Threatened Species at the whim of governments

Monday, May 20th, 2013 Orange-Bellied Parrot (Neophema chrysogaster)

Critically endangered and breeds only in Tasmania, Australia

[Source: Photo by John Harrison, in article ‘Threat of extinction demands fast and decisive action’, 20120724, by Tara Martin, published in The Conversation,

^http://theconversation.com/threat-of-extinction-demands-fast-and-decisive-action-7985]

Orange-Bellied Parrot (Neophema chrysogaster)

Critically endangered and breeds only in Tasmania, Australia

[Source: Photo by John Harrison, in article ‘Threat of extinction demands fast and decisive action’, 20120724, by Tara Martin, published in The Conversation,

^http://theconversation.com/threat-of-extinction-demands-fast-and-decisive-action-7985]

.

Government Ecological Hypocrisy

.

While Australia’s governments at federal and state level continue to allow and encourage logging, burning and mining of Australia’s native forest ecosystems, many conservationists are well aware of that the loss of these forests habitats, and other human harmful actions are driving the extinction of Australia’s flora and fauna.

Threatened species can only be saved from extinction if first their habitat is properly protected from harm. Many species such as the Orange-Bellied Parrot which has now become critically endangered require more than just habitat protection, but active recovery intervention to save it from extinction. Yet this parrot species’ native habitats restricted to southern coastal Victoria and Tasmania are actively being destroyed as if government were sadistically and callously encouraging its extinction.

In governments we trust. Yet infamously in July 2009, the man who used to belt out “And the company takes what the company wants/And nothing’s as precious as a hole in the ground”, Midnight Oil’s Peter Garrett, as then entrusted Environment Minister, approved the Beverley Four Mile Uranium Mine in South Australia.

[Source: ‘Why Peter Garrett lost his way’, August, 2009, by David Glanz ^http://www.solidarity.net.au/best/why-peter-garrett-lost-his-way/].

Beverley Four Mile Uranium Mine

550km north east of Adelaide

Beverley Four Mile Uranium Mine

550km north east of Adelaide

.

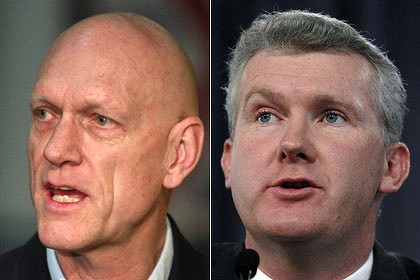

At the most senior level, the Australian Government minister who is ultimately responsible and accountable to protect Australia’s natural ecology and to prevent flora and fauna extinctions, has his environment task diluted. Tony Burke MP is currently the Minister for (1) Sustainability (2) Environment (3) Water (4) Population (5) Communities (6) the Arts, which reflects the low value that the Australian Government places on protecting Australia’s Ecology.

Australia’s recent Environment Ministers, respectively Peter Garrett and Tony Burke

Both Babyboomer Middle-Aged Men

Invariably in business, in politics, Babyboomer Middle-Aged Men

are the demographic drivers of ecological destruction across the planet.

Australia’s recent Environment Ministers, respectively Peter Garrett and Tony Burke

Both Babyboomer Middle-Aged Men

Invariably in business, in politics, Babyboomer Middle-Aged Men

are the demographic drivers of ecological destruction across the planet.

.

Tony Burke has recently approved open coal mining that will destroy the Leard State Forest in New South Wales, remnant home of the increasingly rare Koala [^Read More].

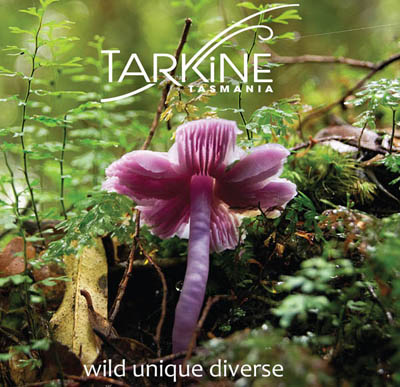

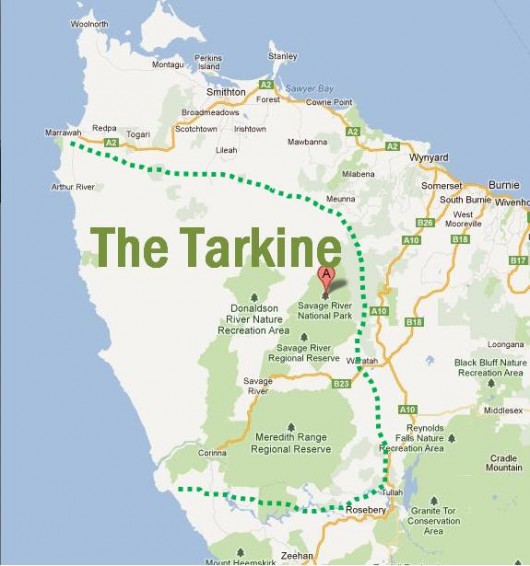

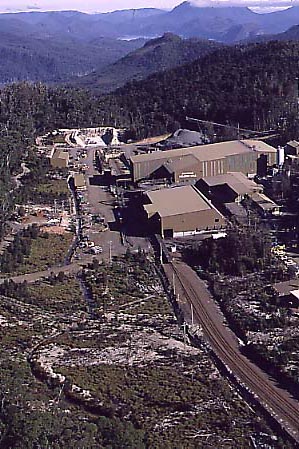

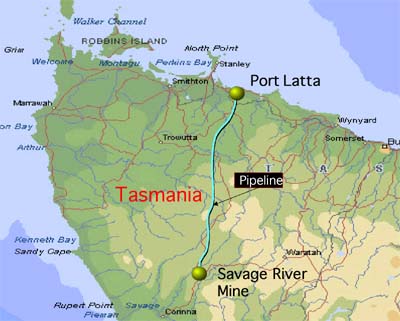

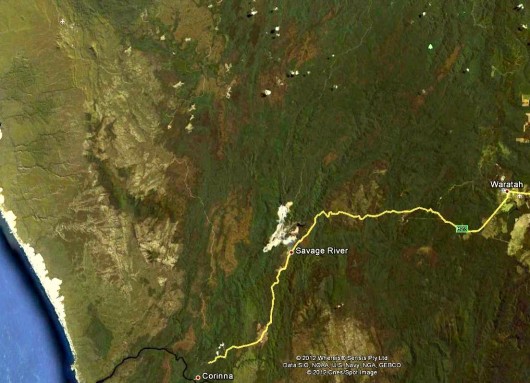

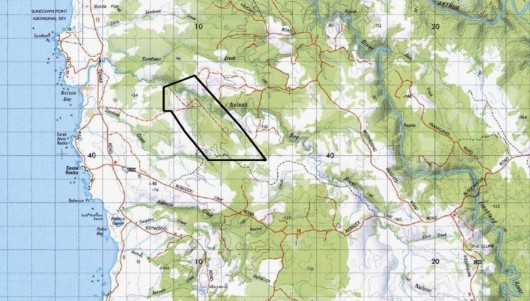

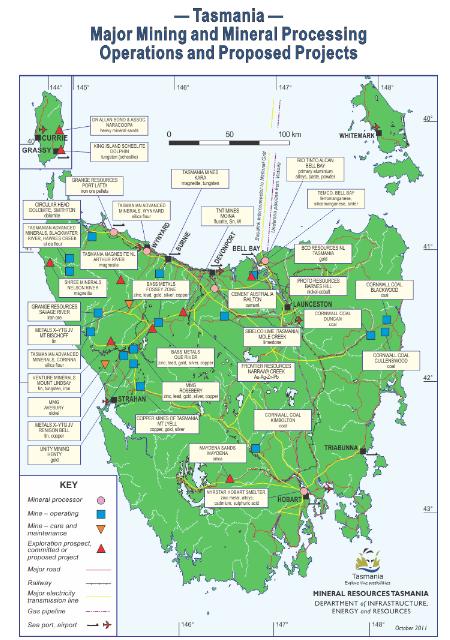

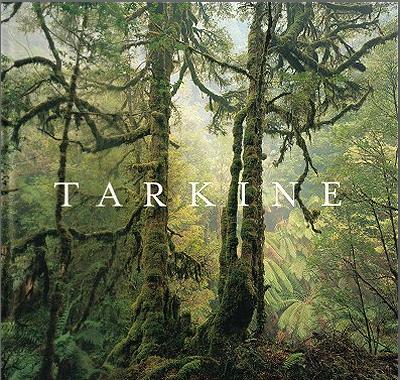

Tony Burke has approved mining in Tasmania’s Tarkine (the last continuous wilderness region of Gondwana Rainforest home to more than 60 species of rare, threatened and endangered species including the Giant Freshwater Lobster, the Wedge Tailed Eagle, the Tasmanian Devil and the Orange-bellied Parrot [^Read More].

Tony Burke has recently approved logging to continue in recognised high conservation value native forests in Tasmania, previously agreed to be protected in an Intergovernmental Agreement between the federal and Tasmanian governments in Launceston on 7th August 2011 [^Read More].

Tony Burke has recently approved port development and shipping movements through the Great Barrier Reef for Rio Tintos’ bauxite mine in western Cape York, as well as a huge new coal export terminal at Abbot Point and at dredging of Gladstone Harbour despite the ongoing damage vital marine habitat supporting endangered species including turtles, dugongs and dolphins. [^Read More]

.

“For the powerful, crimes are those that others commit.”

~ Noam Chomsky, Imperial Ambitions: Conversations on the Post-9/11 World

.

The 100 tonne coal ship the ‘Shen Neng 1’ which went aground on 5th April 2010, while negotiating the Great Barrier Reef

The ship destroyed 3km of the coral Douglas Shoal which it “completely flattened” and “pulverised” marine life. The marine park authority’s chief scientist, Dr David Wachenfeld, expressed concerned also about the toxic heavy metal anti-fouling paint scraping off the hull.

[Source: ‘Three kilometres of Great Barrier Reef damage, 20 years to mend’, 20100414, by Tom Arup, The Age newspaper,

^http://www.theage.com.au/environment/three-kilometres-of-great-barrier-reef-damage-20-years-to-mend-20100413-s7p8.html]

The 100 tonne coal ship the ‘Shen Neng 1’ which went aground on 5th April 2010, while negotiating the Great Barrier Reef

The ship destroyed 3km of the coral Douglas Shoal which it “completely flattened” and “pulverised” marine life. The marine park authority’s chief scientist, Dr David Wachenfeld, expressed concerned also about the toxic heavy metal anti-fouling paint scraping off the hull.

[Source: ‘Three kilometres of Great Barrier Reef damage, 20 years to mend’, 20100414, by Tom Arup, The Age newspaper,

^http://www.theage.com.au/environment/three-kilometres-of-great-barrier-reef-damage-20-years-to-mend-20100413-s7p8.html]

.

Threatened Species Scientific Committee

– a toothless agency abused for ecopolitical spin

.

Then, at a lower level of government, a committee has been established since 2000 to advise Australia’s Environment Minister on issues associated with Australia’s increasing list of threatened species.

The Threatened Species Scientific Committee (TSSC) is legally established for under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), which superseded the 1992 Endangered Species Protection Act. The committee’s function is to advise the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (currentky Tony Burke MP) on:

- Amendments and updating of threatened species and threatened ecological communities lists

- Key Threatening Processes

- Preparing Species Recovery Plans and Threat Abatement Plans

- Scientific input into the Species Profile and Threats Database (^SPRAT)

- Advice on the presence of hybrids in listed ecological communities

- Hold periodic workshops dealing with issues concerning Australia’s threatened species and threatened ecosystems

.

Every year the committee publishes an annual report, except it has been six years since the Australian Government published one on its website. Here is the latest report from 2006-07. [>Read 2006-07 Report.pdf , 40kb) ]

.

[Source: ‘Threatened Species Scientific Committee’, ^http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/committee.html].

Australia’s Threatened Fauna

.

As at the date of this article, the Australian Government lists the following statistics as our native fauna currently threatened with extinction to varying degrees, or now extinct.

Beware that government websites can change with whim and so the existence of the link below may disappear at any time.

.

Extinct:

- frogs (4)

- birds (23)

- mammals (27)

- other animals (1)

.

Extinct in the wild:

- fishes (1)

.

Critically Endangered:

- fishes (6)

- frogs (5)

- reptiles (4)

- birds (7)

- mammals (4)

- other animals (21)

.

Endangered:

- fishes (16)

- frogs (14)

- reptiles (16)

- birds (44)

- mammals (35)

- other animals (17)

.

Vulnerable:

- fishes (24)

- frogs (10)

- reptiles (36)

- birds (60)

- mammals (55)

- other animals (11)

.

Conservation dependent:

- fishes (4)

.

Total Threatened Fauna Species: (445)

.

[Source: Australia’s Threatened Flora, 2013, ^http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicthreatenedlist.pl].

Australia’s Critically Endangered Mammals

.

The above list is out of date, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) records are also out of date, because of the lack of diligent timely monitoring efforts by the Australian Government, and tardiness by the Australian Government in updating pertinent threatened species information back to the IUCN. Basically the Australian Government simply doesn’t care enough about Australian Ecology and dependent species about to become extinct.

It is a dire situation disgracefully detestable and sad.

According to an article in The Conversation back in December 2012, in respect to Australian mammal fauna, there are not four species deemed to be critically endangered to extinction, but now twelve, as listed below. Some of these may well be extinct such as the Christmas Island Pipistrelle..

The plight and demise of these species is not new. The Australian Government and its committees, reviews, reports and laws have confirmed this for many years. More committees, reviews, reports and laws equates to unforgiveable avoidance of moral and legal responsibility by the incumbent Environment Minister, this man:

.

Tony Burke – the only grey haired Babyboomer in this photo

His demographic is responsible for the worst destruction of ecology across the Planet,

because the Nature-compromising values of males in this generation were formed when Nature was still considered plenty and its exploitation a God-given gospel.

Tony Burke’s values are wrong, inappropriate and his powerful decisions irreversible.

Tony Burke – the only grey haired Babyboomer in this photo

His demographic is responsible for the worst destruction of ecology across the Planet,

because the Nature-compromising values of males in this generation were formed when Nature was still considered plenty and its exploitation a God-given gospel.

Tony Burke’s values are wrong, inappropriate and his powerful decisions irreversible.

.

- Woylie (Bettongia penicillata) also known as the Brush-tailed Bettong, or Brush-tailed Rat Kangaroo; a small marsupial found from south-west Western Australia across southern Australia.

- Mountain Pygmy Possum (Burramys parvus) – this tiny possum occurs as three isolated, genetically distinct populations in the alps of Victoria and NSW.

- Christmas Island Shrew (Crocidura trichura) – endemic to Christmas Island and hasn’t been seen since 1985. It is possibly extinct.

- Northern Hairy-nosed Wombat (Lasiorhinus krefftii) – approximately 200 of these wombats remain; they are limited to Epping Forest National Park (Scientific), and a reintroduced population at the Richard Underwood Nature Refuge, in Queensland.

- Lesser Stick-nest Rat (Leporillus apicalis) – this central-Australian rodent is probably extinct, with no reliable sightings since 1970.

- Bramble Cay (Melomys Melomys rubicola) – limited to a small cay in the Torres Strait, this rodent has one of the most restricted distributions of any mammal species.

- Lord Howe Long-eared Bat (Nyctophilus howensis) – known only from a single skull found in 1972, but Lord Howe Islanders continue to report bat sightings.

- Christmas Island Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi) – while listed as critically endangered, it’s generally accepted this little bat is now extinct.

- Gilbert’s Potoroo (Potorous gilbertii) – only 40 or so of these rabbit-sized marsupials live in south-west Western Australia, but the population seems stable.

- Kangaroo Island Dunnart (Sminthopsis aitkeni) – this little hand-sized marsupial is restricted to a very small area of Kangaroo Island.

- Carpentarian Rock Rat (Zyzomys palatalis) – a rodent found in sandstone gorges in the Northern Territory, there are thought to be less than 2000 remaining.

- Central Rock Rat (Zyzomys pedunculatus) – this rodent is found only in the western MacDonnell Ranges in the Northern Territory.

.

[Source: ‘Australia’s critically endangered animal species’, 20121206, by Jane Rawson, The Conversation, ^http://theconversation.com/australias-critically-endangered-animal-species-11169].

On the brink of extinction: the Bridled Nailtail Wallaby

[Source: Photo by Kate Geraghty, Dead and dying: our great mammal crisis’, 20121117, by Tim Flannery, The Age newspaper,

^http://www.theage.com.au/national/dead-and-dying-our-great-mammal-crisis-20121116-29hi9.html]

On the brink of extinction: the Bridled Nailtail Wallaby

[Source: Photo by Kate Geraghty, Dead and dying: our great mammal crisis’, 20121117, by Tim Flannery, The Age newspaper,

^http://www.theage.com.au/national/dead-and-dying-our-great-mammal-crisis-20121116-29hi9.html]

.

Leadership, Accountability, Timely Action

.

According to Tara Martin, Research Scientist at Ecosystem Sciences at the CSIRO:

<<When it comes to mammal extinctions, Australia’s track record over the last 200 years has been abysmal. Since European settlement, nearly half of the world’s mammalian extinctions have occurred in Australia – 19 at last count. So, when faced with the additional threat of climate change, how do we turn this around and ensure the trend doesn’t continue?

Learning from previous extinctions is a good place to start. A comparison between two Australian species, the recently extinct Christmas Island pipistrelle and the critically endangered but surviving orange-bellied parrot, provides some insight into the answer to this question. Namely, that acting quickly and decisively in response to evidence of rapid population decline is a key factor in determining the fate of endangered species.

.

‘Government Delay condemn a species to extinction’

A Case of Government Delay:

.

Species Extinction on Peter Garrett’s Watch

<< The Australian Government will invest $1.5 million to begin the rescue of Christmas Island’s ecosystem, including a mission to capture the last remaining Pipistrelle bats for captive breeding. “Volunteers and help from the Australasian Bat Society will be invaluable in this capture effort.” “My top priority now is to prevent any further extinctions and to restore the island’s environmental health,” Mr Garrett said.>>

A year later the critically endangered Christmas Island Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi) was declared extinct.

Species Extinction on Peter Garrett’s Watch

<< The Australian Government will invest $1.5 million to begin the rescue of Christmas Island’s ecosystem, including a mission to capture the last remaining Pipistrelle bats for captive breeding. “Volunteers and help from the Australasian Bat Society will be invaluable in this capture effort.” “My top priority now is to prevent any further extinctions and to restore the island’s environmental health,” Mr Garrett said.>>

A year later the critically endangered Christmas Island Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus murrayi) was declared extinct.[Source: ‘Christmas Island Pipistrelle Rescue’, 20090703, by Bat Conservation & Rescue Qld Inc., ^http://www.bats.org.au/?p=710]

.

<<Endemic to Christmas Island, the pipistrelle was a tiny (3.5 gram) insect-eating bat. It was first described in 1900, when numbers were widespread and abundant. In the early 1990s this began to change. The decline was rapid and the exact cause uncertain.

By 2006, experts were calling for a captive breeding program to be initiated. These pleas were ignored until 2009 when it was finally given the green light. Sadly the decision came too late, and two months (the then Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts, Peter Garrett MP) announced that the rescue attempt had failed.>>

.

A Case of Government Action (so far):

.

<<Concern about the orange-bellied parrot began in 1917, but it wasn’t until 1981 that it was confirmed to be on the brink of extinction. In an attempt to save the parrot, a multi-agency, multi-government recovery team was set up and a captive breeding program began in 1983.

Like the bat, threats to the parrot remain poorly understood. In 2010, monitoring showed that the species would become extinct in the wild within three to five years unless drastic action was taken. The recovery team immediately took action to bolster the captive population as insurance against extinction. There are currently 178 birds in captivity and less than 20 in the wild.

.

<<…How we manage endangered species ultimately comes back to the decisions made, including who makes the decisions, who is held accountable, and the timing of these decisions.

Examining these cases in the context of decision-making reveals some clear differences and highlights some important recommendations for the future management of endangered species.

One of the key differences was in the governance and leadership surrounding the two cases. Experts involved in monitoring the pipistrelle provided recommendations to government bodies, but did not have the authority to make decisions nor was there an effective leader to champion the urgent need to act. Conversely, the Orange-bellied Parrot Recovery Team had the authority to make decisions and act on them. Indeed, thanks to the Recovery Team’s broad representation, any failure to act would likely have resulted in public outcry – which raises the issue of accountability.

Management of endangered species requires tough decisions, yet they are decisions we must make. If we monitor declining populations without a process for deciding between different management options, we will only document extinctions. In some cases, the logical decision may be to employ a triage system where priority is given to species with a high likelihood of recovery. Assigning institutional accountability around the management of endangered species could help to ensure that tough decisions are made and that the processes involved are transparent.

Finally, the cases of the bat and the parrot also highlight the need to act quickly when a species is found to be on the brink of extinction. Delaying decisions only narrows our choices and removes opportunities to act. We may not always have all the answers, but this cannot be used as a reason to delay decision making. Based on a triage system a decision to not to act might be the best way forward, but if we delay the decision it becomes the only way forward.

..scientific analysis can be used to determine how much information we need to inform a good conservation decision. In the case of the Christmas Island pipistrelle, the decision to start a captive breeding program came many years too late.

By evaluating the costs, benefits, and feasibility of taking different management actions in the light of what we know about a species’ decline (or don’t know – i.e. the degree of uncertainty), it is possible to get the timing right.

Research into the methods used to stem species decline is also underway. For example, captive breeding and reintroduction programs are generally regarded as having good success rates. Further investigation into genetic management, habitat restoration, and effective techniques for reintroduction and risk management will help ensure the success of these programs for a variety of species.

Stemming the global loss of biodiversity through Species Recovery Planning will require brave decision-making in the face of uncertainty. Monitoring must be linked to decisions, institutions must be accountable for these decisions and decisions to act must be made before critical opportunities, and species, are lost forever.>>

.

[Source: ‘Threat of extinction demands fast and decisive action’, 20120724, by Tara Martin, Research Scientist, Ecosystem Sciences at CSIRO, (based on a paper by Tara Martin and with input from co-authors Mark Holdsworth, Stephen Harris, Fiona Henderson, Mark Lonsdale, in The Conversation, ^http://theconversation.com/threat-of-extinction-demands-fast-and-decisive-action-7985].

.

Principles to Properly Protect Threatened Species

.

The Australian Government is accountable for the conservation of Australia’s natutral environment and dependent species, particularly those at risk of extinction. It is charged with the democratic authority to do so and the Australian people entrust it to act responsibly. The Australian Government since 1999 had in place a national law protecting threatened species under its Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act, and since 2000 had an expert Threatened Species Scientific Committee advising it on priorities for threatened species and key threatening processes and recommended conservation actions.

But having a framework for conservation action is two steps short of the conservation action itself. Without proper funding and timely onground action, government environmental conservation is but hypocritcal lip service.

.

Gilbert’s Potoroo – only 40 left

Gilbert’s Potoroo – only 40 left

.

2008 Review of Threatened Species Protection

.

Section 522A of the EPBC Act requires it to be reviewed every 10 years from its commencement. So on 31 October 2008, Peter Garrett MP as the then Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts, commissioned an independent review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), the Australian Government’s central piece of environmental legislation.

The Terms of Reference were:

- the operation of the EPBC Act generally

- the extent to which the objects of the EPBC Act have been achieved

- the appropriateness of current matters of National Environmental Significance

- the effectiveness of the biodiversity and wildlife conservation arrangements

- Seek input from state and territory governments, members of the community and industry

.

The review to be guided by key Australian Government policy objectives:

- To promote the sustainability of Australia’s economic development to enhance individual and community well-being while protecting biological diversity and maintaining essential ecological processes and systems

- To work in partnership with the states and territories within an effective federal arrangement

- To facilitate delivery of Australia’s international obligations

- The Australian Government’s deregulation agenda to reduce and simplify the regulatory burden on people, businesses and organisations, while maintaining appropriate and efficient environmental standards

- To ensure activities under the Act represent the most appropriate, efficient and effective ways of achieving the Government’s outcomes and objectives in accordance with the Expenditure Review Principles.

.

The review was undertaken by Dr Allan Hawke (government representative) supported by a panel of experts- a retired NSW judge Paul Stein AM, Professor Mark Burgman (Environmental Science), Professor Tim Bonyhady (Environmental Law), Rosemary Warnock (ethical standards and the environment).

Community participation in the review was encouraged and 220 written submissions were received and 140 face-to-face consultation meetings were held in capital cities around Australia. An Interim Report on the review was released and a further 119 written comments were received. The Final Report was delivered to the Minister on 30 October 2009 and publicly released on 21 December 2009.

On 24 August 2011, the Minister released the Australian Government response to the independent review, three years after the review process began and about a year after the ten year review deadline.

The response centred around four key themes:

- Abandonning targeted actions to save critically endangered threatened species, and instead to vague “strategic approaches” and more plans

- Simplification of the assessment and approval processes for threatened species – vague, cheaper and less research work

- Big picture ecosystem approach

- Compromise of national standards to “harmonise” conservation approaches with the States having different priorities

.

Irrespective of the 220 written submissions and 140 face-to-face consultation meetings, out of the 71 recommendations in the Final Report, the Australian Government agreed either in part, in principle, in substance, but has since done precious little to protect Australia’s threatened species.

The review process was stipluated in the EPBC Act, but all it achieved was an opportunity for the Australian Government to undermine the 1999 standards, water down national environmental protection legislation, simplify the government’s administration and save money. Effectively the EPBC Review was a bureacratic talk fest and an expensive waste of time and taxpayer money that would have been better spent on implementing known critically endengerd species and their habitats.

The survival of Australia’s threatened species remain at the whim of federal and state governments.

What did the entire review process cost including the consultants? The amount is secret. Was it $10 million, more? The estimated cost of a Species Recovery Plans and Threat Abatement Plan to save the critically endangered Orange-bellied Parrot is how much?

Meanwhile, as few as 250 Orange-bellied Parrots remain in existence, making the species one of the most endangered species on the planet.

Meanwhile, community volunteers with The Friends of the Orange-Bellied Parrot and Wildcare Inc. in Tasmania continue to monitor the Orange-bellied Parrots during their breeding season in far southwest Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area. Members live for periods of 10 days at Birch Inlet and Melaleuca in Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area, making observations of the daily lives of the OBPs, including birds that have been bred in captivity and released at the beginning of the season as part of the Species Recovery Plan for the Orange-Bellied Parrot.

They don’t get money from the Australian Government and so have set up the Save the Orange-bellied parrot Fund. Wildcare Inc volunteers receive a small reimbursement allowance from the Tasmanian Government’s watered down Department of (1) Primary Industries, (2) Parks, (3) Water and oh yeah (4) Environment to assist with their costs.

.

[Source: Wildcare Incorporated, Tasmania, ^http://www.wildcaretas.org.au/].

>Interim Report section on Governance and Decision Making (PDF, 900kb)

.

>Interim Report section on Enforcement, Compliance, Monitoring and Audit (PDF, 600kb )

.

>Final Report (PDF, 5.3MB)

.

>Australian Government’s Response (PDF, 1MB)

.

[Source: Australian Government, ^http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/review/].

2012 Review of Threatened Species Protection

.

After the entire the EPBC Act Review process and a year after the Australian Government’s response to it, on 31 October 2012 the Australian Senate this time set up yet another review into the Effectiveness of Threatened Species and Ecological Communities’ Protection in Australia. It commissioned a Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications for enquiry and report.

This second review process came in light of the rubber stamp realisation by The Greens Senator Larissa Waters of how the Australian Government had poorly treated the EPBC Review and in light of the Auditor General report that Victoria’s environment and primary industry departments are failing to act as proper watchdogs [^Read More]. Further to that we’ve seen Professor Tim Flannery publish his opinion piece (from the Monthly’s Quarterly Essay) on the extinction crisis pointing some of the blame at the Commonwealth’s inaction [^Read More].

Public submissions were to be received by 14th December 2012 and the reporting date scheduled to be 7th February 2013, but rather late again on 14th May 2013, the Senate granted an extension of time for reporting until 20 June 2013 (one month’s time from the date of this article).

The Terms of Reference are:

(a) Management of key threats to listed species and ecological communities

(b) Development and implementation of Species Recovery Plans

[Ed: About time, and what about commensurate Threat Abatement Plans? One is ineffective without the other.]

(c) Management of critical habitat across all land tenures

(d) Regulatory and funding arrangements at all levels of government

(e) Timeliness and risk management within the listings processes

(f) The historical record of state and territory governments on these matters

(g) Any other related matter.

.

[Sources: ‘The effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection in Australia’, Terms of Reference, Australian Senate,^http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate_Committees?url=ec_ctte/threatened_species/tor.htm; ‘Threatened species in the senate spotlight’, 20121121, Councillor Samantha Dunn, Shire of Yarra Ranges, Victoria, Australia (website), ^http://crdunn.blogspot.com.au/2012/11/threatened-species-in-senate-spotlight.html].

Public submissions received by the Senate Committee

.

1 Mr Gabriel Lafitte (PDF 39KB)

2 Dr Todd Soderquist and Dr Deborah Ashworth (PDF 41KB) Attachment 1(PDF 395KB)

3 Mr Marcus Coghlan (PDF 91KB)

4 Australasian Native Orchid Society and the Australian Orchid Council (PDF 309KB)

5 Ms Fay Jones (PDF 4KB)

6 Monaro Acclimatisation Society Inc (PDF 267KB)

7 Mr James Samargis (PDF 56KB)

8 Mr Stephen Chara (PDF 432KB), Supplementary Submission(PDF 1213KB)

9 Mr Sab Lord, Lords Kakadu and Arnhemland Safaris (PDF 9KB)

10 Ms Kylie Jones (PDF 43KB)

11 East Gippsland Wildfire Taskforce Inc (PDF 1483KB)

12 Regent Honeyeater Project (PDF 9KB) Attachment 1(PDF 2946KB)

13 Mr Rob Brewster (PDF 2063KB)

14 Mr Tom Kingston (PDF 16KB)

15 Professor David Lindenmayer (PDF 44KB)

16 Mr Frank Manthey OAM, Save the Bilby Fund (PDF 189KB), Supplementary Submission(PDF 1154KB)

17 Friends of Tootgarook Wetland Reserves (PDF 390KB)

18 Mr Jim Walker (PDF 193KB)

19 Ms Harriett Swift (PDF 34KB), Supplementary Submission(PDF 11KB)

20 Island Conservation (PDF 1011KB)

21 Wildflower Society of Western Australia (Inc) (PDF 161KB)

22 Mr Daniel Bell (PDF 11KB)

23 Marie-Louise Sarjeant, Chris Sarjeant, Sonia Hutchinson, John Marsh, Maxine Jacobsen, Diana Kellett, Lesley Palma (PDF 945KB)

24 Save Tootgarook Swamp Inc (PDF 1777KB)

25 Ms Joan Spittle (PDF 83KB)

26 Mr John Jeayes (PDF 431KB)

27 Zoo and Aquarium Association (PDF 57KB)

28 Ray and Marion Lewis (PDF 239KB)

29 Mr Jean Dind (PDF 32KB)

30 Associate Professor Adrian Manning (PDF 97KB) Attachment 1(PDF 370KB), Supplementary Submission(PDF 167KB)

31 Port Campbell Community Group Inc (PDF 152KB)

32 Mr Philip Collier (PDF 790KB)

33 Mr Trevor Parton (PDF 58KB)

34 Mr Ian Wheatland, Mr Kai May, Dr Katherine Phillips and Mrs Nina Kriegisch (PDF 126KB)

35 Ms Susan M Broman (PDF 890KB)

36 Sister Marian McClelland sss (PDF 29KB)

37 Finch Society of Australia Inc (PDF 65KB)

38 Clarence Valley Conservation Coalition (PDF 250KB)

39 Ms Mary White rsm (PDF 273KB)

40 Ms Marie Hilarina Fernando (PDF 103KB)

41 Dr Emma Rooksby and Dr Keith Horton (PDF 63KB)

42 Zoos Victoria (PDF 240KB)

43 The Colong Foundation for Wilderness (PDF 376KB)

44 Mr Stewart Kerr (PDF 5KB)

45 Mr Peter Berbee (PDF 24KB)

46 Dr Andrew Burbidge (PDF 69KB)

47 Name Withheld (PDF 45KB)

48 Professor John Woinarski (PDF 157KB)

49 Ms Lee Curtis (PDF 100KB)

50 Mr Thomas Weiss (PDF 36KB)

51 Dr Peter Kyne (PDF 387KB)

52 Dr Greg P Clancy (PDF 218KB)

53 Mr Trent Patten (PDF 1536KB)

54 Ms Sabine Ritz-Kerr (PDF 47KB)

55 Dr Martine Maron (PDF 196KB)

56 Ms Claire Masters (PDF 39KB)

57 The Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists (PDF 2022KB)

58 Mr Jonathan Meddings (PDF 817KB)

59 Mr Nigel Sharp (PDF 329KB)

60 Assoc Prof Mark Lintermans (PDF 54KB)

61 Ms Pamela J W Miskin (PDF 66KB)

62 South East Forest Rescue (PDF 646KB)

63 Clarence Environment Centre (PDF 137KB)

64 Mr Craig Thomson (PDF 116KB)

65 Ms Peta Whitford (PDF 222KB)

66 Mr Daryl Dickson, Wildcard Art, Mungarru Lodge Sanctuary (PDF 269KB)

67 Ms Sera Blair (PDF 349KB)

68 Ms Kerryn Blackshaw (PDF 5KB)

69 Yarra Ranges Council (PDF 107KB)

70 Lawyers for Forests (PDF 1159KB)

71 Name Withheld (PDF 23KB)

72 Mr Greg Miles (PDF 157KB) Attachment 1(PDF 600KB) Attachment 2(PDF 4770KB)

73 Bendigo and District Environment Council, Bendigo Field Naturalists Club and Bendigo Sustainability Group (PDF 364KB) Attachment 1(PDF 173KB) Attachment 2(PDF 1923KB)

74 Dr Jasmyn Lynch (PDF 80KB)

75 Blue Mountains Conservation Society (PDF 202KB)

76 Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland (PDF 246KB)

77 CSIRO (PDF 284KB)

78 Dr Chris McGrath (PDF 245KB)

79 Mr David Blair (PDF 195KB)

80 Name Withheld (PDF 183KB)

81 WWF-Australia (PDF 553KB) Attachment 1(PDF 378KB) Attachment 2(PDF 204KB)

82 BirdLife Australia (PDF 715KB) Attachment 1(PDF 1129KB)

83 Australian Deer Association (PDF 732KB)

84 LIV Young Lawyers’ Section, Law Institute of Victoria (PDF 1209KB) Attachment 1(PDF 4436KB) Attachment 2(PDF 1303KB), Supplementary Submission(PDF 335KB)

85 Stanislaw Pelczynski and Barbara Pelczynska (PDF 245KB)

86 Friends of Grasslands (PDF 100KB)

87 Dr Kerryn Parry-Jones (PDF 239KB) Attachment 1(PDF 2143KB)

88 Humane Society International (PDF 550KB)

89 Mr Jeremy Tager (PDF 1441KB), Supplementary Submission(PDF 185KB)

90 Ms Karena Goldfinch (PDF 141KB)

91 Mr Ray Strong (PDF 95KB)

92 Healesville Environment Watch Inc, MyEnvironment Inc and Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc (PDF 2435KB)

93 Mr Ian Whitford (PDF 226KB)

94 Greenfleet (PDF 105KB)

95 Mr Barry Rowe, Candlebark Community Nursery Inc (PDF 178KB)

96 Conondale Range Committee (PDF 156KB)

97 Dr John Clulow (PDF 61KB)

98 Ms Melinda Taylor (PDF 73KB)

99 Mr David Hudson (PDF 78KB)

100 Ms Yasmin Kelsall (PDF 340KB)

101 S. Burgess and E. Bradley (PDF 61KB)

102 Ms Glenda Pickersgill (PDF 86KB)

103 Dr Tanzi Smith (PDF 249KB)

104 The Greater Mary Association Inc. (PDF 234KB)

105 Mr Philip Rance (PDF 651KB)

106 Caldera Environment Centre (PDF 416KB)

107 Mr Bruce Boyes (PDF 1505KB)

108 Australian Wildlife Health Network (PDF 418KB)

109 Friends of Hoddles Creek (PDF 1403KB)

110 Australasian Bat Society Inc (PDF 413KB)

111 Confidential

112 Confidential

113 Canberra Ornithologists Group (PDF 229KB)

114 Urban Bushland Council WA Inc (PDF 112KB)

115 MRCCC (PDF 559KB)

116 Threatened Ecosystems Network (PDF 1606KB)

117 Wildlife Disease Association Australasia (PDF 71KB)

118 Name Withheld (PDF 237KB)

119 Mr Andrew Heaver (PDF 126KB)

120 Name Withheld (PDF 76KB)

121 Ms Kate Leahy (PDF 35KB)

122 Dr Jonathan Rhodes (PDF 68KB)

123 Professor Lee Godden and Professor Jacqueline Peel (PDF 136KB) Attachment 1(PDF 123KB) Attachment 2(PDF 327KB)

124 Earth Learning Incorporated (PDF 352KB)

125 NSW Council of Freshwater Anglers (PDF 671KB)

126 Mr Mark Selmes (PDF 141KB)

127 Professor Hugh Possingham and Associate Professor Michael McCarthy (PDF 102KB)

128 Ms Susan Bendel (PDF 99KB)

129 The Wilderness Society Inc (PDF 68KB)

130 Minister for Environment and Heritage Protection Queensland (PDF 3463KB)

131 Ms Lorraine Leach (PDF 293KB)

132 Dr John Bardsley (PDF 1070KB)

133 Mr Wayne Gumley (PDF 144KB)

134 Nature Conservation Council of NSW (PDF 783KB)

135 Middle Kinglake Primary School (PDF 2301KB)

136 The Judith Eardley Save Wildlife Centre (PDF 1595KB)

137 Australian Network of Environmental Defender’s Offices Inc (PDF 214KB) Attachment 1(PDF 1129KB)

138 Ms Jenifer Johnson (PDF 1917KB)

139 Batwatch Australia (PDF 270KB)

140 Invasive Species Council (PDF 421KB)

141 Dr Rupert Baker (PDF 50KB)

142 National Parks Australia Council (PDF 331KB) Attachment 1(PDF 734KB) Attachment 2(PDF 3164KB)

143 Department of Sustainability Environment Water Population and Communities (PDF 1098KB)

144 Director of National Parks (PDF 249KB)

145 National Parks Association of NSW (PDF 196KB)

146 Mr Don Butcher (PDF 694KB)

147 Australian Conservation Foundation (PDF 725KB) Attachment 1(PDF 1129KB)

148 Australian Fisheries Management Authority (PDF 638KB)

149 Environment East Gippsland Inc. (PDF 2834KB)

150 Nature Conservation Society of South Australia (PDF 196KB)

151 Arid Lands Environment Centre (PDF 182KB)

152 Ms Prue Acton (PDF 394KB)

153 Ms Bronwyn Baade (PDF 55KB)

154 Threatened Species Scientific Committee (PDF 255KB)

155 VETO (VETO Energex Towers Organisation) (PDF 1695KB) Attachment 1(PDF 199KB)

156 Gecko – Gold Coast and Hinterland Environment Council and Save Bahrs Scrub Alliance (PDF 508KB) Attachment 1(PDF 569KB)

157 Threatened Plant Action Group (TPAG), Nature Conservation Society of South Australia (PDF 332KB)

158 FrogWatch (PDF 121KB)

159 Department of Land Resource Management, Northern Territory Government (PDF 8000KB)

160 Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland, Gold Coast and Hinterland Branch (PDF 202KB)

161 North Coast Environment Council (PDF 594KB) Attachment 1(PDF 3788KB) Attachment 2(PDF 1914KB)

162 Australian Wildlife Conservancy (PDF 400KB) Attachment 1(PDF 637KB) Attachment 2(PDF 433KB)

163 MyEnvironment Inc (PDF 6137KB)

164 South East Region Conservation Alliance Inc (PDF 3514KB)

165 Logan and Albert Conservation Association (PDF 306KB) Attachment 1(PDF 197KB) Attachment 2(PDF 147KB)

166 PGV Environmental (PDF 916KB)

167 National Farmers’ Federation (PDF 61KB)

168 Wide Bay Burnett Enviroment Council (PDF 1311KB)

169 Premier of Western Australia (PDF 14211KB)

170 Confidential

171 Confidential

172 The Wilderness Society Victoria Inc (PDF 1182KB), Response from VicForests, dated 29 January 2013(PDF 78KB)

173 Brisbane Region Environment Council (PDF 965KB)

174 North East Forest Alliance (PDF 2272KB), Response from Forestry Corporation, NSW(PDF 2036KB)

175 Eagle Junction State School (PDF 12260KB)

176 Hunter Bird Observers Club (PDF 387KB)

177 Ms Margaret Peachey (PDF 63KB)

Southern Corroborree Frog (Pseudophryne corroboree)

Endemic to yet critically endangered in the Australian Alps.

Southern Corroborree Frog (Pseudophryne corroboree)

Endemic to yet critically endangered in the Australian Alps.Its demise has been directly caused by habitat destruction from recreational 4WD use, development of ski resorts, introduced feral animals and human degradation of the frogs’ habitat. As of June 2004 it was estimated to have a population of just 64.

.

Submission #82 by BirdLife Australia

.

Australia’s leading independent conservation advocate for native birds and their habitats, BirdLife Australia, has its own Threatened Species Committee. In its submission to the review, BirdLife Australia called on Australia’s national environment law, the EPBC Act, to:

.

-

Be accountable

-

Be transparent

-

Deliver on our international commitments

-

Specify measurable ecological outcomes

-

Have a mandate to intervene on matters that are national in scope

-

Be resourced and enforced

-

Give the Australian Community a voice on national environmental matters

-

Be based on independent advice

.

Specifically these were its recommendations in detail:

.

Be accountable

.

a. The Act should require that national environmental accounts are developed (Recommendation 67), produced annually, and include Matters of National Environmental Significance (MNES). Within this the IUCN Red List Index could be used to provide a measure of performance in the threatened species protection and management.

b. The Act should establish an Independent Environment Commission to provide objective, science-based advice to the Minister to improve decision-making and ensure greater transparency and accountability (Recommendation 71). The Commission should be responsible for independent monitoring, audit, compliance and enforcement activities under the Act.

c. The Act should prescribe mandatory decision-making criteria for ecological outcomes (Recommendation 43). All actions should be legally required to maintain or improve ecological outcomes, or to demonstrate a net improvement in national environmental accounts (for each relevant MNES).

d. Regional Forest Agreements require an independent review and a more rigorous approach to auditing. A process for public input and sanctions for serious non-compliance are required. The full protections of the Act should apply to forest activities where the terms of the RFAs are not being met (Recommendation 38).

.

Be transparent

.

a. Transparency in decision-making must be maintained and improved. Current proposals do not go far enough, for example statements of reasons for all decisions made by the Minister and delegates under the Act should be released at time of the decision (Recommendation 44(1)(c)).

b. The Act must provide greater access to the courts for public interest litigation. The Government’s Rejection of Recommendations 48-53 is a key failure of the Government’s response to provide suitable checks and balances for proposals to “streamline” processes.

c. A core element of Hawke’s reform package was to provide for environmental performance audits and inquiries. The Australian Government should be subject to regular environmental performance audit under a new specialist Environmental Performance Audit Unit in the Australian National Audit Office, provided for under the Auditor-General Act 1997.

.

Deliver on our international commitments

.

a. Critical habitat must be protected, with impacts on critical habitat equated to impact on species, and consideration given to the critical habitat required under climate change (Recommendation 12 (1)). However we feel that the critical habitat register should be retained and its remit expanded.

b. The Environment Minister requires powers to develop and implement management plans to protect the values of World Heritage properties, National Heritage Places and Ramsar wetlands where the collaborative processes have not produced effective plans (Recommendation 34).

.

Specify measurable ecological outcomes

.

a. The Act should specify required ecological outcomes. This could be delivered through specified reporting periods for MNES, such as on Species Recovery Plans and Threat Abatement Plans to ensure accountability. The Government agreed the Act should include provisions that enable the auditing of environmental outcomes (performance audits) (Recommendation 61).

.

Have a mandate to intervene on matters that are national in scope

.

a. The primary object of the Act should be ‘to protect the environment’ (Recommendation 3).

b. The Act, and the way it is administered, needs to better reflect the principles of Ecological Sustainable Development (Recommendation 2).

c. The process proposed in the Government response for listing ecosystems of national significance under the Act is too restrictive and inflexible.

d. The National Reserve System should be included as a MNES.

.

Be resourced and enforced

.

a. Cost recovery mechanisms under the Act are needed to ensure that the Environment Department is adequately resourced to ensure operation of the Act and monitor performance (Recommendation 62).

b. A Reparation fund should be established (Recommendation 60). Give the Australian Community a voice on national environmental matters

a. We strongly support the creation of a call in power for ‘plans, policies and programs’ that may have a significant impact on a MNES to better deal with cumulative impacts.

.

Be based on independent advice

a. The quality of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) information needs to be substantially improved. An industry Code of Conduct for consultants supplying information for EIA and approval under the Act should be developed and the Minister, or the Environment Commission, should audit assessment information (including protected matters) to test assertions made in EIAs (Recommendation 24).

b. The Environment Commission should also be tasked with establishing a process to free consultants from their commercial dependency on proponents.

.

[Source: ‘Submission to the Australian Senate Standing Committees on Environment and Communications entitled ‘The effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection in Australia’, 20130308, by Professor Stephen Garnett(Coordinator – BirdLife Australia’s Threatened Species Committee) and Samantha Vine (Head of Conservation – BirdLife Australia, ^http://birdlife.org.au/]. . Margaret River burrowing crayfish (Engaewa pseudoreducta)

[© Photo by Quinton Burham]

With only two known populations, the Margaret River burrowing crayfish is highly endangered.

Even one of these may no longer exist, as there have been no sightings since 1985.

The threats are almost all attributed to human activity.

Land clearing is the biggest danger, as crayfish habitat can be eroded or contaminated by farming, mining and urban development.

Feral pigs also damage habitat.

[Source: ^http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/australias-most-endangered-species.htm]

Margaret River burrowing crayfish (Engaewa pseudoreducta)

[© Photo by Quinton Burham]

With only two known populations, the Margaret River burrowing crayfish is highly endangered.

Even one of these may no longer exist, as there have been no sightings since 1985.

The threats are almost all attributed to human activity.

Land clearing is the biggest danger, as crayfish habitat can be eroded or contaminated by farming, mining and urban development.

Feral pigs also damage habitat.

[Source: ^http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/australias-most-endangered-species.htm]

.

Submission #85 by our regular contributors

.

<<We acknowledge the Indigenous Nations of Australia as the traditional owners of its land and waters. We thank them for the ecological wisdom they did and continue to pass to us.

We have read and agree with the contents of the two submissions to the Committee from Marie-Louise Sarjeant, Chris Sarjeant, Sonia Hutchinson, John Marsh and Maxine Jacobson, and from Wendy Radford for BDEC, Stuart Fraser for BFNC and Sara Hill and wish to take this opportunity to register with the Committee our endorsement of them.

.

Introduction

.

<<When about 50 years ago we became involved in environmental issues, we never thought that we will be witnessing in our lifetime the degree of environmental degradation we are witnessing now.

The rate at which the degradation is now occurring is very alarming, as given that global warming and loss of biodiversity exacerbate each other, there is a real possibility that unless we act now, this positive feedback cycle will escalate beyond our ability to prevent it from resulting in the collapse of our life supporting natural ecosystems.

Over the last 20 years that we lived on a property in the forest near Bendigo we personally witnessed the progressive local extinction of the swamp wallaby due to road kills, loss of habitat to development, degradation of the Greater National Park due to fuel reduction burns and weed infestation, including invasive plants escaping from ornamental gardens, replacement of native trees in Bendigo’s streetscapes with exotics and escalation of a thriving population of Indian mynas – and all this, in spite of the biodiversity strategies, environmental protection legislations and scores of submissions, Panel and VCAT hearings.

Why is it then that we are failing to provide effective protection to our biodiversity?

In this submission we will list some of the reasons for this failure.

.

Evidence of the ineffectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection in Australia

.

The ineffectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection is evident from the Natural Heritage Trust’s “Australian Terrestrial Biodiversity Assessment 2002” report and from the successive “State of the Environment” reports which show that all the important environmental indicators are getting worse.

The reasons for this ineffectiveness is:

.

Promotion of populations growth

.

Concerns about the unsustainability of population growth and its impact on the natural environment is very well documented (Bartlett 1998, Catton 1982, Lowe 2005, p 59, Suzuki2010, pp 20 and 21) and yet population growth continues to be supported and promoted by politicians (Creighton 2012) and business, while the wide spread misconceptions about it still persist without effective challenge (Lowe 2012).

.

We submit that the Committee recommends that an ecological limit to population growth is determined and implemented into our policy and decision processes

.

Failure to recognize the role apex, or top-order, predators play in the conservation of Australia’s biodiversity

.

The failure by Euro-Australians to recognize the apex terrestrial predators function in sustaining a balance of species that is viable in the long term and in keeping the numbers down of introduced feral species, has and continues to contribute to the decline of Australia’s biodiversity and adversely affects the effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities protection.

In the case of the avian apex predator, the Wedge-tail Eagle (Aquila audax), the recognition and acceptance of its value to the environment and to farmers took number of years after CSRIO published its research results in the second half of last century.

Unfortunately, in the case of the mammalian apex predator, the dingo (Canis lupus dingo), until recent years “dingoes have rarely been studied to reach a larger understanding of our place in the Australian environment. Dingoes have mainly been studied so humans can maximize the efficacy of control efforts, capitalize on available resources and increase short-term economic gain” (Purcell 2010, p. 117), with the obvious consequent enforcement of people’s misconceptions and detrimental treatment of the dingo.

The adverse effects of the current management under the Fraser Island Dingo Management Strategy as detailed in Marie-Louise Sarjeant et al Submission of 23-11-12 to this Committee and of the mainland controls, especially by aerial baiting (Bullen 2012, Purcell 2010, p. p 3, 116, 137) on the dingo population and its culture as well as on livestock, show the urgency with which the current research (De Bias 2009, Johnson et al 2007, Purcell 2010, Wallach and O’Neill 2008, Brook et al 2012, Wallach and Johnson) needs to be taken seriously, supported by funding and implemented.

We stress here that unlike domestic dogs, cats and foxes that breed twice a year, dingoes breed only once a year, like wolfs do, are self- regulating (Purcell 2010, pp 10 and 113) and do not breed during droughts (Purcell 2010, p 24); they form small packs with hierarchical structure with only the alpha pair reproducing. The alpha pair teaches its offsprings about the packs territory and what and how to hunt, especially how to hunt kangaroos. These characteristics and not its coat colour, skull shape or genetic “purity” makes the dingo so important to Australia’s ecology (Purcell 2010, pp 39, 40, 101). Our disturbing its pack structure and culture is what causes the problem (Purcell 2010, pp3, 116,137). After all, the dingoes coexisted with Aboriginal people for thousands of years without being a problem to humans or ecology. Because their diet consists mainly of kangaroos and rabbits and not as popularly believed livestock (Purcell 2010, p 50), dingoes, like wedge-tailed eagles, are also beneficial to farmers.

We therefore submit that the Committee recommends that in order to improve the effectiveness of threatened species protection, management of key threats to listed species and of Species Recovery Rlans, the dingo needs to be reclassified as protected. New research should be funded and its findings implemented into management and a Species Recovery Plan.

We also submit that, given the Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge of the dingo, its role as the apex predator, the interdependence of species and the importance of maintaining balance (Parker 2007, Rose 1987, Rose 2000, Rose 2011), the Committee recommends that the object 3(2)(9)(iii) of the EPBCA 1999 be taken seriously and Indigenous Peoples’ role in and knowledge of the dingo and its part in the conservation of biodiversity be implemented into the management of the conservation of species and ecological communities.

.

Failure to address our cultural maladaptations, especially our culture of exuberance

.

“The culture of exuberance seemed to impute almost supernatural capabilities to Homo sapiens. It prevented us from seeing that the process of “creating our own habitat” might be a trap, the technology might come to enlarge our resource appetites instead of our world’s carrying capacity” (Catton 1982, p 122).

In the new branch of the study of human ecology, cultural maladaptation is defined as those cultural delusions, i.e. ideas and assumptions that are sheer nonsense, lending to behaviours which are equally nonsensical, which result in activities that cause a great deal of unnecessary human distress, or undesirable damage to ecosystems, or both (Boyden 2004).

Our society’s most deeply entrenched cultural maladaptation is the delusion that “humanity is apart and above natural world and in command of inexhaustible resources”. (Christie 1993)

This cultural maladaptation, or culture of exuberance, which was reinforced by our colonial expansions, technological innovations in food production, harvesting of oceans and access to minerals became the basis of our economy and as such is now fiercely defended and promoted by main stream economists, businessmen and politicians (Catton 1982) making our society more and more dependent on finite resources and responsible for the current unprecedented biodiversity crisis we now find ourselves in.

We submit that the Committee recommends that in order to make it possible to improve the effectiveness of the protection of biodiversity, this cultural maladaptation needs to be urgently addressed as “men who continue to perceive our predicament according to a pre-ecological paradigm simply will not recognize limits imposed by our world’s finiteness” (Catton 1982, p 31).

We further submit that the Committee recommends the development of a program to raise community’s awareness about both the fundamental truth, namely that “the economy is a subset of human society which, in turn, is part of the environment” (ASE 1996, p 5), as well as about the new ecological paradigm (Catton 1998, p 238), so that the most important reason for conserving biodiversity and protecting our natural environment is understood and implemented into our decision processes.

.

The dominance of economy in our decision-making processes

.

“In the short term, of course, financial considerations dominate national decision making. But behind the financial transactions there are real physical processes whose effects accumulate over long periods, and lead to serious environmental problems”. (Cocks 1996/97)

Section 3A(a) of EPBC Act 1999, provides that “decision-making processes should effectively integrate both long-term and short term economic, environmental, social and equitable considerations.”

The fundamental truth that we, the human species, are part of and therefore dependent on the environment while economy is of our making and so is part of our society and therefore dependent on both us and the environment, implies that environment needs to be given priority in our decision-making processes or alternatively, the decision-making processes need to be made subject to environmental constrains dictated by ecological sciences in the same way as they are made subject to constraints dictated by physics.

Yet the reality is that economy still continues to play dominant part in our decision-making processes. If this were the case with physics, then our buildings, houses etc would be collapsing and aeroplanes falling from the sky.

We therefore submit that the Committee recommends that in order to ensure the effectiveness of the protection of biodiversity, the decision-making processes should be given priority to the environment over economy and that such justification as “triple bottom line” and “achievement of balance” are no longer relevant in decision-making processes as the environmental bottom line has been already breached long time ago and the achievement of balance breaches it even more each time it is applied.

.

The emphasis on threatened species and ecological communities in the protection of biodiversity

.

It is now well documented that the conservation of biodiversity including threatened species and ecological communities’ protection, depends on the extent of functioning ecosystems and the ecological connectivity such as biolinks, between them (Tepper 1893, Archer 1993, Milburn 1996, Recher 1999). Yet in spite of the fact that we have cleared and fragmented the native vegetation beyond their ability to sustain their biodiversity, we place emphasis on the protection of threatened species and ecological communities while still continue to issue permits to exploit and clear land for various non-ecological purposes and economic gains.

In Victoria, we even found a way to get around the Victoria’s Biodiversity Strategy’s objective for management of biodiversity goal of ensuring that within Victoria “there is a reversal, across the entire landscape, of the long-term decline in the extent and quality of native vegetation, leading to a net gain with the target being no loss by the end 2001”, by inventing the habitat-hectare measure and designing an offsetting system which, in the case of medium and higher quality of native vegetation can be shown by simple mathematics to always lead when applied to net loss of the native vegetation’s extent.

We therefore submit that the Committee recommends that in order to improve the effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection, Prof Harry Recher’s recommended most urgent actions to “end the clearing of native vegetation, reduce grazing pressure, remove inappropriate fire regimes, control feral and native animals whose abundance threatens native species, and restore functional ecosystems, with emphasis on native vegetation, to a minimum of 30% of the landscape” be implemented (Recher 1999) and the restored ecosystems be interconnected by restoring effective biolinks.

The ending of the clearing of native vegetation is very important as it is easier to restore the habitats when remnants are present than when the land is cleared. Also the remnats provide habitat for fauna while restoration is in progress.>>

.

Conclusion

.

When we are healthy, we tend to be unaware of the presence of our organs in our bodies and of the functions they perform. Only when one of our organs fails and we have to replace its functions by artificial means do we become aware of how valuable and well performed its function was.

It seems to us that our attitude to the natural environment is the same as it is to our bodies. The air conditioner, water purifiers and desalination plants should make us aware of the value of the services our natural ecosystems provide us with (Constanza et al 1997 estimated the value of world’s ecosystem services as being more than double the global gross national product, remarking that in a sense it is infinite, as without it the economy would grind to a halt). Yet somehow we fail or refuse to see the connection. The danger is that when eventually we wake up to it, it will be too late to stop the consequences of our abuse of the environment.

It is for this reason that we have included the issue of cultural maladaptation in our submission.

Because a number of important issues, including those relating specifically to the Fraser Island’s dingo and to Bendigo region as well to the ecological reasons for rejecting COAG’s proposal for handing Federal Government’s responsibility for environmental approval to the states are covered in the two submissions to the Committee we are endorsing, we have decided not to duplicate them in our submission.

Finally we would like to draw the Committee’s attention to two books, “Legacy”(Suzuki 2010) and “Resetting the Compass”(Yencken and Wilkinson 2000, in particular chapter 13, “The four pillars of wisdom”), as they explain in a very comprehensive way the issues we have raised in our submission.>>

.

References

.

1. Alexander, N. 2009 – “Concerns heightening for Fraser Island Dingoes”; Ecos 151, Oct.-Nov., 2009, pp 18-19

2. ASE 1996 – “Australia, State of the Environment”, Executive Summery, 23 May.

3. Archer, M. Prof. 1993 – in “Expert says national parks will make mammals extinct” by Tania Ewing; The Age, 5-11-1993, p 4. (note that the title is misleading, it should be “national parks are not large enough to prevent by themselves mammal extinctions”).

4. Bartlett, A.A. 1998 – “Reflections on sustainability, Population Growth and the Environment – revisited”; www.iclahr.com/bartlett/reflections.htm

5. Boyden, S. 2004 – “The Biology of Civilization”; Ockham’s Razor, 12 December

6. Brook, L.A., Johnson, Ch.N. and Richie, E.G. 2012 – “Effects of predator control on behaviour of an apex predator and indirect consequences for mesopredator suppression”; Journal of Applied Ecology, 49: 1278-1286

7. Catton, W.R.Jr. 1982 – “Overshoot, the Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change”; University of Illinois Press

8. Christie, M.J. Dr. 1993 – “Aboriginal Science for Ecological Sustainable Future”; Australian Teachers Journal, March, no 68

9. Cocks, D. Dr. 1996/97 – in “Making tracks for the future”; Ecos 90, Summer, p 14

10. Constanza, R. et al 1997 – “The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital”; Nature, vol. 387, 15 May, pp 253 to 260

11. Creighton, A. 2012 – “People mean Growth: Turnbull”; The Australian, 3 November

12. De Blas, A. 2009 – “The Dingo’s role revitalized”; Ecos 147, Feb.-March, 2009, pp12,13;

13. Johnson, Ch. N., Isaac, J. L. and Fisher, D. O. 2007 – “Rarity of top predator triggers continent-wide collapse of mammal prey: dingoes and marsupials in Australia”; Proceedings the Royal Society, B, Biological Science (2007) 274, 341-348;

14. Lowe, I. 2005 – “A Big Fix; radical solutions for Australia’s environmental crisis”; Black Inc

15. Lowe, I. 2012 – “Australia’s population debate”; Ockham’s Razor, 19 August

16. Lowe, I. 2012 – “Bigger or Better – Australia’s Population Debate”; Uni. Of Queensland Press

17. Milburn, C. 1996 – “Native daisy sowing seeds of destruction”; The Age 11 of March

18. O’Neill, A. 2002 – “Living with the Dingo”; Envirobook ;

19. Parker, M.A. 2007 – “Bringing the Dingo Home: Discursive Representation of the Dingo by Aboriginal, Colonial and Contemporary Australians”; PhD Thesis, University of Tasmania

20. Parkhurst, J. 2010 “Vanishing Icon: the Fraser Island Dingo”; Grey Thrush Publishing;

21. Purcell, B. 2010 “Dingo”; CSIRO Publishing;

22. Rose, D.B. 1987 – “Consciousness and Responsibility in an Aboriginal Religion”; Chapter 15 in Edwards, W.H. “Traditional Aboriginal Society, a Reader”; McMillan

23. Rose, D.B. 2000 – “Dingo Makes us Human, Life and Land in an Australian Aboriginal Culture”; Cambridge Uni. Press

24. Rose, D. B. 2011 “Wild Dog Dreaming, Love and Extinction”; University of Virginia Press;

25. Suzuki, D. 2010 – “The Legacy, an Elder’s Vision for our Sustainable Future”; Allen & Unwin

26. Wallach, A. and O’Neill, A. 2008 – “Persistence of Endangered Species: Is the Dingo the Key?” Report for DEH Wildlife Conservation Fund;

27. Yencken, D. & Wilkinson, D. 2000 – “Resetting the Compass: Australia’s Journey Towards Sustainability”; CSRIO Publishing.

.

~ Submitted by Stanislaw Pelczynski and Barbara Pelczynska

.

.

“There is something fundamentally wrong with treating the earth as if it were a business in liquidation.”

~ Herman Daly