Blue Mountains Cultural Centre uses Old Growth

Monday, November 26th, 2012 The pergola entrance to the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre

..using Old Growth ‘Tasmanian Oak’?

The pergola entrance to the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre

..using Old Growth ‘Tasmanian Oak’?

.

^Old Growth?

.

The new Blue Mountains Cultural Centre opened at 30 Parke Street, Katoomba in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney on Saturday 17th November 2012.

The Blue Mountains Cultural Centre is a very large complex for the town of Katoomba and the sparsely populated region.

It features:

- an art gallery

- state-of-the-art library

- an extensive scenic viewing platform towards the Jamison Valley (and World Heritage wilderness beyond)

- seminar room

- multi-purpose workshop

- coffee shop

- gift shop

- meeting rooms

- an interpretative centre for the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

.

It is a “purpose built cultural precinct; a place that simultaneously celebrates our unique sense of place, and allows us to explore what it means to live here, and share those understandings with those who visit our home.”

[Source: ‘Grand Opening – Blue Mountains Cultural Centre’, (special feature), Blue Mountains Gazette, 20121114, p.2].

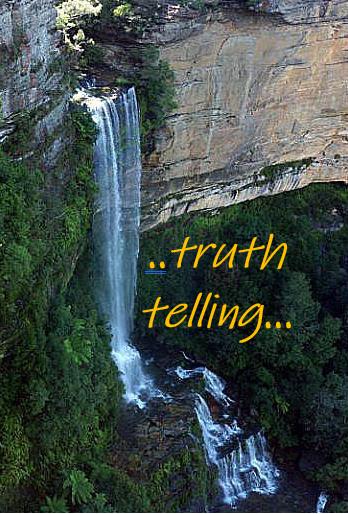

The Jamison Valley Wilderness

Contains natural stands of giant old growth Turpentines (Syncarpia glomulifera)

and old growth Mountain Blue Gums (Eucalyptus deanei

The Jamison Valley Wilderness

Contains natural stands of giant old growth Turpentines (Syncarpia glomulifera)

and old growth Mountain Blue Gums (Eucalyptus deanei.

Planning for the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre commenced way back in 1998 and there was much local community consultation in the planning process including with local Aboriginal people.

The building was commissioned by the local Blue Mountains Council and funded mainly by the New South Wales Government by more than $6 million. The Cultural Centre was designed by architects Hassell & Scott Carver Architects and built by Richard Crookes Constructions.

The Cultural Centre, now built, is positioned on the top (roof) level of a building which has, in the main, been constructed for a new relocated Coles supermarket and shopping arcade.

Blue Mountains Cultural Centre entrance

Blue Mountains Cultural Centre entrance

.

While the now operational purposes of the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre promise to have considerable merit, there are two notable drawbacks associated with the recent construction of this building, which should not be forgotten to history.

.

1. The Entrance Pergola appears to be of ‘Tasmanian Oak‘

.

.

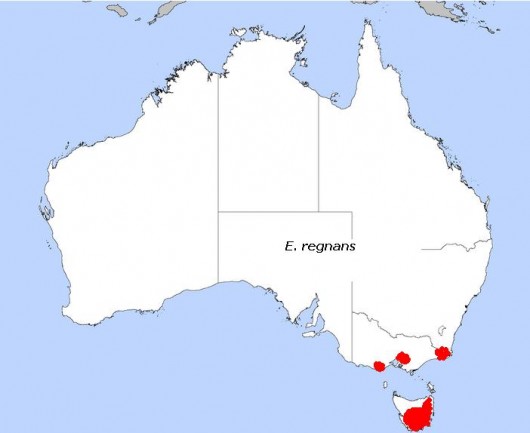

- Eucalyptus regnans

- Eucalyptus obliqua

- Eucalyptus delegatensis

The distinctive colour and texture of Tasmanian Oak (treated and stained)

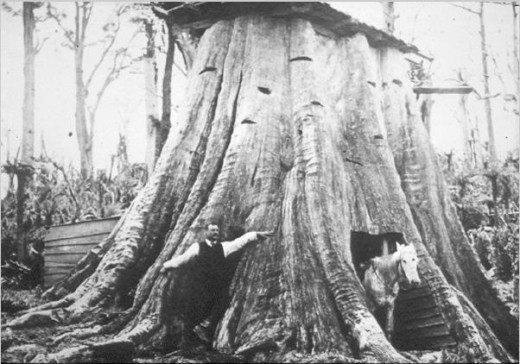

The distinctive colour and texture of Tasmanian Oak (treated and stained)These large posts and the beams have few knots and clearly have been sourced from the heartwood of very large and old native trees.

.

A ‘Tassie Oak’ comparison..

Tasmanian Oak in Tasmania

A new ten inch (wide) ‘Tasmanian Oak’ post inside Oatlands’ restored mill, Tasmania

Tasmanian Oak in Tasmania

A new ten inch (wide) ‘Tasmanian Oak’ post inside Oatlands’ restored mill, TasmaniaIt was probably from local Messmate/Stringybark (Eucalyptus obliqua), treated but not stained

(Photo by Editor, September 2009, Photo Free in Public Domain)

.

The name ‘Tasmanian Oak‘ was originally used by early European timber workers who believed the eucalypts showed the same strength as English Oak. When sourced from Tasmania, the wood is called Tasmanian Oak. When sourced from Victoria, the wood is called ‘Victorian Ash‘ or ‘Mountain Ash‘.

This uniquely Australian hardwood timber is light-coloured, ranging from straw to light reddish brown. It continues to be used in the building trade for panelling, flooring, furniture, framing, doors, stairs, external structures, joinery, reconstituted board and even as pulp for paper.

As the tallest flowering plant in the world, Eucalyptus regnans grow up to 100 metres tall. Whereas Eucalyptus delegatensis and Eucalyptus obliqua do not reach these heights; instead reaching about 70m with the tallest trees achieving 90 metres, which is no less considerable.

Read More about >Tasmanian Oak

[Source: Tasmanian Government, ^http://www.tastimber.tas.gov.au/species/pdfs/A4_ESB_Tasoak.pdf].

Nevertheless, all these species comprise timber logged from native old growth forests, not plantations. Such forests are rare and fast disappearing due to excessive logging practices – their dependent ecosystems, flora and fauna included.

The Pygmy Possum (Genus Cercartetus)

Once prolific, but now threatened across the Blue Mountains heathland escarpment

due to misguided escarpment Government Arson labelled as ‘Hazard Reduction’

To the Rural Fire Service anything natural is phobically deemed to be a ‘hazard’.

[Source: ^http://www.warra.com/warra/research_projects/research_project_WRA116.html]

The Pygmy Possum (Genus Cercartetus)

Once prolific, but now threatened across the Blue Mountains heathland escarpment

due to misguided escarpment Government Arson labelled as ‘Hazard Reduction’

To the Rural Fire Service anything natural is phobically deemed to be a ‘hazard’.

[Source: ^http://www.warra.com/warra/research_projects/research_project_WRA116.html]

.

So logging and use of this native old growth timber is unsustainable, despite Australian timber industry certification claims, which are proven dubious.

Tasmanian Oak/Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans)

Its original distribution mainly from Tasmania

To a lesser extent variants come from the high rainfall areas of East Gippsland, Dandenong Ranges to Black Spur Range and the Otway Ranges.

Tasmanian Oak/Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans)

Its original distribution mainly from Tasmania

To a lesser extent variants come from the high rainfall areas of East Gippsland, Dandenong Ranges to Black Spur Range and the Otway Ranges.

.

A likely justification for the use of Tasmanian Oak for the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre’s entrance pergola is that Tasmanian Oak being a strong hardwood timber is load-bearing with few knots. While steel or another composite material could have been used, it is probable that the Tasmanian Oak was inadertently chosen for its aesthetic appeal, ignoring sustainability criteria.

Tasmanian Oak, like many Australian native hardwood timbers, is durable, termite and borer resistant, and fire resistant which makes its suitable for such an external structure, plus it is readily available and so a comparatively affordable building material. The timber has few knots because it is sourced from old growth trees, perhaps aged over one hundred years, and so the trunk is very tall and straight between the tree’s base and the branch canopy.

The Blue Mountains are dominated by Eucalypt forests, which contain flammable natural eucalyptus oil. Although the Cultural Centre is wholly within the township of Katoomba some distance from native forests, compliance with the Building Code of Australia would have mandated the building material options for the pergola, including the requirement that the external structure be of fire resistant material. Since the Cultural Centre is situated within the least risk buffer zone of a designated Bushfire Prone Area, the choice of building material would also have would been mandated under the Australian Standard AS 3959 ‘Construction of Buildings in Bushfire Prone Areas’ and with local council’s Blue Mountains Local Environment Plan 2005 – Regulation 86 : ‘Bush fire constructions standards’.

Under AS 3959, the construction of new buildings, the use of timber as an extrenal building material is permitted in the lower risk levels provided the timber species must comply with minimum crierian for Fire Retardant Treated Timber. The following timber species have been tested and found to meet the required parameters without having to be subjected to fire retardant treatment:

- Blackbutt

- Merbau

- Red Ironbark

- River Red Gum

- Silvertop Ash

- Spotted Gum

- Turpentine

.

[Source: The Australian Timber Database, ^http://www.timber.net.au/index.php/timber-in-bushfire-prone-areas.html].

The above hardwoods are all threatened species and are disappearing fast; all Australian bar Merbau which is being depleted from old growth Indonesian rainforests.

The timber used in the Cultural Centre’s timber pergola is arguably of Tasmanian Oak, which is known variously by the common names Mountain Ash, Victorian Ash, Swamp Gum, or Stringy Gum.

It is a species of Eucalyptus native to southeastern Australia, in Tasmania and Victoria. Historically, it has been known to attain heights over 100 metres (330 ft) and is one of the tallest tree species in the world. In native forests, the two species (Mountain Ash & Alpine Ash) that are combined to produce Victorian Ash are known to be two of the world’s largest trees, occasionally growing to over 100m in height.

Yet all these Australian native hardwood timbers are increasingly becoming scarcer as they are logged for such fire-resistant application.

.

The Building Standard for Fire Retardant Treated Timber is driving deforestation of Australian Old Growth Forests.

.

These old growth timbers are the dominant canaopy species for wet eucalypt forests restricted to cool, deep soiled, mostly mountainous areas to 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) altitude with high rainfall of over 1,200 millimetres (47 in) per year. The trees grow very quickly, at more than a metre a year, and can reach 65 metres (213 ft) in 50 years, with an average life-span of 400 years.

Eucalyptus regnans is the tallest of all flowering plants, and possibly the tallest of all plants, although no living specimens can make that claim.The tallest measured living specimen, named Centurion, stands 101 metres tall in Tasmania.

Before the discovery of Centurion, the tallest known specimen was Icarus Dream, which was rediscovered in Tasmania in January, 2005 and is 97 metres (318 ft) high. It was first measured by surveyors at 98.8 metres (324 ft) in 1962 but the documentation had been lost. Sixteen living trees in Tasmania have been reliably measured in excess of 90 metres (300 ft).

Historically, the tallest individual is claimed to be the Ferguson Tree, at 132.6 metres (435 ft), found in the Watts River region of Victoria in 1871 or 1872.

Eucalyptus regnans

(marketed as ‘Tasmanian Oak’)

Eucalyptus regnans

(marketed as ‘Tasmanian Oak’)

.

The fallen logs continue supporting a rich variety of life for centuries more on the forest floor. These restricted mountain ash forests provide vital yet shrinking habitat for many of Australia’s threatened species of fauna.

.

2. Construction created considerable land fill

.

It was observed throughout the construction phase of the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre, that daily large skips of builders waste from the site were loaded alongside in Parke Street.

These commercial skips were consistently yellow in colour and the same size – about six meters long and two meters wide (12 cubic metre capacity). Typically there were two such skips positioned and loaded with builders’ waste from the construction site each weekday. This was observed over the course of a year up until August 2012. They were loaded by bobcat-style machinery with all types of mixed rubbish – concrete, unwanted insulation, scrap metal, rubble, empty cans, you name it. There was no separation of waste observed for recycling. It would all have been trucked to landfill – possibly to either the nearby Katoomba or Blaxland waste management facilities, or else off-Mountain somewhere.

Commercial skip used to cart away builders’ waste from the construction site

(Approximate scale)

Commercial skip used to cart away builders’ waste from the construction site

(Approximate scale)

.

A conservative estimate of the land fill volume generated from the Cultural Centre construction site, which also included the Coles shopping complex, over the course of the year would be 12 cubic metres x 2 skips x 5 days x 42 weeks (generously allowing for 10 non work weeks out of 52) = over 5,000 cubic metres of land fill!

.

.

Cultural Centre’s Green Credentials

.

The above two environmental impacts are far from encouraging for this high profile community-serving 21st Century building, and within a World Heritage Area to boot.

The interpretative concept is one that is meant to inspire locals and visitors alike. So these two impacts are concerning and perhaps need to be clarified in the public literature produced by the Blue Mountains Council which commissioned the Cultural Centre.

The public impression promoted by the Blue Mountains Council is that the Cultural Centre is a eco-friendly building deserving praise.

<<It has free wi-fi and features a range of green initiatives including double-glazed windows, solar panels, rainwater harvesting, and low-energy LED lights in the gallery.>>

[Source: ‘Grand Opening – Blue Mountains Cultural Centre’, (special feature), Blue Mountains Gazette, 20121114, p.3].

<<The Blue Mountains Cultural Centre has a range of green (building) features that ensure that its impacts on the World Heritage environment is kept to a minimum.

Some of the features include:

- A fully insulated roof, double-brick air cavity walls and double-glazed windows assist to insulate the building.

- Extensive rainwater collection, harvested by the Centre and the Carrington Hotel and stored onsite, in an underground 50,000 litre tank

- On the roof there are 54, 10kW solar panels to reduce the Centre’s reliance on traditional energy sources.

- The ‘green roof’ treats a portion of the Cultural Centre’s water run-off (with the aid of a UV disinfection system) that is then used for irrigation and toilet flushing.

- The Centre is lit with a combination of efficient, long-life lighting sources and lighting zoning to allow separate switching and dimming of areas adjacent to windows.

- The City Art Gallery uses LED lighting technology to significantly reduce power consumption.

- The building orientation itself is designed to provide protection to the open courtyard areas from the prevailing westerly winds and exposure to northern sunlight.

.

With these initiatives in place, the Cultural Centre aims to reduce water consumption by 5.5 million litres each year and reduce energy usage of 1.8 million kWh/year — enough energy to power 246 homes in the region.>>

[Source: Blue Mountains Cultural Centre website, ^http://bluemountainsculturalcentre.com.au/about-us/history/environmental-design-aspects/].

A core part of the Blue Mountains Council’s 25 Year Vision for the Blue Mountains region focussed on ‘Looking After the Environment‘:

<<We value our surrounding bushland and the World Heritage National Park.

Recognising that the Blue Mountains natural environment is dynamic and changing, we look after and enjoy the healthy creeks and waterways, diverse flora and fauna and clean air.

Living in harmony with the environment, we care for the ecosystems and habitats that support life in the bush and in our backyards.

We conserve energy and the natural resources we use and reduce environmental impacts by living sustainably.>>

.

[Source: ‘Towards a More Sustainable Blue Mountains – A 25 Year Vision for the City, Blue Mountains Council ,2000-2025, ^http://www.sustainablebluemountains.net.au/our-city-vision/city-vision-publications/]

.