Shree Minerals invasion into the fragile Tarkine

Monday, February 27th, 2012 Shree Minerals – foreign miners pillaging Tasmania’s precious Tarkine wilderness

(Photo courtesy of Tarkine National Coalition, click photo to enlarge)

Shree Minerals – foreign miners pillaging Tasmania’s precious Tarkine wilderness

(Photo courtesy of Tarkine National Coalition, click photo to enlarge)

.

Tarkine National Coalition has described the Shree Minerals’ Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the proposed Nelson Bay River open cut iron ore mine as a mismatch of omissions, flawed assumptions and misrepresentations.

Key data on endangered orchids is missing,

and projections on impacts on Tasmanian Devil and Spotted-tailed Quoll

are based on flawed and fanciful data.

Spotted-tailed Quoll

Spotted-tailed Quoll

.

The EIS produced by the company as part of the Commonwealth environmental assessments has failed to produce a report relating to endangered and critically endangered orchid populations in the vicinity of the proposed open cut mine. The soil borne Mychorizza fungus is highly succeptible to changes in hydrology, and is essential to the germination of the area’s native orchids which cannot exist without Mychorizza. Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke included this report as a requirement in the project’s EIS guidelines issued in June 2011.

Australia’s Minister for Environment

Tony Burke

Australia’s Minister for Environment

Tony Burke

.

“Shree Minerals have decided that undertaking the necessary work on the proposal is likely to uncover some inconvenient truths, and so instead of producing scientific reports they are asking us to suspend common sense and accept that a 220 metre deep hole extending 1km long will have no impact on hydrology.” said Tarkine National Coalition spokesperson Scott Jordan.

Utter devastation

A magnetite mine at nearby Savage River

Utter devastation

A magnetite mine at nearby Savage River

.

“It’s a ridiculous notion when you consider that the mine depth will be some 170 metres below the level of the adjacent Nelson Bay River.”

TNC has also questioned the company’s motives in the clear contradictions and misrepresentations in the data relating to projections of Tasmanian devil roadkill from mine related traffic. The company has used a January-February traffic surveys as a current traffic baseline which skews the data due to the higher level of tourist, campers and shackowner during the traditional summer holiday season.

Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources (Tasmania) (DIER) data indicates that there is a doubling of vehicles on these road sections between October and January.

The company also asserted an assumed level of mine related traffic that is substantially lower than their own expert produced Traffic Impact Assessment.

The roadkill assumptions were made on an additional 82 vehicles per day in year one, and 34 vehicles per day in years 2-10, while the figures the Traffic Impact Assessment specify 122 vehicles per day in year one, and 89 vehicles per day in ongoing years.

“When you apply the expert Traffic Impact Assessment data and the DIER’s data for current road use, the increase in traffic is 329% in year one and 240% in years 2-10 which contradicts the company’s flawed projections of 89% and 34%”.

“This increase of traffic will, on the company’s formulae, result in up to 32 devil deaths per year, not the 3 per year in presented in the EIS.”

“Shree Minerals either is too incompetent to understand it’s own expert reports, or they have set out to deliberately mislead the Commonwealth and State environmental assessors.”

“Either way, they are unfit to be trusted with a Pilbara style iron ore mine in stronghold of threatened species like the Tarkine.”

The public comment period closed on Monday, and the company now has to compile public comments received and submit them with the EIS to the Commonwealth.

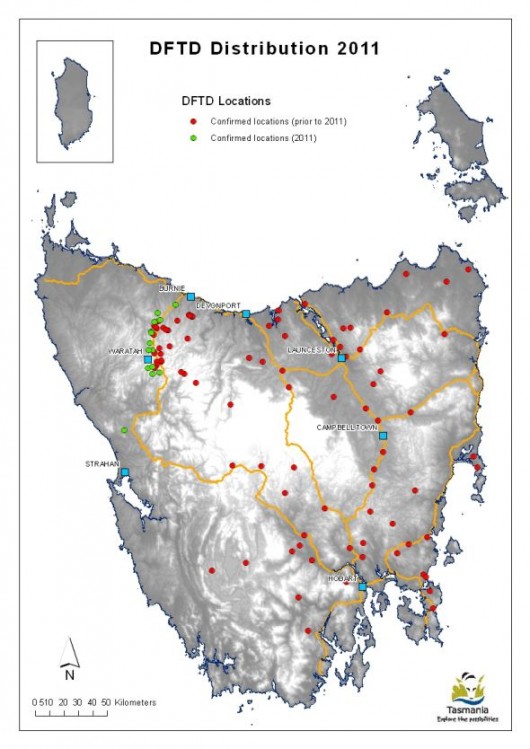

Discovery of Tasmanian devil facial tumour disease in the Tarkine

Media Release 20120224

.

Tarkine National Coalition has described the discovery of Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) at Mt Lindsay in the Tarkine as a tragedy.

“The Tarkine has been for a number of years the last bastion of disease free devils, and news that the disease has been found in the south eastern zone of the Tarkine is devastating news”, said Tarkine National Coalition spokesperson Scott Jordan.

“It is now urgent that the federal and state governments step up and take immediate action to prevent any factors that may exacerbate or accelerate the transmission of this disease to the remaining healthy populations in the Tarkine”.

“The decisions made today will have a critical impact on the survival of the Devil in the wild. Delay is no longer an option – today is the day for action.”

“They should start by reinstating the Emergency National Heritage Listing and placing an immediate halt on all mineral exploration activity in the Tarkine to allow EPBC assessments.”

.

NOTE: EPBC stands for Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

.

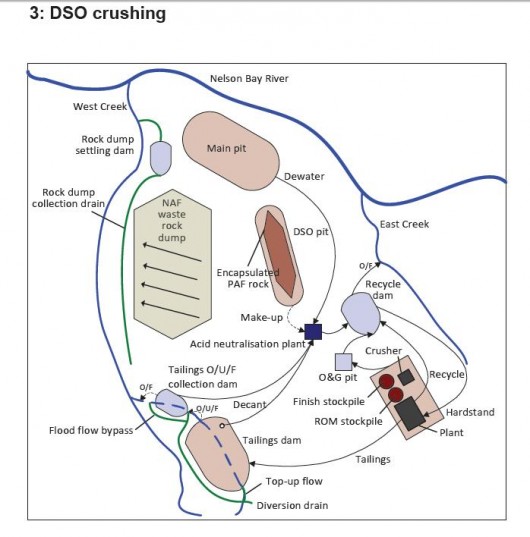

Proposed Mine Site Plan (Direct Shipping Ore) with flows to enter tributaries of Nelson River

(Source: Shree Minerals EIS, 2011)

Proposed Mine Site Plan (Direct Shipping Ore) with flows to enter tributaries of Nelson River

(Source: Shree Minerals EIS, 2011)

.

“The Nelson Bay Iron Ore Project (ELs 41/2004 & 54/2008) covers the Nelson Bay Magnetite deposit with Inferred Mineral Resources reported to Australasian Joint Ore Reserves Committee (JORC) guidelines. Drilling will look to enlarge the deposit and improve the quality of the resource, currently standing at 6.8 Million tonnes @ 38.2% magnetite at a 20% magnetite cut off. In addition exploration work will look follow up recent drilling of near surface iron oxide mineralisation in an attempt delineate direct shipping ore. Exploration of additional magnetic targets will also be undertaken.”

[Source: Shree Minerals website, ^http://www.shreeminerals.com/shreemin/scripts/page.asp?mid=16&pageid=27].

The Irreversible Ecological Damage of Long Wall Mining

.

‘Impacts of Longwall Coal Mining on The Environment‘ >Read Report (700kb)

Mining Experience in New South Wales – Waratah Rivulet

[Source: ^http://riverssos.org.au/mining-in-nsw/waratah-rivulet/].

The image belows show the shocking damage caused by longwall coal mining to the Waratah Rivulet, which flows into Woronora Dam.

Longwalls have run parallel to and directly under this once pristine waterway in the Woronora Catchment Special Area. You risk an $11,000 fine if you set foot in the Catchment without permission, yet coal companies can cause irreparable damage like this and get away with it.

Waratah Rivulet is a third order stream that is located just to the west of Helensburgh and feeds into the Woronora Dam from the south. Along with its tributaries, it makes up about 29% of the Dam catchment. The Dam provides both the Sutherland Shire and Helensburgh with drinking water. The Rivulet is within the Sydney Catchment Authority managed Woronora Special Area there is no public access without the permission of the SCA. Trespassers are liable to an $11,000 fine.

.

Longwall Mining under Waratah Rivulet

Metropolitan Colliery operates under the Woronora Special Area. Excel Coal operated it until October 2006 when Peabody Energy, the world’s largest coal mining corporation, purchased it. The method of coal extraction is longwall mining. Recent underground operations have taken place and still are taking place directly below the Waratah Rivulet and its catchment area.

In 2005 the NSW Scientific Committee declared longwall mining to be a key threatening process (read report below). The Waratah Rivulet was listed in the declaration along with several other rivers and creeks as being damaged by mining. No threat abatement plan was ever completed.

In September 2006, conservation groups were informed that serious damage to the Waratah Rivulet had taken place. Photographs were provided and an inspection was organised through the Sydney Catchment Authority (SCA) to take place on the 24th of November. On November 23rd, the Total Environment Centre met with Peabody Energy at the mining company’s request. They had heard of our forthcoming inspection and wanted to tell us about their operation and future mining plans. Through a PowerPoint presentation they told us we would be shocked by what we would see and that water had drained from the Rivulet but was reappearing further downstream closer to the dam.

The inspection took place on the 24th of November and was attended by officers from the SCA and the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC), the Total Environment Centre, Colong Foundation, Rivers SOS and two independent experts on upland swamps and sandstone geology. We walked the length of the Rivulet that flows over the longwall panels. Although, similar waterways in the area are flowing healthily, the riverbed was completely dry for much of its length. It had suffered some of the worst cracking we had ever seen as a result of longwall mining. The SCA officers indicated that at one series of pools, water levels had dropped about 3m. We were also told there is anecdotal evidence suggesting the Rivulet has ceased to pass over places never previously known to have stopped flowing.

It appeared that the whole watercourse had tilted to the east as a result of the subsidence and upsidence. Rock ledges that were once flat now sloped. Iron oxide pollution stains were also present. The SCA also told us that they did not know whether water flows were returning further downstream. There was also evidence of failed attempts at remediation with a distinctly different coloured sand having washed out of cracks and now sitting on the dry river bed or in pools.

Also undermined was Flat Rock Swamp at the southernmost extremity of the longwall panels. It is believed to be the main source of water recharge for the Waratah Rivulet. It is highly likely that the swamp has also been damaged and is sitting on a tilt.

TEC has applied under Freedom of Information legislation to the SCA for documents that refer to the damage to the Waratah Rivulet.

During the meeting with Peabody on 23rd November, the company stated its intentions sometime in 2007 to submit a 3A application under the EP&A Act 1974 (NSW) to mine a further 27 longwall panels that will run under the Rivulet and finish under the Woronora Dam storage area.

This is very alarming given the damage that has already occurred to a catchment that provides the Sutherland Shire & Helensburgh with 29% of their drinking water. The dry bed of Waratah Rivulet above the mining area and the stain of iron oxide pollution may be seen clearly through Google Earth.

.

The Bigger Picture

In 2005 Rivers SOS, a coalition of 30 groups, formed with the aim of campaigning for the NSW Government to mandate a safety zone of at least 1km around rivers and creeks threatened by mining in NSW.

The peak environment groups of NSW endorse this position and it forms part of their election policy document.

.

Longwall Mining under or close to Rivers and Streams:

.

Seven major rivers and numerous creeks in NSW have been permanently damaged by mining operations which have been allowed to go too close to, or under, riverbeds. Some rivers are used as channels for saline and acid wastewater pumped out from mines. Many more are under threat. The Minister for Primary Industries, Ian Macdonald, is continuing to approve operations with the Department of Planning and DEC also involved in the process, as are a range of agencies (EPA, Fisheries, DIPNR, SCA, etc.) on an Interagency Review Committee. This group gives recommendations concerning underground mine plans to Ian Macdonald, but has no further say in his final decision. A document recently obtained under FOI by Rivers SOS shows that an independent consultant to the Interagency Committee recommended that mining come no closer than 350m to the Cataract River, yet the Minister approved mining to come within 60m.

The damage involves multiple cracking of river bedrock, ranging from hairline cracks to cracks up to several centimetres wide, causing water loss and pollution as ecotoxic chemicals are leached from the fractured rocks.

.

Aquifers may often be breached.

.

Satisfactory remediation is not possible. In addition, rockfalls along mined river gorges are frequent. The high price of coal and the royalties gained from expanding mines are making it all too tempting for the Government to compromise the integrity of our water catchments and sacrifice natural heritage.

.

Longwall Mining in the Catchments

.

Longwall coal mining is taking place across the catchment areas south of Sydney and is also proposed in the Wyong catchment. Of particular concern is BHP-B’s huge Dendrobium mine which is undermining the Avon and Cordeaux catchments, part of Sydney’s water supply.

A story in the Sydney Morning Herald in January 2005 stated that the SCA were developing a policy for longwall coal mining within the catchments that would be ready by the middle of that year. This policy is yet to materialise.

The SMP approvals process invariably promises remediation and further monitoring. But damage to rivers continues and applications to mine areapproved with little or no significant conditions placed upon the licence.

Remediation involves grouting some cracks but cannot cover all of the cracks, many of which go undetected, in areas where the riverbed is sandy for example.

Sometimes the grout simply washes out of the crack, as is the case in the Waratah Rivulet.

The SCA was established as a result of the 1998 Sydney water crisis. Justice Peter McClellan, who led the subsequent inquiry, determined that a separate catchment management authority with teeth should be created because, as he said “someone should wake up in the morning owning the issue” of adequate management.

An audit of the SCA and the catchments in 1999 found multiple problems including understaffing, the need to interact with so many State agencies, and enormous pressure from developers. Developers in the catchments include mining companies. In spite of government policies such as SEPP 58, stating that development in catchments should have only a “neutral or beneficial effect” on water quality, longwall coal mining in the catchments have been, and are being, approved by the NSW government.

Overidden by the Mining Act 1992, the SCA appears powerless to halt the damage to Sydney’s water supply.

.

Alteration of habitat following subsidence due to longwall mining – key threatening process listing

[Source: ‘Alteration of habitat following subsidence due to longwall mining – key threatening process listing’, Dr Lesley Hughes, ChairpersonScientific Committee, Proposed Gazettal date: 15/07/05, Exhibition period: 15/07/05 – 09/09/05on Department of Environment (NSW) website,^http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/determinations/LongwallMiningKtp.htm].

NSW Scientific Committee – final determination

.

The Scientific Committee, established by the Threatened Species Conservation Act, has made a Final Determination to list Alteration of habitat following subsidence due to longwall mining as a KEY THREATENING PROCESS in Schedule 3 of the Act. Listing of key threatening processes is provided for by Part 2 of the Act.

.

The Scientific Committee has found that:

1. Longwall mining occurs in the Northern, Southern and Western Coalfields of NSW. The Northern Coalfields are centred on the Newcastle-Hunter region. The Southern Coalfield lies principally beneath the Woronora, Nepean and Georges River catchments approximately 80-120 km SSW of Sydney. Coalmines in the Western Coalfield occur along the western margin of the Sydney Basin. Virtually all coal mining in the Southern and Western Coalfields is underground mining.

2. Longwall mining involves removing a panel of coal by working a face of up to 300 m in width and up to two km long. Longwall panels are laid side by side with coal pillars, referred to as “chain pillars” separating the adjacent panels. Chain pillars generally vary in width from 20-50 m wide (Holla and Barclay 2000). The roof of the working face is temporarily held up by supports that are repositioned as the mine face advances (Karaman et al. 2001). The roof immediately above the coal seam then collapses into the void (also known as the goaf) and a collapse zone is formed above the extracted area. This zone is highly fractured and permeable and normally extends above the seam to a height of five times the extracted seam thickness (typical extracted seam thickness is approximately 2-3.5 m) (ACARP 2002). Above the collapse zone is a fractured zone where the permeability is increased to a lesser extent than in the collapse zone. The fractured zone extends to a height above the seam of approximately 20 times the seam thickness, though in weaker strata this can be as high as 30 times the seam thickness (ACARP 2002). Above this level, the surface strata will crack as a result of bending strains, with the cracks varying in size according to the level of strain, thickness of the overlying rock stratum and frequency of natural joints or planes of weakness in the strata (Holla and Barclay 2000).

3. The principal surface impact of underground coal mining is subsidence (lowering of the surface above areas that are mined) (Booth et al. 1998, Holla and Barclay 2000). The total subsidence of a surface point consists of two components, active and residual. Active subsidence, which forms 90 to 95% of the total subsidence in most cases, follows the advance of the working face and usually occurs immediately. Residual subsidence is time-dependent and is due to readjustment and compaction within the goaf (Holla and Barclay 2000). Trough-shaped subsidence profiles associated with longwall mining develop tilt between adjacent points that have subsided different amounts.

Maximum ground tilts are developed above the edges of the area of extraction and may be cumulative if more than one seam is worked up to a common boundary. The surface area affected by ground movement is greater than the area worked in the seam (Bell et al. 2000). In the NSW Southern Coalfield, horizontal displacements can extend for more than one kilometre from mine workings (and in extreme cases in excess of three km) (ACARP 2002, 2003), although at these distances, the horizontal movements have little associated tilt or strain. Subsidence at a surface point is due not only to mining in the panel directly below the point, but also to mining in the adjacent panels. It is not uncommon for mining in each panel to take a year or so and therefore a point on the surface may continue to experience residual subsidence for several years (Holla and Barclay 2000).

4. The degree of subsidence resulting from a particular mining activity depends on a number of site specific factors. Factors that affect subsidence include the design of the mine, the thickness of the coal seam being extracted, the width of the chain pillars, the ratio of the depth of overburden to the longwall panel width and the nature of the overlying strata; sandstones are known to subside less than other substrates such as shales. Subsidence is also dependent on topography, being more evident in hilly terrain than in flat or gently undulating areas (Elsworth and Liu 1995, Holla 1997, Holla and Barclay 2000, ACARP 2001). The extent and width of surface cracking over and within the vicinity of the mined goaf will also decrease with an increased depth of mining (Elsworth and Liu 1995).

5. Longwall mining can accelerate the natural process of ‘valley bulging’ (ACARP 2001, 2002). This phenomenon is indicated by an irregular upward spike in an otherwise smooth subsidence profile, generally co-inciding with the base of the valley. The spike represents a reduced amount of subsidence, known as ‘upsidence’, in the base and sides of the valley and is generally coupled with the horizontal closure of the valley sides (ACARP 2001, 2002). In most cases, the upsidence effects extend outside the valley and include the immediate cliff lines and ground beyond them (ACARP 2002).

6. Mining subsidence is frequently associated with cracking of valley floors and creeklines and with subsequent effects on surface and groundwater hydrology (Booth et al. 1998, Holla and Barclay 2000, ACARP 2001, 2002, 2003). Subsidence-induced cracks occurring beneath a stream or other surface water body may result in the loss of water to near-surface groundwater flows.

If the water body is located in an area where the coal seam is less than approximately 100-120 m below the surface, longwall mining can cause the water body to lose flow permanently. If the coal seam is deeper than approximately 150 m, the water loss may be temporary unless the area is affected by severe geological disturbances such as strong faulting. In the majority of cases, surface waters lost to the sub-surface re-emerge downstream. The ability of the water body to recover is dependent on the width of the crack, the surface gradient, the substrate composition and the presence of organic matter. An already-reduced flow rate due to drought conditions or an upstream dam or weir will increase the impact of water loss through cracking. The potential for closure of surface cracks is improved at sites with a low surface gradient although even temporary cracking, leading to loss of flow, may have long-term effects on ecological function in localised areas. The steeper the gradient, the more likely that any solids transported by water flow will be moved downstream allowing the void to remain open and the potential loss of flows to the subsurface to continue.

A lack of thick alluvium in the streambed may also prolong stream dewatering (by at least 13 years, in one case study in West Virginia, Gill 2000).

Impacts on the flows of ephemeral creeks are likely to be greater than those on permanent creeks (Holla and Barclay 2000). Cracking and subsequent water loss can result in permanent changes to riparian community structure and composition.

7. Subsidence can also cause decreased stability of slopes and escarpments, contamination of groundwater by acid drainage, increased sedimentation, bank instability and loss, creation or alteration of riffle and pool sequences, changes to flood behaviour, increased rates of erosion with associated turbidity impacts, and deterioration of water quality due to a reduction in dissolved oxygen and to increased salinity, iron oxides, manganese, and electrical conductivity (Booth et al. 1998, Booth and Bertsch 1999, Sidle et al. 2000, DLWC 2001, Gill 2000, Stout 2003). Displacement of flows may occur where water from mine workings is discharged at a point or seepage zone remote from the stream, and in some cases, into a completely different catchment. Where subsidence cracks allow surface water to mix with subsurface water, the resulting mixture may have altered chemical properties. The occurrence of iron precipitate and iron-oxidising bacteria is particularly evident in rivers where surface cracking has occurred. These bacteria commonly occur in Hawkesbury Sandstone areas, where seepage through the rock is often rich in iron compounds (Jones and Clark 1991) and are able to grow in water lacking dissolved oxygen. Where the bacteria grow as thick mats they reduce interstitial habitat, clog streams and reduce available food (DIPNR 2003). Loss of native plants and animals may occur directly via iron toxicity, or indirectly via smothering. Long-term studies in the United States indicate that reductions in diversity and abundance of aquatic invertebrates occur in streams in the vicinity of longwall mining and these effects may still be evident 12 years after mining (Stout 2003, 2004).

8. The extraction of coal and the subsequent cracking of strata surrounding the goaf may liberate methane, carbon dioxide and other gases. Most of the gas is removed by the ventilation system of the mine but some gas remains within the goaf areas. Gases tend to diffuse upwards through any cracks occurring in the strata and be emitted from the surface (ACARP 2001). Gas emissions can result in localised plant death as anaerobic conditions are created within the soil (Everett et al. 1998).

9. Subsidence due to longwall mining can destabilise cliff-lines and increase the probability of localised rockfalls and cliff collapse (Holla and Barclay 2000, ACARP 2001, 2002). This has occurred in the Western Coalfield and in some areas of the Southern Coalfield (ACARP 2001). These rockfalls have generally occurred within months of the cliffline being undermined but in some cases up to 18 years after surface cracking first became visible following mining (ACARP 2001). Changes to cliff-line topography may result in an alteration to the environment of overhangs and blowouts. These changes may result in the loss of roosts for bats and nest sites for cliff-nesting birds.

10. Damage to some creek systems in the Hunter Valley has been associated with subsidence due to longwall mining. Affected creeks include Eui Creek, Wambo Creek, Bowmans Creek, Fishery Creek and Black Creek (Dept of Sustainable Natural Resources 2003, in lit.). Damage has occurred as a result of loss of stability, with consequent release of sediment into the downstream environment, loss of stream flow, death of fringing vegetation, and release of iron rich and occasionally highly acidic leachate. In the Southern Coalfields substantial surface cracking has occurred in watercourses within the Upper Nepean, Avon, Cordeaux, Cataract, Bargo, Georges and Woronora catchments, including Flying Fox Creek, Wongawilli Creek, Native Dog Creek and Waratah Rivulet. The usual sequence of events has been subsidence-induced cracking within the streambed, followed by significant dewatering of permanent pools and in some cases complete absence of surface flow.

11. The most widely publicised subsidence event in the Southern Coalfields was the cracking of the Cataract riverbed downstream of the Broughtons Pass Weir to the confluence of the Nepean River. Mining in the vicinity began in 1988 with five longwall panels having faces of 110 m that were widened in 1992 to 155 m. In 1994, the river downstream of the longwall mining operations dried up (ACARP 2001, 2002). Water that re-emerged downstream was notably deoxygenated and heavily contaminated with iron deposits; no aquatic life was found in these areas (Everett et al. 1998). In 1998, a Mining Wardens Court Hearing concluded that 80% of the drying of the Cataract River was due to longwall mining operations, with the balance attributed to reduced flows regulated by Sydney Water. Reduction of the surface river flow was accompanied by release of gas, fish kills, iron bacteria mats, and deterioration of water quality and instream habitat. Periodic drying of the river has continued, with cessation of flow recorded on over 20 occasions between June 1999 and October 2002 (DIPNR 2003). At one site, the ‘Bubble Pool”, localised water loss up to 4 ML/day has been recorded (DIPNR 2003).

Piezometers indicated that there was an unusually high permeability in the sandstone, indicating widespread bedrock fracturing (DIPNR 2003). High gas emissions within and around areas of dead vegetation on the banks of the river have been observed and it is likely that this dieback is related to the generation of anoxic conditions in the soil as the migrating gas is oxidised (Everett et al. 1998). An attempt to rectify the cracking by grouting of the most severe crack in 1999 was only partially successful (AWT 2000). In 2001, water in the Cataract River was still highly coloured, flammable gas was still being released and flow losses of about 50% (3-3.5 ML/day) still occurring (DLWC 2001). Environmental flow releases of 1.75 ML/day in the Cataract River released from Broughtons Pass Weir were not considered enough to keep the river flowing or to maintain acceptable water quality (DIPNR 2003).

12. Subsidence associated with longwall mining has contributed to adverse effects (see below) on upland swamps. These effects have been examined in most detail on the Woronora Plateau (e.g. Young 1982, Gibbins 2003, Sydney Catchment Authority, in lit.), although functionally similar swamps exist in the Blue Mountains and on Newnes Plateau and are likely to be affected by the same processes. These swamps occur in the headwaters of the Woronora River and O’Hares Creek, both major tributaries of the Georges River, as well as major tributaries of the Nepean River, including the Cataract and Cordeaux Rivers. The swamps are exceptionally species rich with up to 70 plant species in 15 m2 (Keith and Myerscough 1993) and are habitats of particular conservation significance for their biota. The swamps occur on sandstone in valleys with slopes usually less than ten degrees in areas of shallow, impervious substrate formed by either the bedrock or clay horizons (Young and Young 1988). The low gradient, low discharge streams cannot effectively flush sediment so they lack continuous open channels and water is held in a perched water table. The swamps act as water filters, releasing water slowly to downstream creek systems thus acting to regulate water quality and flows from the upper catchment areas (Young and Young 1988).

13. Upland swamps on the Woronora Plateau are characterised by ti-tree thicket, cyperoid heath, sedgeland, restioid heath and Banksia thicket with the primary floristic variation being related to soil moisture and fertility (Young 1986, Keith and Myerscough 1993). Related swamp systems occur in the upper Blue Mountains including the Blue Mountains Sedge Swamps (also known as hanging swamps) which occur on steep valley sides below an outcropping claystone substratum and the Newnes Plateau Shrub Swamps and Coxs River Swamps which are also hydrologically dependent on the continuance of specific topographic and geological conditions (Keith and Benson 1988, Benson and Keith 1990). The swamps are subject to recurring drying and wetting, fires, erosion and partial flushing of the sediments (Young 1982, Keith 1991). The conversion of perched water table flows into subsurface flows through voids, as a result of mining-induced subsidence may significantly affect the water balance of upland swamps (eg Young and Wray 2000). The scale of this impact is currently unknown, however, changes in vegetation may not occur immediately. Over time, areas of altered hydrological regime may experience a modification to the vegetation community present, with species being favoured that prefer the new conditions. The timeframe of these changes is likely to be long-term. While subsidence may be detected and monitored within months of a mining operation, displacement of susceptible species by those suited to altered conditions is likely to extend over years to decades as the vegetation equilibrates to the new hydrological regime (Keith 1991, NPWS 2001). These impacts will be exacerbated in periods of low flow. Mine subsidence may be followed by severe and rapid erosion where warping of the swamp surface results in altered flows and surface cracking creates nick-points (Young 1982). Fire regimes may also be altered, as dried peaty soils become oxidised and potentially flammable (Sydney Catchment Authority, in lit.) (Kodela et al. 2001).

14. The upland swamps of the Woronora Plateau and the hanging swamps of the Blue Mountains provide habitat for a range of fauna including birds, reptiles and frogs. Reliance of fauna on the swamps increases during low rainfall periods. A range of threatened fauna including the Blue Mountains Water Skink, Eulamprus leuraensis, the Giant Dragonfly, Petalura gigantea, the Giant Burrowing Frog, Heleioporus australiacus, the Red-crowned Toadlet, Pseudophryne australis, the Stuttering Frog Mixophyes balbus and Littlejohn’s Tree Frog, Litoria littlejohni, are known to use the swamps as habitat. Of these species, the frogs are likely to suffer the greatest impacts as a result of hydrological change in the swamps because of their reliance on the water within these areas either as foraging or breeding habitat. Plant species such as Persoonia acerosa, Pultenaea glabra, P. aristata and Acacia baueri ssp. aspera are often recorded in close proximity to the swamps.

Cliffline species such as Epacris hamiltonii and Apatophyllum constablei that rely on surface or subsurface water may also be affected by hydrological impacts on upland swamps, as well as accelerated cliff collapse associated with longwall mining.

15. Flora and fauna may also be affected by activities associated with longwall mining in addition to the direct impacts of subsidence. These activities include clearing of native vegetation and removal of bush rock for surface facilities such as roads and coal wash emplacement and discharge of mine water into swamps and streams. Weed invasion, erosion and siltation may occur following vegetation clearing or enrichment by mine water. Clearing of native vegetation, Bushrock removal, Invasion of native plant communities by exotic perennial grasses and Alteration to the natural flow regimes of rivers and streams and their floodplains and wetlands are listed as Key Threatening Processes under the Threatened Species Conservation Act (1995).

.

The following threatened species and ecological communities are known to occur in areas affected by subsidence due to longwall mining and their habitats are likely to be altered by subsidence and mining-associated activities:

Endangered Species

- Epacris hamiltonii a shrub

- Eulamprus leuraensis Blue Mountains Water Skink

- Hoplocephalus bungaroides Broad-headed Snake

- Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot

- Petalura gigantea Giant Dragonfly

.

Vulnerable species

- Acacia baueri subsp. aspera

- Apatophyllum constablei

- Boronia deanei

- Cercartetus nanus Eastern Pygmy Possum

- Epacris purpurascens var. purpurascens

- Grevillea longifolia

- Heleioporus australiacus Giant Burrowing Frog

- Ixobrychus flavicollis Black Bittern

- Leucopogon exolasius

- Litoria littlejohni Littlejohn’s Tree Frog

- Melaleuca deanei

- Mixophyes balbus Stuttering Frog

- Myotis adversus Large-footed Myotis

- Persoonia acerosa

- Potorous tridactylus Long-nosed Potoroo

- Pseudophryne australis Red-crowned Toadlet

- Pteropus poliocephalus Grey-headed Flying Fox

- Pterostylis pulchella

- Pultenaea aristata

- Pultenaea glabra

- Tetratheca juncea

- Varanus rosenbergi Rosenberg’s Goanna

.

Endangered Ecological Communities

.

- Genowlan Point Allocasuarina nana Heathland

- Newnes Plateau Shrub Swamp in the Sydney Basin Bioregion

- O’Hares Creek Shale Forest

- Shale/Sandstone Transition Forest

.

Species and populations of species not currently listed as threatened but that may become so as a result of habitat alteration following subsidence due to longwall mining include:

- Acacia ptychoclada

- Almaleea incurvata

- Darwinia grandiflora

- Dillwynia stipulifera

- Epacris coricea

- Grevillea acanthifolia subsp. acanthifolia

- Hydromys chrysogaster Water rat

- Lomandra fluviatilis

- Olearia quercifolia

- Pseudanthus pimelioides

.

16. Mitigation measures to repair cracking creek beds have had only limited success and are still considered experimental (ACARP 2002). Cracks less than 10 mm wide may eventually reseal without active intervention provided there is a clay fraction in the soil and at least some water flow is maintained.

Cracks 10-50 mm wide may be sealed with a grouting compound or bentonite.

Cracks wider than 50 mm require concrete (ACARP 2002). Pattern grouting in the vicinity of Marhnyes Hole in the Georges River has been successful at restoring surface flows and reducing pool drainage following fracturing of the riverbed (International Environmental Consultants 2004). Grouting of cracks also appears to have been relatively effective in Wambo Creek in the Hunter Valley. Installation of a grout curtain in the Cataract River, however, has been only partially successful and it was concluded in 2002, after rehabilitation measures had taken place, that the environment flows released from Broughtons Pass Weir by the Sydney Catchment Authority were insufficient to keep the Cataract River flowing or to maintain acceptable water quality (DIPNR 2003). Mitigation measures themselves may have additional environmental impacts due to disturbance from access tracks, the siting of drilling rigs, removal of riparian vegetation, and unintended release of the grouting material into the water. Furthermore, even measures that are successful in terms of restoring flows involve temporary rerouting of surface flows while mitigation is carried out (generally for 2-3 weeks at each grouting site). Planning for remediation measures may also be hampered by the lack of predictability of some impacts, and difficulties gaining access to remote areas where remedial works are needed. The long-term success of mitigation measures such as grouting is not yet known. It is possible that any ongoing subsidence after grouting may reopen cracks or create new ones.

Further, it is not yet known whether the clay substance bentonite, which is often added to the cement in the grouting mix, is sufficiently stable to prevent shrinkage. Grouting under upland and hanging swamps that have no definite channel is probably not feasible.

17. Empirical methods have been developed from large data sets to predict conventional subsidence effects (ACARP 2001, 2002, 2003). In general, these models have proved more accurate when predicting the potential degree of subsidence in flat or gently undulating terrain than in steep topography (ACARP 2003). A major issue identified in the ACARP (2001, 2002) reports was the lack of knowledge about horizontal stresses in geological strata, particularly those associated with river valleys. These horizontal stresses appear to play a major role in the magnitude and extent of surface subsidence impacts. The cumulative impacts of multiple panels also appear to have been poorly monitored. The general trend in the mining industry in recent years toward increased panel widths (from 200 up to 300 m), which allows greater economies in the overall costs of extraction, means that future impacts will tend to be greater than those in the past (ACARP 2001, 2002).

18. In view of the above the Scientific Committee is of the opinion that Alteration of habitat following subsidence due to longwall mining adversely affects two or more threatened species, populations or ecological communities, or could cause species, populations or ecological communities that are not threatened to become threatened.

.

References

.

ACARP (2001) ‘Impacts of Mine Subsidence on the Strata & Hydrology of River Valleys – Management Guidelines for Undermining Cliffs, Gorges and River Systems’. Australian Coal Association Research Program Final Report C8005 Stage 1, March 2001.

ACARP (2002) ‘Impacts of Mine Subsidence on the Strata & Hydrology of River Valleys – Management Guidelines for Undermining Cliffs, Gorges and River Systems’. Australian Coal Association Research Program Final Report C9067 Stage 2, June 2002.

ACARP (2003) ‘Review of Industry Subsidence Data in Relation to the Influence of Overburden Lithology on Subsidence and an Initial Assessment of a Sub-Surface Fracturing Model for Groundwater Analysis’. Australian Coal Association Research Program Final Report C10023, September 2003.

AWT (2000) ‘Investigation of the impact of bed cracking on water quality in the Cataract River.’ Prepared for the Dept. of Land and Water Conservation Sydney South Coast Region. AWT Report no. 2000/0366.

Bell FG, Stacey TR, Genske DD (2000) Mining subsidence and its effect on the environment: some differing examples. Environmental Geology 40, 135-152.

Benson DH, Keith DA (1990) The natural vegetation of the Wallerawang 1:100,000 map sheet. Cunninghamia 2, 305-335.

Booth CJ, Bertsch LP (1999) Groundwater geochemistry in shallow aquifers above longwall mines in Illinois, USA. Hydrogeology Journal 7, 561-575.

Booth CJ, Spande ED, Pattee CT, Miller JD, Bertsch LP (1998) Positive and negative impacts of longwall mine subsidence on a sandstone aquifer.

Environmental Geology 34, 223-233.

DIPNR (2003) ‘Hydrological and water quality assessment of the Cataract River; June 1999 to October 2002: Implications for the management of longwall coal mining.’ NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Environment, Wollongong.

DLWC (2001) ‘Submission to the Commission of Inquiry into the Proposed Dendrobium Underground Coal Mine Project by BHP Steel (AIS) Pty Ltd, Wollongong, Wingecarribee & Wollondilly Local Government Areas’. Department of Land and Water Conservation, July 2001.

Elsworth D, Liu J (1995) Topographic influence of longwall mining on ground-water supplies. Ground Water 33, 786-793.

Everett M, Ross T, Hunt G (eds) (1998) ‘Final Report of the Cataract River Taskforce. A report to the Upper Nepean Catchment Management Committee of the studies of water loss in the lower Cataract River during the period 1993 to 1997.’ Cataract River Taskforce, Picton.

Gibbins L (2003) A geophysical investigation of two upland swamps, Woronora Plateau, NSW, Australia. Honours Thesis, Macquarie University.

Gill DR (2000) Hydrogeologic analysis of streamflow in relation to undergraound mining in northern West Virginia. MSc thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Holla L (1997) Ground movement due to longwall mining in high relief areas in New South Wales, Australia. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences 34, 775-787.

Holla L, Barclay E (2000) ‘Mine subsidence in the Southern Coalfield, NSW, Australia’. Mineral Resources of NSW, Sydney.

International Environmental Consultants Pty Ltd (2004) ‘Pattern grouting remediation activities: Review of Environmental Effects Georges River Pools 5-22. May, 2004’.

Jones DC, Clark NR (eds) (1991) Geology of the Penrith 1:100,000 Sheet 9030, NSW. Geological Survey, NSW Department of Minerals and Energy.

Karaman A, Carpenter PJ, Booth CJ (2001) Type-curve analysis of water-level changes induced by a longwall mine. Environmental Geology 40, 897-901.

Keith DA (1991) Coexistence and species diversity in upland swamp vegetation. PhD thesis. University of Sydney.

Keith DA (1994) Floristics, structure and diversity of natural vegetation in the O’Hares Creek catchment, south of Sydney. Cunninghamia 3, 543-594.

Keith DA, Benson DH (1988) The natural vegetation of the Katoomba 1:100,000 map sheet. Cunninghamia 2, 107-143.

Kodela PG, Sainty GR, Bravo FJ, James TA (2001) ‘Wingecarribee Swamp flora survey and related management issues.’ Sydney Catchment Authority, New South Wales.

Keith DA, Myerscough PJ (1983) Floristics and soil relations of upland swamp vegetation near Sydney. Australian Journal of Ecology 18, 325-344.

NPWS (2001) ‘NPWS Primary Submission to the Commission of Inquiry into the Dendrobium Coal Project’. National Parks and Wildlife Service, July 2001.

Sidle RC, Kamil I, Sharma A, Yamashita S (2000) Stream response to subsidence from underground coal mining in central Utah. Environmental Geology 39, 279-291.

Stout BM III (2003) ‘Impact of longwall mining on headwater streams in northern West Virginia’. Final Report, June 2003 for the West Virginia Water Research Institute.

Stout BM III (2004) ‘Do headwater streams recover from longwall mining impacts in northern West Virginia’. Final Report, August 2004 for the West Virginia Water Research Institute.

Young ARM (1982) Upland swamps (dells) on the Woronora Plateau, N.S.W. PhD thesis, University of Wollongong.

Young ARM (1986) The geomorphic development of upland dells (upland swamps) on the Woronora Plateau, NSW, Australia. Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie N.F. Bd 30, Heft 3,312-327.

Young RW, Wray RAL (2000) The geomorphology of sandstones in the Sydney Region. In McNally GH and Franklin BJ eds Sandstone City – Sydney’s Dimension Stone and other Sandstone Geomaterials. Proceedings of a symposium held on 7th July 2000, 15th Australian Geological Convention, University of

Technology Sydney. Monograph No. 5, Geological Society of Australia, Springwood, NSW. Pp 55-73.

Young RW, Young ARM (1988) ‘Altogether barren, peculiarly romantic’: the sandstone lands around Sydney. Australian Geographer 19, 9-25.