Homo ‘sapiens’ – are we so wise?

The Great Grey Owl of Lapland (Strix nebulosa) – the largest owl in existence

(click to enlarge)

The Great Grey Owl of Lapland (Strix nebulosa) – the largest owl in existence

(click to enlarge)

.

‘A little knowledge is a dangerous thing‘ is a wise old proverb meaning that a small amount of knowledge can mislead people into thinking that they are more expert than they really are.

The phrase is considered originally derived from English politician and philosopher, Francis Bacon, in his literary work ‘The Essays: Of Atheism‘ of 1601, as follows:

.

“A little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion.” [1]

.

It may generally apply quite aptly across the human species. Homo sapiens sapiens is the most intelligent species on the planet. Yet given our legacy thus far, are we really much more intelligent than any other species that exists simply to breed and perpetuate its species?

Our intelligence has enabled us to successfully breed not just for survival, but to colonise the planet like no other. Yet our intelligence can only be a little more intelligent than other species, since our breeding and colonisation has grown to such an extent that it has driven other species to extinction and has destroyed much of the planet upon which we depend. While other species have a symbiotic relationship with their environment, the extent of ecological destruction that humanity has caused and continues to cause to our host planet makes us Earth’s Pathogen. A pathogen is an agent causing disease or illness to its host, such as an organism or infectious particle capable of producing a disease in another organism. Human breeding and colonisation is extreme to the extent that it is approaching 7 billion. As we exponentially breed, colonise and destroy, we destroy our host planet.

Speaking of religion, the demise and extinction of the Rapa Nui civilization on the remote Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean has become a metaphor for the self-destruction of humanity. One theory for the collapse of the Rapa Nui culture is that the Ancestor Cult that respected the dead drove the building of large stone statues (moai) to represent deified ancestors. It was believed that the living had a symbiotic relationship with the dead where the dead provided everything that the living needed (health, fertility of land and animals, fortune etc.) and the living through offerings provided the dead with a better place in the spirit world. The island’s trees were killed and used to help move these massive moai into desired position, but over time, as more moai were erected, the island’s trees were eliminated. Absolute deforestation led to the collapse of the island’s ecosystem and food supply and so to the demise of the Rapa Nui.

A second theory is that by Hunt and Lipo (2006) who found no evidence of human deforestation, or of human habitation prior to 1200. Instead, they suggest that the collapse of island society was due to the introduction of Polynesian Rats that arrived in the boats of early settlers. They hypothesize that rat population spiked at around 20 million individuals, and that these rats quickly consumed all the seeds of the native palms, leading to the collapse of the island food supply. [2]

The Moai of Easter Island,

the living faces of worshipped ancestors of the Rapa Nui people

(click to enlarge)

The Moai of Easter Island,

the living faces of worshipped ancestors of the Rapa Nui people

(click to enlarge).

.

‘Homo sapiens – time for a new name?

.

“It is high time the human race had a new name. The old one, Homo sapiens – wise or thinking man – has been around since 1758, and is no longer a fitting description for the creature we have become. When the Swedish father of taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus, first bestowed iti, humans no doubt seemed wise when compared with what scientists of the day knew about both people and other animals. We have since learned our behaviour is not quite as intelligent as we like to imagine, while some other animals are rather smart. In short, ours is a name which is both inaccurate and which promotes a dangerous self-delusion.

In a letter to Nature I am proposing there should be a worldwide discussion about the formal reclassification of humanity, involving both scientists and the public. The new name should reflect more truthfully the attributes and characteristics of the modern 21st century human, which are markedly different from those of 18th century ‘man’.

Consider the following: Humans are presently engaged in the greatest act of extermination of other species by a single species, probably since life on Earth began. We are destroying an estimated 30,000 species a year, a scale comparable to the greatest extinction catastrophes of the geological past.ii We currently contaminate the atmosphere with 30 billion tonnes of carbon equivalent every year.iii This risks an episode of accelerated planetary warming reaching 4-5 degrees by the end of this century and 8 degrees thereafter, a level which would severely disrupt food production.iv Estimates for the ultimate losses from 8of warming range from 50 to 90% of humanity.v

We have manufactured around 83,000 synthetic chemicalsvi, many of them toxic at some level, and some of which we inhale, ingest in food or water or absorb through the skin every day of our lives. A US study found newborn babies in that country are typically contaminated by around 200 industrial chemicals, including pesticides, dioxins and flame retardants.vii These chemicals are now found all over the planet, and we are adding hundreds of new ones, of unknown risk, every year. Yet we wonder why more people now die of cancer.

Every year we also release around 121 million tonnes of nitrogen, 10 million tonnes of phosphorus and 10 billion tonnes of CO2 into our rivers, lakes and oceans, many times the amounts recirculated by the Earth naturally. This is causing the collapse of marine and aquatic ecosystems, disrupting food chains and causing ‘dead zones’. More than 400 of these lifeless areas have been discovered in recent times.viii

We are presently losing about 1% of the world’s farming and grazing land every year. This has worsened steadily in the last 30 years, confronting us with the challenge of doubling food production in coming decades off a small fraction of today’s area. At the same time we waste a third of the world’s food.ix

Current freshwater demand from agriculture, cities and energy use will more than double by mid century, while resources in most countries – especially of groundwater – are drying up or becoming so polluted they are unusable.x

We passed peak fish in 2004xi, peak oil in 2006xii, and will encounter growing scarcities of other primary resources, including mineral nutrients, in coming decades. Yet demand for all resources, including food, minerals, energy and water, will more than double, especially in Asia.

Humanity spends $1.6 trillion a year on new weaponsxiii, but only $50 billion a year on better ways to produce food. Despite progress in arms reduction, the world still has around 20,000 nuclear warheads and at least 19 countries now have access to them or to the technology to make them.xiv

Finally, we are in the process of destroying a great many things which are real – soil, water, energy, resources, other species, our health – for the sake of a commodity that mostly exists in our imagination: money. While money has its uses as a medium for exchange, humanity is increasingly engaged in mass self-delusion as to what constitutes real wealth, as is quite clear from the current financial crisis.

All of these things carry the risk of catastrophic change to the Earth’s systems, making it difficult to justify our official sub-species name of Homo sapiens sapiens, or wise wise man. This not only looks like conceit, but sends a dangerous signal about our ability to manage what we have unleashed. A creature unable to control its own demands cannot be said to merit the descriptor ‘wise’. A creature which takes little account of the growing risks it runs through its behaviour can hardly be rated ‘thoughtful’.

The provisions of the International Code on Zoological Nomenclature provide for the re-naming of species in cases where scientific understanding of the species changes, or where it is necessary to correct an earlier error. I argue that both those situations now apply.

This is not just an issue for science; it concerns everybody. There needs to be worldwide public discussion about what is an appropriate name for our species, in the light of our present behaviour and attributes. Here are some names suggested by eminent Australian scientists. Marine scientist and author, Charlie Veron, suggests Homo finalis. Desert ecologist, Mark Stafford-Smith, proposes Homo quondam et futures – the once and future human. Spatial ecologist, Hugh Possingham, likes Homo nesciens – ignorant man. And atmospheric scientist, Barrie Pittock, suggests Homo sui deludens – self-deluding man.

Down the track we should not rule out an eventual return to the name Homo sapiens, provided we can demonstrate that we have earned it – and it is not mere flatulence, conceit or self-delusion. The wisdom to understand our real impact on the Earth and all life is the one we most need at this point in our history, in order to limit it. Now is the time humans get to earn, or lose forever, the title sapiens.”

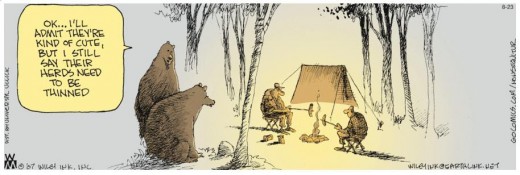

(Source: Non Sequitur – by Wiley Miller, ^http://www.gocomics.com/nonsequitur/2011/08/23)

(Source: Non Sequitur – by Wiley Miller, ^http://www.gocomics.com/nonsequitur/2011/08/23)

.

.

Editor: Globally, a material difference between Humanity and other species is that we are more intelligent at doing what other species naturally do – colonising for our own self-interest. We are Homo colonus ventosa (the conceited coloniser), or simply Homo ego ruina (self-destructive Man).

If we accept that at our current stage of evolution we have a little more knowledge than other species; and that our legacy has proven thus far to be dangerous to us, other species and to the planet, then we would be wise to seek deeper knowledge of our circumstance, of our place and of other species and the planet. The test for Humanity now is to ask what would the wise do and not do? A first step in advancing our species is to recognise that we have become Earth’s Pathogen. the second step is to recognise that we don’t know the true extent of the damage we are causing to the planet and so in the face of such uncertainty, we are wise to adopt a precautionary approach. The Precautionary Principle states: ‘When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. In this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof. The process of applying the Precautionary Principle must be open, informed and democratic and must include potentially affected parties. It must also involve an examination of the full range of alternatives, including no action.’ [4]

.

‘We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.’

~Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (1949).

The Great Grey Owl in flight

(click to enlarge)

The Great Grey Owl in flight

(click to enlarge)

.

.

References:

.

, September 2004, Vol. 25, No.9, http://multinationalmonitor.org/mm2004/09012004/september04corp1.html [>Read More]

, September 2004, Vol. 25, No.9, http://multinationalmonitor.org/mm2004/09012004/september04corp1.html [>Read More]

.

– end of article –

Tags: a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, Aldo Leopold, Earth's Pathogen, Easter Island metaphor, Great Grey Owl, Homo sapiens sapiens, human pathogen, Rapa Nui