Australia’s Owls – death from a thousand fires

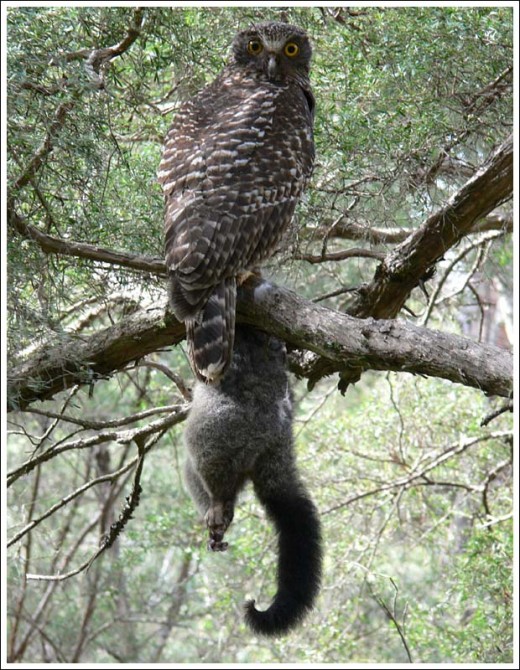

Saturday, September 3rd, 2011 Australia’s native Powerful Owl with native prey – a juvenile Brushtail Possum (2kg?)

Australia’s native Powerful Owl with native prey – a juvenile Brushtail Possum (2kg?)© Photo by Duncan Fraser ^http://www.natureofgippsland.org/

.

Powerful Owl Call

(turn on your computer volume).

.

Drought, bushfires…it’ll take years to find out what’s happened to Victoria’s Forest Owls

.

.

‘What’s happened to Victoria’s carnivorous owls? A significant number have vanished, and the (Victorian) Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) isn’t sure what’s going on.

It’s assumed the top end of the woodland food chain is either starving to death because its food source has been killed off by the drought and fires, or it is relocating to parts unknown, but it will take years to find an answer.

The DSE has been monitoring the owl populations – including that of the Powerful Owl, Australia’s largest owl – since 2000. Since then, detection rates in South Gippsland and the Bunyip State Park have dropped by half.

In some areas of the Bunyip State Park – half of which was lost to the Black Saturday fires – detections of the Sooty Owl have dropped to a third.

DSE owl specialist Ed McNabb says: ”We don’t know what’s happened to them. We can only assume that drought has played a major role. We noticed the downward trend before the fires. They’re very mobile birds, but the fires would have had an impact on their prey.”

Powerful and sooty owls, both officially listed as vulnerable, mainly eat sugar gliders and ringtail possums. The possums in particular are known to have little resistance to chronic hot weather, and their failure to thrive in the drought is the main reason why owl numbers have dropped.

While owls may have escaped (Victoria’s) Black Saturday fires, many possums would have been incinerated.

.

McNabb says the smaller carnivorous birds, such as the barking owl, are able to sustain themselves on insects. Powerful and sooty owls can also eat rabbits and birds such as magpies and kookaburras, but they need to make the change in their diet before energy loss reduces their ability to effectively hunt.

”They’ll either starve or take something else,” said McNabb.

Equally disastrous for the owls was the loss of old trees with large hollows that they require for nesting. They might have shifted elsewhere to recolonise, but this would mean taking over an already occupied territory. ”And there tends to be a home-ground advantage in these battles,” said Mr McNabb. The occupying bird has inside knowledge of the territory and a greater capacity to defend its patch, because it’s energy store will be higher. Flying great distances in search of food saps the strength from large birds and even causes them to starve.

The DSE’s biodiversity team leader for West Gippsland, Dr Rolf Willig, said:

The top order carnivores were ”an indicator species as to the well-being of the ecosystem.

Theoretically, if they’re happy, the rest are happy.”

.

For five years Dr Willig has been running a playback monitoring program in South Gippsland, where recordings of owl calls are played into the dark and answering calls are recorded. The number of birds answering calls have dropped significantly this year.

”The results indicate we may be having a delayed reaction from the fires,” he said. ”The possums not actually killed in the fires might have been exposed afterward, and the owls picked them off, eating all the food that was left.”

It will take years to find out what’s happened. ”And not just three or five years. We’ll be out here for a long time,” said Dr Willig.’

.

.

‘Conservation through Knowledge’ – a motto of leadership

The Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union is Australia’s largest non-government, non-profit, bird conservation organisation. It has sensibly branded itself as ‘Birds Australia‘, which in just two words says all that it is about, and the Emu family graphic is uniquely representative of Australia ~ the Emu being Australia’s largest bird.

Similarly sensible is its motto ‘Conservation through knowledge‘ which provides inspiration for conservation leadership, beyond Ornithology. The organisation was founded way back in 1901 to promote the study and conservation of the native bird species of Australia and adjacent regions, making it Australia’s oldest national birding association.

The Powerful Owl call above is sourced courtesy of Birds Australia.

.

.

Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua)

http://www.birdsaustralia.com.au/our-projects/powerful-owl-wbc.html

Powerful Owl (weighs under 1.5 kg)

Powerful Owl (weighs under 1.5 kg)© Photo by Duncan Fraser ^http://www.natureofgippsland.org/

.

A noctural top-order predator of tall old forests, the Powerful Owl is territorial, sedentary and monogamous ~ it calls one place home and mates for life (a lifestyle model for many humans).

.

HABITAT

Throughout most of its range this species typically inhabits open and tall wet sclerophyll forest, mainly in sheltered, densely vegetated gullies containing old-growth forest (where they breed in hollows in large trees) with a dense understorey, often near permanent streams. Such habitats are often dominated by Mountain Grey Gum, Mountain Ash, Manna Gum or Narrow-leafed Peppermint. They occasionally also occur in rainforest in gullies surrounded by sclerophyll forest or woodland. Powerful Owls also occur in adjacent open dry sclerophyll forests and woodlands, such as those dominated by box–ironbark eucalypts, Candlebark, Messmate or riparian River Red Gums; they sometimes also occur in open casuarina and cypress-pine forests.

The main food source for these owl species is hollow-dependant mammals (e.g. greater gliders, sugar gliders). Natural processes that create tree hollows typically take hundreds of years to form.

Human disturbed forests, through logging/burning/fragmentation/euphemistic ‘clearing’, destroy these vital yet rare hollow-bearing trees, and this considerably disadvantages owls.

DISTRIBUTION

- Endemic (found nowhere else on the planet, except for…) to eastern and south-eastern mainland Australia, mainly on the seaward side of the Great Divide.

.

CONSERVATION STATUS

- Vulnerable in Queensland

- Vulnerable in New South Wales

- Vulnerable in Victoria

- Endangered in South Australia

.

SURVIVAL THREATS

- Powerful Owls are adversely affected by the clearfelling of forests and the consequent conversion of those forests into open landscapes. [Deforestation]

.

When in flight, the silhouette of the Powerful Owl is distinctive, combining long, broad, rounded and deeply fingered wings with a large, sturdy body and a longish tail, gently rounded at the tip when spread. The flight is rather slow, with deep laboured wing-beats interspersed with glides.

.

.

References and Further Reading:

.

[1] The Nature of Gippsland (photographic website), ‘A photo gallery featuring the natural world of Gippsland, Victoria, Australia’, Photographs by Duncan Fraser, ^http://www.natureofgippsland.org/

[2] Birds Australia, (Special survey on Powerful Owl distribution around Sydney, 2011), ^http://birdsinbackyards.net/surveys/powerful-owl.cfm

[3] ‘Powerful Owl (Conservation) Action Statement, Victorian Government, Department of Sustainability and Environment, (1999), ^http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/103177/092_powerful_owl_1999.pdf [Read More]

[4] ‘Protecting Victoria’s Powerful Owls‘, Victorian Government, Department of Sustainability and Environment, (2001), ^http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/102144/PowerfulOwls.pdf [Read More]

.

– end of article –