Response actions

- Staffing and organization

- Planning and the National Preparedness Architecture

- NRF implementation, Resource Center, and other supporting documents incorporated by reference

.

.

NRF ANNEXES

.

* ESF #1 – Transportation

* ESF #2 – Communications

* ESF #3 – Public Works and Engineering

* ESF #4 – Firefighting

* ESF #5 -Emergency Management

* ESF #6 – Mass Care, Emergency Assistance, Housing, and Human Services

* ESF #7 – Logistics Management and Resource Support

* ESF #8 – Public Health and Medical Services

* ESF #9 – Search and Rescue

* ESF #10 – Oil and Hazardous Materials Response

* ESF #11 – Agriculture and Natural Resources

* ESF #12 – Energy

* ESF #13 – Public Safety and Security

* ESF #14 – Long-Term Community Recovery

* ESF #15 – External Affairs

.

.

NRF SUPPORT ANNEXES:

.

* Critical Infrastructure and Key Resources (CIKR)

* Financial Management

* International Coordination

* Private-Sector Coordination

* Public Affairs

* Tribal Relations

* Volunteer and Donations Management

* Worker Safety and Health

.

.

NRF INCIDENT ANNEXES:

.

* Incident Annex Introduction

* Biological Incident

* Catastrophic Incident

* Cyber Incident

* Food and Agriculture Incident

* Mass Evacuation Incident

* Nuclear/Radiological Incident

* Terrorism Incident Law Enforcement and Investigation

.

.

.

Proposed New Defence Corps: Australia’s ‘Civil Emergency Corps‘

.

As one solution to Australia’s failing governance of national disasters, I propose the complete overhaul of Australia’s current state-based and volunteer based disparate organisations, by consolidating, nationalising and professionalising them all into one. I propose a new national defence corps be established under new national legislation – Australia’s ‘Civil Emergency Corps‘. This Corp would be an equal partner with our Army, Navy and Air Force, but instead of focusing on national defence against human-based threats, the Civil Emergency Corps will focus on national defence against mainly natural threats.

.

A special national commission should be established by the Australian Government to review and shape the purpose, functional scope, framework, organisation structure and strategies of this new corps. The initial intent is that this Civil Emergency Corps is to be modelled along the lines of the United States Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Federal National Response Framework (NRF), but tailored to Australia’s specific needs and circumstances. The design of the organisation will be based on input received from current emergency personnel, emergency experts and from the broader Australian community. Ideas from comparable organisations overseas will also be considered, such as from nations having proven effective national civil defence organisations.

Funding is to be on par and have the same budget process as the Australian Regular Army. No more raffles, grants and fund raising. The organisation would be professionally paid, run in a military structure and discipline. Like the Army it would have core full-time regulars and a part-time reserve component. It would be initially staffed by the current people already performing emergency service work. Over time the organisation will evolve to coming up to par with the equivalent performance standards as the Army. It’s resourcing would be exponentially increased to equip it to being a national effective fighting force to deal with national emergencies, properly.

.

Essential Functions of the Civil Emergency Corps

.

- All the work of the State Emergency Services, Fire and Rescue Agencies

- Disaster Risk, Contingency, Mitigation Planning – from local to national and indeed regional scale

- Natural Disaster Response ‚fire, explosion, contamination, flood, drought, storm, sea surge, earthquake, etc

- Disaster Relief

- Disaster Recovery

- HAZMAT Response

- Disaster Management Training

- Community Education in Natural Disaster Preparation and Mitigation

- Post-disaster review an analysis and recommendations for future best practice and preparation to the Federal Government

- Ongoing national disaster research input

.

Mascot

.

Australia’s magnificent wedge-tailed eagle should be the mascot of this new organisation. It is uniquely Australian, a highly respected native bird and the eagle traditionally is a symbol for guardianship, protection, power, strength, courage, wisdom and grace. All these qualities quite apt for a Civil Emergency Corps. An appropriate motto is ‘defending our community‘ – but instead of in English or translated back to Latin, better in Australian Aboriginal.

Australia’s Wedge-Tailed Eagle

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wedge_tailed_eagle_in_flight04.jpg

Australia’s Wedge-Tailed Eagle

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wedge_tailed_eagle_in_flight04.jpg.

Incorporated into Australia’s Defence Context

1. Australian Regular Army / Army Reserve

2. Royal Australian Navy / Navy Reserve

3. Royal Australian Air Force / Air Force Reserve

4. Civil Emergency Corps / Civil Emergency Reserve

- State Corps

- Regional Brigades

- Local Units

.

.

National Government Ministry

- Minister for Civil Emergency

- Deputy Minister for Civil Emergency

- Parliamentary Secretary for Civil Emergency

.

Organisational Structure

In the same way as Australia’s three other corps are configured, the new Civil Emergency Corps is to be comprised of ‘Regulars‘ – full-time and professionally paid, as well as ‘Reservists‘, who commit on a part-time on demand basis, who are professionally trained and paid commensurate on time served.

The organisational structure is to geographically-based into a respective ‘State Corps‘ for each State and Territory, then into ‘Regional Brigades‘ and then at local level into ‘Local Units‘. Each component will have its share of regulars and reservists. The existing infrastructure of the various emergency services agencies would be utilised.

In addition, in order to deal with highly specialised functions, dedicated Corp Specialist Regiments will be established (see proposed list below).

.

A ‘National Command Centre’

- headed by the Corps General Marshall

- based in Canberra next to the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), for strategic reasons

.

State & Territory Corps

- each headed by a ‘Corp Brigadier’

- organisation structure based on a hybrid geographical model of both Fire Brigades and State Emergency Service, decided on a region by region assessment

.

Regional Brigades

- each headed by a ‘Regional Commander’

.

Local Units

- each headed by a ‘Unit Captain’

Note: Currently, in the New South Wales State Emergency Service (SES), NSW is divided into 17 ‘Regions’ based on major river systems.

‘Each of the 226 volunteer units belongs to a Region, which is led by a Region Controller. Region boundaries coincide as nearly as possible with major river systems. Each Region Controller is responsible for the operational control of emergency flood and storm responses, including planning, training, operational support and other functions within their area of control. The Region Headquarters also provides administrative support to the units in its region. The Region Headquarters all have fully functioning Operations Centres and a group of volunteers who help with training, planning, operational and other functions.’

[Source: http://www.ses.nsw.gov.au/about/ ]

.

Merger and Integration of the following national organisations into the new Civil Emergency Corps:

- Emergency Management Australia

- Care Flight Group

- Australian Volunteer Coast Guard

- St John Ambulance Service

.

.

NSW Corps

A merger and integration of the Fire and Rescue NSW, NSW Rural Fire Service, NSW Police Rescue Unit, Westpac Rescue Helicopter Service (NSW), CareFlight Group, Marine Rescue NSW, Community Emergency Services Incorporated

.

Victorian Corps

A merger and integration of the Victorian Fire Brigade, Country Fire Authority, State Emergency Service, Search and Rescue Squad (of the Victorian Police).

.

Queensland Corps

A merger and integration of the Queensland Fire and Rescue Service, Queensland State Emergency Service and Volunteer Marine Rescue, Queensland Rural Fire Service, RACQ CareFlight, Capricorn Helicopter Rescue Service (Rockhampton), Royal Flying Doctor Service, Volunteer Marine Rescue Association of Queensland.

.

South Australian Corps

A merger and integration of the South Australian Metroplitan Fire Service, Country Fire Service, State Emergency Service, South Australian Sea Rescue Squadron.

.

ACT Corps

A merger and integration of the ACT Fire Brigade, ACT State Emergency Service, ACT Rural Fire Service.

.

West Australian Corps

A merger and integration of the Fire and Emergency Services Authority of Western Australia (which has already merged its emergency service agencies), and the Volunteer Marine Rescue Western Australia.

.

Northern Territory Corps

A merger and integration of the Northern Territory Fire and Rescue Service, Northern Territory Emergency Service, Bushfire Volunteer Brigades, Rescue Co-ordination Centre (Northern Territory Transport Group).

.

Tasmanian Corps

A merger and integration of the Tasmanian Fire Service, State Emergency Service Tasmania, Tasmanian Air Rescue Trust, Sea Rescue Tasmanian Inc.

.

.

Corps Specialist Regiments

- Each specialist regiment shall have its own part-time payrolled Reserve component.

.

‘Evacuation Regiment’

- emergency field transport and logistics to effect evacuation of people and their personal effects

- assumes basic human needs provision of displaced persons (emergency accommodation, food and clothing, emergency sanitation, emergency childcare

- currently performed by charity groups like The Salvation Army, The Australian Red Cross, St Vincent de Paul Society, Anglicare Australia, Mission Australia, Catholic Mission, and others

.

‘Utilities Regiment’

- public utility repair and rebuilding – drinking water, sewage and sanitation, electricity, gas services

.

‘Reconstruction Regiment’

- debris clearance, demolition, salvage, engineering, construction, civil infrastructure, and relief housing, farm fencing repairs.

.

‘Communications Regiment’

- Corps internal communications including satellite, (attached to Army Signals), plus public communications – land phone, mobile/SMS, public broadcast services, internet services, including evacuee/missing persons database and related communications

.

‘Search and Rescue Regiment’

- assumes land search and rescue functions previously performed by various State Police special units

.

‘Maritime Regiment’

- assumes functions previously performed by Coast Guard, including sea search and rescue and vessel salvage functions

.

‘Medivac Regiment’

- assumes functions previously performed in times of disaster by State-based Ambulance Services, Royal Flying Doctior Service, Army Medics, St John Ambulance and paramedics, air-ambulance, field medicine and medical emergency evacuation, hospital transfers, disease prevention, containment and vaccinations

- Not a replacement of the State-based Ambulance Services

.

‘Community Regiment’

- provides the full range of trauma counselling, psychological and associated mental health services

.

‘Vet Regiment’

- Specialised livestock and pet recovery, animal sheltering, emergency veterinary services, emergency relief livestock agistment, stock feed provision and distribution

.

‘Biosecurity Regiment’

- All biosecurity emergency planning and response to disease outbreaks, pandemics, epidemics, pestilence, plague, national health threats or emergencies, including mass casualty events, communicable disease outbreaks, and quarantine emergency planning and response.

.

.

Civic Emergency Strategic Partners

.

- Australian Regular Army

- Engineering

- Signals (Communications)

- Logistics/Transport

- Royal Australian Navy

- Royal Australian Air Force

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Australian Government Department of health and Aging – Health Emergency

- Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation

- State and Federal Governments – Premiers Departments

- New Zealand Government – Ministry of Civil Defenc and Emergency Management CentreLink

- CSIRO

- Bushfire CRC

- Seismology Research Centre, Australia

- Geoscience Australia

- Australian Broadcasting Commission

- Department of Community Services (and State equivalents)

- Major Supermarket Retailers – Coles, Woolworths, Metcash

- Shipping Container company

- Satellite Service Provider – Australian Satellite Communications Pty Ltd,

- Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL)

- Telstra

- Qantas

- Brambles Shipping

- Salvation Army

- Red Cross

- Infrastructure Australia

- Ambulance Services

- State Hospitals

- Metcash, Coles, Woolworths

- LinFox, Toll Holdings,

- DOCS

- CentreLink

- State Morgues and Funeral Directors

- Business Council of Australia

- Small Business Council of Australia

- Insurance Council of Australia

and others.

.

Nationalisation brings serious investment.

‘The world’s biggest fire-fighting plane ejects water during a demonstration in Hahn, Germany.

The altered Boeing 747 can carry more than 75,000 litres of water. California has chartered one’.

http://i.telegraph.co.uk/telegraph/multimedia/archive/01473/jumbo-jet_1473655i.jpg

Nationalisation brings serious investment.

‘The world’s biggest fire-fighting plane ejects water during a demonstration in Hahn, Germany.

The altered Boeing 747 can carry more than 75,000 litres of water. California has chartered one’.

http://i.telegraph.co.uk/telegraph/multimedia/archive/01473/jumbo-jet_1473655i.jpg

.

.

Cost- Benefits

- Collectively across all the existing emergency organisations, Australia already spends billions in emergency management, but is not coping and is under-performing against 21st century triple bottom line expectations

- Cumulatively, Australia already spends billions in emergency management, but most of the cost is in response due to being underprepared. Prevention is better than the cure – cheaper economically and on lives.

- A professional organisation, on the payroll is fairer to the workers involved. Government reliance on community volunteers is exploitative and the standards can never collectively match full paid professionals with state of the art resourcing. Taxes are paid by the people so that government will protect them in both military and civil defence.

- A single national Corps is better positioned than multiple disjointed organisations to prepare for and respond to the ever increasing array of national disasters, but such an organisation would retain the critical advantage of regional and local personnel and resources. Economies of scale and efficiency gains from removing duplication in administration and overheads would come from a single Corps. But a key condition must be that any job losses would attract full retrenchment payouts.

- Many secondary school leavers could be readily recruited into a Civil Emergency Corps service for limited services, than are attracted to the traditional three military corps.

.

Can Australia afford it?

Can Australia afford not to? Wait until the next disaster and then ask the question again?

When Australians observe the hundreds of millions of dollars (indeed billions) of taxpayer moneys spent by State and Federal Governments in wasteful projects, the answer is a simple yes, easily. Question the opportunity cost of the following recent examples of government inappropriate spending and waste:

- Prime Minister Gillard donates $500 million to Indonesian Islamic Schools [^ November 2010]

- Senate inquiry into the Rudd-Gillard Government’s botched $300 million Green Loans program has confirmed that some groups of assessors hired as part of the program are still owed over $500,000 in fees due to mismanagement and poor administration procedures under the scheme with some assessors blasting the Federal Government for failing to implement proper checks and balances. [^July 2010]

- The Rudd Government has recorded an $850 million blow-out in the cost of its household solar power program. Labor had only intended to spend $150 million over five years on solar rebates but instead splurged $1 billion in just 18 months! [^March 2010]

- Queensland Premier Bligh committed $1.2 billion into the Tugun Desalination Plant, which has been plagued by problems since it opened last year, will be shut early next year, along with half the $380 million Bundamba treatment plant and the new $313 million plant at Gibson Island. Water infrastructure has cost Queenslanders $9 billion recently and they are entitled to know the money is being spent wisely. [^December 2010]

- Queensland Premier Anna Bligh shelved a $192 million project involving carbon capture research. Bligh has said she is determined to make carbon capture storage economically viable and has committed another $50 million of taxpayers money to finding the answer. The Bligh government has already spent $102 million researching cleaner coal technology through the state-owned ZeroGen, a joint state-commonwealth government and industry led-research project for coal-fired power production. [^December 2010]

- Victorian Premier Brumby’s Wonthaggi desalination plant will cost Victorians $15.8 billion over the next three decades, departmental figures show, leading the state opposition to accuse the government of hiding the project’s true cost. [^Sept 2010]

And disaster management it is better invested up front in prevention and response, than afterward in relief and recovery.

.

.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘Reform 03 ‘Formation of a Civil Emergency Corps‘, >Link

[2] ‘Nat MPs push levy for disaster fund‘, by Joe Kelly, The Australian, January 05, 2011,

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/treasury/nat-mps-push-levy-for-disaster-fund/story-fn59nsif-1225982479225] .[3] ‘PM Julia Gillard to help flood-hit Queensland weather storm‘, by Sean Parnell and Jared Owens, The Australian, 4th January 2011, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/pm-julia-gillard-to-help-flood-hit-queensland-weather-storm/comments-fn59niix-1225981305357

.

[5] ‘Carnarvon on flood warning but levees hold’, 20th December 2010, ABC

http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2010/12/20/3097642.htm

.

[6] ‘SA has been facing ‘very high’ fire danger’, ABC, 1st January 2011,

http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2011/01/01/3104707.htm

.

[7] Bushfires in Australia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Bushfires_in_Australia .[8] Floods in Australia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Floods_in_Australia .[9] Droughts in Australia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Droughts_in_Australia .[10] Severe Storms in Australia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Severe_storms_in_Australia .[11] Cyclones in Australia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Cyclones_in_Australia .[12] Black Saturday Bushfires

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Saturday_bushfires .[13] Earthquakes in Australia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Earthquakes_in_Australia .[14] 1997 Thredbo Landslide

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1997_Thredbo_landslide .[15] Role of the Australian Army

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Defence_Force .[16] Australian Government – Natural Disasters in Australia

http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/naturaldisasters/ .-end of article –

Emergency Management Australia (EMA) is an Australian Federal Government Agency tasked with coordinating governmental responses to emergency incidents. EMA currently sits within the Federal Attorney General’s Department.