Author Archive

Tuesday, March 27th, 2012

This article was initially written by Tigerquoll and published on CanDoBetter.net under the title ‘Selfish Murray River Rice Growers downstream continue to castrate the Snowy River‘ on 20100131

.

The Mighty Snowy The Mighty Snowy

Australia’s High Country

[Source: Adventure Pro, ^http://www.adventurepro.com.au/forums/yabbfiles/Attachments/phpePMK2XAM.jpg]

.

‘What does the Snowy River mean to Australians?

To many ancestral Australians, particularly Eastern Victorians, ‘The Snowy’ is a legendary, wild river.

To the traditional Ngarigo, Walgalu and Southern Ngunnawal people – who asked their opinion, requested their approval?

Would traditional owner’s approval been given? Likely, if open and honest, no bloody way!

The Snowy represents the untamed heart and soul of Australia’s cold frontier High Country

It is a mighty, wild river demanding respect.

But in 1950s Australia, when the colonist Government built its Hydro Scheme, it set out with disrespect to castrate this thundering stallion of a river down to a humiliating prostate trickle.’

~ Ed.

.

Our (stolen) Snowy River, reduced to a trickle

.

. .

“Gone are the days

When the Snowy was a river not just a creek.

When the snow water flushed out the entire river.

When the river was deep enough to take large sized boats and ships.

When as a youngster I had picnics on the Curlip paddle-steamer up and down the Snowy River.

When the river bank had several landings to load and unload goods and produce.

When the entrance was deep enough to be safe for all who wished to use it.

The Snowy is just like a ship that has run aground.

Both are no longer able to do what was required of them.

Having lived in Orbost – Marlo all my life

It’s a sad sight to see our Snowy water vanish over the hills to the other side.”

~ bush poem by W. B. Dreverman, born Orbost 12-1-1910.

.PS. I have worked in Orbost all my life; moved from Orbost to Marlo during 1965; now retired; my wife and I enjoy looking at the ocean and the Snowy when the tide comes in. During our lives we have seen the Snowy change from a beautiful river to a sandy bottom creek.

.

Kosciusko Main Range above the source of the Snowy River

[Source: ^http://forum.weatherzone.com.au/ubbthreads.php/topics/1095133/154] Kosciusko Main Range above the source of the Snowy River

[Source: ^http://forum.weatherzone.com.au/ubbthreads.php/topics/1095133/154]

.

Account by Charlie Robertson, born in 1919 at Dalgety:

.

“I lived one kilometre from the Snowy River for most of my life.

We could always hear the Snowy singing from home. That is how I used to describe the sound of the river. It used to be quieter in the summer. Now we don’t hear it at all. You wouldn’t know there was a river there now. It was a clear river most of the time, 99 per cent pure. It’s hard water now. Before it was soft.

The river had a gravelly sandy bed with rocks and boulders but they’re overgrown now and you can’t see them. During the spring thaw it used to flow for three months at least in a good strong flow, bank to bank. The level used to be up into the first ring on the pylon for that period.”

…It was a very popular river for fishing. You could see the fish from the bridge. You could just about get to the river anywhere you wanted with some exceptions. Now you can hardly get to it for the weeds, willows and blackberries.

When the river was dammed there was nothing to fish. There was no fish in the dams just after they were built. I have been up there and it doesn’t interest me at all, especially when you’ve spent much of your life fishing the river. It’s a different kind of fishing all together. I used to fish at night for native fish.

They are all gone now. I gave up fishing when they dammed the river. “

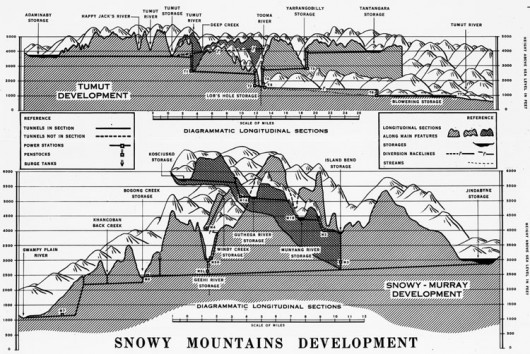

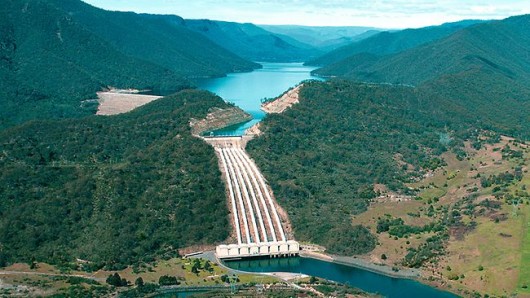

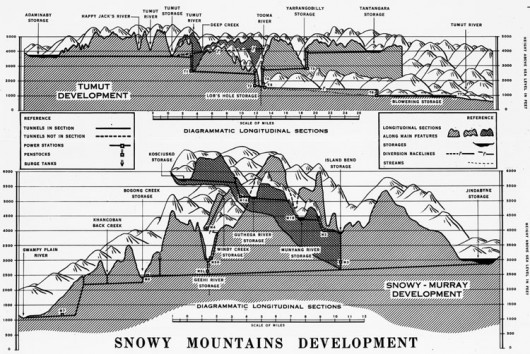

The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme is the most complex, multi-purpose, multi-reservoir hydro scheme in the world with 80 kilometres of aqueducts, 140 kilometres of tunnels, 16 large dams and seven power stations, two of which are underground. The project was drievn by then Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley. It commenced under an Act of Federal Parliament in October 1949 with the goal of diverting the Murrumbidgee, Snowy and Tumut Rivers in south western NSW essentially to provide irrigation water for the western side of the Great Dividing Range, and in the process generate hydro-electric power. This irrigation facilitated settlement of mass immigration.

.

Account by Pip Cogan, born in 1913 at Dalgety and resident 85 years, a grazier:

.

“The Snowy River was part of my life until it was dammed.

I had fished the river since I was a young fellow action against the NSW Government for failing to honour a five-year review of the Snowy Hydro Corporation’s water licence. The Alliance is arguing the legal provisions allowing the Mowamba water flow to be increased without compensationary payments.

It is clear from reading the Snowy Scientific Committee’s three reports so far that the Snowy upper reaches are sick, despite the $425 million agreement in 2002 by three governments to restore it. Sacrificed long ago to humanity’s needs for hydroelectricity and irrigation water for the Murray Darling food bowl, in drought the river has become so deprived of lusty water flow that its cobbles do not turn over. Its deep pools alienate life forms, forbiddingly hot on top and cold on the bottom.

Last month the scientific committee warned the NSW Government that the limited environmental flows allowed from Snowy Hydro dams provide mere ”life support” for plants and animals in the river.”

The continued demise of the magnificent Snowy River is attributed to the political influence of the long downstream self-interested rice growers, cotton growers and citrus and grape growers, all wholly artifically dependent on irrigation from the Murray River, fed by the Snowy River upstream.

But such exploitive irrigation-dependent industries have powerful political friends like the Australian Government Rural Industries Research and Dever the way that it was and it to look at it today is simply heartbreaking.”

The Snowy River was dry as a bone at Island Bend Dam in February 2010.

(Snowy River Alliance: Louise Crisp)

The Snowy River was dry as a bone at Island Bend Dam in February 2010.

(Snowy River Alliance: Louise Crisp)

.

Account by Kevin Schaefer, born 1925 at Dalgety, resident for 73 years:

.

“The Snowy River was a real river.

In the spring the river flowed very strong after the snow melt. This strong flow existed for many months, usually from August to November. Whilst the spring was characterised by strong flows, the Snowy River could have heavy flows or flooding any time of the year. For example the biggest flood in my lifetime occurred in the summer of 1934.

All the mountain water came down here. The Snowy River’s water was clean and pure.

In fact when you drank it, you couldn’t get enough of it. I can remember the years between 1949 and 1956 as being particularly wet, with a peak in river flow in March 1950 when it flooded. The river could rise and fall all year round depending on the rainfall.

In my lifetime I never saw the river any where near as low as it has been since the damming. …I haven’t seen the platypus like I used to. You could see colonies of platypus along the river before.

Now you’re lucky to see one.”

.

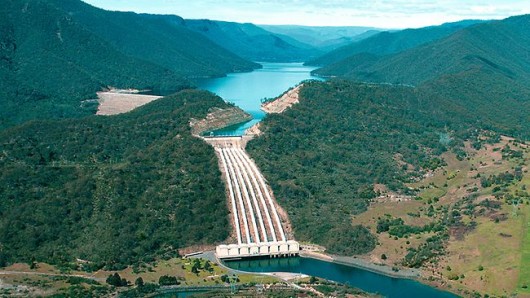

Talbingo Dam artificially flooded the Snowy River

(‘Tumut 3’ Power Station below) Talbingo Dam artificially flooded the Snowy River

(‘Tumut 3’ Power Station below)

.

The Snowy River Alliance down here in Victoria is right. Australia’s most famous wild river, the Snowy River, deserves to have its natural flows restored.

The Alliance argues that if the Hydro schemers release just a third of the Snowy’s original flows, its ecology could be restored. But the current life sucking 5% dished out by the Snowy Hydro Ltd corporation is exploitative, selfish and wrong.

The Snowy River Alliance, according to Glenice White of Orbost, deep in Victoria’s East Gippsland, started off back in 1971 as a reaction to the Snowy’s “pronounced signs of degradation“. This local community reaction culminated in the Snowy River Interstate Catchment Co-ordinating Committee Report, which outlined the problems of the river and its catchment and made a number of recommendations including that more water was required to improve the river’s ecology.

It soon became apparent to the Snowy River community that the Snowy Hydro was steering the river’s water to the irrigation agriculturalists down the Murray River, trying to artificially grow rice, citrus and grapes in an otherwise parched hot semi-arid climate.

.

Whereas the much hyped electricity generation in reality became a small part of the operation.

Instead of supplying 17% of the South Eastern Grid as the Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Authority would want the public to believe,

it supplies only 4-5%.

.

The propaganda from the Authority is not only misleading but downright wrong.

Since the Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Scheme of the 1950s, the choice of water allocation has always been political. The construction of the Jindabyne Dam in 1967 destroyed the 150 year old local community of Dalgety, which had the Snowy running wild through the town.

.

Dalgety’s fresh water supply was reduced to a token 1% flow!

The township of Dalgety has not recovered to this day.

The original townships of Adaminaby, Jindabyne and Talbingo were inundated by the Hydro Scheme.

These communities deserve not to be forgotten

Nor the millions of hectares of dismissed wildlife habitat, flooded for irrigation of exotic crops.

.

In 1996 a report commissioned and prepared by the NSW Department of Land and Water Conservation, Victorian Department of Natural Resources and Environment (now the Department of Sustainability and Environment) and the Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Authority recommended that a minimum of 28% of the original flow that passed Jindabyne before the dams were built, be reinstated to the river.

A key perception problem is that Hydro industrialists argue that any water not piped to hydro-electricity or to fill dams is wasted water flow that just runs into the sea. These water industrialists reject the concept of ecological river flows as barbarian. Then recently, the Snowy River Alliance has flagged the opening of the Mowamba River which is a headwater tributary to the Snowy. Currently, it is captured by a weir where it is whipped away via an aqueduct to Lake Jindabyne.

Lake Jindbyne is a flooded Snowy River Lake Jindbyne is a flooded Snowy River

.

An article, ‘Standoff over the Snowy’ by Debra Jopson, 30-Jan-10, (Fairfax media) has highlighted that the Snowy River Alliance plans legal action against the NSW Government for failing to honour a five-year review of the Snowy Hydro Corporation‘s water licence. The Alliance is arguing the legal provisions allowing the Mowamba water flow to be increased without compensationary payments.

It is clear from reading the Snowy Scientific Committee’s three reports so far that the Snowy upper reaches are sick, despite the $425 million agreement in 2002 by three governments to restore it.

Sacrificed long ago to humanity’s needs for hydroelectricity and irrigation water for the Murray Darling food bowl, in drought the river has become so deprived of lusty water flow that its cobbles do not turn over. Its deep pools alienate life forms, forbiddingly hot on top and cold on the bottom. Last month the scientific committee warned the NSW Government that the limited environmental flows allowed from Snowy Hydro dams provide mere ‘‘life support” for plants and animals in the river.

The continued demise of the magnificent Snowy River is attributed to the political influence of the long downstream self-interested rice growers, cotton growers and citrus and grape growers, all wholly artifically dependent on irrigation from the Murray River, fed by the Snowy River upstream.

A diverted river A diverted river

.

But such exploitive irrigation-dependent industries have powerful political friends like:

- The Australian Government Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation

- The Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (whatever its latest political reincarnation)

- Ricegrowers Association of Australia

- SunRice

- Rabobank

- Wesfarmers Federation Insurance

- CopRice

- Rice Marketing Board of NSW

- Go Grains Health & Nutrition Ltd

- Coleambally Irrigation

- Goulburn-Murray Water

- Murray Irrigation Limited

- Snowy Hydro

- NSW Irrigators’ Council

- Snowy Mountains Engineering Corporation

- The Kondinin (agricultural) Group

- Cotton Australia

- NSW Farmers’ Association

- National Farmers’ Federation

- The Australian Rural Leadership Program

- amongst others.

Upper reaches of The Snowy Upper reaches of The Snowy

.

‘Dairy industry is a big environmental burden’

(comment by Milly on CanDoBetter.net, 20100131):

.

Dairy exports make Australia one of the world’s largest exporter of virtual water, despite it being one of the driest continents on the planet! Dairy production takes place in all states, but it is particularly significant in Victoria, where more than 60 per cent of all dairy farming enterprises are located. The number of dairy farms has declined steadily over recent decades, but the industry is trending towards larger and intensive farming.

Approximately 569 GL/year is transferred across from the Snowy River Basin and released to the Murray River upstream of Hume Reservoir. Fifty percent of this water is allocated to the Victorian River Murray diverters. The other fifty percent is allocated to New South Wales. Dairying is the heaviest user of irrigated water, often requiring irrigated pasture.

Hume Weir

..dammed and flooded the Murray and Mitta Rivers to create artificial Lake Hume for irrigation farming. Hume Weir

..dammed and flooded the Murray and Mitta Rivers to create artificial Lake Hume for irrigation farming.

.

Constructed over a 17-year period from 28 November 1919 to 1936 with a workforce of thousands, a branch siding from the Wodonga – Cudgewa railway was built to supply materials. It was extended during the 1950s, and completed in 1961, necessitating the wholesale removal of Tallangatta township and its re-establishment at a new site eight kilometres west of the original, as well as railway and road diversions.

In 2007 Japanese beverage giant Kirin acquired dairy processor National Foods for $2.8 billion. The emergence of large multi-national companies as significant players in the Australian dairy industry was forcing producers to bulk up to larger farms. Dairy Australia’s managing director Mike Ginnivan said the industry would remain a major user of water in the Murray Darling Basin for at least the next 10 years and would necessitate continued improvements in water use efficiency. By banning the export of dairy products and reducing our own consumption we may have a chance to save our ailing river systems!

Close to the source of the Snowy River

[Source: ^http://unauthorised.org/ronni/bioregion/rivers.html]

. Close to the source of the Snowy River

[Source: ^http://unauthorised.org/ronni/bioregion/rivers.html]

.

‘The Snowy Hydro Con – it was all about mass irrigation and mass immigration’

.

Since Australia’s Gold boom and the exponential immigration growth it attracted, European colonists had dreamed of controlling the seasonally flooding rivers of the ranges along eastern Australia into dams, in order to provide reliable irrigation to harvest inland plains for agriculture and resist Australia’s periodic long droughts – i.e. provide for ‘drought security‘.

The wild Snowy River was long regarded by many European colonists as a wasted resource, because it flowed to the sea through country that was already well watered. Proposals to divert the river for irrigation and power generation were presented from as early as the 1880s but it was not until the 1940s that the necessary resources and technological capacity were realised with the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

In 1949, the Chifley Labor Government was enraptured with its post-War ‘populate or perish‘ mantra. It embarked on Australia’s greatest immigration scheme and channelled 100,000 migrant jobs into building the Snowy Mountains Hydro Scheme and designated the Riverina Region to mass agricultural settlement and production. The Government decided to dam the snow-fed headwaters of the east flowing Snowy River and divert them into the Murray River, which heads west through farmland along the NSW-Victoria border.

Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley (1945-49) Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley (1945-49)

.

Construction started on 17 October 1949, when the Governor General Sir William McKell, Prime Minister Ben Chiffley and the Scheme’s first Commissioner, Sir William Hudson, fired the first blast at Adaminaby. The Snowy River was finally dammed twice: first at its headwaters at Island Bend in 1965, and again downstream at Jindabyne in 1967.

After Lake Jindabyne was created, 99% of the river’s water was retained and diverted for power generation and irrigation.

The Chifley Labor Government promised the Snowy Hydro Scheme would deliver ‘cheap hydro-electric power‘ but when completed in 1974, the Snowy Mountains Scheme had cost $1.16 Billion (Ed: equivalent to perhaps $5 Billion in 2012 money – ^http://www.dollartimes.com/calculators/inflation.htm).

[Source: ^http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/australia_innovates/?behaviour=view_article&Section_id=1020&article_id=10047]

.

The Snowy Mountains Hydro Scheme (since abbreviated to ‘Snowy Hydro‘) consists of 16 major dams; 7 power stations; a pumping station; and 225 kilometres of tunnels, pipelines and aqueducts in the high country of New South Wales and Victoria .

The amount of electricity Snowy Hydro generates has always depended upon winter rains and mountain snow falls. So, in times of drought, hydro output drops significantly. Snowy Hydro is dependent upon how much snow falls on the Australian Alps, and therefore how much water goes into predominantly lakes Eucumbene and Jindabyne. In 2004-05, Snowy Hydro’s output was just 4,388 GWh (13.5% capacity) during a time of prolonged drought.

[Source: ‘Why Snowy prefers to keep its water’, by Alan Kohler, 20060524, ^http://www.smh.com.au/news/business/why-snowy-prefers-to-keep-its-water/2006/05/23/1148150255347.html]

.

As at 20111128, NSW hydro-electric power stations include four in the Snowy Scheme plus one at Shoalhaven and another at Warragamba:

- Blowering (Snowy Hydro) 80 MW

- Guthega (Snowy Hydro) 60 MW

- Murray (Snowy Hydro) 1500 MW

- Tumut (Snowy Hydro) 2116 MW

- Shoalhaven (Eraring Energy) 240 MW

- Warragamba (Eraring Energy) 50 MW

.

[Source: ‘Electricity generation’, NSW Government, ^http://www.trade.nsw.gov.au/energy/electricity/generation]

.

Of the current 18,000 megawatts (MW) of installed electricity generation capacity of New South Wales, Snowy Hydro provides about 20% of NSW electricity, mainly to supply the additional power needed in morning and evening peak use. Victoria’s hydroelectricity is sourced from the state’s major dams, including Lake Eildon, Hume and Dartmouth. Overall, Snowy Hydro provides 17% of the electricity for south-eastern Australia and 5% of Australia’s total electricity generation (2007-08).

[Source: ‘Hydroelectricity’, Victorian Government, ^http://www.dpi.vic.gov.au/energy/sustainable-energy/hydroelectricity]

.

Tumut Pond Dam at Cabramurra Tumut Pond Dam at Cabramurra

.

The Snowy Mountains Scheme diverted and stopped the natural flows of major rivers including the Snowy and Tumut rivers. It caused irrevocable damage to a natural cherished landscape. It created the Murray Irrigation Area and the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area which have collectively since been referred to as the Riverina, sustaining dozens of agricultural communities. In 1968 an entire town, Coleambally, was created as a result of the new flow of water. Main cropping includes stone fruit, grain, and rice.

Murrumbidgee River Catchment

[Source: ^http://www.kathleenbowmer.com.au/pubs/fenner030531.htm] Murrumbidgee River Catchment

[Source: ^http://www.kathleenbowmer.com.au/pubs/fenner030531.htm]

.

Over the decades, deforestation and excessive irrigation of the region has raised the salt table and caused extensive to dry land salinity, undermining the viability of irrigated cropping.

Dry Land Salinity

..caused by clearfell deforestation and excessive irrigation Dry Land Salinity

..caused by clearfell deforestation and excessive irrigation

.

‘Beautiful memory of The Snowy’

Comment by ‘Quark’ on CanDoBetter.net, 20100131:

.

In 1975 I visited the Snowy with friends and camped in the area.

I remember swimming in the river. The water was about 1.5 metres deep, very clear with smooth white pebbles and rocks on the bottom. It was so clean and soft that I was drinking it as I swam and I remember thinking that my immersion in this element at that moment was sheer perfection. There was no-one else around.

This post dates the damming of the river but maybe they had let more water through and the irrigation demands were less than they are now.

More than a decade before when I was at school, one of our prescribed books was “Above the snow line”- a novel about the Snowy project and the immigrant workers. That was my introduction to this feat of engineering. I don’t recall the environmental impacts ever being discussed in class.

The following year my parents took me up to see the Snowy project on a guided motoring tour – I recall high dam walls turbines and things which meant little to me. I wouldn’t have known what had been lost in the creation of this scheme. I still have coloured photographs (slides) of this trip.

It was 1962.

Snowy River

[Source: ^http://forum.weatherzone.com.au/ubbthreads.php/topics/1095133/154] Snowy River

[Source: ^http://forum.weatherzone.com.au/ubbthreads.php/topics/1095133/154]

.

‘Bugger the bush mentality’

Comment by Tigerquoll on CanDoBetter.net, 20100201:

.

Thanks Milly & Quark for your feedback.

Agriculture that profits from robbing resources (like potable water) from one region is inequitable. The Murray Valley, Riverina and Murray Darling irrigation regions are robbing Australia’s Alpine region of its water for artificial agriculture that is out of synch with its climate and so wholly dependent on artificial resources – water, fertilizer insecticides and GM.

It is State-sanctioned river theft underwritten by corrupt cronyism where politicians meter out favours to influential lobbyists that justify their claim on providing Australian export revenue and jobs – be it drought rice growers, drought citrus growers, drought orchards, drought dairy farmers. And then they give us the dust storms as their topsoil is eroded. Why do we need so much milk, cheese and yoghurt on our supermarket shelves anyway? The supply is excessive to the extent that it is exported, so our primary industry policy has us ruining the Australian environment (river depletion, irrigation salinity/acidification) for export revenue. Primary Industry policy clearly has ripped up Triple Bottom Line accountability.

In 1975, I visited the Snowy with friends and camped in the area. I remember swimming in the river. The water was about 1.5 metres deep, very clear with smooth white pebbles and rocks on the bottom. It was so clean and soft that I was drinking it as I swam and I remember thinking that my immersion in this element at that moment was sheer perfection. There was no-one else around.

Spring Street will argue the food bowl utilitarian justification that river water from the bush is needed to feed the urban millions swelling from more arriving at Tullamarine like ants out of a nest. Only the human test is applied to resource allocation. The locals in the bush are ignored because the millions of votes are increasingly in the cities.

Quark, traditional Australian values like fresh stream water have been forgotten in urbane Australia. Melbourne’s water used to be the best. Now it is metallic with all the additives. Now they are ruining the Wonthaggi region and buggering its locals to cater for a desal plant for monstrous Melbourne.

The Snowy Scheme history should be re-written from the point of view of the promises versus the outcomes, and from the point of view of the benefits with the costs, and from the point of view of the national economy versus the local destruction.

.

Australian 1950s politicians just copied big brother America, to emulate its hydro ‘progress’.

.

Most of the employment went to immigrants. The sixteen dams were to provide irrigation to the Riverina and Murray-Goulburn to create a food bowl to feed a growing Melbourne and Sydney fuled by massive immigration. The turbine generated electricity was a secondary output. The seven power stations supply only 10% of the electricity for VIC and NSW, mush of which is lost over the hundreds of kilometres of transmission lines that have scarred many fragile ecosystems.

.

The justification that Hydro-electricity is clean, efficient and renewable energy is wrong.

The Snowy Hydro Scheme cost $820 million (‘billion’ in 2012 money) and destroyed vast river valleys.

.

Building a dam effectively decommissions a wild river and the ecosystems it supports. The environmental damage is irreversible. Irreversible damage is not clean and not renewable. The only renewable aspect of hydro is rain re-filling artificial dams. Rivers are a non-renewable resource and the classification of hydro as a “renewable” energy source is a misnomer.

It’s a bugger the bush mentality.

.

Tiger Quoll

Suggan Buggan

Snowy River Region

Victoria 3885

Australia

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘ Oral history of the Snowy River‘, Snowy River Alliance, ^ http://www.snowyriveralliance.com.au/reports/snowy%20enquiry/chap2.html

.

[2] Snowy Water Enquiry 1998, ^ http://www.snowyhydro.com.au/levelTwo.asp?pageID=44&parentID=6

(Note: Link since deleted by Snowy Hydro – this is what it read:

‘The Snowy Water Inquiry was commissioned in 1998 with a brief to recommend environmental water release options to the Commonwealth, Victorian, and NSW Governments so that corporatisation of the Snowy Mountains Scheme could proceed. These release options related to the Snowy River below Jindabyne, the Murray River and other rivers associated with the Scheme. The Inquiry objectives were that the recommendations would not adversely impact on water supplies to existing irrigators or the viability of the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

The Commonwealth, Victorian and NSW governments will contribute $375 million over ten years to fund water-saving efficiency initiatives associated with the Murray and Murrumbidgee Irrigation Systems. These water-saving initiatives will subsequently reduce the amount of water to be released from the Scheme to the Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers, thus allowing increased releases to the Snowy River below Jindabyne.

Environmental releases from the montane rivers will be equivalent to 150 GWh (gigawatt hours) of lost energy production from the Scheme each year. These releases are to be implemented at a similar rate to the releases to the Snowy River from Jindabyne. The combined impact of the Snowy, Murray and montane river releases will reduce generation from the Scheme by up to 540 GWh per year or an average of 11%.

Substantial outlet works have been built at Jindabyne and Tantangara Dams to allow for the environmental releases. Minor modifications to a number of aqueducts was also required to enable the environmental releases from the montane rivers to be implemented and measured.

Snowy Hydro is committed to the future of the Snowy Mountains Scheme and river health, while meeting the primary role of supplying renewable energy and water for irrigation.

Healthy rivers are vital to the Snowy Mountains Scheme for many reasons – our prosperity, our environment, our communities and our future depend on it.’

.

The Snowy Water Inquiry Outcomes Implementation Deed (SWIOID), ^www.water.nsw.gov.au [>Read Deed]

.

[3] Snowy River Alliance, ^http://www.snowyriveralliance.com.au/

.

[4] Man from Snowy River Museum, Corryong, Victoria’s High Country ^http://www.manfromsnowyrivermuseum.com/home/index.htm

.

[5] ‘Snowy River in dire straits‘, Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), Broadcast: 20100401, Reporter: Emma Griffiths, ^http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/content/2010/s2863039.htm

.

‘The massive floodwaters flowing out of Queensland into western New South Wales have revitalised the parched Murray Darling Basin – but the ailing snowy river in southern New South Wales won’t see a drop.’

.

Transcript:

.

KERRY O’BRIEN, PRESENTER: The massive floodwaters flowing out of Queensland into Western New South Wales are in the process of revitalising parts of the parched Murray-Darling basin at least.

But the ailing Snowy River in southern New South Wales won’t see a drop. Its survival depends on water released from the massive Snowy Hydro system of dams, at the say-so of the New South Wales Government.

This past summer those flows have hit a high-water mark, with the biggest releases rushing down the Snowy since the hydro scheme was built in the 1960s. But conservation groups say it hasn’t made up for the years of political neglect and broken promises that they say have left the Snowy in dire straits.

.

Emma Griffiths reports.

JOHN GALLARD, SNOWY ALLIANCE: They said they were going to fix it. They haven’t fixed it.

SAM WILLIAMSON, BUSINESSMAN: We haven’t got a lot of water and everybody wants it, so who gets it? That is the fight at the moment isn’t it? Who gets the water?

EMMA GRIFFITHS, REPORTER: The Snowy River starts with a trickle in the highest of Australia’s High Country. Its tributaries form rocky creeks that gather in pace until they hit the massive system of dams and weirs that form the Snowy Hydro scheme, but this year the river has roared again.

JOHN GALLARD: We need a lot more flows like this to make the whole process worthwhile.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: John is a former park ranger. In retirement, the Snowy River has become his obsession.

JOHN GALLARD: It will make a little bit of a difference but it’s only a very small amount of water by comparison with what is needed.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: For two days this year the water has burst free of Jindabyne Dam.

In the biggest release since the Snowy scheme was built, 870 megalitres each day have flowed down the river. The extraordinary release was prompted by dire scientific warnings that isolated pools downstream were in danger of becoming stagnant.

JOHN GALLARD: It would be beautiful to have it every day but I don’t think there is any likelihood of that happening in the near future.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: Those who want to protect the river thought they had already fought the battle to save the Snowy and won.

Eight years ago the Commonwealth, along with Victoria and New South Wales, promised to let more water flow down the river purely for environmental reasons. But since then, the activists say, that promise has been forgotten and the Snowy is in worse trouble than ever.

JOHN GALLARD: You’ve got sections of river up there now that are totally dry for a major part of the season.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: Back in 2002 the governments in charge of the Snowy made a major political announcement. They closed the weir on one of the river’s main tributaries, the Mowamba. With much fanfare, then Premiers Bob Carr and Steve Bracks donned waders, unveiled a plaque and inspected the outcome of their decision – freely flowing water.

But three years later the weir was back in operation. The authorities say that was always the plan and now the river is again but a dribble.

JOHN GALLARD: Everybody thought it was going to be gone forever and we were going to have a free flowing river eventually. So you know, we are back to square one.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: One man who was there that day had doubts from the start.

SAM WILLIAMSON: I think eight years ago they were probably dreaming that it may rain, that we might have record snow falls. Maybe it was worth the promise, maybe not.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: Steve Williamson has been casting a line into the waters of the Snowy Mountains for more than 35 years and he has built successful fishing business out of the hobby he loves.

He doesn’t blame the politicians for the river’s woes. He doesn’t blame the Snowy Hydro. For him, the culprit is the drought.

SAM WILLIAMSON: There is only so much water in the glass and everybody wants – needs to learn to share it.

PHILIP COSTA, NSW WATER MINISTER: The best solution is for it to rain then we will all be very happy. It will certainly make my job a lot easier.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: As the New South Wales Water Minister, Philip Costa is the man largely responsible for determining who gets what out of the Snowy River system.

PHILIP COSTA: Some critics sometimes don’t accept the fact that we are in a drought. We are in a very severe drought. The drought has been around for some time now and what we have been doing is we have been putting water – as is the case now – down through the system when we can. When we have the available water.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: That political pledge eight years ago also centred on a commitment to increase the Snowy’s water allocation to 15 per cent of its original flows by this year. But the reality has fallen far short.

We’re getting 4 per cent – that’s all we are getting. That’s all we’ve got for 7 years since they have made the first environmental releases.

Unfortunately all of the agreements that they’ve made, we’ve found out are non-binding agreements.

PHILIP COSTA: We haven’t met what all the expectations might be simply because there isn’t enough water but we have delivered water to all of those discrete users and we do levit (phonetic) it in an equitable way. No one is getting more water than their share.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: The Murray River is a key beneficiary of the Snowy Hydro Scheme and those on the Eastern fall can’t help feeling short changed.

JOHN GALLARD: They’ve forgotten about the Snowy and now they’re saying to everybody they’re going to fix the Murray Darling system.

My comments are, this was the litmus test. They haven’t fixed this one, how are they possibly going to fix the Murray Darling system? They couldn’t even get the Snowy right.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: The Snowy River campaigners are determined to keep on fighting. But they have long ago recognised that even with more water and promised political action, they will never see the Snowy return to its glory days.

JOHN GALLARD: It’s a different river altogether. It’s a senile, old geriatric river now, whereas once it was very dynamic and quite dramatic. But it can be a relatively healthy river again and it can be much better than it is now.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: For some, the only solution is a hope shared Australia wide

SAM WILLIAMSON: The positive is it is going to rain one day, hopefully.

EMMA GRIFFITHS: And that’s what you are praying for?

SAM WILLIAMSON: We’re praying for it. That’d keep everybody happy.

KERRY O’BRIEN: That report from Emma Griffiths.

.

Blowering Dam of the Tumut River, New South Wales, part of the Snowy Mountains Scheme. Blowering Dam of the Tumut River, New South Wales, part of the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

Completed in 1968, the Blowering Dam holds 1,628,000 megalitres used for irrigation along the Murrumbidgee River, Yanco/Colombo/Billabong Creeks system, the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area and the Colleambally Irrigation Area.

The Blowering Power Station delivers electricity generation capacity of just 80 megawatts (MW), which is 0.004% of the total electricity capacity of New South Wales (18,000 MW).

.

[6] ‘Snowy River back to a trickle – water turned off‘, Exploroz.com website, Comment submitted: Monday, Feb 20, 2006 at 16:46, by Member – Willie , Epping .Syd., ^http://www.exploroz.com/Forum/Topic/30970/SNOWY_RIVER_BACK_TO_A_TRICKLE_-_WATER_TURNED_OFF.aspx

.

‘The Sydney Morning Herald Feb 18-19 carried a full page article on the fact that the flow in the Snowy River in February dropped from 275 megalitres to 70 overnight when the Hydro Scheme diverted the water from the Mowamba River back into their dams .

The SMH says no one new this was going to happen , but after doing some research and going to the site , ^http://www.snowyriveralliance.com.au/newsletter.htm#3

it appears that at least the people in the Snowy River Alliance new about it and had been making submissions to the Government to stop the flow being redirected in February .

Does anybody know the real story behind this ? Putting water back into the Snowy is a great project and I would like to try and help them somehow .

Cheers ,

Willie .

.

[7] ‘Reflections of a River‘ – The Snowy River, ^http://www.thesnowyriver.com/

.

…”While most of the river runs through country that is largely uninhabited, the majority being protected by the Snowy River National Park, it’s flow was drastically reduced to less than 1% when the construction of The Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Scheme was completed in the 1970′s.

Today the river is but a shallow of it’s former self.

It’s significance to Australian folk lore due to Banjo Patterson’s poem – The Man from Snowy River – establishes The Snowy River as a important part of our national identity.”

.

The natural Snowy River

Circa 1890 The natural Snowy River

Circa 1890

.

[8] The making of a legend…

.

‘The Man from Snowy River’

by A.B. “Banjo” Paterson

.

There was movement at the station, for the word had passed around

That the colt from old Regret had got away,

And had joined the wild bush horses – he was worth a thousand pound,

So all the cracks had gathered to the fray.

All the tried and noted riders from the stations near and far

Had mustered at the homestead overnight,

For the bushmen love hard riding where the wild bush horses are,

And the stockhorse snuffs the battle with delight.

.

There was Harrison, who made his pile when Pardon won the cup,

The old man with his hair as white as snow;

But few could ride beside him when his blood was fairly up –

He would go wherever horse and man could go.

And Clancy of the Overflow came down to lend a hand,

No better horseman ever held the reins;

For never horse could throw him while the saddle girths would stand,

He learnt to ride while droving on the plains.

.

And one was there, a stripling on a small and weedy beast,

He was something like a racehorse undersized,

With a touch of Timor pony – three parts thoroughbred at least –

And such as are by mountain horsemen prized.

He was hard and tough and wiry – just the sort that won’t say die –

There was courage in his quick impatient tread;

And he bore the badge of gameness in his bright and fiery eye,

And the proud and lofty carriage of his head.

.

But still so slight and weedy, one would doubt his power to stay,

And the old man said, “That horse will never do

For a long a tiring gallop – lad, you’d better stop away,

Those hills are far too rough for such as you.”

So he waited sad and wistful – only Clancy stood his friend –

“I think we ought to let him come,” he said;

“I warrant he’ll be with us when he’s wanted at the end,

For both his horse and he are mountain bred.

.

“He hails from Snowy River, up by Kosciusko’s side,

Where the hills are twice as steep and twice as rough,

Where a horse’s hoofs strike firelight from the flint stones every stride,

The man that holds his own is good enough.

And the Snowy River riders on the mountains make their home,

Where the river runs those giant hills between;

I have seen full many horsemen since I first commenced to roam,

But nowhere yet such horsemen have I seen.”

.

So he went – they found the horses by the big mimosa clump –

They raced away towards the mountain’s brow,

And the old man gave his orders, “Boys, go at them from the jump,

No use to try for fancy riding now.

And, Clancy, you must wheel them, try and wheel them to the right.

Ride boldly, lad, and never fear the spills,

For never yet was rider that could keep the mob in sight,

If once they gain the shelter of those hills.”

.

So Clancy rode to wheel them – he was racing on the wing

Where the best and boldest riders take their place,

And he raced his stockhorse past them, and he made the ranges ring

With the stockwhip, as he met them face to face.

Then they halted for a moment, while he swung the dreaded lash,

But they saw their well-loved mountain full in view,

And they charged beneath the stockwhip with a sharp and sudden dash,

And off into the mountain scrub they flew.

.

Then fast the horsemen followed, where the gorges deep and black

Resounded to the thunder of their tread,

And the stockwhips woke the echoes, and they fiercely answered back

From cliffs and crags that beetled overhead.

And upward, ever upward, the wild horses held their way,

Where mountain ash and kurrajong grew wide;

And the old man muttered fiercely, “We may bid the mob good day,

No man can hold them down the other side.”

.

When they reached the mountain’s summit, even Clancy took a pull,

It well might make the boldest hold their breath,

The wild hop scrub grew thickly, and the hidden ground was full

Of wombat holes, and any slip was death.

But the man from Snowy River let the pony have his head,

And he swung his stockwhip round and gave a cheer,

And he raced him down the mountain like a torrent down its bed,

While the others stood and watched in very fear.

.

He sent the flint stones flying, but the pony kept his feet,

He cleared the fallen timber in his stride,

And the man from Snowy River never shifted in his seat –

It was grand to see that mountain horseman ride.

Through the stringybarks and saplings, on the rough and broken ground,

Down the hillside at a racing pace he went;

And he never drew the bridle till he landed safe and sound,

At the bottom of that terrible descent.

.

He was right among the horses as they climbed the further hill,

And the watchers on the mountain standing mute,

Saw him ply the stockwhip fiercely, he was right among them still,

As he raced across the clearing in pursuit.

Then they lost him for a moment, where two mountain gullies met

In the ranges, but a final glimpse reveals

On a dim and distant hillside the wild horses racing yet,

With the man from Snowy River at their heels.

.

And he ran them single-handed till their sides were white with foam.

He followed like a bloodhound on their track,

Till they halted cowed and beaten, then he turned their heads for home,

And alone and unassisted brought them back.

But his hardy mountain pony he could scarcely raise a trot,

He was blood from hip to shoulder from the spur;

But his pluck was still undaunted, and his courage fiery hot,

For never yet was mountain horse a cur.

.

And down by Kosciusko, where the pine-clad ridges raise

Their torn and rugged battlements on high,

Where the air is clear as crystal, and the white stars fairly blaze

At midnight in the cold and frosty sky,

And where around The Overflow the reed beds sweep and sway

To the breezes, and the rolling plains are wide,

The man from Snowy River is a household word today,

And the stockmen tell the story of his ride.

.

~ The Bulletin, 26 April 1890.

.

In memory of Jack Riley In memory of Jack Riley

.

Audio Readings of this magnificent pioneer poem:

.

[a] Australia’s Jack Thompson’s reading: ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqyP3eKJ8p0

.

[b] Another reading: ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fs_-DKUimeo

.

Tags: Coleambally Irrigation, CopRice, Cotton Australia, Dalgety, Go Grains Health & Nutrition Ltd, Goulburn-Murray Water, Island Bend Dam, Jindabyne Dam, Murray Irrigation Limited, National Farmers’ Federation, NSW Farmers’ Association, NSW Irrigators’ Council, Rabobank, Rice Marketing Board of NSW, Ricegrowers Association of Australia, Snowy Hydro, Snowy Hydro Corporation, Snowy Hydro Scheme, Snowy Mountains Development, Snowy Mountains Engineering Corporation, Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Authority, Snowy River, Snowy River Alliance, Snowy River Basin, SunRice, The Australian Rural Leadership Program, The Kondinin Group, The Man from Snowy River, Wesfarmers Federation Insurance

Posted in Gippsland (AU), Threats from Farming, Threats from Hydro and Dams | 4 Comments »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Wednesday, March 21st, 2012

When Coal Seam Gas fracking contaminates underground aquifers When Coal Seam Gas fracking contaminates underground aquifers

.

Since 2008, Anna Bligh’s Queensland Labor Government has encouraged and welcomed the establishment of Coal Seam Gas (CSG) across Queensland with open arms…

“The Queensland Government welcomes the establishment of a new energy industry, which diversifies our State’s fuel mix and capitalises on our state’s extensive coal seam gas (CSG) reserves to meet the growing global demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG). The LNG industry provides Queensland with an exciting opportunity to create new jobs in our regional centres, affected by the recent downturn in resource exports, and increases the potential prosperity of all Queenslanders through greater export revenue and royalty payments.”

[Source: ^http://www.industry.qld.gov.au/documents/LNG/Blueprint_for_Queenslands_LNG_Industry.pdf [>Read LNG Blueprint]

.

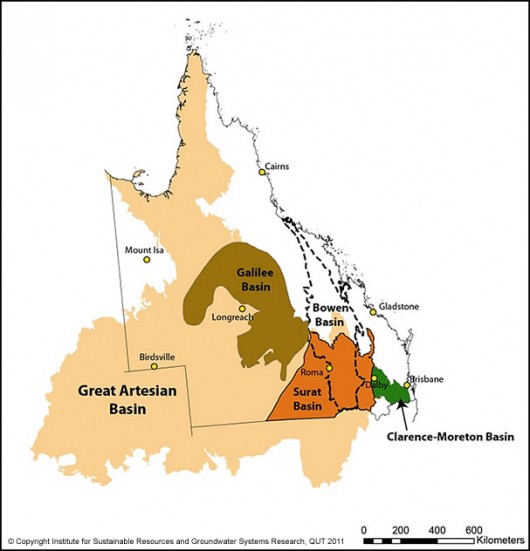

Coal Seal Gas mining permeating across Queensland food bowl

and taking water from our precious Artesian Basin Coal Seal Gas mining permeating across Queensland food bowl

and taking water from our precious Artesian Basin

.

Geoscience Australia:

.

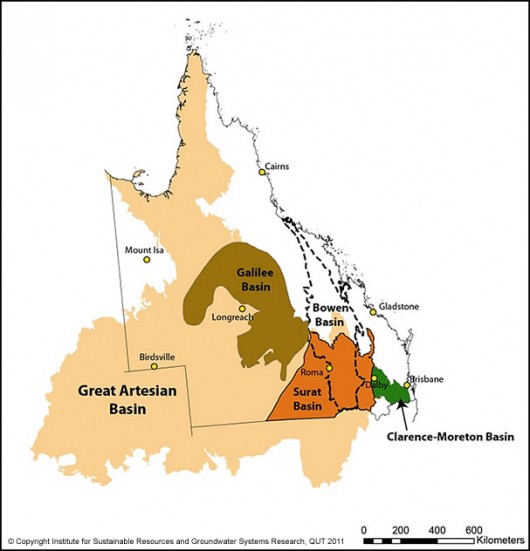

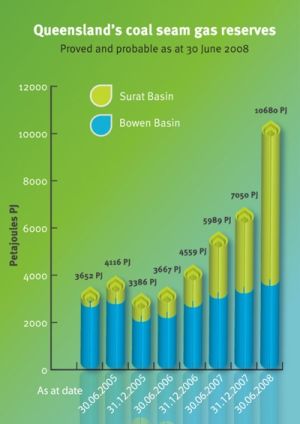

‘Coal Seam Gas (CSG) is a naturally occurring methane gas found in most coal seams and is similar to conventional natural gas. In Australia the commercial production of CSG commenced in 1996 in the Bowen Basin, Queensland. Since then production has increased rapidly, particularly during the first decade of the 21st century. CSG has now become an integral part of the gas industry in eastern Australia, particularly in Queensland.

Information about reserves of CSG has grown significantly, particularly in the Bowen and Surat basins in Queensland. In New South Wales reserves have been proven in the Sydney, Gunnedah, Clarence-Moreton and Gloucester basins. Exploration has been undertaken or is planned to be undertaken in other coal basins including the Galilee, Arckaringa, Perth and Pedirka basins.

A major driver for the growth in CSG was a decision in 2000 by the Queensland Government that required 13% of all power supplied to the state electricity grid to be generated by gas by 2005. That requirement has been increased to 15% by 2010 and 18% by 2020.

CSG reserves have grown to such an extent that a number of Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) plants have been proposed based on exports from Gladstone, Queensland.’

[Source: Geoscience Australia, ^http://www.ga.gov.au/energy/petroleum-resources/coal-seam-gas.html]

.

The grossly financial wasteful Labor Government in Queensland has become so desperate for new revenue that the promised millions in CGS royalties from this new LNG industry is tantalisingly irresistable to the extent that Queensland farms and environment have become deliberately ignored and railroaded by the Bligh Labor Government.

Bligh’s Labor Government has wasted:

- $2 billion on the Toowoomba water recycling plant, now a white elephant

- $1.1 billion on another rusting desalination plant at Tugun

- $600 million on the failed Traveston Dam plan

- $450 million on the Traveston Crossing plan

- $350 million on Wyaralong Dam, not even connected to the grid

- $283.5 million on the health payroill debacle

- $112 million on Smart Card drivers licenses that aren’t smart

- $7 million a month in government advertising

- $450,000 rental bill for an empty State Government office in Los Angeles

.

[Ed: This is criminally negligent misappropriation of the entrusted Queensland Treasury]

[Source: ^http://www.stoplaborwaste.com/]

.

Goodna Sewage Pump Station (outer Brisbane)

designed to convert to drinking water to Toowoomba

..except Toowoomba residents won’t take city shit Goodna Sewage Pump Station (outer Brisbane)

designed to convert to drinking water to Toowoomba

..except Toowoomba residents won’t take city shit

.

So with $5 billion in Queenslander taxes squandered by Queensland Labor, no wonder the Bligh Labor Government has been so desperate for the lure of mining royalties.. at any cost including jeopardising the prime agricultural land of the Darling Downs.

The development of energy resources in the Surat Basin (Darling Downs and South West Queensland region) and associated LNG projects in the Gladstone (Fitzroy and Central West Queensland) region is set provide annual royalty returns of over $850 million to the Bligh Labor Government. Bligh is more than happy to send in the corporate miners to undermine the food bowl of Queenslanders and pollute their drinking water by fracking in the process.

As the above LNG Blueprint disloses above, it is all about ” greater export revenue and royalty payments.”…at any cost – social, heritage, environmental. Queensland Labor Premier Anna Bligh has prrepared to take on the Federal Government over any increase to red tape from its new oversight of the coal seam gas industry.

[Source: ‘Queensland Premier Anna Bligh offers coal seam gas industry help on red tape’, by John McCarthy, The Courier-Mail, 20111123, ^http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/bligh-offers-csg-help/story-e6freon6-1226203063565]

.

Bligh – new CSG cash royalties

.. fracking Queensland in the process Bligh – new CSG cash royalties

.. fracking Queensland in the process

.

Federal Labor’s Environment Minister Tony Mr Burke has said that Queensland farmers are safeguarded by federal regulations that went much further than those of Queensland.

But in November 2011, confidential advice obtained by The Australian newspaper under Freedom of Information laws, shows that Tony Burke has known about coal-seam gas developments in southern Queensland have serious uncertainties about the impact on groundwater and salinity.

The documents include departmental briefings for Mr Burke’s decision to approve the APLNG project, a joint venture between Origin and Conoco Phillips that involves 10,000 production wells and more than 10,000km of access roads and pipelines.

It is the biggest CSG project ever approved in Australia.

Tara (west of Dalby), south east Queensland

Coal Seam Gas pipelines now dominate the rural landscape

Tara (west of Dalby), south east Queensland

Coal Seam Gas pipelines now dominate the rural landscape

.

On the groundwater impact, the advice says Geoscience Australia warned of “high levels of uncertainty in the predicted impacts of CSG developments on groundwater behaviour and on EPBC (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act) listed ecological communities”. It says that Geoscience Australia believed that “APLNG’s modelling requires further work to fully establish uncertainties”.

The advice to Mr Burke provided in February recommended he approve the $35 billion project because he had approved two smaller projects. This indicates the department has ignored the cumulative effects of these projects on groundwater and water use.

[Read More: ‘Tony Burke warned of ‘uncertain’ gas impact on groundwater‘, by Paul Cleary, The Australian, 20111107, ^http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/burke-warned-of-uncertain-gas-impact/story-fn59niix-1226187080366]

.

Bligh’s Labor Mates in Canberra

.

14th March, 2012:

‘Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke (Ed: Labor Party) has removed a possible electoral problem for the Bligh government in Queensland by delaying environmental approval for the massive expansion of the Abbot Point coal terminal in north Queensland until well after the election.

The Queensland government plans to expand Abbot Point, near Bowen and directly beside the Great Barrier Reef, from its current capacity of 50 million tonnes of coal a year to 400 million tonnes, but the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the expansion needs to be approved by the federal government first. The EIS was lodged in December and there is a statutory requirement for the federal minister to respond within 40 working days.

Last week, Mr Burke quietly slipped through an extension of the timeframe until the end of this year, although a hand-written note on the briefing paper written by him states that “I note the decision may still be made earlier than the extended deadline”.

The expansion of Abbot Point is particularly sensitive as the port is right beside the Great Barrier Reef. It is designed to cater for the new coalmining area in the Galilee Basin.

Concerns about possible damage to the reef through a build-up of coal ships passing through the reef have been highlighted in recent days by a visit from UNESCO officers.

Mr Burke’s decision will delay the construction of 12 coal-loading berths at the terminal that have been allocated to six companies, including Waratah Coal, owned by billionaire Clive Palmer.’

.

[Read More: ‘Sensitive Reef coal port decision off agenda‘, by Andrew Fraser, The Australian, 20120314, ^http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/elections/sensitive-reef-coal-port-decision-off-agenda/story-fnbsqt8f-1226298622984]

.

Coal Seam Gas kills American cattle

.

Meanwhile, exposure to coal seam gas drilling operations in the United States has been strongly linked to serious health problems in humans, pets, livestock and other animals, a new US study has found. Australian environmentalists say the study shows the need for caution in opening the country up to coal seam gas extraction.

University of Massachusetts researchers interviewed 24 US farmers affected by shale gas drilling and found the practice was “strongly implicated” in serious health problems in humans and animals. In one case, 17 cows died in one hour from respiratory failure after shale gas fracking fluids were accidentally released into an adjacent paddock.

Fracking refers to the controversial method of injecting chemicals, water and sand at high pressures to crack rock and release gas.

On another farm, 70 of 140 cattle exposed to wastewater from fracking died, as did a number of cats and dogs from a neighbourhood where wastewater was spread on roads as a method of disposal.

The study also cites a case in which a child was hospitalised with arsenic poisoning soon after drilling and fracking began near their home. Occupants of another home near gas wells suffered headaches, nosebleeds and rashes, and their hearing and sense of smell was affected.

The study’s authors recommend more research into the effects of shale gas extraction in the US, or a total ban on the practice.

NSW Greens MP Jeremy Buckingham says the study shows the need for caution in the expansion of CSG mining in the state.

“Many of the methods, chemicals and techniques used in US conventional and unconventional gas extraction are the same as those used in Australia with coal seam gas,” he said in a statement.

The National Toxics Network called on Australia’s state governments to conduct a full assessment of the impacts of CSG on animals living close to gas wells.

“We know so little about the long term impacts on the health of wildlife and farm animals of this industry,” the network’s senior adviser Mariann Lloyd-Smith said in a statement.

.

[Source: ‘Study warns of CSG health risks‘, AAP, The West Australian, 20120110,^http://au.news.yahoo.com/thewest/business/a/-/business/12542344/study-warns-of-csg-health-risks/]

.

‘Centralia’, Pennsylvania (USA) and its 1000 residents the victims of a coal seam mine fire in 1962,which has been burning under the area ever since.

The entire town was condemned in 1992 and only a few stragglers are left behind. ‘Centralia’, Pennsylvania (USA) and its 1000 residents the victims of a coal seam mine fire in 1962,which has been burning under the area ever since.

The entire town was condemned in 1992 and only a few stragglers are left behind.

.

Coal Seam Gas poisons cattle in Pennsylvania

.

‘Stillborn and deformed cows, ponds that turned black and poisoned drinking water. Those are some of the little-reported effects being visited on Pennsylvania in the rush to tap natural gas from the Marcellus Shale, two angry Washington County farmers told about 100 people at a forum in Lancaster city Sunday afternoon.

“This has been nothing but hell for my family and neighbors,” said Ron Gulla, whose farm near Hickory was the second Marcellus Shale well drilled in the state….’

.

[Read More: ‘2 farmers assail gas drillers at forum‘, 20110515, LancasterOnline.com, ^http://coalseamgasnews.org/2011/2-farmers-assail-gas-drillers-at-forum/]

.

Back in Queensland, on 30th May 2011, Labor Prime Minister Julia Gillard, and Queensland Labor Premier Anna Bligh unveil the coal seam gas expansion plant at Curtis Island

‘New Gas Age’ for Queensland – enthusiastically opened by Bligh ‘New Gas Age’ for Queensland – enthusiastically opened by Bligh

Goodbye beautiful innocent Gladstone

.

‘Premier Anna Bligh and Prime Minister Julia Gillard herald the ‘new gas age’ as a liquefied natural gas (LNG) storage plant opens Curtis Island off Gladstone in central Qld.’

[Watch ABC Video: ‘Gillard, Bligh unveil coal seam gas expansion‘, ABC TV, ^http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-05-27/gillard-bligh-unveil-coal-seam-gas-expansion/2734636]

.

Three months later in August 2011, Bligh’s Queensland Government was forced to investige traces of cancer-causing Benzene, toluene and xylene at Arrow Energy’s 14 CSG bores at Tipton West and Daandine gas fields near Dalby.

Benzene, toluene, ethylene and xylene (commonly known as BTEX) were outlawed last October in Queensland for use in fracking, a process used in the CSG industry to split rock seams and extract methane.

.

[Source: ‘Carcinogens found in water at coal seam gas site‘, by Kym Agius, 20110829, ^http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/queensland/carcinogens-found-in-water-at-coal-seam-gas-site-20110829-1jgxb.html]

.

Queensland Conservation Community (QCC) on Coal Seam Gas

.

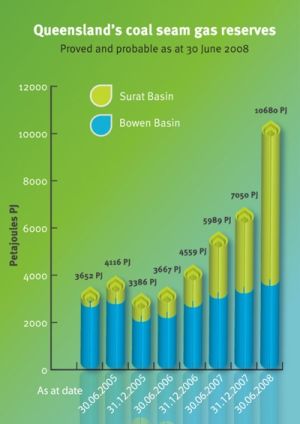

Expansion of the QLD Coal Seam Gas (CSG) industry has been occurring at a very rapid rate over recent years.

While the CSG industry is bringing wealth and jobs to areas like the Surat Basin, the immediate and longterm environmental impacts potentially caused by the industry are largely unmeasured and unchecked. This is mainly due to the rapid growth of the industry outstripping legislative and regulatory frameworks, resulting in an imbalance between the CSG industries, primary production and protecting the environment.

.

Key issues

.

The key environmental issues that QCC is concerned about include:

- Impacts to over and under lying aquifers

- Extraction of substantial volumes of groundwater as part of the CSG extraction process is likely to have a significant impact on over and under lying aquifers, which are connected to coal measures from where gas is extracted.

- Independent scientific assessment must determine that potential impacts to adjacent aquifers can be avoided and managed before CSG projects are approved.

.

Groundwater contamination

The quality of groundwater in coal seams is generally inferior to that in over- and underlying aquifers. There is a high risk that poorer quality coal seam water will leak into better quality aquifers from the large number of proposed gas wells and poor well management practices.

There is also a high risk of groundwater contamination caused by hydraulic fracturing, an industry process used to stimulate gas flows by using chemicals and applied at high pressures to fracture the coal seams.

.

Many of the chemicals used to fracture the coal seams are toxic and are known to affect human and environmental health.

- Independent scientific assessment must determine that inter aquifer contamination can be avoided and managed before CSG projects are approved

- Hydraulic fracturing must not occur until robust scientific assessment has demonstrated that groundwater contamination can be avoided.

.

Impacts to springs and groundwater dependent ecosystems (GDE)

The scale of potential long-term adverse environmental impacts to springs and groundwater dependent ecosystems caused by CSG extraction is largely unmeasured.

- Impacts to springs and GDE’s must be avoided. Independent scientific assessment must determine that potential impacts to springs and GDE’s can be avoided and remediated if impacts do occur.

- Protecting springs should be achieved by establishing set back distances around springs where CSG activities are prohibited.

- Using CSG water for beneficial purposes

.

While the Government has introduced regulations requiring CSG companies to treat CSG associated water to ‘fit for purpose’ standards, the potential environmental impacts that could occur from using treated CSG water for different purposes has not yet been fully assessed. The environmental impacts that could occur from using treated CSG water for beneficial purposes includes potential changes to soils chemistry, structure and biota; as well as water quality changes in waterways in areas where CSG water is used.

- CSG water used for a beneficial purpose must match the background environmental water quality conditions of areas where it is being used.

- Using waterways to distribute CSG water

CSG companies are seeking to release treated CSG water to rivers to distribute this water to areas where it will be used for beneficial purposes. As waterways in areas where CSG development is occurring are mostly ephemeral, introducing large volumes of CSG water year round to these waterways will change them from being ephemeral to permanently flowing. This will substantially alter the ecological composition and water quality of waterways, which will potentially cause significant adverse impacts to these aquatic environments. For these reasons, QCC does not support CSG water being introduced to river systems.

- CSG water should not be allowed to enter or be introduced to waterways

Disposal of salt and other contaminants

It is estimated that millions of tonnes of salt and other toxic substances will be produced from CSG operations. Under current arrangements CSG companies can hold untreated CSG water and brine effluent from reverse osmosis water treatment plants in storage ponds, and then dispose of this waste in a variety of ways.

.

Allowable disposal methods include:

- Creating useable and saleable products,

- Burying residual solid wastes on properties owned by CSG companies or

- By injecting the brine effluent into aquifers with a lesser water quality.

QCC does not support CSG companies being allowed to bury salt on their properties or injecting brine effluent underground due to the inherent environmental risks associated with these disposal methods. A more environmentally safe disposal method that QCC favours is to require CSG companies to rapidly dehydrate the brine effluent using waste heat generated from water treatment power plants; and then either marketing the residual solid waste or burying it in regulated hazardous substance landfill sites.

.

- Injection of brine effluent into aquifers should not be permitted

- Residual solid waste from CSG water treatment processes should only be disposed into registered hazardous substance landfill sites

- Avoiding good quality agricultural land

The CSG industry is seeking to expand into some of Queensland’s prime agricultural areas. The is likely to effect food and fibre production from impacts to groundwater resources that primary producers depend on.

Along with the impacts to groundwater, it is increasingly evident that the number of roadways, pipelines, brine storage dams and other necessary CSG infrastructure will have a significant impact on farming activities and operations.

- CSG exploration and development must be prohibited on good quality agricultural lands

.

Avoiding areas of High Ecological Significance (HES)

.

Under current legislative arrangements, the only tenure of land that is exempt from CSG exploration and development are National Parks. This means that important areas of High Ecological Significance outside of National Parks, such as wetlands, springs, biodiversity corridors and threatened ecological communities, can be degraded by CSG exploration

and development.

Although CSG companies are required to offset environmental impacts, it is unlikely that the full extent of environmental impacts caused by the expansion of the CSG industry as a whole can be effectively offset. This will result in an overall net loss of environmental values throughout the areas where CSG development occurs. That must not be allowed to occur.

.

- CSG exploration and development must be prohibited in areas of HES such as wetlands, springs, biodiversity corridors and threatened ecological communities

- Strategic re-injection of CSG water Estimates indicate that up towards 350,000Ml of groundwater per year could be extracted from coal seams as part of the gas production process.

There are significant concerns about the impacts that may occur to other aquifers that are connected to these coal seams. An effective way to mitigate impacts to over- and underlying aquifers is by strategically re-injecting treated CSG water either back into coal seams or into effected adjacent aquifers.

- Treated CSG water should be re-injected back into coal seams from where it has been extracted or into adjacent aquifers that have been affected by CSG operations

- Moratorium on CSG development

Many of the environmental issues associated with the CSG industry have yet to be satisfactorily addressed. QCC believes that a precautionary approach is needed and is calling for a moratorium to be placed on CSG projects until robust scientific assessment has determined that environmental impacts occurring from CSG operations can be avoided, mitigated and the industry can be managed sustainably.

.

- moratorium should be placed on CSG development until scientific assessment can demonstrate that environmental impacts can be avoided and mitigated

.

[Source: Queensland Conservation Community (QCC), 20101001, ^http://qccqld.org.au/docs/Campaigns/SaveWater/CSG%20Position%20Paper.pdf, >Read Paper 160 kb]

.

Threats by Coal Seam Gas to Australia’s Artesian Basin

.

‘The Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association acknowledge that CSG extraction has potential to deplete or contaminate local aquifers.

There are many of these in the northern Illawarra that recharge streams, creeks, lakes and dams in the water catchments and coastal plain.

The National Water Commission estimate that the Australian CSG industry will extract around 7,500 gigalitres (GL) of produced water from ground water systems over the next 25 years. To put this in perspective, that’s more than 13 times the capacity of Sydney Harbour. They also note that the potential impacts of CSG development on water systems, particularly the cumulative effects of multiple projects, are not well understood….’

.

[Source: ^http://stop-csg-illawarra.org/csg-risks/threats-to-water/]

.

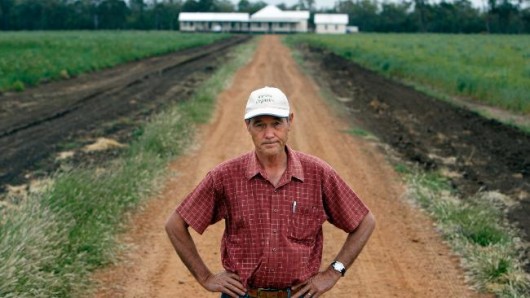

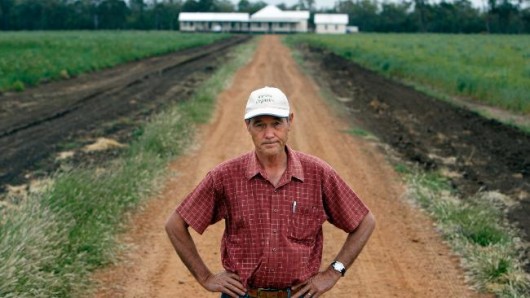

The coal seam gas industry is facing a rural revolt, with farmers threatening to risk arrest and lock their gates to drilling companies.

Organic farmer, Graham Back, at his property west of Dalby, southern Queensland

He won’t be rolling out the red carpet for drilling companies

[Photo: Cathy Finch Source: The Courier-Mail]

[Read article] Organic farmer, Graham Back, at his property west of Dalby, southern Queensland

He won’t be rolling out the red carpet for drilling companies

[Photo: Cathy Finch Source: The Courier-Mail]

[Read article]

.

Bligh’s gas infatuation is killing Gladstone Harbour

.

Aerial views show Gladstone Harbour before and after dredging operations began. Aerial views show Gladstone Harbour before and after dredging operations began.

.

An independent report on Gladstone Harbour is scathing of State Government efforts to discover what is causing major disease problems.

The interim report by fisheries veterinarian and Sydney University lecturer Matt Landos says the Government has failed to adequately monitor animal mortality and used untrained observers despite evidence of a crisis.

Dr Landos says the Government has underestimated turtle deaths, made no baseline study of aquatic animal health before the harbour’s 46 million cubic metre dredging began, made no assessment of acoustic impacts and has not investigated dying coral.

The damning report was paid for by the Gladstone Fishing Research Fund with capital sought from public donations and fishermen.

The port is undergoing major expansion, mostly for the liquefied natural gas industry.

The LNG industrial invasion of Gladstone’s Reef World Heritage Harbour

..when political gas royalties outweigh Queensland Nature

This will be Bligh’s legacy remembered, not her ‘we are Queenslanders’ spiel. The LNG industrial invasion of Gladstone’s Reef World Heritage Harbour

..when political gas royalties outweigh Queensland Nature

This will be Bligh’s legacy remembered, not her ‘we are Queenslanders’ spiel.

Labor’s mantra: ‘jobs jobs jobs’ – while buggering Australia’s environment and local workers,

because Labor jobs mean foreign 457 jobs,

where Labor selfishly reaps industrial exploitation royalties as if it were a foreign power.

Labor is buggering Queensland’s precious Barrier Reef like it is buggering Queenslanders…all for coal seam gas royalties

Why did old Captain Bligh have a cruel reputation?

. Labor’s mantra: ‘jobs jobs jobs’ – while buggering Australia’s environment and local workers,

because Labor jobs mean foreign 457 jobs,

where Labor selfishly reaps industrial exploitation royalties as if it were a foreign power.

Labor is buggering Queensland’s precious Barrier Reef like it is buggering Queenslanders…all for coal seam gas royalties

Why did old Captain Bligh have a cruel reputation?

.

Where is Bligh’s empathy for Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef World Heritage? Where is Bligh’s empathy for Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef World Heritage?

.

Former Queensland Seafood Industry Association president Michael Gardner, who helped organise funding, said yesterday that Dr Landos’ findings were at odds with the Government and Gladstone Ports Corporation view, which was that disease was related more to last year’s wet season than dredging.

46 million cubic metre dredging of Gladstone Harbour for Coals Seam Gas

Killing dugongs, sea turtles and Reef marine life in the process 46 million cubic metre dredging of Gladstone Harbour for Coals Seam Gas

Killing dugongs, sea turtles and Reef marine life in the process

.

Environment Department director-general Jim Reeves said it was incorrect that studies had not been done to assess the impact of dredging. He said Fisheries Queensland had been conducting an extensive fish health survey since August last year and studies were continuing.

The department had monitored Curtis Island turtle populations for decades before dredging began and there was no evidence of turtle deaths being underestimated. All fisheries observers were trained scientists and surveys were conducted in April and June.

. .

Gladstone now has ‘Exploding Eye’ Barramundi

..thanks Anna Gladstone now has ‘Exploding Eye’ Barramundi

..thanks Anna

.

“So far all we have seen from the Bligh government is flawed water quality monitoring, constant assertions that the problems of marine species’ deaths and fish disease have nothing to do with developments in the harbour and the desire to see developments proceed at breakneck speed.”

“The Gladstone Port Corporation’s dredging program is one of the biggest in our history and we need to know if dredging up historic layers of industrial pollutants as well as the acid sulphate soils that are known to be in the area are linked with this catastrophe.”

.

Derec Davies, a Friends of the Earth campaigner

[Source: ^http://indymedia.org.au/2011/11/09/how-to-use-a-bikelock-to-save-the-great-barrier-reef-protest-halts-gladstone-dredging] Derec Davies, a Friends of the Earth campaigner

[Source: ^http://indymedia.org.au/2011/11/09/how-to-use-a-bikelock-to-save-the-great-barrier-reef-protest-halts-gladstone-dredging]

.

Analysis showed water quality was consistent with historical trends, apart from the impacts of the January 2011 floods.

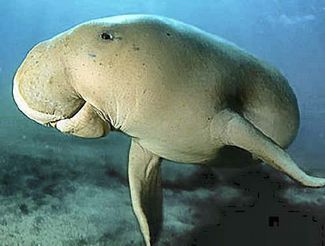

“There is no crisis for the green turtles and dugong that inhabit the area,” Mr Reeves said.

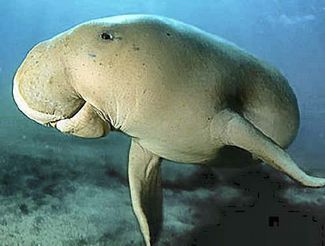

Australia’s Dugong

A native Queenslander with Existence Rights

has called Gladstone Harbour and its sea grasses home for generations Australia’s Dugong

A native Queenslander with Existence Rights

has called Gladstone Harbour and its sea grasses home for generations

.

Dr Landos said he and Dr Ben Diggles had made preliminary observations of fish health, including barramundi.

“In simple terms, all the barramundi captured were quite sick,” he said. “The vast majority, even those with no apparent external skin abnormalities, displayed tucked up abdomens and all were lethargic when handled. I would not recommend human consumption.”

Dr Landos said that despite the fish having no feed in the gut, there were ample baitfish around upon which they could feed. Mullet sampled did not show any external signs of disease. A population of 27 queenfish were sampled near the dredge spoil dumping ground. All had skin organism infestations and 18 had skin redness.

“My findings … would suggest that the 2010 flood is unlikely to be involved in their causation,” Dr Landos said.

At Friends Point in the inner harbour, 17 of 76 crabs sampled had mild to severe shell changes. At Colosseum Inlet, south of the harbour, 12 of 33 crabs showed signs of lesions. Other problems included mangrove dieback, low fish numbers and few signs of juvenile animals. A final report is expected in one to two months.

.

[Source: ‘Dredging-report-blasts-authorities‘, The Courier-Mail, ^http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/dredging-report-blasts-authorities/story-e6freoof-1226297658256]

.

A dead Dugong

– a dead Queenslander in Gladstone Harbour A dead Dugong

– a dead Queenslander in Gladstone Harbour

.

The ABC TV Four Corners current affairs Program 8th November 2011 aired an in depth report on port developments in Queensland and their impact on The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and World Heritage Area.

Watch: ABC Four Corners programme, by Marian Wilkinson and Clay Hichens: Great Barrier Grief

.

Tags: 46 million cubic metre dredging, Anna Bligh, Anna Bligh poisoning Queenslanders, Artesian Basin, BTEX, Coal Seam Gas, Dugong, Federal Environment Minister Tony Burke, Gladstone Fishing Research Fund, Gladstone Harbour, Goodna, Great Barrier Reef, High Ecological Significance, Liquified Natural Gas, LNG, Queensland Labor, Queenslanders, Toowoomba, Waratah Coal, World Heritage

Posted in Threats from Mining | No Comments »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Friday, March 16th, 2012

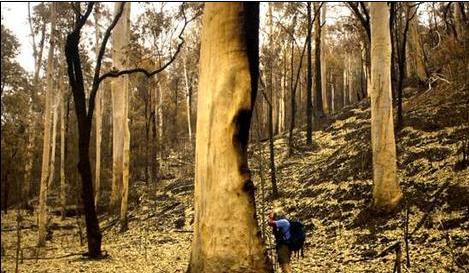

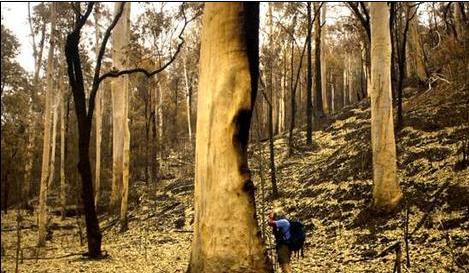

In November 2006, two separate bushfires that were allowed to burn out of control for a week as well extensive deliberate backburning, ended up causing some 14,070 hectares of the Blue Mountains National Park to be burnt.

This wiped out a significant area of the Grose Valley and burnt through the iconic Blue Gum Forest in the upper Blue Mountains of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA).

In the mind of Rural Fire Service (RFS) and the National Parks and Wildlife Service of New South Wales (NPWS), National Parks and World Heritage do not figure as a natural asset worth protecting from bushfire, but rather as an expendable liability, a ‘fuel’ hazard, when it comes to bushfire fighting.

.

This massive firestorm has since been branded the ‘Grose Valley Fires of 2006‘.

To learn more about the background to this bushfire read article: >’2006 Grose Valley Fires – any lessons learnt?‘

Pyrocumulous ‘carbon’ smoke cloud

above the firestorm engulfing the Grose Valley 20061123 Pyrocumulous ‘carbon’ smoke cloud

above the firestorm engulfing the Grose Valley 20061123

.