Coal Mines: the Devil’s Dust of the Hunter Valley

Sunday, November 11th, 2012 Lessons from coal mining destruction of the Appalachian Mountains and its people

Lessons from coal mining destruction of the Appalachian Mountains and its people2010 West Virginia, United States of America

.

<<Maria Gunnoe is a community member and organizer for the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition. Here, she displays the coal dust wiped from Frankie Mooney’s garage in Twilight, West Virginia. The nearby blasting routinely fills the air with coal dust clouds, which then settle on buildings and turn air filters black. If Massey had its way, Twilight would become the next Lindytown – but Frankie’s property is closest to the company land and his refusal to sell protects the rest of Twilight from destruction.>>

[Source: ‘Stand with Coalfield Residents at Appalachia Rising‘, by ‘Carolyna’, 20100917, ^http://members.greenpeace.org/blog/carolyna/].

‘New report highlights health fears for Hunter Valley’

[New South Wales, Australia]

[Source: ‘New report highlights health fears for Hunter Valley’, 20121029, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, ^http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-10-29/new-report-highlights-health-fears-for-hunter-valley/4338446].

A Dickensian Industry

[Source: The 2012 London Olympics, ^http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/london-2012-opening-ceremony-opinion-1176668]

A Dickensian Industry

[Source: The 2012 London Olympics, ^http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/london-2012-opening-ceremony-opinion-1176668]

.

<<Health authorities are coming under pressure to properly investigate the health impacts of mining on Australia’s largest coal mining region, in the New South Wales Hunter Valley.

It comes after new research showing a link with increased death rates and disease in some other countries.

Sydney University’s Associate Professor Ruth Colagiuri analysed research from 10 countries including the USA and the UK. She says coal mining communities there had elevated rates of cancer and higher death rates from illnesses such as heart, lung and kidney disease. Birth defects were also more prevalent.

Deadly Coal Dust

Deadly Coal Dust

.

Professor Colagiuri:

- There are clear indications of serious health issues associated with coal mining and coal-fired power plants for surrounding communities. But.. there has been no such research done in the Hunter Valley.

- We have very little in Australia on the health harms at all. I guess until we have our own studies we don’t know for sure but it would be silly to think that some of the evidence is not applicable here, particularly if it’s not from the countries that are more applicable to Australia, culturally and economically.

- It is time to gather the evidence, so (that) judgments can be made…about whether the harms we’re finding in the international literature do apply to Australia.

.

The Cancer Council’s head Ian Oliver agrees: “The people who live in these areas need to be aware of whether the same thing applies here,” he said.

Sydney University’s independent research was commissioned by environmental group, Beyond Zero Emissions.

Hunter Valley Coal Train

[Source: Photo by Vince Wang

^http://www.railpage.com.au/f-t11342636-s30.htm]

Hunter Valley Coal Train

[Source: Photo by Vince Wang

^http://www.railpage.com.au/f-t11342636-s30.htm]

.

The Chairman of a Hunter Valley health lobby group has described as ‘unconscionable’ the lack of research by both State and Federal Governments into the health impacts of mining.

Dr John Drinan from the Singleton Shire Healthy Environment Group says the latest report just reinforces what Hunter mining communities have been calling for.

“It really is unconscionable that governments have allowed this sort of thing go on for years knowing full well there are implications of coal mining on health,” he said.

“Here we are in the Hunter Valley generating billions of dollars a year for the Government coffers, yet they’ve seen no need to put any effort back into finding out whether this has any deleterious impacts on our health.”

Coal mining in NSW’s Hunter region co-exists with wine growing, racehorse breeding, dairy and other pastoral industries.

[Photo by Jo Schmaltz].

Coal mining in NSW’s Hunter region co-exists with wine growing, racehorse breeding, dairy and other pastoral industries.

[Photo by Jo Schmaltz].

.

‘Research needed into Hunter’s coalmines’

[Source: ‘Research needed into Hunter’s coalmines’, by Ian Olver, The Herald (newspaper), 20121102, ^http://www.theherald.com.au/story/524537/opinion-research-needed-into-hunters-coalmines/].

Cancer Council Australia chief executive, Professor Ian Olver:

<<I did not expect the lecture room at the University of Sydney to be overflowing for the release of a report on the impact of coalmining. But it was.

The group Beyond Zero Emissions had commissioned Ruth Colaguiri’s group at the university to review all the research in Australia and overseas on the effect of coalmining on local communities. They were particularly worried about the Hunter Valley – and with reason.

.

The population of 700,000 lives in a region that has more than 30 open-cut coalmines and six coal-fired power stations.

.

As I left the launch of the report I fell into step with a person from the area. He told me his village was next to go. An open-cut mine was coming.

Dust clouds the view of the Ulan Mine conveyor belts

(North west of Mudgee, NSW)

Dust clouds the view of the Ulan Mine conveyor belts

(North west of Mudgee, NSW)

.

I asked about compensation, but, more resigned than angry, he told me that he was to receive none. He couldn’t sell, because who would buy with the mine approaching?

A mine worker for years, he would have to stick it out on his few acres growing grapes with an open-cut mine for a neighbour, located within a few kilometres.

The University of Sydney researchers reviewed 38 studies:

.

‘Data from Appalachian coalmining counties in the United States or areas in Nova Scotia, Canada, most nearly paralleled local conditions. Adults living in coalmining communities had higher rates of lung, heart and kidney disease and lung cancer. Hospitalisations for chronic lung disease increased with the amount of coal mined…’

.

Children had more asthma and higher levels of lead and cadmium in their blood. There was a higher incidence of some birth defects.

It was a similar story for those living near coal-fired power stations, with adults having a higher death rate from cancers of the lung, head, throat, bladder and a higher incidence of skin cancer and children have more breathing difficulties. They also reported more miscarriages. People living in these areas score lower on assessments of their quality of life.

Why would these illnesses occur?

Each stage of coal production – mining, transport, washing, burning the coal and disposing of the waste products – releases particles into the environment that have the potential to cause harm if the level of exposure is high and prolonged. Burning coal makes a contribution to greenhouse gases. Waste products including heavy metals have the potential to contaminate the water supply.

So what about in the Hunter Valley? Are the same health problems reported there?

We don’t know. The detailed research needed has not been done. The main thrust of the report is that we need to collect evidence so the extent of the health impact is known. Anecdotes are not sufficient. But the overseas studies give us a strong reason to push for local studies.

What we do know is that 16% of the Upper Hunter Valley consists of open cut coalmines and massive expansion is planned. It is only recently that the NSW Government has set up a network of stations to monitor particle pollution of the air. To be most valuable they will need to report each occasion when particle levels exceed acceptable limits and how frequently, rather than averages.

The report went further than documenting the health and environmental impacts of living near coalmines and coal-fired power stations. It also documented the adverse social impact on the surrounding communities.

This time there were studies from the Hunter Valley.

.

‘There is an injustice if people do not know the potential extent of the environmental damage, poor air and water quality and how it may damage their health.’

.

However, we need to know details about the levels of exposure to pollutants from mining in the Hunter and whether they are causing an increase in illness before we can ask the governments or the industry to increase protection. Communities become distressed by being disempowered and not being able to influence the changes that are reducing their living standards, and influencing their access to natural resources.

There is no doubt about the need for power production, but this needs to be balanced against harms to local communities. Diseases such as lung cancer are difficult to treat and we must seize upon any opportunity for prevention. Individual stories may raise awareness, but advocacy for change must be based on solid evidence and we must do the Australian research into the health impacts of coalmining on local communities to help us achieve a just balance.>>

.

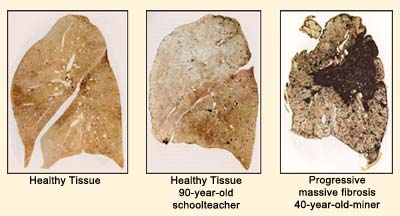

Black Lung – centuries change but Coal Dust doesn’t

<<‘Black Lung’ is a legal term describing a preventable, occupational lung disease that is contracted by prolonged breathing of Coal Mine Dust. Described by a variety of names, including:

<<‘Black Lung’ is a legal term describing a preventable, occupational lung disease that is contracted by prolonged breathing of Coal Mine Dust. Described by a variety of names, including:

- Miner’s Asthma

- Silicosis

- Coal Workers Pneumoconiosis

- Black Lung

.

.. all are all dust diseases with the same symptoms.

.

Like all occupational diseases, black lung is man-made and can be prevented. In fact, the U.S. Congress ordered Black Lung to be eradicated from the coal industry in 1969. Today, it is estimated that 1500 former coal miners each year die an agonizing death in often isolated rural communities, away from the spotlight of publicity.>>

[Source: United Mine Workers of America,^http://www.umwa.org/?q=content/black-lung].

Protesters on horseback take to the streets in November 2009 to voice concerns over the proposed Bickham coal mine (Hunter Valley)

Friends of the Earth Sydney congratulates Pages River and Tributaries Water Users Association and Rivers SoS Alliance in their successful campaign to stop the proposed Bickham open-cut coal mine and save the Pages River (near Scone in the NSW Hunter Valley).

Protesters on horseback take to the streets in November 2009 to voice concerns over the proposed Bickham coal mine (Hunter Valley)

Friends of the Earth Sydney congratulates Pages River and Tributaries Water Users Association and Rivers SoS Alliance in their successful campaign to stop the proposed Bickham open-cut coal mine and save the Pages River (near Scone in the NSW Hunter Valley).[Source: Friends of the Earth Sydney, ^http://www.sydney.foe.org.au/news/nsw-government-rejects-coal-mine-first-time-ever]

.

‘Coal industry thriving, but at what social and health cost?’

[Source: ‘Coal industry thriving, but at what social and health cost?’, by Ruth Colagiuri, Emily Morrice, The Conversation, 20121102, ^http://theconversation.edu.au/coal-industry-thriving-but-at-what-social-and-health-cost-9266].

<<If you believe industry propaganda, coal mining is a panacea not only for economic ills but also for smoothing troubled social waters. But a lack of local evidence about the health impact of the coal industry should give us all cause for thought.

With the highest density of coal mining activity close to towns and farms in Australia (well over 30 operating mines and six active coal-fired power stations, and the largest black coal exporting port in the world), many Hunter Valley residents remain unconvinced. Less than a two-hour drive north of Sydney, in one of the largest, most fertile, beautiful river valley systems in Australia, the Hunter region’s long tradition of coal mining has co-existed for many decades in balance with wine growing, racehorse breeding, dairy and other pastoral industries.

But the seemingly indiscriminate granting of mining licences by the previous state government (and little abatement likely under the current government) has put a major strain on relations between the mining industry, other local industries and the citizenry.

This is unsurprising considering inequities such as water rights favouring the coal industry over local farmers, the removal of local government input from the coal mine licensing process, and concerns about the transgenerational effects of irreparable environmental damage.

And then there’s health. Ongoing concerns and myriad anecdotal reports of serious health impacts have been expressed by both local communities and health professionals, and echoed by organisations such as Doctors for the Environment. But there’s virtually no hard evidence in the peer-reviewed literature to confirm or deny the negative health impacts on communities near coal mines or coal-fired power stations in Australia.

Such evidence is available in other countries and is summarised in a new independent report that cites 50 articles exploring the health and social harms of coal on community health from 13 countries. And it’s not pretty.

.

Health and Social Harms of Coal Mining in Local Communities:

.

Spotlight on the Hunter Region cites excess deaths from lung cancer, chronic heart, respiratory and kidney disease related to living near coal mines. The evidence is mostly from the United States and often features a dose-response effect related to coal quantity or surface area of the mine. Other effects include high blood levels of heavy metals in children, and higher rates of birth defects.

Living near coal combusting power plants is associated with excess death – in this case from lung, laryngeal and bladder cancer. Respiratory complaints, increases in non-melanoma skin cancers, still births and miscarriages are also reported.

So how alarmed should Australians be? The problem is we don’t really know. Mining methods, practices and regulatory controls vary across countries and may account for some of the reported health effects. As may factors such as difficulties in accurately measuring exposures to toxins and particulate matter in air pollution.

Despite these limitations, it would be irresponsible to ignore the possibility that some of the effects demonstrated in similar countries are likely to apply here.

The lack of local evidence in itself is alarming – particularly at a time when NSW Health is believed to be investigating a cancer cluster in the Illawarra mining region of the state. Six children living in close proximity are said to have developed either leukaemia or a lymphoma in the past five years.

A report by the Australia Institute and many other technical reports on the coal industry point out that externalities are rarely included in cost estimates of the benefits and harms of coal extraction and combustion. These factors include environmental damage, social costs such as tax subsidies to the industry (of up to $10 billion annually) and health harms estimated by the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering(ATSE) at $2.6bn annually.

Nonetheless, major developments in the coal mining industry are underway. Massive expansion of the port of Newcastle – already the world’s biggest black coal exporting port – is in planning stages. Commonly referred to as the “T4” Project, Port Waratah Coal Services propose expanding their Kooragang terminal in Newcastle in order to increase coal exports by up to 120 million tonnes a year.

CNA Coal, Muswellbrook

Hunter Valley

CNA Coal, Muswellbrook

Hunter Valley

.

Further coal port expansions are also planned by North Queensland’s Bulk Ports Corporation’s at Dudgeon Point, south of Mackay, and Rey Resources are planning their “Duchess Paradise” coal mine, which lies on a coal reserve estimated at 500 million tonnes near the Fitzroy River in the Kimberley, Western Australia.

But we have a glaring absence of local evidence to determine what impacts these projects will have on the health of surrounding communities. Surely such evidence should play a role in policy and planning of the expansion of Australia’s coal industry. It would also help us, as a society, to make up our minds about what we value more – money or our people and the planet that sustains us.>>

.

.

.

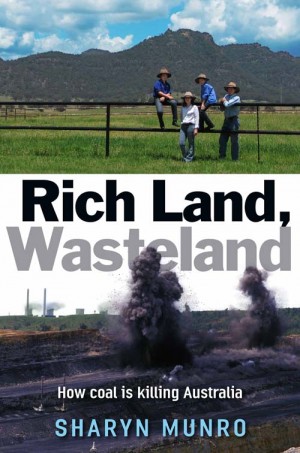

‘Coal is killing Australia’, new book reveals’

[Source: ‘Coal is killing Australia’, new book reveals’, By Christa Schwoebel, 20120527, ^http://www.greenleft.org.au/node/51154].

‘Rich Land, Wasteland’book by Sharyn Munro

Exisle Publishing & Pan Macmillan

453 pages, pb, $29.99 ^http://www.exislepublishing.com.au/Rich-Land-Wasteland.html

.

<<When a coalmine starts up near a township, a village or a farm it is to be expected that lives will change.

Indeed change is often promised and welcomed ― more Jobs, more money flowing into the community, better roads and services. In short, progress is promised.

The reality, however, is that not only do the benefits not evolve as the mines begin their operations, they destroy the land, pollute the water and air, erode people’s physical and emotional health and rip up the social fabric.

The media lead us to believe that Australia’s wellbeing depends on the mining sector. The more minerals that are exported, the healthier the Australian economy is and the better off we are. But such stories hide the real impacts of mining from most Australians.

Sharyn Munro puts aside “the diversionary cloud of spin” and tells the real story of coal mining. A resident of the upper Hunter who saw the coal mines taking over vast tracts of that valley, she spent a year travelling to the different parts of Australia where coalmining is destroying communities, livelihoods and ecosystems.

She found that “coal is killing Australia”.

Meeting victims of the industry in NSW, Queensland, Victoria, in WA and Tasmania, she records their stories. In Rich Land, Wasteland, she lets them tell their side of the story.

They tell us that there is “a war taking place in Australia”. It is an invasion where “the invaders are mostly foreign or multinational”. It looks like the second invasion of the continent.

The victims of this war, the people harassed and displaced by the mines, are fighting the invasion and mostly they have been fighting alone. They live in smaller communities or on the land, isolated from neighbours by distance and by the mines’ strategies of divide and take over.

All are deeply shocked by the lack of support from the governments and the legal system.

With their health, properties and livelihoods on the line, they try to stand up against the wealthy opponents.

The “warring sides are more unevenly matched than any David and Goliath cliche can convey”, the book says. Most of them have taken the fight up reluctantly. But if they are not despairing early on, they get increasingly incensed by the injustice they experience.

All are disillusioned, if not deeply depressed, by the failure of democratic processes.

Occasionally, they win a small concession ― only to be wiped out again by the mining companies’ blatant disregard of the conditions placed on their operations or by changed government regulations.

Where the invasion has been beaten off, as in the Margret River region in WA, the attackers regroup a short distance away, where they hope resistance will be weaker.

Each of the individual stories Munro presents is underpinned with meticulously researched facts and figures. Judiciously inserted at relevant points, these expand the anecdotal evidence into a systematic documentation of the true impact of coalmining.

In some sections, the seemingly obvious becomes a revelation.

.

Take the impact of dust:

.

From the blasting and machinery working in open cut mines, to vast piles of overburdened, uncovered coal trains up to two kilometres-long on their way to the ports and fly-ash from the coal power stations, it negatively affects the health of people, animals and plants.

The dust consists of smaller and larger particles of lead, arsenic and mercury, which are inhaled and ingested by animals and humans. Its role in higher rates of health problems such as asthma have been proven, yet the government does not act.

Contrary to the findings and advice of medical experts, governments assures residents they have nothing to fear. In 2010, the Independent Review of Cumulative Impacts on Camberwell (Hunter) “dismissed fears mines are making people sick”.

The report advised people to stay inside, close doors and wear masks, put on air-conditioners and seek medical advice.

Conditions placed on mining operations, such as to reduce dust, are hardly ever monitored ― except by the mining companies themselves. Their results never surprise.

There are many more, widely varied aspects to this war. These include issues such as ownership of mines and who benefits, the fast and huge expansions of coal mining as well as coal seam gas exploration and extraction, collusion of mine operators and government agencies, strategies applied to move people out of the way of mines, the impact of the predominantly male fly-in-fly-out workforce, higher road traffic, new exclusive rail lines and shipping in the Great Barrier Reef.

Everywhere there is environmental destruction, a lack of ― indeed the impossibility of ― site rehabilitation, and water depletion and water contamination. Everywhere, it poses the question: how can this happen in a democratic country such as Australia?

With so many details, an index would help reading and following up on some facts. The subheadings to the chapters that list locations help only to a point. I would have liked a list of acronyms and some maps.

However, when turning to the internet to look for the locations, I found that satellite maps gave extra insights into the vast onslaught of coal mines on the country.

Reading this book, veil after veil is lifted, revealing the reality of Australia today. It could be a deeply depressing book, if it weren’t for the encounters with many individuals who are standing up and speaking out.

As one says, “you must fight or nothing happens”. Munro encourages the readers to add their voices, stop the plunder and “speak up for the smart, sustainable and humane Australia we could be instead” ― the country worth fighting for.>>

.

Government vested interest in Coal Mining

‘In 2008-09 the royalty revenue generated by the NSW minerals sector was $1.28 billion, with coal accounting for approximately 95% of the total.’

[Source: New South Wales Government, Division of Resources and Energy – Minerals and Petroleum,

^http://www.resources.nsw.gov.au/resources/royalty, website accessed 20121111]

Government vested interest in Coal Mining

‘In 2008-09 the royalty revenue generated by the NSW minerals sector was $1.28 billion, with coal accounting for approximately 95% of the total.’

[Source: New South Wales Government, Division of Resources and Energy – Minerals and Petroleum,

^http://www.resources.nsw.gov.au/resources/royalty, website accessed 20121111]

.

‘Hunter coal mine fined for dust emissions‘

[Source: ‘Hunter coal mine fined for dust emissions’, by Cole Latimer, Safe To Work, 20120524, ^http://www.safetowork.com.au/news/hunter-coal-mine-fined-for-excessive-dust].

<<Rio Tinto’s Mt Thorley Warkworth coal mine has been fined by the NSW Department of Planning and Infrastructure after failing to minimise dust emissions.

A (paltry) $3000 fine was issued after an investigation into “significant dust emissions from the Mt Thorley Warkworth mine on Sunday 13 May,” the Department says.

The miner has been warned that “further breaches for dust emissions are likely to attract stronger enforcement action by the Department, including the potential for criminal proceedings in the Land and Environment Court”.

In January the mine came under fire for the placement of its water fill points, which reduced the effectiveness of the water cart fleet and its dust reduction activities.

Rio stated that this issue had been identified in 2010, and it had since secured funding to solve the problem, with the initial two fill points commissioned in December 2011, and the remaining three in February.

These new fill points are predicted to cut fill times by up to 15 minutes, while the storage capacity of each point has also been increased to enable continuous refills.

Rio stated that an early warning system for faults had been installed as well as automatic cut off.

It also received a number of noise complaints in January, accounting for 85% of submitted complaints.

According to the Department, breezes and low cloud cover contributed to noise transfer from the mines.

The Department’s executive director for major development assessment, Chris Wilson, said the mine has now failed to minimise offsite dust emissions and had not suspended or modified operations.

“Both the Upper Hunter Air Quality Network and the mine’s own real-time air quality monitor showed a spike in dust levels above the permitted 24 hour average,” Wilson said. “Our investigations have indicated that the mine’s air quality and dust mitigation measures required under the mine’s planning approval, were not adequate on that day.”

While the complaints occurred over a weekend, an officer from the nearby Singleton compliance unit was able to immediately attend the mine; Wilson adding that “the compliance officer observed that the mine was continuing to operate a dragline and excavator, despite dust being generated.

“These activities should have been suspended by the mine in the windy conditions.”

Under its existing operating approvals, the mine has to ‘implement best management practice to minimise odour, fume, and dust emissions’.

“This includes commitments by the mine to minimise wind-blown and traffic generated dust from coal handling and coal stockpiles, using water sprays on coal stockpiles to reduce airborne dust and using water trucks to minimise dust on roads. “The inspection found these commitments were not being complied with on 13 May,” Wilson said.

“Consequently large volumes of dust from mining operations flowed across the Putty road and the dust was also visible from the Golden Highway,” he added. “The decision to issue a penalty notice to the mine follows two previous warning letters last year in relation to dust.”>>

.

.

.

‘Foreign investors sow deep roots in food bowl’

[Source: ‘Foreign investors sow deep roots in food bowl’, by Leonie Lamont, Sydney Morning Herald (newspaper), 20110730, ^http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/foreign-investors-sow-deep-roots-in-food-bowl-20110729-1i4ar.html]

Sour taste … Ruby Marshall (age 12), and her sister April (age 11)

Display an anti-mining sign at their lemon stall in the former farming village of Wollar

(Photo by Peter Rae)

Sour taste … Ruby Marshall (age 12), and her sister April (age 11)

Display an anti-mining sign at their lemon stall in the former farming village of Wollar

(Photo by Peter Rae)

.

<<Mining and energy companies have bought more than 35,000 hectares of rural land in NSW in the past year, in a scramble with foreign investors in agriculture to snap up prime sites.

A Herald review of land sales found the mining interest was focused on a swath of rural land extending from the Upper Hunter through the rich Liverpool Plains to Narrabri. Mining companies spent more than $85 million buying 27,500 hectares in this area – nearly 80 per cent of the total bought.

Community agitation about the collision of farming and mining interests has risen with miners’ purchases including $14 million paid by Coalworks for Kurrumbede, the family property of poet Dorothea Mackellar, near Gunnedah.

The miners’ outlay of $113 million is challenging overseas investment in agriculture, which amounted to $125 million in the past year, buying 225,000 hectares. Despite the soaring dollar, Australia’s openness to foreign investment has made it an attractive destination for miners as well as investors and sovereign wealth funds seeking to exploit the growing demand for agricultural produce.

Chris Meares, a land agent and rural property expert, said over the past year the main ”buying power” had been institutions, corporates and mining companies – many foreign-owned.

”In the last two years, credit has got very difficult to obtain in Australia,” he said. ”Initially [after the global financial crisis] the overseas investors said the dollar was too high, but then they saw some very good investment opportunities sitting there. Commodity prices were strong and there was little opposition from Australian investors, so they could come in and buy assets globally at very cheap rates. That’s what’s happened.”

The mining boom in NSW is underpinned by prices for thermal and coking coal, which have jumped almost 60 per cent over the past five years. Export prices for liquefied natural gas – which are driving the coal seam gas boom in Queensland and NSW – have risen 36 per cent in five years and are still rising.

Mining companies said it was wrong to assume the sales meant the land was excised from agricultural use. Aston Resources said its 2800 hectares near Tamworth, which it bought for $4 million, would not be mined as it was an environmental offset – high value native trees and grassland next to the Mount Kaputar National Park, and cleared grazing land that would be leased to the original farming owner.

But Bruce Marshall, who moved to the former farming village of Wollar 20 years ago, said expansion by the mining giant Peabody Energy there had ”split the community”. Anti-mining signs adorn his fence and the fresh lemon stall run by his daughters April, 11, and Ruby, 12, beside the road to the mine site2.

This month, the NSW government set new environmental and consultative conditions for miners and extractors.

The NSW Minister for Resources and Energy, Chris Hartcher, said there had been a ”changed paradigm” that people had to acknowledge but residents and mining companies needed to know what the rules were.

”If it is essential to protect water or Prime Agricultural Land. We will not shy away from making the decision it is inappropriate [to mine] in these areas.”

The Herald used RP Data, a property information system, to review sales of more than 250 hectares during the past year. The review did not cover purchases by individuals – typically farming families – and small companies associated with them.

The biggest mining spender was Shenhua Watermark, majority owned by the Chinese government, which spent $26.5 million on 2700 hectares in the Gunnedah area. It has spent more than $200 million acquiring land for its planned $1.7 billion open-cut coal mining operation.>>

.

.

‘Cancer concern for people surrounded by coal mines’

[Source: ‘Cancer concern for people surrounded by coal mines’, by Richard Noone, The Daily Telegraph, 20121030, ^http://www.news.com.au/national/cancer-concern-for-people-surrounded-by-coal-mines/story-fndo4bst-1226505615788] . Jason and Belinda Passlow with children Harrison, Lachlan and William in Bulga (Hunter Valley)

(Photo by Waide Maguire, The Daily Telegraph)

Jason and Belinda Passlow with children Harrison, Lachlan and William in Bulga (Hunter Valley)

(Photo by Waide Maguire, The Daily Telegraph)

.

<<People surrounded by coal mines in the Hunter Valley could be at more risk of cancer, heart, lung and kidney disease and birth defects.

A new report has found serious illnesses were rife in communities near mines overseas. The report calls for an urgent health impact study in the Hunter after analysis of 50 peer-reviewed research papers from 10 countries, including the US, the UK and China, found a wide range of adverse health effects in those living close to mines.

Lead author, Sydney University associate professor Ruth Colagiuri, said similar studies in Australia’s largest coal mining region were needed “so governments and community can make informed decisions and develop policies to minimise health harms”.

The study – Health and Social Harms of Mining in Local Communities: Spotlight on the Hunter Region – was commissioned by Beyond Zero Emissions. “With plans for 30 new or bigger coal mines, an independent authority is urgently needed to monitor emissions in the region and for an in-depth health study to take place,” BZE spokesman Mark Ogge said.

Mother-of-four Belinda Passlow said her two eldest children, Eleanor, 14, and Lachlan, 10, developed asthma after moving to Bulga, a village near four open cut mines in the Upper Hunter. She said they were forced “like most people around here” to put up with constant dust.>>

.

‘Stand with Coalfield Residents at Appalachia Rising (USA)’

[Source: ‘Stand with Coalfield Residents at Appalachia Rising’, by ‘Carolyna’, Greenpeace (USA), 20100917, ^http://members.greenpeace.org/blog/carolyna/].

Appalachia Rising is three days of coalfield residents and activists from across the country standing together for an end to Mountain Top Removal (MTR), an extremely destructive form of mining where the tops of mountains are blown off to extract the coal seams below.

I saw firsthand the effects of MTR on Appalachian communities while visiting Rock Creek, West Virginia (USA) this past January. Below is a selection of photos that my friend, Phoebe Neel, and I shot while bearing witness to the destruction.

Goals Coal Plant in WV, owned by Massey Energy

Goals Coal Plant in WV, owned by Massey Energy

.

This behemoth of a complex owned by Massey Energy contains the Goals Coal Processing Plant.

Above it, sits the Shumate Coal Sludge Impoundment Pond, which contains 2.8 billion gallons of toxic coal waste. Beyond that is the Edwight Mountain Top Removal site, whose blasting puts the dam at risk of failing.

Also out of the picture is Marsh Fork Elementary, which would be wiped out if such a failure were to occur. Thankfully, the community won a six year fight this past April to build a new school, which will break ground next year.

Just realized that most of my description was for what is NOT shown in this photo. It says something when you need to be that high up to see the extent of the problem.

.

Massey Energy Notice

(Photo by Phoebe Neel)

Massey Energy Notice

(Photo by Phoebe Neel)

.

A ‘No Trespassing’ notice from Massey Energy in the rubble of a demolished house. Massey bought out the residents of Lindytown, West Virginia (USA) one by one so the company could level the town and expand the mountaintop removal site that borders it. Saying the residents had a choice in the matter is a farce – with the noise, dust, and polluted well water that comes with MTR, you trade your health for your home.

.

Demolished home in Twilight, West Virginia

Demolished home in Twilight, West Virginia

.

This is a wider shot of Lindytown, which shows three homes that have been bulldozed. Surveying the scene, I remember thinking that it could’ve been the site of a natural disaster – a storm that had decimated the neighborhood. However, this was caused by man and was just a precursor to the much wider destruction of themining to come. Nothing would be rebuilt; those concrete steps would always lead to nowhere.

The next two photos should be looked at as a pair.

Bee Tree site

(Photo by Phoebe Neel)

Bee Tree site

(Photo by Phoebe Neel)

.

This one is of the Bee Tree site in Pettus, West Virginia (USA) and the huge earth-moving machines that are used to extract the exposed coal. The striking thing about this for me is that all the rubble is refered to as “fill,” which companies like Massey dump into neighboring valleys, burying streams and polluting drinking water.

.

Brushy Fork Impoundment

(Photo by Phoebe Neel)

Brushy Fork Impoundment

(Photo by Phoebe Neel)

.

This last photo is of the Brushy Fork Impoundment, which at 8.2 billion gallons, holds much more coal waste than the Shumate Impoundment. However, it has one important thing in common – it’s also located close to an MTR site, where blasting can affect its structural integrity. It lies less than half a mile away from the Bee Tree site. Marfork Coal, a subsidary of Massey Energy, estimates a dam failure could cause a wave of coal sludge as high at 72 ft.

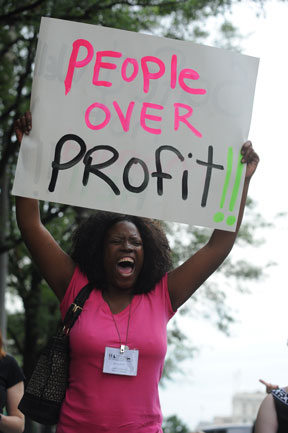

This is just a small selection of what I witnessed in West Virginia. And when you come to DC for Appalachia Rising, you won’t see any of these scarred landscapes. But what you will see are more people like Maria Gunnoe – people who refuse to give up and instead are rising up.

.

Coal Bin Flag

. Coal Dust Victim

Coal Dust Victim

.

.

‘Devil’s Dust’ – past decades of asbestos fibre exposure are being repeated with coal dust exposure

..it’s just that the law hasn’t caught up yet.

‘Devil’s Dust’ – past decades of asbestos fibre exposure are being repeated with coal dust exposure

..it’s just that the law hasn’t caught up yet.