by Editor 20100810.

The following article appeared on ABC Television in Tasmania (Australia), Friday 16th July 2010.

‘Scientists are concerned about a decline in eastern quoll numbers in Tasmania.

The eastern quoll is a carnivorous marsupial and is sometimes known as a native cat.

Scientists predicted quoll numbers would rise as the tasmanian devil population was decimated by the facial tumour disease.

But spotlighting survey work has shown numbers have fallen by half.

University of Tasmania honours student, Bronwyn Fancourt, is now doing more detailed survey work but says initial results are concerning.

“We really need to protect these guys because we don’t want to see them end up as another thylacine,” she said.

Blood samples and measurements will be taken for further research into why the species is in decline.’

Further reading on the plight of Quolls in Tasmania:

[The following article was extracted from the Tasmanian Times of 15th May 2010, by Nick Mooney, Richmond (Tasmania), ^http://www.tasmaniantimes.com/index.php/article/cynical-dismissal-of-substantial-material-evidence ].

‘Cynical dismissal of substantial material evidence‘

‘An acceptance of unreferenced anecdotes as proof (of eastern quolls being introduced to Bruny in the 1970s) alongside cynical dismissal of substantial material evidence that has passed several reviews (of foxes in Tasmania) sits very poorly with your call to just deal with facts Mr Clarke (letters, Mercury 15th).

I presume your anecdotal proof is nobody you know remembering eastern quolls to be on Bruny before 1970.

Maybe they were rare then and simply overlooked or just never officially recorded just like much wildlife there.

DNA comparisons suggests Bruny Island quolls have been separated from mainland Tasmanian populations for a lot longer than 40 years.

I remain to be convinced eastern quolls were introduced to Bruny in the 1970s. Radical boom-bust cycles are a natural feature of eastern quoll ecology and the current boom will bust.

There are no species on Bruny that do not cope with eastern quolls and or spotted-tailed quolls and devils elsewhere in Tasmania so who’s mounting the scare campaign Mr Clarke?

Eastern quolls are not top predators on Bruny. Masked owls prey on them as can cats and diurnal birds of prey are one reason they are nocturnal. Eastern quolls are extinct on mainland Australia mainly because of foxes and will be amongst the first to go if foxes get fully established here.

If you look beyond your backyard Mr Clarke you might find you actually have an asset.

Finally, I have never been head of wildlife management and my views sometimes conflict with those of the department.

I prefer to put devils on Bruny because its a restoration and not a range extension such as Maria Island, the department’s preference, and something being assessed for years before the Tasmanian Conservation Trust showed interest.’

‘Survival fears for quolls‘

[This article was extracted from the Hobart Mercury of 16-July 2010, by Charkes Waterhouse, http://www.themercury.com.au/article/2010/07/16/159131_tasmania-news.html ].

‘Another native Tasmanian species is under threat, with the population of eastern quolls falling around the state.

The decline has alarmed experts as the eastern quoll was expected to thrive to fill the void left by falling numbers of disease-ravaged Tasmanian devils.

The University of Tasmania and the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment will investigate the extent of the falling population.

DPIPWE threatened species zoologist Clare Hawkins said the study would provide scientific data on the status of the species.

She said annual spotlighting information suggested the population of the eastern quoll had declined.

“It does appear quite complicated as at the same time there are areas of the state, such as Bruny Island, where landowners are reporting they have never seen so many eastern quolls,” she said.

“It may be that in some areas of the state they remain in high numbers, whereas other parts of Tasmania have had declines, or it may be that in some areas they are coming into closer contact with the urban environment making them more observed, which could be masking an overall decline.”

University of Tasmania zoology honours student Bronwyn Fancourt said a systematic survey would provide scientific information on the wild population, building on information about population changes and showing whether there were areas where increases or decreases had occurred.

“Tasmania is the last stronghold for the eastern quoll as it is now presumed extinct on mainland Australia, which highlights the importance of having scientific data on what the population is doing,” Ms Fancourt said.

She said the survey was taking place through a trap-and-release program at various sites.

Information from this program and any other data collected could help an understanding of possible contributory factors if the quolls were in decline.

‘Foxes, quolls, devils and 1080‘

[This article is extracted from the Tasmanian Times, 24-Nov-2006, by wildlife biologist Nick Mooney,^ http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php?/article/nick2/].

Assessing the Risks

When assessing the risks of 1080 fox baiting to individuals or populations of any particular species a number of things should be taken into account, including:

• The physiological sensitivity of the species to 1080 poison (depends on many things principal amongst them the historic exposure of the species to 1080 as it occurs in Australian plants), something that can be experimentally measured.

• How many baits the species might find (depends on the sensory abilities of the animal, how, where and the number of baits placed in a given area — the landscape density).

• How many baits the species might eat within a certain period. To cause death, a lethal dose has to be ingested in a certain time — usually within 2 days because sub lethal doses of 1080 are metabolised. Dried meat baits are too hard for many species to do more than mouth and nibble but many species can eat other baits such as Foxoff (eg non toxic bait trials — Belcher 1998 and DPIW data). There is evidence some species can detect 1080 in baits and avoid eating them (eg the spotted-tailed quoll in Foxoff baits, Kortner et al 2003).

• How much 1080 is left in baits when they are eaten (if they are decomposing, 1080 will have also degraded to a comparable degree).

• The likelihood of the species digesting baits (many carnivores and omnivores regurgitate food containing significant amounts of 1080. There are past records of devils regurgitating 1080-laced food in captive trials).

• The age and health of the individual eating the bait or carcasses of poisoned animals (smaller individuals of a species likely have higher metabolisms and consequent usual higher sensitivity to 1080 and healthy individuals likely have more resistance to 1080)

• The size of individuals in the population at baiting (size effects metabolism and consequent susceptibility to 1080. Individuals of the same species might be different in size in different populations, eg devils on the east coast of Tasmania are much larger than west coast individuals, and there may be many small juveniles just after breeding).

• How the species’ range and abundance overlaps with 1080 baiting (the proportion of the species that might be exposed to baiting).

Physiological sensitivity

The level of physiological sensitivity of a species to 1080 is usually described as the species’ LD50 – that is the mg of 1080 ingested per kg of animal during a very short period that will kill 50% of the individuals exposed (LD = Lethal Dose). Most of the research on LD50s for Australian animals and the potential impacts of 1080 was done on captive animals decades ago by Dr John McIlroy, then at CSIRO, and published in various issues of Australian Wildlife Research (eg McIlroy, 1981a, 1981b and 1981c) and he still gives occasional advice on the matter to DPIW. It is doubtful if this work could ever be substantially expanded or repeated because it involves lethal testing.

LD50s for some Tasmanian animals of obvious interest as potential non-target consumers of fox baits (mainly dried kangaroo meat but also some Foxoff meat compound) are

We see that kg-for-kg, red foxes are over 13 times as sensitive to 1080 as are spotted-tailed quolls and 30 times as sensitive as devils. The LD50 for spotted-tailed quolls is lower than might be expected considering those for its relatives, the eastern quoll and Tasmanian devil. McIlroy has expressed the opinion the small sample size and temperatures the results were obtained under may have given a too low result. This is born up by most mainland research that shows little effect of fox and wild dog baiting on spotted-tailed quolls (eg Kortner et al 2003).

Persistence of 1080 in baits

In the field, 1080 breaks down by microbe and fungal activity. Meat baits as used in Tasmania are about 120g of fresh kangaroo meat, each dosed with 3mg of 1080 dried hard to about 40g for storage then use (eg Saunders et al 1995). By the time they are set (buried) some 1080 is already broken down and on average they then only contain 2.7mg – a 10% loss. Once buried, degradation of 1080 accelerates, the rate depending on soil conditions (particularly moisture and temperature) and consequent baits degradation. Such degradation of 1080 is well known (eg Saunders et al 2000).

Tasmanian 1080 fox dried meat baits have been tested after different times in the ground in field conditions and on average after 2 days in the ground only 43.3% of 1080 remained, after 5 days there was 28.2% left, after 10 days 19.7% and after 15 days 11.6%. However, there was considerable variation even between neighbouring baits; some in wet places have much less 1080 residue and some in dry places much more than the average.

Number of baits needed to put individuals at risk

Considering the sensitivity of spotted-tailed quolls, devils and foxes to 1080 and degradation of 1080 in buried baits we can calculate how many baits buried for various times need to be eaten by different sized spotted-tailed quolls, devils and foxes within 2 days to have a 50% chance of being killed.

We see below that a very small spotted-tailed quoll will consume an LD50 if it eats most of one freshly layed bait but that same animal would have to eat at least 5 baits within 2 days once they had been in the ground for two weeks to be at similar risk. Similarly a very large spotted-tailed quoll would have to eat more than 4 freshly layed baits to be at risk but more than 30 after two weeks in the ground.

We see below that even a very small devil (probably not even weaned) needs to eat more than 3 freshly layed baits within 2 days to reach an LD50 and large devils need to eat very many baits in a short period to reach an LD50.

We see that foxes are extremely susceptible to 1080 baiting and in many circumstances need less than 1 bait to reach an LD50.

The chances of individuals finding enough baits in a short enough period to be at risk

Extensive testing with foxes on mainland Australia clearly shows they can find baits immediately they are buried; initial take is often high and usually continues until baits and/or foxes are greatly reduced (eg Saunders et al 1995). Limited testing with Foxoff and fresh meat baits with captive and wild spotted-tailed quolls in NSW showed they could detect buried baits but trials only identified this species as taking 2 of 7 baits taken after 3-4 weeks buried adjacent to a spotted-tailed latrine in the wild (Belcher 1998); results consistent with Tasmanian observations considering time buried and that baits were replaced exactly where taken (see below).

Research on take of fox baits without 1080 was undertaken with an isolated, island population of devils (no quolls or foxes present). Initial take was very low (a few % per night) but escalated once baits began to rot, to the point where most baits were taken after 3 weeks. These results were mirrored in places with devils and spotted-tailed quolls, devils and eastern quolls and eastern quolls alone; there are no places exclusively with spotted-tailed quolls in Tasmania. If baits were replaced in a hole where a previous bait had rotted then re-take could be immediate but if placed in a new hole take was very low. Devils in particular would sometimes deeply excavate holes in which baits had rotted.

It seems devils and quolls are not well equipped to find buried baits until they rot or are otherwise smelly (or replaced); probably there has been no need in their evolution. On the other hand, foxes and dogs evolved under conditions of extremely harsh winters where caching and recovering food (or raiding others’ caches) was fundamental to survival. Therefore, these canids are ‘professionals’ at finding buried food (eg Saunders et al 1995, Twigg et al 2000). This does not mean that other species cannot find any buried baits or might even be exposed accidentally (eg during echidna excavations) but it is a clear trend.

There has been considerable questioning of what animals have taken the thousands of baits of the nearly 80,000 sofar set in Tasmania. Checking baits daily allows a reasonable judgment of what might have taken them and in the early days of baiting (2002/3) when daily checks were undertaken about 20 baits were recorded as taken in typical fox style (as seen else where in Australia). Once baiting expanded and baits were only checked at recovery such judgments of take could rarely be made; hence the experiments reported here. If baits were recovered 2-3 weeks after burial few were missing but if it was 3 weeks or more most might be – it seemed a simple fact of rotting and then being found.

In operational fox baiting in Tasmania, baits are buried at a landscape density of 5-10/km2. The number of baits in an animal’s home range can also be considered and how much competition there might be for baits. A large devil might have 100 baits in its home range but that home range would likely be shared by 10-30 other devils plus quolls (and possibly foxes). Thus, the baits available per individual are comparatively few.

The chances of individuals eating enough baits in a short enough period to be at risk

Although they can easily eat soft baits, test have shown that small or even medium sized spotted-tailed quolls and very small devils do not (probably can not) eat very dry and hard baits and it is not until they are independent that they are likely to be under enough nutritional pressure and are strong enough to eat such. Tests on captive mainland Australian spotted-tailed quolls support these results (Belcher 2000).

What actually happens in the field?

Considerable research has been done on effects of 1080 fox baiting on spotted-tailed quolls on mainland Australia (eg Kortner ET al 2003). In Tasmania, experimental 1080 baiting was not carried out but rather, research waited until an operational baiting occurred in an area with enough spotted-tailed quolls to usefully study (near Wynyard).

Although there were too few quolls in the study sites area (and a comparative control site with no baiting) to have statistically robust comparisons of numbers before and after baiting we found individual spotted-tailed quolls similarly persisted in both areas through and after baiting. Importantly, there were breeding females (with pouch young) and free ranging juveniles present in both sites after baiting; there was no identifiable difference between baited and non-baited sites. This work will be repeated as opportunity presents.

In the northern midlands where the effects of 1080 fox baiting on devils was being studied, there was also a ‘background’ population of spotted-tailed quolls. Trapping after a prolonged baiting period showed all elements of a normal devil population in place – breeders and juveniles with no apparent drop in density. Perhaps most interestingly, in the months after this research a substantial drop in numbers of devils due to Devil Facial Tumour Disease occurred and in another 6 months numbers of spotted-tailed quoll seemed to have measurably increased (probably due to decreased competition and predation from the fewer devils) and has stayed high with an apparently normal mix of breeders and juveniles. DFTD it seems has absolutely overwhelming effects (even if indirect) compared to fox baiting.

In an area in which Foxoff meat compound baits were operationally used extensive capture-mark-recapture studies were done of large local populations of Tasmanian bettongs Bettongia giamardi and brushtail possums Truchosaurus vulpecula, two species likely to eat these baits. Very few Foxoff baits were taken and there was no difference in population change between the baited site and a control site.

These Tasmanian ‘pilot’ studies suggest there is little if any damage to local populations of spotted-tailed quoll, Tasmanian devils, Tasmanian bettongs or brushtail possum from 1080 fox baiting in Tasmania as is known to have severe effects on fox populations on mainland Australia (eg Saunders et al 1995).

State-wide Effects

A final check can be made by looking at what proportion of Tasmania’s spotted-tailed quoll and devil population might be exposed to 1080 fox baiting. Sofar, 1080 fox baiting has only touched the fringe of Tasmania’s core spotted-tailed quoll habitat and perhaps less than 2-3% of Tasmania’s spotted-tailed quolls have been in baited areas. Similarly perhaps 5% of Tasmania’s devils have been in baited areas. These areas and percentages may increase by half with planned fox baiting but, even then the reality is little or no effect on a small proportion of the State’s populations of these important species.

References

- Belcher, C. (1998). Susceptibility of the tiger quoll, Dasyurus maculatus, and the eastern quoll D. viverrinus, to 1080-poisoned baits in control programmes for vertebrate pests in eastern Australia. Wildlife Research 25, 33-40.

- Belcher, C. (2000). The ecology of the Tiger Quoll Dasyurus maculatus, in south-eastern Australia. Unpublished PhD thesis, Deakin Uni.

- Kortner, G., Gresser, S. and B. Harden (2003). Does fox baiting threaten the spotted-tailed quoll, Dasyurus maculatus? Wildlife Research 30, 111-118.

- McIlroy, J. C. (1981a). The sensitivity of Australian mammals to 1080 poison. 1. Intraspecific variation and factors effecting acute toxicity. Australian Wildlife Research 8, 369-383.

- McIlroy, J. C. (1981b). The sensitivity of Australian mammals to 1080 poison. 11. Marsupial and eutherian carnivores. Australian Wildlife Research 8, 385-399.

- McIlroy, J.C. (1981). The sensitivity of Australian animals to 1080 poison.1X. Comparisons between the major groups of animals, and the potential danger non-target species face from 1080 poisoning campaigns. Australian wildlife Research 13, 39-48.

- Saunders, G., McLeod, S. and B. Kay (2000). Degradation of sodium monoflouroacetate (1080) in buried fox baits. Wildlife Research 27, 129-135.

- Twigg, L., Eldridge, S., Edwards, G., Shakeshaft, B., dePeru, N. and N. Adams (2000). The longevity and efficacy of 1080 meat baits used for dingo control in central Australia). Wildlife Research 27, 473-481.

Other Useful Reading

Kinnear, J.E. (2003). Eradicating the fox in Tasmania: A review of the Fox Free Tasmania Program. Unpublished report to DPIWE, Hobart.

Saunders, G., Coman, B., Kinnear, J. and M. Braysher (1995). Managing vertebrate pests: Foxes. Australian Government Printing Service, Canberra

Saunders, G., Lane, C., Harris, S. and C. Dickman (2006). Foxes in Tasmania: A Report on the Incursion of an Invasive Species. IACRC, Canberra.

Nick Mooney is a wildlife biologist with DPIW and has been working with Tasmanian wildlife for more than 30 years. Amongst other hats, he pioneered Tasmanian rehabilitation and conservation of raptors including eagles in forestry, has monitored reports of Thylacines and foxes, helped with responses to newly discovered diseases, whale strandings and oil spills and developed practical conservation of devils and innovative wildlife tourism. Most recently he kicked off the response to Devil facial Tumour Disease and has been giving advice for the response to recent evidence of foxes in Tasmania. Nick is assessing the potential ecological effects of DFTD, foxes and cats; he sees the biggest ecological threat as establishment of foxes because of DFTD, a process that could cause the ultimate long term threat to devils (his favourite animal).

Nick Mooney

There has been a recent spate of public concern over the effect that 1080 baiting targeting the red fox Vulpes vulpes in Tasmania might have on the spotted-tailed quoll Dasyurus maculatus and the Tasmanian devil Sarcophilus harrisii.

Considerable research has been done on that quoll species on mainland Australia, studies augmented by work in Tasmania on both it and devils.

‘Foxes, quolls, devils and 1080 #2‘

[This article is extracted from the Tasmanian Times, 27-Nov-2006, by David Obendorf,^ http://tasmaniantimes.com/index.php?/article/obis1/].

AS NICK MOONEY states: ‘Most of the research on lethal dose to 50% (LD50) for Australian animals and the potential impacts of 1080 was done on captive animals decades ago by John McIlroy, then at CSIRO, and published in various issues of Australian Wildlife Research. It is doubtful if this work could ever be substantially expanded or repeated because it involves lethal testing.’ (Foxes, quolls, devils and 1080)

With DPIW poised to embark on a decade-long $56 million dollar fox eradication campaign using 1080 meat baits as the principle eradication tool, I believe there are several very good reasons why 1080 testing of non-target Tasmanian species exposed to these baits must now be repeated. For Tasmanian wildlife authorities to rely solely on this unrepeated toxicological data would be reckless.

John McIlroy commenced his work on the sensitivity of Australian animals to the poison 1080 (Sodium Fluoroacetate) a quarter of a century ago. John was a research scientist working at the CSIRO Division of Wildlife Research at Gunghalin near Canberra. During the period from 1980-86 he conducted a series of dose-response experiments to assess the sensitivity of 1080 on a representative range of Australian animals, covering species in all the main vertebrate taxa. He published 9 scientific papers in this series; 7 as the sole author and 2 in collaboration with others.

In documenting his research findings, John was careful to firstly prepare the theoretical and statistical ground work on which this series of experimentally-based toxicity would be based (McIlroy 1981a).

“In toxicological work the sensitivity of different [species of] animals to a poison is usually expressed as the LD50 or median lethal dose, a statistical estimate of the dose — in milligrams of poison per kilogram body weight, that will kill 50% of a large population.

The LD50 of a poison and its 95% confidence limits are only an indication of the values that might be expected from repeated trials on the same strain of animals under the same experimental conditions.”

In applying the LD50 values to a test poison, McIlroy states:

“The necessity for such a standardised procedure has been questioned … [as] statistically significant differences in LD50 values (up to 3.2 fold) within and between laboratories, related to differences in experimental procedure, … [but] these were not great enough to change the interpretation of the relative hazards of the test chemical involved. However, because I was concerned with a controversial poison [1080] and its toxicity to a variety of wild animals, I felt it was important to assess the effects that differences in experimental procedure might have on LD50 values of 1080 and, if necessary, design a procedure to minimize such sources of variation.” (McIlroy 1981a)

In his second paper detailing the results of his experimental studies on marsupials and placental mammals, John began on a cautionary note:

“The effect that these [1080] poisoning campaigns are having on non-target or native animal populations is not known, despite occasional reports of individuals of these species being found dead or ‘vanishing’ from areas in which 1080 has been used.” (McIlroy 1981b).

Targeting dingoes

McIlroy was very considered in any reliance of these experimentally derived LD50 values:

“In reality many factors are involved in determining whether an individual or what proportion of a population may be killed by a [1080] poisoning campaign. The preceding theoretical analysis involved mean body weights of only small samples of animals, LD50s obtained under specific experimental conditions, and a particular concentration of 1080 in each bait plus the assumptions about bait intake by free-living species. All are likely to vary in different field situations, altering the risk each individual carnivore faces.”

Based on 1080 baiting campaigns targeting dingoes (& wild dogs), John McIlroy made some thoughtful recommendations when deciding on the most effective bait size and quantity of 1080 per bait for maximal kill of target species and minimal impact to non-target (native) species.

“The data on [1080] sensitivities do provide fundamental information for the planning of dingo-poisoning operations. For example, if the aim is to obtain maximal control with minimum dose it would be best to plan the baiting on the basis of a LD100 based on twice the upper confidence limit of the LD50 and the weight of the heaviest specimen reported. In contrast, to assess the hazard to a non-target species, calculations might be best based on the lower confidence limit of the LD50, or some other lower figure, and either the mean weight or much lower body weights of, for instance, immature animals.”

McIlroy went on to do a theoretical calculation to show this point for dingoes (the target carnivore) and spotted-tail quolls (a non-target carnivore).

“The heaviest individual [dingo] caught in the Eastern Highlands was 25 kg. Thus if the LD100 is assumed to be approximately twice the upper confidence limit of the LD50 (i.e. 0.3mg/kg BW), it would be necessary to get 7.5 mg of 1080 into a dog of this size to kill it. Similar calculations for tiger cats [spotted-tail quolls], using twice the lower confidence limit of the LD50 (i.e. 2.56 mg/kg BW) and taking the mean body weight of 2.8 kg, indicate that 7.17 mg of 1080 is a lethal dose for [this species].

Applying McIlroy’s precautionary recommendation to the mean body weight for immature spotted-tail quolls of 1.1 kg, only 2.8 mg of 1080 is a lethal dose.

Obtain a lethal dose

The same theoretical calculation and logic can be applied can be applied to 1080 poisoning campaigns targeting foxes.

For an extreme body weight fox of 6 kg and applying an LD100 that is approximately twice the upper confidence limit of the LD50 (i.e. 0.26mg/kg BW), it would be necessary to get a fox to consume 1.56 mg of 1080 to kill it (not 3 mg of 1080 per bait). If each dried kangaroo meat (DKM) baits contained this amount of 1080, one bait would kill all foxes less than 6 kg. When applying McIlroy’s precautionary calculation to a mean body weight for immature quolls, such animals would need to ingest at least two baits to obtain a lethal dose.

“From the viewpoint of trying to safeguard tiger cats [spotted-tail quolls]; therefore, it is obviously necessary to keep 1080 concentration in baits as low as possible.” (McIlroy 1981b)

One variable that McIlroy particularly commented on was the effect of ambient temperature on the sensitivity of 1080 poison. He was concerned that his experimental trials to set the LD50 for many native marsupials were carried out at about 22°C (in controlled environment rooms). He noted that in relation toxicity studies on the spotted-tail quolls, trials were conducted at 13°C where the LD50 was calculated at 1.85 mg/kg BW.

“… different ambient temperatures cause two to five fold differences in the susceptibility of mice and guinea pigs to 1080. Both species are susceptible at both low and high ambient temperatures than they are at medium temperatures. If similar responses occur amongst other, larger homeotherms, this might explain the relatively low LD50 for the tiger cat [spotted-tail quoll] compared to those for the other native cats [quolls]. The possibility exists, therefore, that if these trials had been carried out at 22°C [instead of 13°C], the LD50 would have been slightly higher than 1.85 mg/kg BW.

Ambient temperatures obviously vary considerably between field poisoning situations, both geographically and diurnally, so a LD50 obtained at 22°C, or a dose that will kill 50% of a population experiencing this ambient temperature, must be regarded as only a general value. Greater population mortality may be expected at much lower or higher environmental temperatures.” (McIlroy 1981b)

In relation to the most susceptible non-target marsupial carnivore, the spotted-tail quoll, 1080 baiting programs targeting foxes and wild dogs are still reliant on McIlroy’s highly qualified toxicology studies and LD50 calculations.

In obtaining his LD50 levels for each species, McIlroy orally dosed between 3 and 5 individuals at dose intervals of 1.26 in 4 distinct dose groupings. For spotted-tailed quoll he used 12 animals. The LD50 was calculated at 1.85 mg/kgm with 95% confidence intervals of 1.28 to 2.68 mg/kgm BW.

Other animals begin to vomit

Clinical observations were made on the experimentally poisoned animals.

“Most commonly, affected animals suddenly became hyper-excited, with rapid breathing, bouts of trembling and sometimes periodic circling within their cages. Again, some animals may then recover while other begin to vomit, convulse, or both. With some animals, particularly the eastern native and tiger cats [quolls] and Tasmanian devils, the first symptom is the sudden onset of vomiting.

Convulsions were triggered by disturbance, such as the opening of a door, sudden movement by an observer, or convulsion by a neighbouring animal. In rough order, these symptoms include: restlessness; increased hyperexcitability or response to stimuli; bouts of trembling; rapid, shallow breathing; incontinence[involuntary passing of urine and/or faeces] or diarrhoea; excessive salivation; twitching of the facial muscles; nystagmus (involuntary eyeball movement exposing the whites of the eyes)or bulging eyes with large (dilated) pupils and rapid blinking plus, in domestic cats, discharge of mucus from the eyes); slight lack of coordination or balance; abrupt bouts of vocalisation; and finally, sudden burst of violent activity such as racing around the cage, or biting the cage mesh or other objects. All affected animals then fall to the ground in a tetanic seizure, with hind limbs or all four limbs and sometimes the tail extended rigidly from their arched bodies. At other times the front feet are clasped together, clenched or used to scratch frantically at the cage walls. This tonic phase is then followed by a clonic phase in which the animals lie and kick and ‘paddle’ with the front legs and sometimes squeal, crawl around or bite at objects. During this phase the tongue and penis may be extruded, the eyes rolled back so that only the whites show and the teeth are ground together. Breathing is rapid but laboured, with some animals partly choking on their saliva. Finally such animals begin to relax, breathing more slowly and shallowly and lying quietly with the hind legs still extended but apparently semiparalysed (paresis).

From then on individual animals either: (1) gradually recover; (2) die shortly afterwards; (3) after a short or long delay (e.g. 5 min or 3-4 h) experience another one or two series of convulsions and then die shortly afterwards or eventually recover; (4) remain lying quietly, scarcely breathing or moving, until death up to 6 days later.

It is noteworthy that in McIlroy’s observations on carnivorous marsupials exposed to sub-lethal doses of 1080, he noted that animals that did not die but ‘remained weak for 2 or more days’. From this we can infer that the sub-lethal consequences of 1080 poisoning may therefore affect an animal’s ability to evade predation by other animals and affect their ability to find safe refuge.

McIlroy also makes the following observations:

“The pouch young of tammar wallabies are significantly more susceptible to 1080 than adults (P>0.01. The pouch young of brush-tailed possums and northern native cats, Dasyurus hallicatus, similarly appear to be more sensitive than adults. More pouch young pouch young possums than adults died at each dose level, although only their mothers were dosed with 1080; presumably the young ingested lethal amounts of 1080 in the milk. The eight pouch young of one northern native cat also died within 24 h after their mother received a non-lethal dose (84% of a LD50 )but the five pouch young of a tiger cat, Dasyurus maculatus, survived in similar circumstances (74% of a LD50 ). [There are] similar reports of young rats killed by milk from their poisoned mothers.” (McIlroy 1981).

Fox entry into Tasmania

Fox entry into Tasmania has ALWAYS been a biosecurity/biodiversity risk for Tasmania, yet it is remains unclear whether foxes have established breeding populations in Tasmania.

Despite the unsubstantiated stories of intentional introductions of foxes the most likely source of single-fox introductions into Tasmania has been slack and inadequate quarantine measures. In the decades of inadequate quarantine measures at our ports, any foxes that have arrived and escaped into Tasmania, the questions remains which locations have the highest frequency of receiving fox-risk materials? Might these be the places where foxes might just get lucky and breed?

Over fifty years of 1080 use in Tasmania to control native herbivores like Bennett’s wallaby, Tasmanian pademelon and brush-tail possum coupled with the high sensitivity of red foxes to secondary 1080 poisoning (i.e. through eating a poisoned carcass) is rarely acknowledged.

Where will they ‘get lucky’ in the landscape? Closest to the farms & feedlots that have historically received container-loads of stock feed grain; agri-businesses that transport or deal with used farm equipment; freight forwarding depots. The highly reliable sighting reports of foxes in remote areas (where 1080 poisons have not been used) like the western Central Plateau or our National Parks must be the basis for intensive investigation. Maybe the remote camera used by the DFT team can be now deployed for fox studies.

It ALWAYS comes down to validating the risk assessment.

References:

- McIlroy, JC (1981) The Sensitivity of Australian Animals to 1080 Poison I. Intraspecific variation and Factors affecting Acute Toxicity. Australian Wildlife Research 8, 369-383.

- McIlroy, JC (1981) The Sensitivity of Australian Animals to 1080 Poison II. Marsupial and Eutherian Carnivores. Australian Wildlife Research 8, 385-399.

David Obendorf

With DPIW poised to embark on a decade-long $56 million dollar fox eradication campaign using 1080 meat baits as the principle eradication tool, I believe there are several very good reasons why 1080 testing of non-target Tasmanian species exposed to these baits must now be repeated. For Tasmanian wildlife authorities to rely solely on this unrepeated toxicological data would be reckless.

© The Habitat Advocate Public Domain

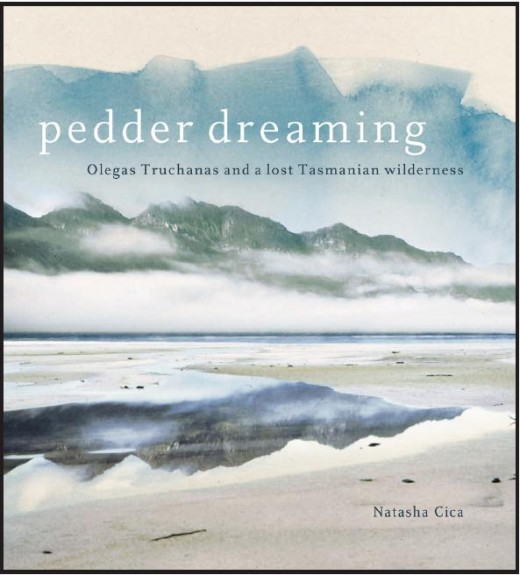

Play music, then click back to this site, zoom in to make the photos larger and scroll through this article and appreciate the magic of what was Lake Pedder.

Play music, then click back to this site, zoom in to make the photos larger and scroll through this article and appreciate the magic of what was Lake Pedder. Lake Pedder

(Photo by Olegas Truchanas (1923-1972)

Lake Pedder

(Photo by Olegas Truchanas (1923-1972)

This photo currently appropriated on the website of Tasmanian Resource Planning and Development Commission,

which as the ‘Hydro-Electric Commission’ flooded the lake in 1972 and which oddly uses the word ‘justice’ in its web address.

^http://soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/image/544/index.php

This photo currently appropriated on the website of Tasmanian Resource Planning and Development Commission,

which as the ‘Hydro-Electric Commission’ flooded the lake in 1972 and which oddly uses the word ‘justice’ in its web address.

^http://soer.justice.tas.gov.au/2003/image/544/index.php

What we destroyed… Olegas Truchanas’ children playing in Lake Pedder in Tasmania’s Southwest in 1971. Less that 12 months later it was flooded.

What we destroyed… Olegas Truchanas’ children playing in Lake Pedder in Tasmania’s Southwest in 1971. Less that 12 months later it was flooded. Fake Pedder ~ today’s drowned lake

Fake Pedder ~ today’s drowned lake

.

.

.

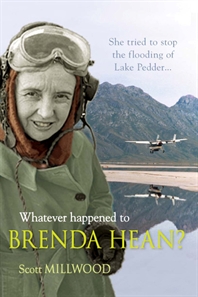

. Remembering Brenda Hean

In ‘Pedder’, Brenda had found her spiritual centre.

Remembering Brenda Hean

In ‘Pedder’, Brenda had found her spiritual centre.