Author Archive

Tuesday, October 26th, 2021

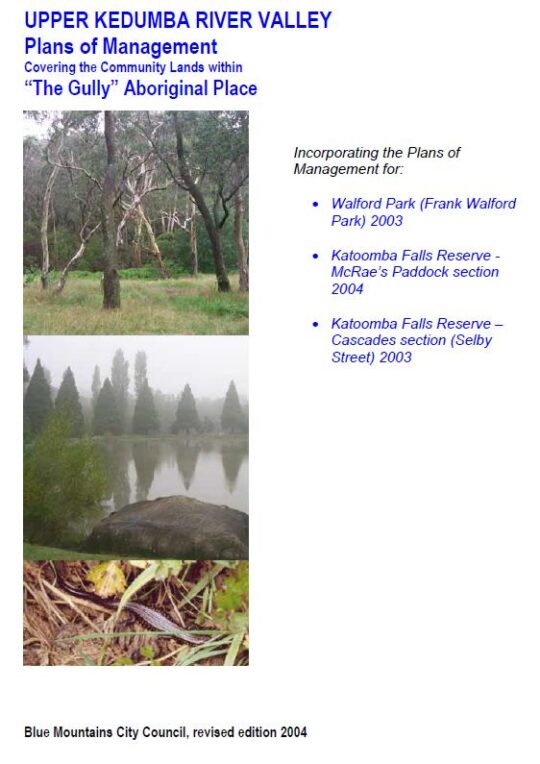

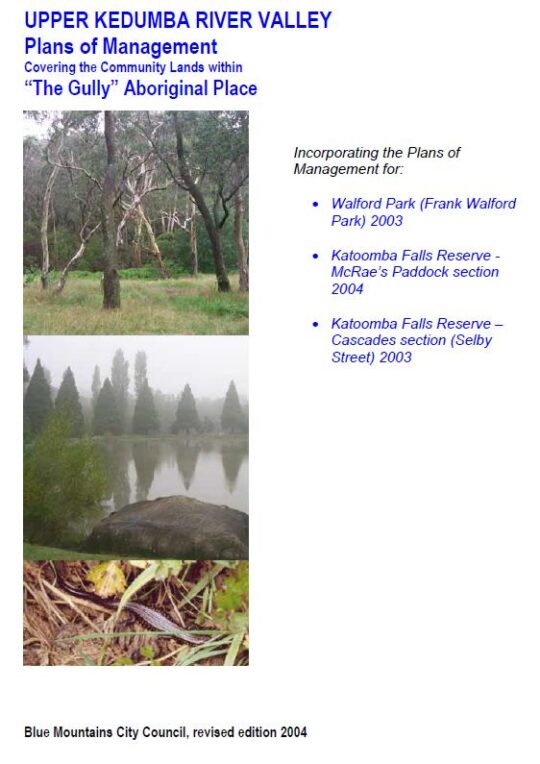

Back in 2004, Blue Mountains {city} Council’s pre-existing Plan of Management for The Gully, was entitled ‘UPPER KEDUMBA RIVER VALLEY Plans of Management Covering the Community Lands within “The Gully” Aboriginal Place‘.

Yes, sixteen words made the title a tad lengthy, so Council bureaucracy abbreviated it to ‘PoM’. Perhaps ‘The Gully Plan of Management 2004’ would have been just fine for most.

Our research attests that the 2004 Plan for The Gully sadly is but the 18th report over many decades for this long abused and neglected small valley on the western fringe of Katoomba, increasing surrounded and encroached by profitable housing development.

Council’s 2004 Plan for The Gully was some 105 pages incorporating Council’s defined ‘Community (public) Land’ reserves of the following multiple bushland parcels :

- Frank Walford Park

- McRae’s Paddock

- Selby Street Reserve

- Katoomba Falls Reserve

- Katoomba Cascades

- Plus side watercourse/riperian gullies through Council’s recategorised as ‘Operational Land’ and sold off for profit, namely Katoomba Golf Course and the significant side valley innocuously identified as 21 Stuarts Road, Katoomba…

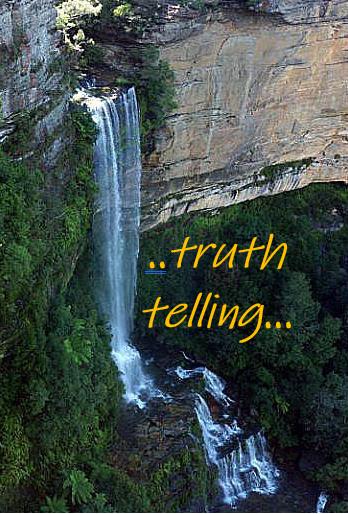

All these lands lie directly upstream and feed downstream into Katoomba Falls and the Kedumba River water catchment. The 2004 Plan was portrayed as holistically recognise, encompass and include the catchment value of entire remnant natural bushland valley upstream of Katoomba Falls (image below). It was Council’s pretense.

Katoomba Falls Katoomba Falls

Yet of the many ‘Management Policies’, ‘Masterplans’ and ‘Action Plans’ that were specified in the 2004 Plan (of Management) over last 17 years Council’s management bureacracy has done precious little by way of implementation of any ‘management’.

Many of the same bureaucrats involved with The Gully on Council over the years are still there, with increasing remuneration. Whereas the bulk of funding for remedial works undertaken in The Gully has come from external NSW government grant sources and in most cases the works undertaken by local community volunteers unpaid.

The 2004 Plan of Management for The Gully was basically filed by Council on the day Council approved the plan. Council bureaucracy has sat back let others source any funding and conduct reparations. Recent history confirms after seventeen years that Council was disingenuous about the 2004 Plan and never intended it to be a plan of management, rather just another compliance report for filing, something Blue Mountain Council has proven adept at, paying fortunes to external consultants.

All the while The Gully is but a ten minute walking distance from Blue Mountains Council chambers situated 300 metres away just across the highway. In Council’s list of management priorities, The Gully may as well be situated in another local government area.

Indeed, Council’s custodial responsibility has been perpetually avoided ever since 1957 and prior. Council’s management performance in The Gully and its broader community of support has been characterised environmentally as one of destruction and neglect, and socially as one of contempt, obstruction, hauty recalcitrance, and divide and conquer politics. From this author’s experiences since 2001, Council’s management bureaucracy has persisted with a culture of contempt for The Gully, and no councillor has dared champion the plight of The Gully’s neglected cause.

Blue Mountains Council since 1957 has held custodial responsibility for community owned lands known as Catalina Park, Frank Walford Park, then Katoomba Falls Creek Valley and then Upper Kedumba River Valley, all currently referred to collectively as ‘The Gully‘. The Gully was declared an ‘Aboriginal Place’ in 2002 under Section 84 of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974.

But Council is selective about what it labels as ‘The Gully’. Council’s zoned ‘Community Land’ (mostly stilll natural bushland) is a larger parcel that what it identiifies as ‘The Gully Aboriginal Place’ within the entire valley. You see the holistic natural valley of The Gully extends to the entire water catchment upstream, of Katoomba Falls – basically from the watershed of the Great Western Highway along the northern boundary, the watershed of Narrowneck Road along the western boundary, and what is Parke Street along the eastern boundary. Of course, this valley has been long developed by housing subdvision over the decades since colonial settlement in the 1870s and so the natural bushland and riparians zones have been bulldozed for settlement use on the bushland edge of the town of Katoomba.

So the lands that comprise The Gully are somewhat confusing to many. This suits Council’s management bureaucracy’s agenda to do what it wants. This author, a local since 2001 has been monitoring and researching Council’s bureaucracy ploys with The Gully and its communities since the late 1940s in the lead up to its 1957 forced evictions of poor people – black, white, brindle.

Council’s review of The Gully’s 2004 Plan is long overdue

In 2020, Council stated on its Gully Plan review webpage thus:

“This Plan of Management (PoM) is 16 years old and does not reflect the contemporary cultural values and perspectives held by the Gully community. Funding from the NSW Government, NSW Heritage Grants – Aboriginal Heritage Projects has been made available to review and update the Plan of Management for the Gully.”

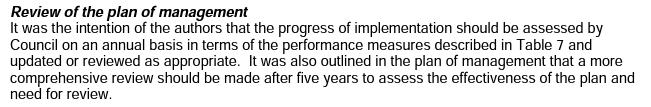

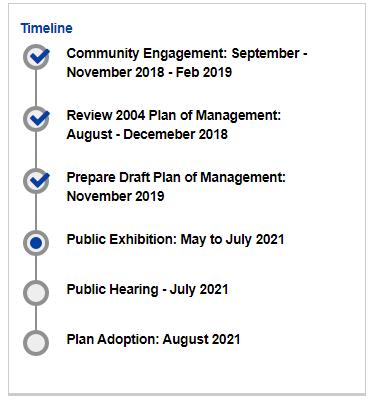

Council began its review of the 2004 plan in 2017. The bulk of the consultation process to review the 2004 Plan of Management of some 17 years prior was supposed to have be done in 2009, and with annual assessment of the progress of the implementation of Council’s approved 2004 plan, as evidenced as follows:

SOURCE: ‘UPPER KEDUMBA RIVER VALLEY Plans of Management Covering the Community Lands within “The Gully” Aboriginal Place (Blue Mountains {City?} Council, revised edition 2004, Appendix C: ‘Summary of Relevant Strategies / Policies’, p.101.

Well, better late than never. Council only undertook the plan’s review kicking and screaming in order to comply with NSW Government legislative requirements – and then it did so by outsourcing the task to a contractor and to an external consultancy using ratepayer funding. The Gully being an Aboriginal Place listed under the National Parks Act 1974, Council reviewed the 2004 Plan and prepared draft Plan of Management for The Gully, following the NSW Government’s Guideline for Developing Management Plans for declared Aboriginal Places 2012. The review of the 2004 plan was also prepared in accordance with Division 3.6 of the Crown Lands Management Act 2016. Public exhibition of the draft Plan of Management was required under Sections 38 and 40 of the Local Government Act 1993, which requires not fewer than 28 days for public exhibition of the draft plan.

So who is ‘The Gully Community‘ according to Council aficionados?

Back in the days of when dozens of concerned local residents in and around The Gully catchment were campaigning to end the invasive car racing (1989 – 2006), those considered informally part of The Gully Community were quite a bush of mixed racial/cultural background that mattered not. It was just about the cause of cariung for The Valley/Gully. It included former residents of The Gully (before the racetrack was bulldozed through the valley in 1957), both Aboriginal (mainly of Gundungurra and Dharug ancestry) and non-Aboriginal and intermarried families, descendants of those residents, subsequent locals living in and around Katoomba Falls Creek Valley, members of local community bushcare and activist group The Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Inc., and an informal collective know for a time as The Gully Guardians.

However, it is worth pointing out in the interests of transparency that Council’s definition of what it terms “the Gully Community” is unknown. It is believed to be only Aboriginal people and of those only those holding local Gundungurra ancestry and of those only a select few and mostly a select group of women of Gundungurra descent. This suits Council bureaucracy – compliant ‘Yes Folk’ to do Council bureacracy’s bidding secretively behind closed doors.

So in October 2021 just gone, following Council bureaucracy’s selective and secretive consultation process, the latest Plan of Management for The Gully has been finalised. This is plan No. 19. But worse, it’s just a plan on paper and follows a sad Council legacy of precious little actioned implementation. This latest plan has an unbudgeted pie-in-the-sky cost estimate of a whopping $4,742,910 (see summary cost table on page 113 of the 20121 Plan below in this article under ‘Further Reading’). The focus group consultants must have had their all wish lists out and fueled by a huge budget and extended timeframe. Council’s outlay for its review process of the 2004 Plan has not been made public – $250,000 perhaps or more?

The Habitat Advocate based within The Gully Catchment in Katoomba, is in possession of both the glossy printed version of the document ‘The Gully Aboriginal Place Plan of Management‘ dated 4th October 2021 of some 145 pages, as well as the digital version of the same title. The latter we provide a full copy at the end of this article under ‘Further Reading‘ publically available for free to download and print by anyone. The Gully is after all is gazetted ‘Community (public) Land’, so its plan is by extension, public, not restricted by Council’s presumptive copyrighting.

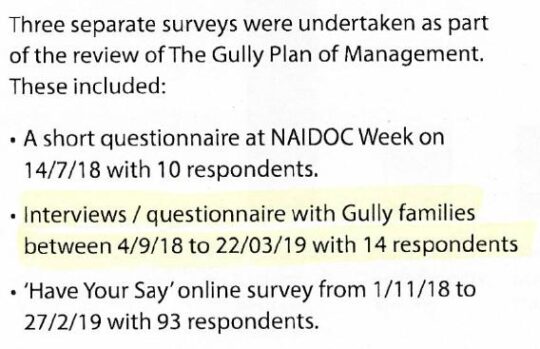

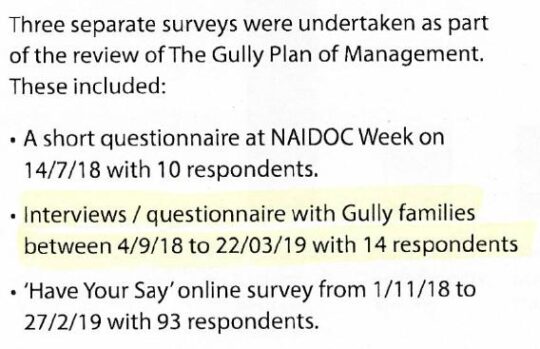

Council claims that it “consulted extensively in preparation of the Draft Plan of Management (POM), including with Gully families, at NAIDOC week, and with the broader community through an online survey over a period of four months. The public exhibition of the Draft POM is an important part of community consultation and was open for a period of 60 days, longer than is required (42 days) under the legislation (Local Government Act and Crown Lands Management Act 2016). The public exhibition period was advertised via media and advertising and closed on 26 July 2021.”

However, once again as in the past, Council’s consultation process was both selective and controlled. Council only allowed and heard what it wanted to hear.

A. Blue Mountains Council’s Selective Consultation

In this review process, Council partnered with two favoured groups, being ‘The Gully Traditional Owners Inc.‘ (membership is not publicly available) and ‘The Gully Cooperative Management Committee‘ (membership is not publicly available). It is understood that the membership make up of both groups may well be dominated by the same few select individuals. It is for Blue Mountains Council to disclosed this given that The Gully, whilst in part respected as an Aboriginal Place under the NPWS Act 1974, remains gazatted as Community (public) Lands.

B. Blue Mountains Council’s Controlled Consultation

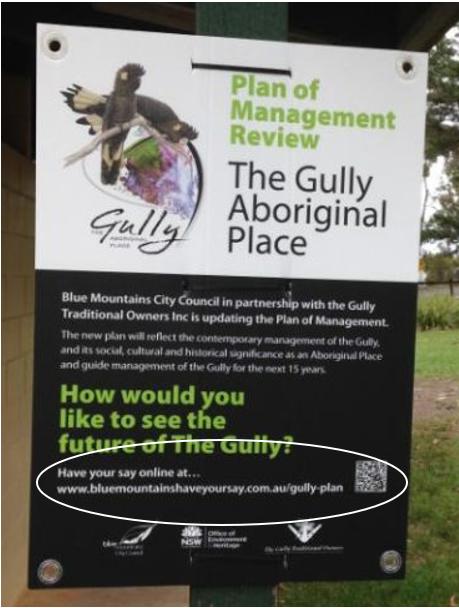

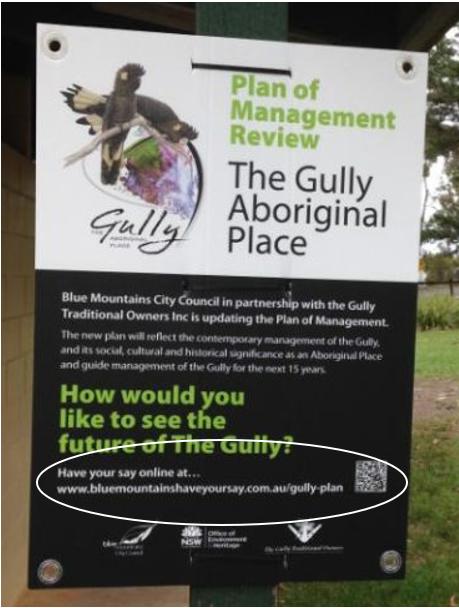

Between 2017 and 2021 Council published its review of its 2004 Plan of Management. It published a webpage on the Internet, a subdomain ^https://yoursay.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/gully-plan It ran a series of advertisements in the Blue Mountains regional Gazette newspaper and posted a number of physical signs around The Gully valley like the one below. Council termed this its Exhibition Period.

However, all contributions from locals and the broader community was funmelled by Council compulsorily to the above webpage and to be submitted to Council via an online form. In this way, Council could avoid genuine face-to-face dialogue with the interested community.

NOTE: ‘Have Your Say’ is simply outsourced software that is designed for community engagement, so that Council management and staff don’t have to. ‘Engagement Hub’ is one such software product.

And remember that the NSW Government pandemic lockdown which outlawed normal human face-to face conversation had not taken effect until March 2020. In this way, Council sought to deliberately avoid genuine and open community exchange and conversation on The Gully and of Council’s intentions for The Gully. Such aloof and tokenistic ‘community consultation’ by Council bureaucracy sadly has become the norm by what ought to be local council in power to representative oof local community interests and values.

Council claims that it has undertaken comprehensive “stakeholder engagement” as part ensuring community participation in the preparation of Plans of Management for this community land known as The Gully. However, Council’s communications and engagement was restricted to “Aboriginal families of former Gully residents and their descendants, NAIDOC Week participants in The Gully (2018), and to people who visit and use The Gully through the Have Your Say survey. The latter was an online form for one way input, not dialogue, and not a forum.

Instead of Council reviewing the 2004 and its implementation or otherwise, Council ignored the 2004 Plan and instead focused on the view of stakeholders on:

- What’s important?

- What needs to be protected?

- How should be The Gully be in the future?

Council bureaucracy’s planning framework and scope for reviewing the 2004 Plan was conveniently restricted to its formal relationship with The Gully Traditional Owners Inc. and within The Gully Cooperative Management Agreement.

According to Council’s Gully Plan webpage “decisions on whether a suggestion can be included in the Plan of Management (for 2021) is measured against the core cultural values of The Gully as an Aboriginal Place, and whether the ideas are supportive of these core values. The outcome of this consultation is presented in Chapter 5 of the Draft Plan of Management Talking with the Community. A complete summary of is presented in Talking with the Community Stakeholder Engagement Report – The Gully Aboriginal Place Katoomba.”

Notably input from the broader community and non-Aboriginal ‘stakeholders’ who inputed via Council’s outsourced ‘Have Your Say’ online form and was deliberately excluded.

There was one other public forum offered by Council, its ‘Public Hearing‘ so-called staged by Council staff and management on Saturday 7th August 2021 by means of online forum via Zoom meeting software.

This public hearing had in the lead up been promoted by Council as to focus on The Gully’s Plan of Management review. Keenly, almost 70 individual members of the community enrolled to contribute to the public hearing.

However from the outset of the Zoom meeting, Council’s outsourced consultant Ms Sandy Hoy was quick to disappoint. Ms Hoy is principal director of the planning consultancy firm Parkland Planners based in Freshwater on Sydney’s northern beaches – once again Council goes off-Mountains to source its consultants.

The so-called ‘public hearing’ was distinctly an online forum NOT to discuss the plan of Management, but rather for participants to input into Council’s alternative piece of legislation – Council’s ‘ The Gully Aboriginal Place Proposed Recategorisation of Community Land July 2021‘.

So as toward the end of October 2021, with submissions received, Council declared “The Exhibition period for the Draft Plan of Management has now closed”.

Council’s final recategorisation document for 2021 was subsequently renamed thus:

This is a sneaky and mischievous Council that has form back to 1989 and indeed back to 1957 when it bulldozed Aboriginal settlements in The Gully.

So this is The Gully Plan 2021, number 19 no less – again set for filing by Council bureaucracy for another decade or so.

The Gully’s Plan of Pretense No.19. The Gully’s Plan of Pretense No.19.

And Council Propaganda on all this?

“Thank you to everyone who took the time to make a submission. All submissions will be analysed and carefully considered as part of the consultation process. Recommended amendments to the Draft Plan of Management will be conveyed to the Councillors when the Final Plan of Management is prepared for adoption. This is currently anticipated to be at the 26 October 2021 Council meeting.

SOURCE: ^https://yoursay.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/gully-plan

So contradictorily, on the one hand Council bureaucray’s public hearing staged on Saturday 7th August 2021 was promoted on its flyer to discuss and input into the 2021 Plan of Management,. But then on the day of the ‘public hearing’ up front Council’s consultant Sandy Hoy instructed all participants that this was NOT to be the focus of the hearing, but purely on some other obscure document about Council’s land recategorisation in The Gully and somehown no related to the 2021 Plan. Then on Council’s website the comment above reads ..“Thank you to everyone who took the time to make a submission. All submissions will be analysed and carefully considered as part of the consultation process. Recommended amendments to the Draft Plan of Management will be conveyed to the Councillors when the Final Plan of Management is prepared for adoption.”

How deceptively mischievous of Council’s community consultative process!

Other points noted on Council’s webpage on The Gully:

- Council’s community consultation has concluded with The Gully’s plan version dated 4th October 2021.

- The Gully Aboriginal Place PoM 2021 was endorsed at the Council meeting 26th October 2021.

- The Gully Aboriginal Place 2021 Plan of Management was formerly adopted 28 Oct 2021

- Council claims that “there are no proposals to sell off, or develop, any bushland or public land within the Gully for private housing. The Gully is comprised of Council Community land and Crown land classified as Public recreation reserve, as well as a number of Council and Crown road reserve. In regards to concerns focused on the parcels of 38-46 Gates Avenue:

- The 5 parcels of land of 38-46 Gates Avenue are not within the Gully Aboriginal Place area as Gazetted in 2002. The Gully Draft PoM has been updated to include all and only land within the Gully AP area. Hence these parcels were not included in the revised PoM.

- The Gully Draft PoM does not propose any change to the classification of Council community land within the Gully AP, (or for 38-46 Gates Avenue). Changes from Community land to Operational Land is a separate process and would require revision of the Local Environmental Plan (LEP).

- There are no proposed changes to the land classification, or land categories of the land parcels of 38-46 Gates Avenue. They remain classified at Council Community (13/1-4/L1/2059) and Operational land (13/5/L1/2059) and remain categorised Natural Area Bushland.

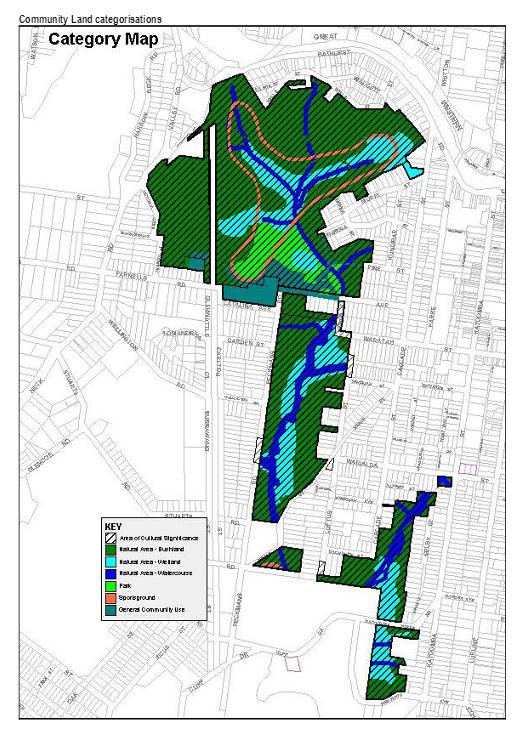

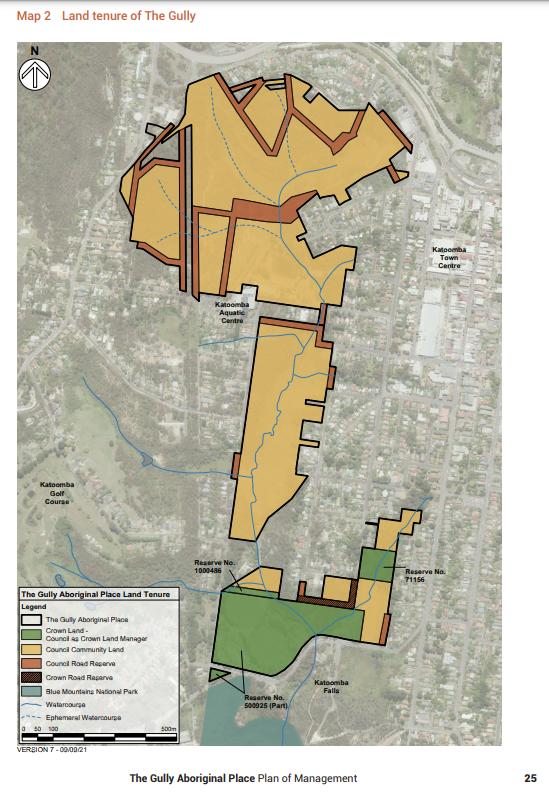

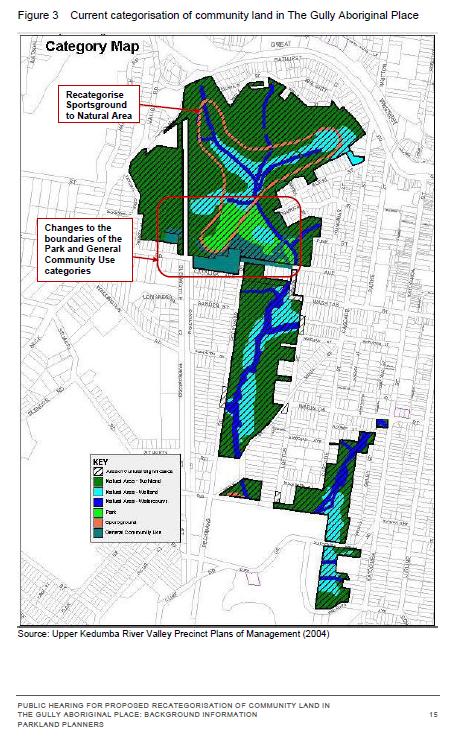

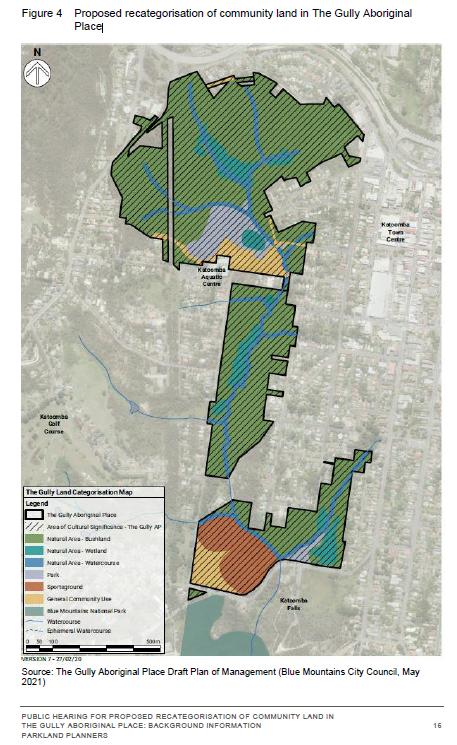

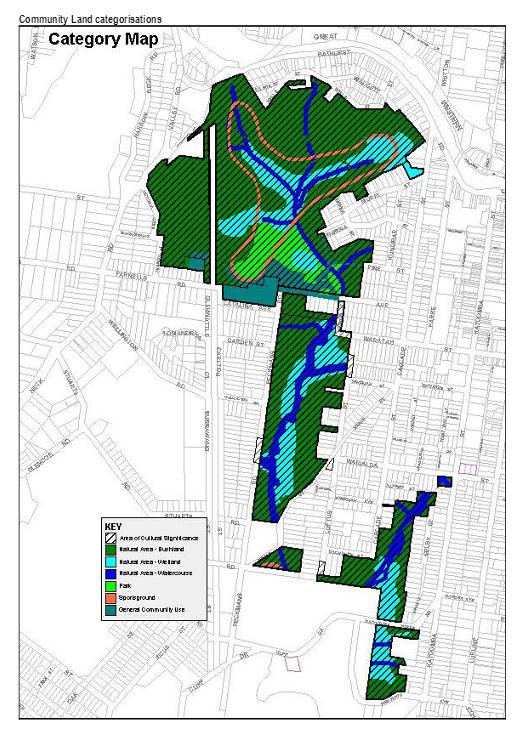

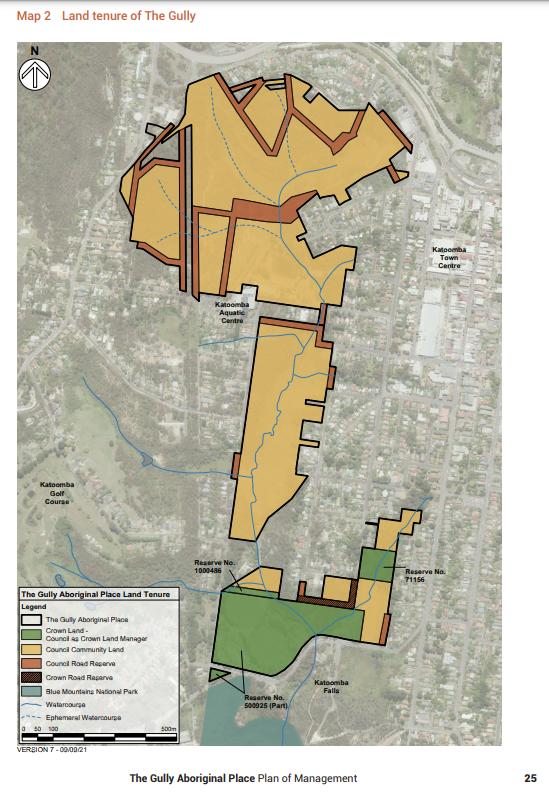

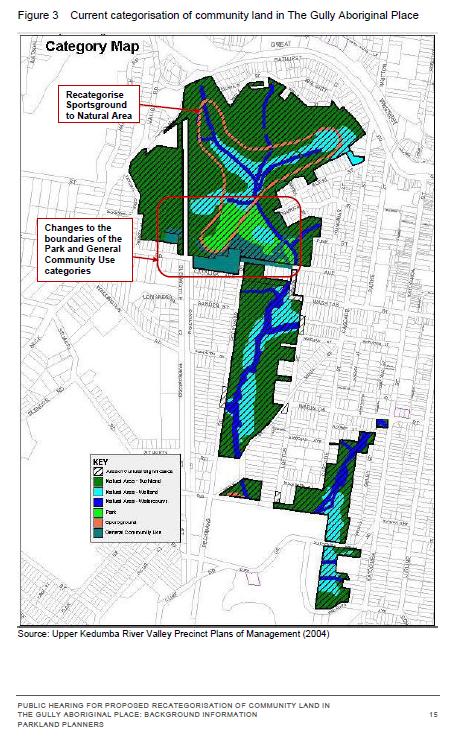

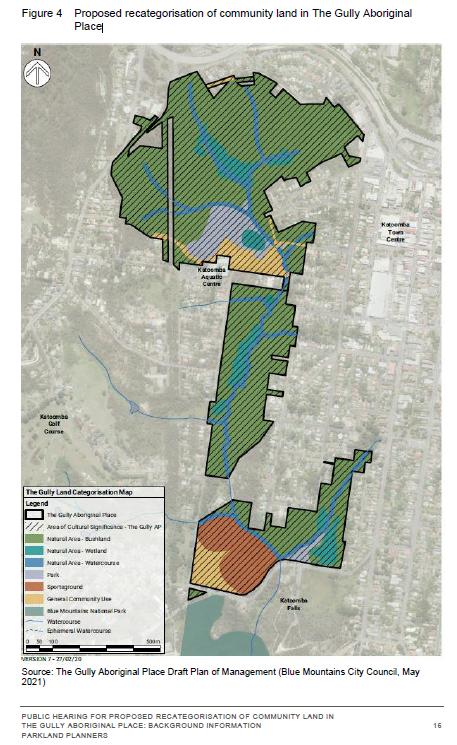

As for point 4, this is contrary to the land categorisation mapping in the 2004 Plan. Compare the following two maps of land categorisation. The first map is in the 2004 Plan on page 7. The second one is the 2021 Plan on page 25. Spot the notable differences – the many bushland parcels missing from the 2021 map, notably the 5 parcels of land of 38-46 Gates Avenue on the corer of Peckmans Road near the Aquatic Centre.

Council has form over many decades in re-categorising Community Land to Operation Land under its custodianship – Hat Hill Airstrip, Wentworth Falls Golf Course, …

Further Reading:

.

[1] The Gully Plan of Management 2021 (Final) , 4th October 2021, Blue Mountains (city) Council), ^https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/The-Gully-POM-4-Oct-2021.pdf

.

[2] Council’s Gully Plan, ^https://yoursay.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/gully-plan [Editor’s note: This outsourced webpage link is likely to be deleted by Council soon, given that its ‘consultation process’ has concluded]

.

[3] The Gully Plan of Management Report to Councillors, Item 12, 26th October 2021, ^https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/The-Gully-Plan-2021-Council-Paper.pdf

.

[4] Gully Plan for 2021 is unbelievably No. 19, ^https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/gully-plan-for-2021-is-unbelievably-no-19/

.

[5] ‘Have Your Say’ community engagement software, Engagement Hub, ^https://portal.engagementhub.com.au/

.

[6] Parkland Planners, Council’s outsourced planning consultant for its public hearing staged online on 7th August 2021, Freshwater, NSW, ^http://www.parklandplanners.com.au/about-us/people/

.

[7] The Gully Collection, ^https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/consultancy/the-gully-in-katoomba/the-gully-collection/

.

.

Wednesday, August 25th, 2021

Local residents in and around The Gully water catchment area situated on the western side of the rural township of Katoomba may be astounded by the following truths we at The Habitat Advocate have gleamed of late about Blue Mountains Council’s legacy of plans for The Gully.

An analysis by our editor into the archival records maintained by The Habitat Advocate reveals that this current report/plan by Blue Mountains Council entitled The Gully Aboriginal Place Draft Plan of Management dated 7th May 2021 is actually Plan Number 19. There could well be more out there.

Don’t believe it? Well we have a copy of almost every one of the nineteen reports, and these are just the ones we know about. This revelation comes after being a member of one of the longest lasting environmental groups in the Blue Mountains region, ‘The Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Inc.’ which lasted for 28 years initially forming informally in 1988 to protest and lobby against the Catalina Raceway from 1988 incensed by Bob Jane’s helicopter buzzing low over residents’ homes around what was then Catalina Park. Over the span of half a lifetime, The Friends fought many a campaign against a host of environmental threats to the valley/gully and amassed a considerable record of material during that period.

The following is our list of the planning reports into The Gully:

List of Plans for The Gully, so far…

- Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study A & B (date TBA)

- FWP – ‘Bushland Management and Report’, (date TBA)

- Frank Walford Park Master Plan for Development 1955 (car racetrack), by Katoomba Municipal Council

- Draft Assessment of Frank Walford Park, Katoomba – Land Suitability, Environmental Constraints, circa 1980

- Frank Walford Park Management Plan 1981, 54 pages

- Katoomba Falls Creek Valley by Neil Stuart (provided to Wentworth Falls TAFE Library on special reserve), 1988 and revised in 1991

- Katoomba Falls Reserve Draft Plan of Management, Volume 1, by Mandis Roberts Consultants for Blue Mountains City Council and the NSW Department of Lands, April 1990 (possibly a Volume 2 as well)

- Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study – Part 1 (Draft Report and Management Plan of 87 pages) and Part 2 (Technical Reports, Data and Analysis of 55 pages) by Fred Bell of F.& J. Bell and Associates Pty Ltd and Dr Val Attenbrow, June 1993

- The Gully Archaeological Grant Project, 16th August 1995

- ‘Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Draft Plan of Management – Main Report’, by Des Brady of Connell Wagner Pty Ltd, of approximately 150 pages, April 1996

- Frank Walford Park Plan of Management, December 1998

- Upper Kedumba Valley, Katoomba – Report on the cultural significance of Upper Kedumba Valley for declaration as an Aboriginal Place prepared by Dianne Johnson with Dawn Colless for NPWS, 162 pages, 3rd July 2000

- Draft Katoomba-Leura Vegetation Management Plan by Blue Mountains City Council, December 2000, 46 pages,

- Upper Kedumba River Valley Plan of Management (The Gully Aboriginal Place – Council Revised Edition, (Spiral Bound, 105 pages) by Environmental Partnership, February 2004

- Final Report for Sydney Catchment Authority – Catchment & Improvement Grant No. 44 Upper Kedumba River Vallkey, prepared by members of Kedumba Creek Bushcare 7 Blue Mountains City Council March 2005, 27 pages.

- A Heritage Study of the Gully Aboriginal Place, Katoomba, New South Wales by Allan Lance of Heritage Consulting Australia Pty Ltd August 2005 (2 versions – a detailed confidential version for the local Aboriginal peoples and a second summary version for Blue Mountains City Council, 113 pages)

- Construction Environmental Management Plan – Blue Mountains Sewer Trunk Mains Amplification: Upper Kedumba River Valley, South Katoomba Sewerage Catchment by Total Earth Care Pty Ltd for Sydney Water and Blue Mountains City Council, 17th October 2007, approximately 50 pages.

- Reconnecting to Country – Progress Report #2 by Rouse Water, Council, Gully Traditional Owners, Sustainable Futures Australia, Widjabul Custodians, September 2009. (possibly a Progress Report #1 as well)

- The Gully Aboriginal Place Draft Plan of Management 7th May 2021, by Soren Mortensen and Brad Moore, Blue Mountains City Council, 142 pages.

As Council currently prepares its final version of its 2021 plan version for The Gully, the obvious critique we posit to Council is that it is about time Council actually focuses on implementing its plans rather repeatedly spending money having more plans written.

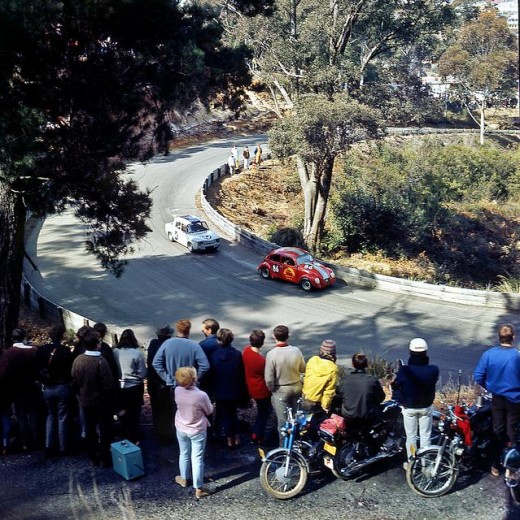

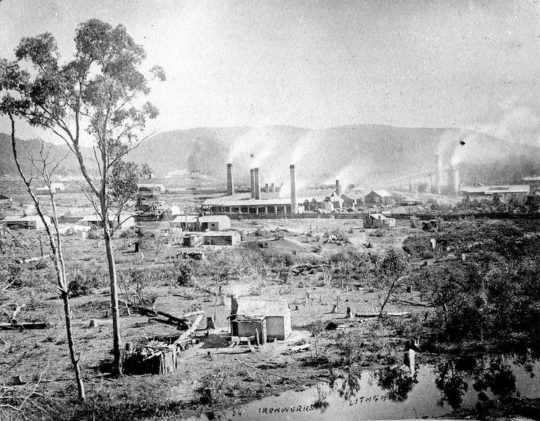

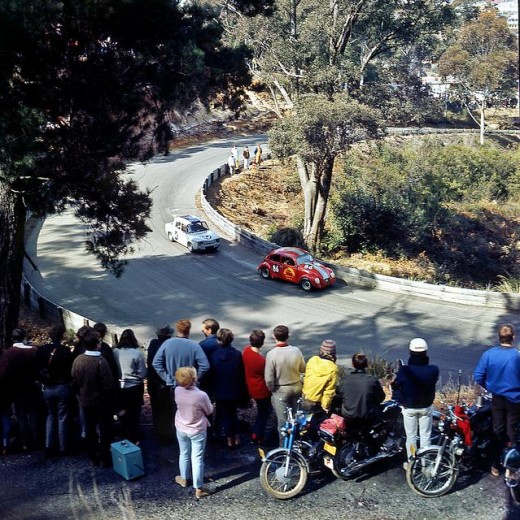

We point out that the only plan on The Gully that Council has funded out of its budget (ratepayers’ money) and not from external grants was the construction of the racetrack in 1959. And then the funding was a loan to the then Blue Mountains Sporting Drivers’ Club Ltd, a collection of wealthy local business men who persuaded Council to bulldoze the homes of the poor residents so they could race cars on a new racing circuit.

Catalina Park Raceway operated officially from 1961 to 1971 when the organisation running it, the Blue Mountains Sporting Drivers Club went into liquidation.

Council’s loan was in excess of £20,000 (say a conservative $40,000 equivalent at the time, since at the Australian government’s switch to decimal currency back in 1966 set the conversion rate of $2 to being equivalent to £1 (Australian).

[SOURCE: Minutes of Special Meeting of the Council (duly convened) , Tuesday 13th day of January 1959, page 8, Item 45, signed as validated by the Mayor and Town Clerk and verbatim thus:

“Car Racing Track – Catalina Park, Katoomba. Page A12 Town Clerk’s Report.

Resolved on the motion of Alderman K. Smith and W. Smith that consideration be given when dealing with the Loan Estimates for 1959/60 to the inclusion of an amount of about £20,000 for the construction of a blacktopped surface to the racing track and the provision of adequate safety fencing.”

In today’s value that $40 000 would be valued at about $700,000 in today’s money in 2022. That budget excludes the costs of Council’s contracted bulldozer work to demolishing The Gully homes, then grade the new racetrack circuit, or the deforestation, or the construction of the changing sheds beside the lake, or the red brick toilet block inside the track circuit, or the addition of the dirt Rallycross circuit or the other racing infrastructure.

Loan calculation (estimate only):

SOURCE: InflationTool.com website, ^https://www.inflationtool.com/australian-dollar/1959-to-present-value?amount=40000&year2=2022&frequency=yearly

That ratepayer loan by Council to the Blue Mountains Sporting Drivers’ Club Ltd was never repaid. The opportunity cost of ratepayers’ wealth for more vital needs of the Blue Mountains would have been considerable. It was an indulgence by certain councillors and their wealthy business mates and off-Mountains petrol heads to provide an exclusive hobby. It was all bugger The Gully residents and the surrounding local residents with the decades of thunderous racetrack noise in the process. Whilst the official racing ended in 1971, unofficial racing continued to 2002 when The Gully was gazetted an Aboriginal Place. But the illegal motor racing persisted for another three years until up to December 2005 – The Habitat Advocate as a local has records to support this.

Irresponsibly, council management and councillors at the time were mindful of Council’s massively over-indebtedness to the tune of £155,460 (excluding Electricity debts). Records show that Council at the time had been threatened by legal action to withdraw its claim for loan recovery. So likely due to Council’s then dire indebtedness at the time, Council cowered, backed off and wrote off racing track loan to its business mates.

Saturday, August 21st, 2021

The Gully in Katoomba – yet another vacuous draft Plan of Management by Council, 7 May 2021

A Brief Background

Back in 2004 a Plan of Management was published for The Gully in Katoomba by its government custodial owner Blue Mountains Council (Council). This followed three years of Council delegating an off-Mountains consulting firm ‘Environmental Partnership‘ (Ultimo-based) to research and draft an expensive and length report of some 105 pages.

This 2004 Plan followed a host of previous studies, reviews and reports including ‘The Bell Report’ of 1993 – its correct title being ‘Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study‘ of some 87 pages undertaken by environmental consultants F. & J. Bell and Associates Pty Ltd. This plan in 1993 had been commissioned by local Katoomba environmental activist group ‘The Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Inc.‘ (1989-2016) thanks to a $10,000 government grant which was the cost of this very details and independent study into Katoomba Falls Creek Valley, which was Council’s official name of The Gully at the time. For more information on this study please refer to the Further Reading reference section at the end of this article.

The Gully’s evolving names

Note that the term ‘The Gully‘ was first officially applied to this creek valley in Katoomba by Council in the 2004 Plan of Management. This is the 2004 Plan -was ridiculously long title of 16 words verbatim as:

‘UPPER KEDUMBA RIVER VALLEY Plans of Management Covering the Community Lands within “The Gully” Aboriginal Place’.

Put that up your jumper! Here’s the original for reading, download and printing in the public domain:

It followed That draft document was entitled, which is an affectionate term used by former residents and their descendants from the 1950s and generation prior. Other terms for The Gully have been:

- ‘Blacks Camp‘ (a colonial disparaging term [1870s up to the 1950s] as cited in the book ‘Artificial Horizon – Imagining the Blue Mountains’, p.198, by Martin Thomas, 2004) (being the northern section)

- ‘Katoomba Falls Creek Valley‘ (being the entire 70+ hectare creek valley of riparian bushland area still not yet sold off by Council for housing)

- ‘Frank Walford Park‘ (being also the northern section)

- ‘Walford Park’ (being also the northern section without Cr Walford’s first name ‘Frank’)

- ‘McRae’s (horse) Paddock‘ (being the central section)

- ‘Selby Street Reserve‘ (being the central section’s eastern side watercourse creek gully from a spring at now Hinkler Park)

- ‘Katoomba Falls Reserve Cascades section‘ (being the same central section’s eastern side watercourse creek gully from a spring at now Hinkler Park)

- ‘Catalina Park‘ (being the northern section named by Council in the late 1950s on behalf of the Blue Mountains Sporting Car Club Ltd)

- ‘Upper Kedumba River Valley‘ (being the entire creek valley as renamed by Council in 2002)

- ‘Katoomba Falls Reserve’ (being the southern section dominated by two grass ovals named by Council)

- ‘The Gully Aboriginal Place‘ (being a lesser portion of the entire 70+ hectare creek valley of riparian bushland, since many bushblocks of what as Community Land has been sold off for housing, or else rezoned or proposed for rezoning so that Council’s coffers can be boosted by land sales for more housing)

- ‘Garguree‘ is apparently a regional Gundungurra Aboriginal word meaning ‘gully’ which was purportedly provided by a local historian into Blue Mountains Aboriginal heritage Jim Smith PhD acting as a consultant to The Gully Traditional Owners (group) circa 2007.

Of note, two significant side watercourse gullies flowing into The Gully from the west are excluded from The Gully’s geographic scope by Council’s mapping.

One side watercourse flows into The Gully through a very large bushland/riparian zone side gully having a land title address of 21 Stuarts Road, Katoomba. The second to the south flows through what was clear-felled bushland/riparian zone and then bulldozed, graded and fertilized into the now defunct Katoomba Golf Course which Council had backed financially. This year the site of the old Katoomba Golf Course is being prepared by Council, external consultants again enticing two universities to develop it as believe it or not a ‘Planetary Health Leadership Centre‘ – how hypocritical on a site of ecological destruction!

Recalling the 2004 Plan of Management and its drafting, despite many efforts by locals expressing a keen desire to constructively engage with Council to provide input into this Plan, Council arrogantly shunned these requests, so very little local community consultation went into this 2004 Plan.

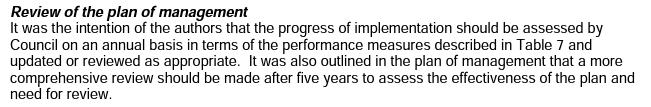

On page 101 under the sub-heading ‘Review of the plan of management‘ it reads as follows:

“It was the intention of the authors (Environmental Partnership) that the progress of implementation should be assessed by Council on an annual basis in terms of the performance measures described in Table 7 and updated or reviewed as appropriate. It was also outlined in the plan of management that a more comprehensive review should be made after five years to assess the effectiveness of the plan and need for review.”

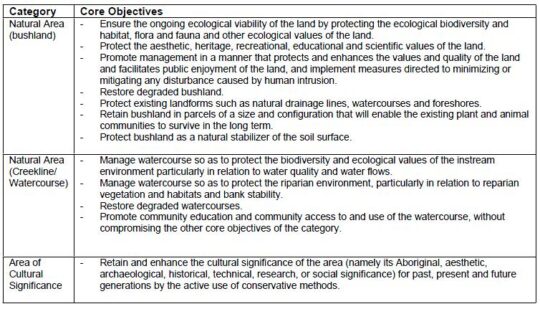

This is the Table 7:

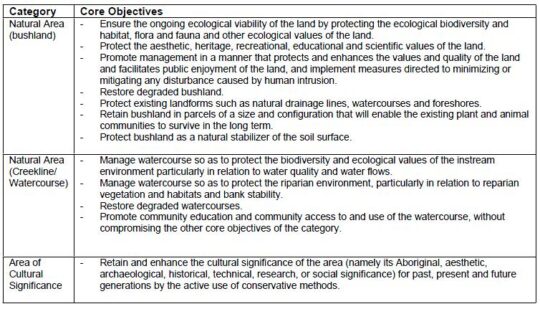

Well, neither the annual assessment of progress nor the five year review took place. None of the core objectives has been achieved by Council since 2004 (nor prior from the Bell Report of 1993) and it is now 2021.

From our experience over the past twenty years as local activists to save and protect the ecology of The Gully, Council’s ongoing neglect and abuse of The Gully has persisted and particularly Council management’s disdain for local Bushcare volunteers to altruistically request Council to commit to caring for and rehabilitating The Gully’s natural ecology after decades of harm.

It has taken until 2017 for Council to finally get around to reviewing its 2004 Plan of Management after some thirteen years, because Council was legally required to undertake a formal review of the 2004 Plan of Management – still pending in 2021…

“in accordance with the requirements of the Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) and the Crown Land Management Act 2016, and the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) Declared Aboriginal Place Guidelines for Development Management Plans.”

[SOURCE: ‘Public Hearing for the Proposed Recategorisation of Community Land in The Gully Aboriginal Place, July 2021, by Parkland Planners, Background Information, page 1, > https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Public-Hearing-for-Proposed-Recategorisation-of-Community-Land-in-The-Gully-Aboriginal-Place-July-2021.pdf]

The 2021 Plan has been prepared by Council’s contracted Environmental Planning Officer Soren Mortensen and Council’s Aboriginal Community Development Officer Brad Moore is vastly different to the 2004 plan. However a quick comparison of the 2004 Plan and the current 2012 draft Plan reveals that most of 2004 Plan’s 105 pages have been ignored in the 2012 draft plan. The current 2012 draft plan reads more like a cultural document borrowed from elsewhere and applied to The Gully instead of being as a place-based plan of management for a natural place as is the 2004 plan.

Our concerns about Council’s proposed “Re-categorisation” of ‘Community Land’ in The Gully

After 20 years experience in trying to consult with Blue Mountains Council about The Gully (respecting this valley, caring for this valley and rehabilitating the valley’s neglected and abused ecology) we have learned not to trust Council management.

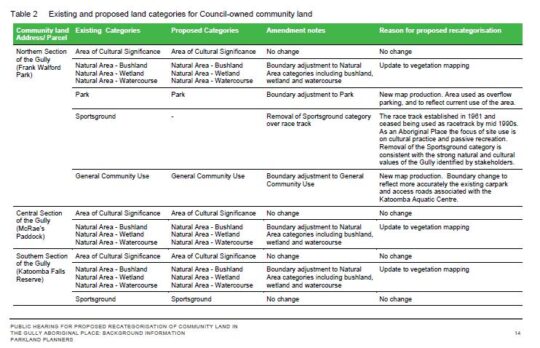

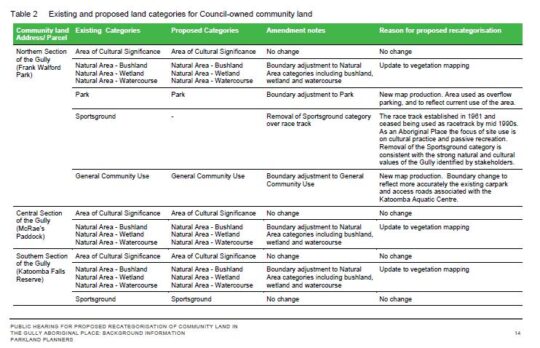

Whilst The Habitat Advocate is receptive to Council’s proposed reclassification of the current Council-owned community land specifically and only to the defunct Catalina Raceway from being a ‘Sportsground’ to being a ‘Natural Area’, this proposed reclassification is noticeably absent in the Table 2 on page 14 (copy below) of the ‘Background Information document supplied. The relevant column headed ‘Proposed Categories’ in the table is blank (“-“). Is this an oversight or intentional?

History is history, and the impost of the racetrack and motocross circuit in the northern section of The Gully back in 1957 involved Council’s forced eviction of numerous poor residents from their simple bush homes, including the violent demolition of their homes by mechanical excavators. The racetrack remnants remain since the track was ultimately shut down to vehicles permanently in 2003. We consider it is important the history of the racetrack and this traumatic story is not lost to current and future generations.

We are opposed to the remnants of the bitumen racetrack being destroyed by any excavation works, but rather the track be allowed to be significantly narrowed in width, and to be maintained to facilitate passive recreation use for following purposes:

- Recreational Walking (NOT organised running/marathon events)

- On-Leash Dog Walking (NOT off-leash and no more mass gatherings of many dogs like the RSPCA’s annual Millions Paws Walk event that invaded The Gully back in May 2004)

- Individual Cycling (NOT large groups of cyclists or organised cycling events)

- Fire Truck Emergency Access (track to a maximum width of 4 metres wide) in order to facilitate the extinguishing of a bushfire (NOT RFS bush arson/‘hazard reduction’). NB. The original racetrack width was at least 10 metres wide and has since has the natural bushland retake the invasive bitumen.

- Other Passive Uses – such as interpretation and for cultural purposes by the local Aboriginal peoples.

However, we are otherwise opposed to Council’s proposed reclassification of the Council-owned community land in The Gully because there are numerous land parcels shown in the supplied mapping on Page 16 (copy below) that indicate their removal from the current community land categorisation shown on page 15 (copy below). The fear is that this removal will result in Council’s selling the excludes land parcels for housing development and so again profiteer from The Gully as it has in the past.

We also opposed Council’s proposed reclassification because the supplied mapping scale (approx. 1:10,000) is too small a scale ratio to read and to discern the boundary changes accurately. A more readable map scale ration would be 1:5,000 and we request that Council provide this to all registered stakeholders included in:

- Council’s Stakeholder Engagement Methodology (2018-2019)

- Council’s Public Hearing for Proposed Re-categorisation of Community Land in The Gully (2021)

Council’s supplied mapping is also obscure. Whereas the supplied map for the current categorisation (Figure 3 on page 15) is cadastral (that is, shows land parcels) and is overlayed with colour-coded categorisations; the supplied map for Council’s proposed re-categorisations is an aerial photo with the colour-coding overlay in heavy bold which makes it impossible to read accurately. The comparisons between the two map styles are also difficult to discern.

Council’s exclusion of multiple bushland sites from ‘Community Land’ status (protection)

Based upon a quick comparison of the two maps, we have concern for the following identified land parcel proposed for removal from current Council –owned Community Land included within The Gully Aboriginal Place, and we ask Council what it the justification and have explanation before this 2021 Draft Plan of Management goes before Council to be approved.

This site is the bushland block across the road from the Katoomba Sports and Aquatic Centre which covers about a hectare at address 34-46 Gates Avenue.

This natural bushland block significantly represents one of the last natural landscapes interconnecting The Gully between the northern section and the central section. It must be naturally preserved intact as part of The Gully’s Community Land zoning (land categorisation).

Close inspection of Council’s proposed re-categorisation of Community Land map, shows that this site has been excluded from Council’s Community Land in The Gully Aboriginal Place. The logical presumption is that Council intend to rezone it ‘Operation Land’ so Council can then legally sell the hectare off to private land use developers into for or five housing lots. So the bushland gets bulldozed and Council management profiteer with a million dollar bounty.

On the above bases, we reject Council’s current (2021) proposed re-categorisation of Council-owned community land in the Gully.

Our concerns above were contributed by The Habitat Advocate to Council in its dedicated Public Hearing held via Zoom online software on Saturday 7th August 2021 as well as with a follow up email dated 12th August 2021 to Council’s delegated Environmental Planning Officer Soren Mortensen. However, no acknowledgement of that email has been received from Council.

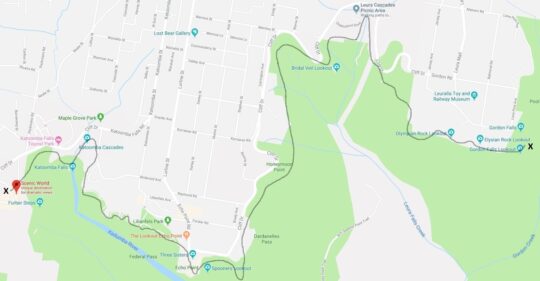

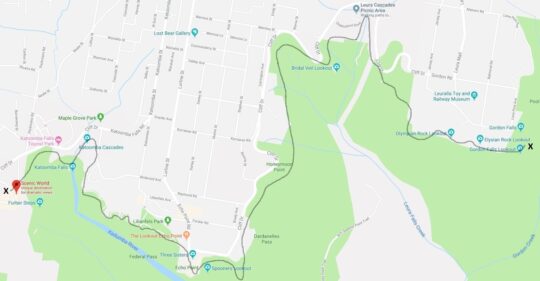

We have sourced land title mapping of The Gully Water Catchment from Google Maps dated 2021. There are six maps that cover the water catchment extent of The Gully extending from the Cox’s watershed (Great Western Highway) in the north, down through what was Frank Walford Park and Catalina Raceway, as well as the side watercourse through Selby Reserve (from Hinker Park), and the two watercourses that flow from the west and then to Katoomba Falls Reserve and to Katoomba Falls itself.

We have compared Council’s proposed land re-categorisation map (Figure 4 above) with the land titles on these six mapped sections from Google Maps, and placed an ‘X’ on each identified the land parcel that are bushland within The Gully but which have been excluded in Council proposed recategorisation.

Not all these bushland lots are Community Land, but many are. Bushland and swampland land parcels that are categorised by Council as ‘Community Land’ are generally protected from land use development. However those bushland and swampland land parcels that are excluded from Council’s colouring in Figure 3 above, are NOT protected. Council could then easily rezone them as ‘Operation Land’ which is the next stage before selling them off for housing development. Council has a record or doing this throughout the Blue Mountains local government area over decades, including on the periphery of the Gully.

What we wish to illustrate here in these six maps is the scale to which the bushland amenity risks being destroyed for likely housing development and so alter the natural amenity of The Gully forever.

Each map below is in Adobe Acrobat (PDF). We allow for each map to be zoomed into so as to enable enlarging the map on the screen via Google Docs (free software), as well to be downloaded and printed.

Further Reading:

[1] The Gully Report No. 8, ‘Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study‘, published in 1993, by F.J. Bell and Associates Pty Ltd, (Fred Bell), Sutherland NSW, contains 87 pages in A4 spiral softcover binding, (available internally on this website) >https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/gully-report-no-8-the-bell-report-of-1993/

[2] The Gully Collection, by The Habitat Advocate (available internally on this website), > https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/consultancy/the-gully-in-katoomba/the-gully-collection/

Excavator in The Gully getting stuck in with Council approval. We don’t forget. This is comparable of how Council forcibly evicted the original residents back in 1957. (Photo by Editor Sunday 17th February 2008).

Sunday, August 8th, 2021

The Gully: Blue Mountains {city} Council’s notice of an updated Plan of Management for its 2004 plan, being on public exhibition in 2021. It was only 7 years overdue.

Council’s current review of The Gully Plan of Management (2004) has been undertaken over the past five years between 2017 and 2021. Council has published four key reports in this review process currently published on Council’s webpage: https://yoursay.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/gully-plan

These four key reports are as follows:

Report A: Upper Kedumba River Valley – Plans of Management (revised edition 2004)

Report B: The Gully – Stakeholder Engagement Report [2018-2019] (June 2019)

Report C: Public Hearing for Proposed Recategorisation of Community Land in The Gully Aboriginal Place (July 2021)

Report D: The Gully Aboriginal Place Draft Plan of Management (7th May 2021)

We anticipate that Council’s above outsourced ‘yoursay…’ webpage will likely be publicly available only for the duration of Council’s current review process, then it will be deleted by Council soon after Council’s review process has concluded. So in the local community interest, since these reports and their research have been both publicly funded and concern a public place ‘The Gully’ in Katoomba, we herein provide an enduring online record for the interested public.

Each of these reports are provided below as links to the same reports stored internally on our website in Adobe Acrobat format and available to the public to download and to print…

A: Upper Kedumba River Valley – Plans of Management (revised edition 2004)

>Upper Kedumba River Plans of Management – revised edition in 2004

B: The Gully – Stakeholder Engagement Report ‘Talking with the Community’ (2018-2019) (Report dated June 2019)

>The Gully – Stakeholder Engagement Report (June 2019)

C: Public Hearing for Proposed Recategorisation of (Council-owned) Community Land in The Gully Aboriginal Place (Report dated July 2021)

>Public Hearing for Proposed Recategorisation of Community Land in The Gully Aboriginal Place (July 2021)

D: The Gully Aboriginal Place Draft Plan of Management (Report dated 7th May 2021)

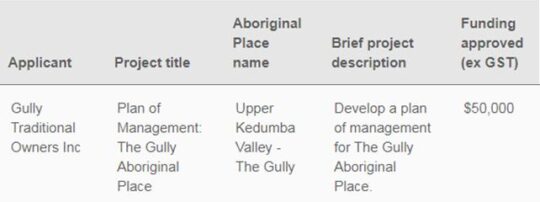

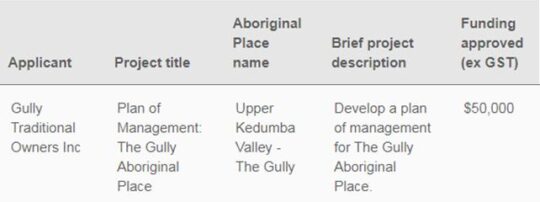

Preparation of this draft document was partly funded by Blue Mountains Council and supplemented by the NSW Government out of its ‘NSW Heritage Grants – Aboriginal Heritage Projects’ in 2017-2018 from NSW taxpayer funding, that is, by the wider general community.

SOURCE: ^https://www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/grants/grants-recipients/2017-18-heritage-grants/ SOURCE: ^https://www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/grants/grants-recipients/2017-18-heritage-grants/

This draft document comprises some 140 pages with an Adobe Acrobat file size of 22 MB. So for community access and download convenience, we have divided the original document into smaller sections in order via hyperlinks internally within our website to sections in Adobe Acrobat format, each of which is downloadable to the general public in perpetuity. We consider this is in the public interest since the community lands concerned within The Gully are publicly owned through Council and the draft plan has also been public funded.

- >Contents and Foreword

- >Executive Summary

- >Introduction

- >The Gully is Country

- >A Declared Aboriginal Place

- >Working with Legislation

- >Speaking with the Community

- >Caring for Country

- >Implementation

- >Monitoring and Review

- >References

Background

‘Blue Mountains Council* ‘has prepared a Draft Plan of Management (PoM) for The Gully Aboriginal Place in accordance with the requirements of the Local Government Act 1993 and the Crown Land Management Act 2016, and Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) Declared Aboriginal Places Guidelines for Developing Management Plans.

The Draft Plan of Management updates the 2004 Plans of Management for Upper Kedumba River Valley, covering the Blue Mountains City Council managed community lands within The Gully including Frank Walford Park 2003, Katoomba Falls Reserve McRae¡¦s Paddock Section and Katoomba Falls Reserve Cascades Section 2003. The draft 2021 Plan of Management for The Gully includes the addition of three parcels of Crown land, covering all public land within The Gully Aboriginal Place.

Council has placed The Gully Aboriginal Place Draft Plan of Management on public exhibition for comment until Monday 26 July 2021. The Draft Plan of Management is available to view online at the Blue Mountains City Council website https://yoursay.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/gully-plan

The existing community land categories (as defined under Section 36 of the Local Government Act 1993) over Council managed land are being amended to:

-

- Remove the Sportsground category over the race track in Frank Walford Park to be replaced by the Natural Area category;

- Reflect changes in boundaries between the Park and General Community Use categories in Frank Walford Park;

- Reflect an update to vegetation mapping within the Natural Area category in Frank Walford Park, McRae’s Paddock and Katoomba Falls Reserve.

The proposed recategorisation of these parts of The Gully Aboriginal Place is set out in the Draft Plan of Management and in Section 3 of this document.’

NOTE 2: We do not expect that Council’s above hyperlink will last for very long, hence why we have downloaded Council’s’ publicly funded documents to our website in the public interest.

* NOTE 2: The Habitat Advocate disagrees with Council’s propaganda to incorporate the word ‘City’ into its organisational title.

Katoomba Falls Creek (in 2002 Council unilaterally renamed the creek ‘Upper Kedumba River’)

Community Consultation Restricted (yet again)

Council’s chosen community consultation process continues to be restricted on a one-way basis. Members of the community only have the choice of the following one-way communication means:

A. Internet by mandatory registration and completing an online submission form at https://yoursay.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/gully-plan

B. In writing by: email: council@bmcc.nsw.gov.au Attention: Andrew Johnson/Soren Mortensen; and to Environmental Planning Officer smortensen@bmcc.nsw.gov.au

C. In writing by post to Blue Mountains City Council, Locked Bag 1005, KATOOMBA NSW 2780 Attention: Andrew Johnson/Soren Mortensen

No public forum either face-to face or online was offered by Council to the general community. The only public forum offered by Council to the general community was a Public Hearing held on Saturday 8th August 2021 (1pm-3pm). This hearing took place via Zoom meeting software in compliance with the NSW Government’s public health order social lockdown in response to the Coronavirus pandemic.

However, this ‘public hearing’ did not address this Draft Plan of Management, but was instead strictly limited to Council’s proposed re-categorisation of various land parcels throughout The Gully gazetted as ‘Council-owned Community Land‘.

The only material provided by Council on this specific sub-topic was a table and two tiny maps. This was not made clear in advance to the community participants (which numbered just 32).

The material relevant to the public hearing was actually not part of the Draft Plan of Management, but in a quite separate document entitled ‘Public Hearing For Proposed Recategorisation of Community Land in The Gully Aborigional Pace – Background Information‘, dated July 2021. This hearing was only offered by Council only because legally Council had to comply with Section 40A of the Local Government Act 1993, which as at 10th June 2021 reads as follows:

‘LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1993 – SECT 40A: Public hearing in relation to proposed plans of management

(1) The council must hold a public hearing in respect of a proposed plan of management (including a plan of management that amends another plan of management) if the proposed plan would have the effect of categorising, or altering the categorisation of, community land under section 36(4).

(2) However, a public hearing is not required if the proposed plan would merely have the effect of altering the categorisation of the land under section 36(5).

(3) A council must hold a further public hearing in respect of the proposed plan of management if–

(a) the council decides to amend the proposed plan after a public hearing has been held in accordance with this section, and

(b) the amendment of the plan would have the effect of altering the categorisation of community land under section 36(4) from the categorisation of that land in the proposed plan that was considered at the previous public hearing.’

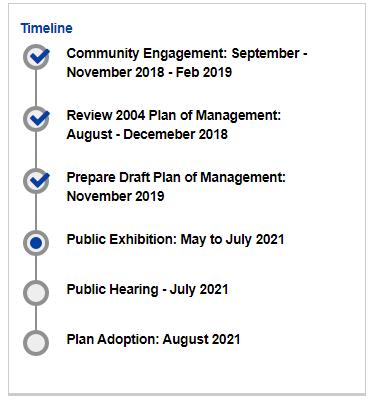

Planning Review Timeline:

Monday, December 21st, 2020

We herein enclose a complete copy of Blue Mountains {city} Council’s 2004 Plan of Management for Upper Kedumba River Valley, which we term The Gully Water Catchment. It was formerly gazetted by Council as Katoomba Falls Creek Valley for decades prior to its unilateral renaming by Council in 1995.

[Editor’s note: We reject the urban assertion by Blue Mountains City Council (BMCC) councillors that the Blue Mountains could or should be in any way labelled as a “city” as if comparable with Sydney. So we choose to place the word {city} in BMCC’s title in brackets.]

The Gully Water Catchment lies on the western edge of the regional township of Katoomba in the Blue Mountains region, located 100km due west of Sydney’s CBD.

The Valley takes that shape of an elongated valley from a natural amphitheatre in the north southward and features various natural riparian zones around watercourses that confluence into a central creek across this section of the Blue Mountains plateau to Katoomba Falls.

Katoomba Falls tumbling down into the Jamison Valley

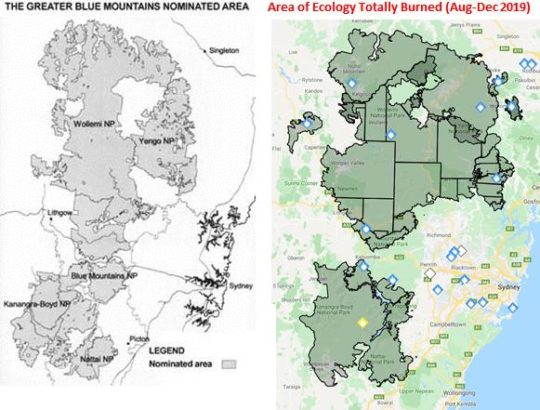

The Gully Water Catchment is situated on the Blue Mountains central plateau and covers (290 hectares/2.9 km2) and lies wholly within the watershed ridgeline of Bathurst Road to the north, meandering along the watershed through central Katoomba to the east, the ridgeline along Valley Road to the Jamison clifftop escarpment to the west, and to Katoomba Falls to the south.

The water plunges into the Kedumba River into the Jamison Valley 300m below the Blue Mountains plateau which then flows downstream for about 50km to the artificial Lake Burragorang above Warragamba Dam.

This dam was built in post-WWII from 1948-1960 to provided a fresh water reservoir for an ever-growing Greater Sydney for it’s primary drinking water. Before the construction of the dam, Burragorang Valley had been inhabited by white settlers since the 19th century, and for thousands of years before, the Burragorang valley was part of the tribal lands of the Gundungurra Aboriginal people, who became displaced local Aboriginal refugees in their own country.

In 1948 some fled to squat in the small valley they were familiar and had family connections with, situated about 40 km to the north they nicknamed The Gully on the edge of Katoomba.

The natural sedge swamp within the northern part of The Valley (The Gully), previously referred to as ‘Frank Walford Park’. The sky blue sign with white lettering by the lake across from the derelect Madge Walford Fountain was secretly removed a few years ago (2019?) presumably by Blue Mountains {city} Council.

Katoomba Falls Creek Valley was unilaterally renamed by Blue Mountains {city} Council in its wisdom around 1995 to being renamed ‘Upper Kedumba River Valley‘.

Why the name change? Well, from experience in dealing with Blue Mountains {city} Council in relation to this valley (2002-2007) one suspects that it was part of Council’s relentless ‘divide and conquer strategy’ to undermine then in 1996, what had been a decade long struggle by local resident group Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Inc. (The Friends) to save and protect The Valley from ongoing threats of destructive harm and neglect and to seek a joint co-operative land management between the interested local community and Blue Mountains {city} Council.

The Valley includes the Aboriginal Place (AP) affectionately known by former residents as ‘The Gully’. They were a mix of poor folk, a few dozen or so, who subsisted on the edge of town either renting or squatting in very basic shack-style homes. That is until Blue Mountains {city} Council back in 1957 decided to forcibly evict them all and bulldoze their dwellings to build a motor racing track for an elitist wealthy motor racing fraternity. For many years this northern part of The Valley used to be called Frank Walford Park, after a previous Council mayor.

Subsequently over the years since, Blue Mountains {city} Council has incrementally sold off numerous land parcels to private housing development so as to boost its revenue base. The remnant bushland sections are gazetted as ‘Community Land’ under the New South Wales Local Government Act 1993.

Despite The Valley naturally being a riparian zone (mostly wetland) of the creek and its various headwater streams, the community land have become quite separated as Council has unilaterally re-zoned various land parcels on paper from being ‘Community Land‘ to ‘Operational Land‘, invariably in preparation to be flogged off for housing. History records many land sales by Blue Mountains {city} Council throughout The Valley sold by either for private housing, Katoomba Sports and Aquatic Centre and for what is called South Katoomba Rural Fire Service Station.

Beneath the surface, Council dug up the wetland and installed a massive sewer network.

Council’s 2004 Plan of Management (POM) for The Gully

Council had this 2004 POM document initially compiled in draft form in October 2002 by external consultancy, Environmental Partnership, which is off-Mountains based in distant Ultimo in central Sydney. These dudes do urban landscapes, not natural landscapes – so were they an appropriate choice by council? Well, it depends upon the outcomes council wanted to The Gully plan of management back then. Council filed it anyway.

The POM draft was subsequently revised over a two year period and the final document has the rather lengthy bureaucratic title thus: ‘Upper Kedumba River Valley Plans of Management Covering the Community Lands within “The Gully” Aboriginal Place’ (Revised Edition 2004).

Ok, so the names were evolving and former council mayor Frank Walford, who supported the racetrack usurpation of 1957, and by 2004 was getting out of favour with council due to expressed criticism of his namesake in The Gully by the former residents of The Gully. We note that council’s sky blue coloured ‘The Frank Walford Park’ sign also suddenly disappeared in recent years.

So the ‘subject lands’ exclusively described as ‘“The Gully” Aboriginal Place’ are shown in this map on page 6.

The total area of The Gully Aboriginal Place (defined as being of “cultural significance”) are 44 hectares (43.92ha on page 44 to be precise) for Frank Walford Park, plus 14 hectares (13.74 ha on page 58 to be precise) for McRaes Paddock, plus 8 hectares (7.86 ha on page 63 to be precise) for Katoomba Falls Reserve Cascades Section (Selby Street Reserve). So Council’s 2004 definition for the entire area of The Gully Aboriginal Place was 65.52 hectares, to be precise.

This 2004 iteration stipulates three separate plans of management, one for each of the geographic public land sections of The Valley. It excludes the sizeable western side of The Valley referred to as Katoomba Golf Course – which was and still is public land owned by Blue Mountains {city} Council. It also excludes the watercourse and riparian zone to the west between Wellington Street and Stuarts Road in Katoomba, which is at the time was private pastoral land addressed as 21 Stuarts Road.

The public (Community Land) sections of The Valley included in the document, form a natural riparian corridor along Katoomba Falls Creek, they being:

- Frank Walford Park (comprising the northern headwaters of Katoomba Falls Creek)

- McRae’s Paddock (comprising the main centre section of Katoomba Falls Creek)

- Selby Street Reserve (comprising a eastern side tributary to Katoomba Falls Creek which confluences with Katoomba Falls Creek at Maple Grove Park, as well as the sports ovals and the escarpment top riparian zone to the top of Katoomba Falls)

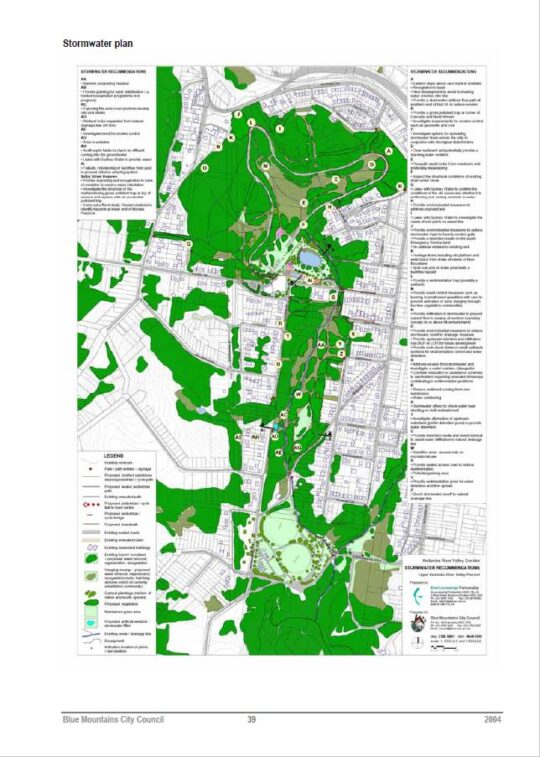

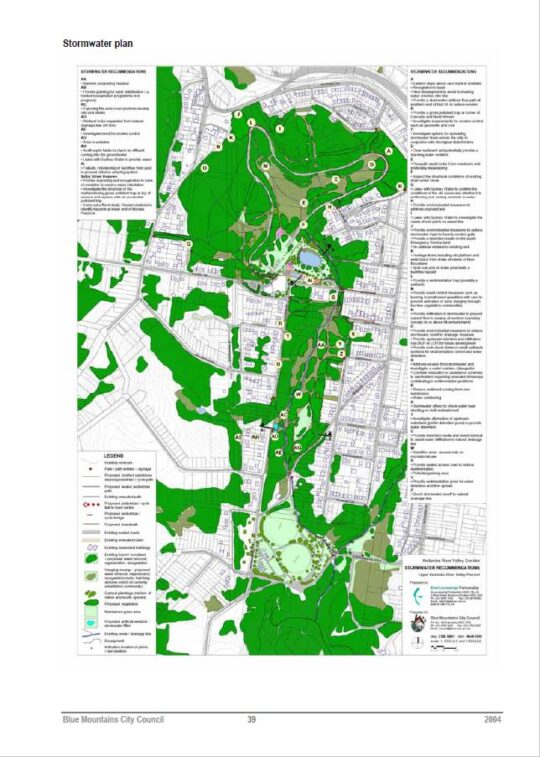

In addition on page 39 of the 2004 Plan of Management there is a 35-point Stormwater Plan for The (entire) Valley.

Council’s Legacy of Planned Inaction for The Valley

These 2004 plans of management (x3) along with the Stormwater Plan were never acted upon by Blue Mountains {city} Council. This is despite the considerable cost of all the research and compilation of preparing the 2004 plans over more than two years, which likely exceeding $100,000.

These plans follow a series of similar plans compiled for this creek valley, which we have on file are:

- (no date) Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study A & B

- (no date) Frank Walford Park – Bushland Management and Report

- 1955: Frank Walford Park Master Plan for Development, 1955 (car racetrack), by Katoomba Municipal Council (Ed: better name)

- c.1980: Draft Assessment of Frank Walford Park, Katoomba – Land Suitability, Environmental Constraints

- 1981: Frank Walford Park Management Plan, by BMCC, 54 pages

- June 1993: Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study – Part 1 Draft Report and Management Plan by F.& J. Bell & Associates, for BMCC, 85 pages

- June 1993: Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Environmental Study – Part 2 Technical Reporrts, Data and Analysis by F.& J. Bell & Associates, for BMCC, 55 pages

- April 1996: Katoomba Falls Creek Valley – Draft Pan of Management and Report, by Connell Wagner Pty Ltd (consultancy), (for BMCC) approx. 200 pages (inconsistently numbered)

- 3rd July 2000: Upper Kedumba Valley, Katoomba – Report on Cultural Significance…, (for NPWS) by Dianne Johnson with Dawn Colless, 162 pages

- 2001: Area 2 Community Plan (including Katoomba) by Area Community Planning, BMCC, 102 pages

- 2001: Area 2 Sport and Recreation Plan (including Katoomba) by Area Community Planning, BMCC, 107 pages

- 2004: Upper Kedumba River Valley Plans of Management Covering the Community Lands within “The Gully” Aboriginal Place (Revised Edition 2004), by Environment Partnership (consultancy) for BMCC, 105 pages

- August 2005: A Heritage Study of the Gully Aboriginal Place, Katoomba, New South Wales by Allan Lance of heritage Consulting Australia Pty Ltd & NSW Dept Environment and Heritage (for BMCC), 113 pages

- March 2005: Catchment 7 Improvement Grant No.44 Upper Kedumba River Valley, by members of Kedumba Creek Bushcare & BMCC – Final Report for Sydney Catchment Authority, 27 pages

- June 2006: Hawkesbury Nepean River Health Strategy Volume 1, by Hawkesbury Nepean Catchment Management Authority, 78 pages

- June 2006: Hawkesbury Nepean River Health Strategy Volume 2, by Hawkesbury Nepean Catchment Management Authority, 144 pages

- June 2019: The Gully – Stakeholder Engagement Report (June 2019), 44 pages

- 29th September 2021: Proposed Recategorisation of Parts of the Gully Aboriginal Place, Katoomba – Public Hearing and Submissions Final Report, by Parkland Planners for BMCC, 56 pages

- 4th October 2021: The Gully Aboriginal Place Plan of Management, by BMCC, 145 pages.

Not one of the plans above for The Valley has been acted upon by Blue Mountains {city} Council to date since that of 1981. This is disingenous and shameful. It is no wonder that The Friends [1989-2016] became exasperated with Blue Mountains {city} Council and it’s ‘all-talk-no-action‘ recalcitrance on The Valley over the years.

It noteworthy that the chambers of Blue Mountains {city} Council is situated just 200 metres from the eastern ridge top of The Valley’s northern amphitheatre as the crow flies – so close geographically, yet shunned. It seems that since time immemorial nothing’s changed from the time The Valley (Gully) community of struggling ‘have nots’ (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal alike) on this edge of town were shunned by the ‘haves’ uphill of Katoomba and nearby villages.

One would not be surprised if the combined cost of Blue Mountains {city} Council’s compiling of all these plans and reports on The Valley exceeds a million dollars. The funding came from local ratepayers else from grant moneys received from the New South Wales Government. Indeed, one would not be surprised if once each plan was finalised, that Council instantly filed it to gather dust on an archival shelf, such is one’s experience as a former member of the Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley Inc.

Copies of the above plans and reports over time we shall publish in The Gully Collection on this website, available for free download and printing to the general public. Access to the ‘The Gully Collection’ is by clicking on The Gully Collection’ photo image on the front page of this website.

Stipulated Plans of Management for Council Community Lands

Under Section 36, of the New South Wales Local Government Act 1993, each local government (local council) throughout New South Wales is legally required to prepare a plan of management for a Community Land area under Council ownership. This means that in the case of the Blue Mountains {city} Council, it is compelled to draft plans of management for each community land area and update these plans from time to time, including the community land within Upper Kedumba River Valley.

Under Section 36 of the Act:

- “A council must prepare a draft plan of management for community land.

- A draft plan of management may apply to one or more areas of community land, except as provided by this Division.

- A plan of management for community land must identify the following:

(a) the category of the land,

(b) the objectives and performance targets of the plan with respect to the land,

(c) the means by which the council proposes to achieve the plan’s objectives and performance targets,

(d) the manner in which the council proposes to assess its performance with respect to the plan’s objectives and performance targets, and may require the prior approval of the council to the carrying out of any specified activity on the land.”

The New South Wales Local Government Act 1993 in fact superseded previous local government Acts that date back to 1919. So the above list where it refers to a plan of management, likely similarly was a required document under the NSW legislation. So the plans of management prepared for Blue Mountains {city} Council have always been mandatory, rather than being some noble gesture by Blue Mountains {city} Council seen to be doing the right civil thing for the local community.

In addition, in the case of selected surviving remnant bushland sections of community land connected with local Aboriginal cultural heritage within the Upper Kedumba River Valley, since 18th May 2002, ‘The Gully’ was declared an Aboriginal Place (AP) by Blue Mountains {city} Council and the NSW Parks Service under Section 84 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW) No 80.

Under Section 72 of National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 No 80 ’72 Preparation of plans of management’ “The Secretary.. (d) may from time to time cause a plan of management to be prepared for any Aboriginal area or wildlife refuge.”

2004 Action Plans not acted upon by Blue Mountains {city} Council

The stipulated Action Plans of the Upper Kedumba River Valley Plans of Management of 2004 were not acted upon by Blue Mountains {city} Council in the intervening seventeen years between 2004 and the current 2021 Plan.

Refer to the supplied copy of the document below – both the Action Table (pages 69-74) and Appendix B (pages 83-94). Council senior management will respond excusing lack of external grant funding (usually from the New South Wales Government), but then they won’t be able to provide any evidence of applying for such funding.

Council simply doesn’t care. It only prepares plans of management because it is legally required to do so under Section 36, of the New South Wales Local Government Act 1993 and also under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 No 80.

Under the latter, Section 79A ‘Lapsing of plans of management‘ stipulates:

“(1) A plan of management for lands reserved under Part 4A expires on the tenth anniversary of the date on which it was adopted unless it is sooner cancelled under this Part.

(2) Not less than 6 months before a plan of management expires, the board of management for the lands concerned must prepare a new plan of management to replace it.

(3) The board of management is to have regard to a plan of management that has expired until the new plan of management comes into effect.”

Blue Mountains {city} Council delayed its review of its 2004 Plan some seventeen years. Not including the NSW bushfire emergency declarations of 2019 and the Coronavirus Pandemic 2020-2021, council’s review process was still an inexcusable five-year delay between the due scheduled review in 2014 and when council initiated community engagement from 4th September 2018.

This is evidencial from Blue Mountains {city} Council’s Stakeholder Engagement Report concerning The Gully dated June 2019, page 7 extract as follows:

Extract of Page 7 ‘Methodology’ of Blue Mountains Council’s Stakeholder Engagement Report, June 2019, pre-empting its POM for The Gully 4th October 2021

The image below is the Stormwater Plan for The Valley as part of the 2004 Plan of Management for The Valley on page 39. There are some 35 specific actions identified, explained and specifically geo-located on the map. The clarity of the image is regrettably poor and almost impossible to read. It has been sourced from the 2004 Plan of Management on Blue Mountains {city} Council’s website concerning the 2021 POM; perhaps the poor clarify of the image was intentional?

Council failed to act on any of the 35 recommended actions of the Stormwater Plan.

Council failed to act on any of the recommended actions of the Bush Regeneration Plan. The only work carried out in The Valley was the ongoing weeding by local residents associated with the Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley bushcare groups. One group focused on the Frank Walford Park area, another along Selby Street Reserve and a third in MacRae’s Paddock.

There was supposed to be stream restoration works, a Heritage Management Plan, native re-vegetation, macrophytle planting around Horace Gates’ artificial lake, removal of the derelict toilet blocks, contruction of a heritage centre and installation of picnic shelters. There was to be a paid re-vegetation coordinator supported by some 20 trainee staff. None of that happened. These are all listed in a Action Plan Table in Section 8.2 of the 2004 Plan of Management from page 71 to 74.

Unbelievably, the total budgeted cost of Blue Mountains {city} Council’s wish list for the entire ‘Masterplan‘ for The Valley came in at a staggering pie-in- the-sky $4,682,000!

The funding for all this was supposed to be gleamed from grants from various departments of the New South Wales Government such as the NSW Department of Conservations and Land Management, the NSW Heritage Office and somehow from from State Treasury, in theory.

That didn’t happen because Council didn’t actually apply for any grant funding for these listed projects.

So what did Council actually manage to do for The Valley over these 17 years (2004-2021) ?

Funding that was secured between the 2004 Plan and the 2021 Plan was from a joint Aboriginal grant between The Gully Traditional Owners (Gundungurra) and the Widjabul traditional custodians the Wilson River region near Lismore in the northern rivers region of New South Wales. A grant of $600,000 was obtained through partnership with Rous Water and Sustainable Futures Australia as part of the Aboriginal ‘Reconnecting to Country‘ project. The funding was used to construct a boardwalk and interpretative Aboriginal signage in the northern (formerly Frank Walford Park) section of The Gully.

A local Aboriginal interpretative pathway design was initiated by the local Aboriginal people in The Gully, not by Council. The entire $600,000 went into funding a cultural focus about the stories of previous residents forciblly evicted for Council’s motor tracing circuit. The funding was not about environmental rehabilitation of The Valley. Also, a small section of the Catalina Racetrack sleeper fencing was removed near Catalina Lake as a symbolic gesture of finally ending the motor racing usurpation of The Valley since 1957.

Since The Gully was declared an Aboriginal Place on 18th May 2002, motorised use of the track was prohibited by Blue Mountains Council. This ending of the racing era in The Valley came about mainly through the conserted campaigning by local resident activist group the Friends of Katoomba Falls Creek Valley from 1989 to end the racing and the noise. Others wish to claim the credit.

However, occasional mischievous motorised access persisted from time to time for a few years. The steel gate was illegally towed out of its concrete base near the South Katoomba Rural Fire Station in order for someone to gain vehicle access to the old race track. A second steel gate was also illegally removed nearby the Aquatic Centre to gain vehicular access to the track. The odd trail bike and mini bikes were observed by this author illegally racing as recently as December 2005.

During this period , a coppice of willow trees were professionally removed from inside the racetrack, near the disused toilet block. An Aboriginal Liaison Officer, Reg Yates, was employed by Blue Mountains {city} Council for a short time in around 2006. The Council-owned cottage at 23 Gates Avenue was donated to newly formed Gully Traditional Owners, after the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institiute (BMWHI) relocated. The building is occasionally used currently as an office, and meeting place for Gundungurra use. A small art gallery was constructed adjacent. As a local resident, this author usually observes that most of the time the premises are closed and all the window blinds are pulled down.

The Gully Cottage at 23 Gates Avenue in Katoomba. For decades through the 1980s up until 2004 the cottage lay empty after the prevous caretaker had relocated. Council leased the cottage in 2004 to the BMWHI for a penny rent of $1 per year. Then Council gifted it to the Gully Traditional owners and spend tens of thousands renovating it.

At the end of 2011, Blue Mountains {city} Council in partnership with NSW Landcare established a volunteer-based Garguree Swampcare group tasked to rehabilitate the riparian swamp/wetland areas from weed infestations inside The Gully, as well as re-landscaping and planting out locally native vegetation. The name ‘Garguree’ means ‘gully’ in Gundungurra language, apparently according to local historian Jim Smith Ph.D.

We enclose below a complete copy of the final revised Plan of Management of 2004 in Adobe Acrobat .PDF format below. Being a publicly funded community document wholly concerning community land, this document below is freely available to the public for download and printing.

Saturday, May 16th, 2020

The Blue Mountains conservation grapevine has alerted Leura locals to a new development threat atop the Jamison Escarpment. It’s seems to be all about facilitating mass tourism and its coming from the custodial land holder itself, the so-called National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

Trust NPWS?

Apparently, local residents were letterbox dropped on 22nd April 2020 by NPWS. Its Community Information Letter on official NPWS letterhead outlined a project proposal described as the “Gordon Falls Lookout accessibility upgrade“. Accessibility upgrade for whom? Busloads overflowing from nearby congested Echo Point?

It is flagged to be part of some grander “Grand Cliff Top Walk“, and it seems NPWS has already selected a construction contractor, NewScape Designs from inner Sydney.

The colourful ‘artist’s impression’ of this proposal: it’s not what you know, but who you know in the NSW Government. The colourful ‘artist’s impression’ of this proposal: it’s not what you know, but who you know in the NSW Government.

So why is Gordon Falls Lookout targeted for tourism development?

Well, NPWS’s distributed Community Information Letter to nearby Leura residents reads as follows:

Loading...

Loading...

So NPWS is calling this tourism development its ‘Gordon Falls Lookout Accessibility Upgrade‘. So it is all about providing disabled access is it?

According to the 2020 sales pitch of NPWS for this tourism infrastructure proposal, it’s apparently just an “upgrade” for Gordon Falls Lookout, not a new development, but this smells of legislative avoidance speak. The entire project is wholly within the Greater Blue Mountains Area, and Sydney Water Catchment, so with such a proposal clearly NPWS are keen to not trigger any sense of ‘development’ (which it obviously is).

The authority behind this Community Information Letter is…

These public servants are invariable in ‘Acting’ responsibilities akin to casuals. Should they stuff up, then their acting days are immediately over. These public servants are invariable in ‘Acting’ responsibilities akin to casuals. Should they stuff up, then their acting days are immediately over.

The overarching policy and funding is coming out of NSW Premier Gladys Berijiklian‘s tourism infrastructure programme dubbed ‘The Improving Access to National Parks Programme‘. Publicly announced on 9th February 2019, the programme funding is almost $150 million in capital expenditure budgeted to span four years (2019-2023).

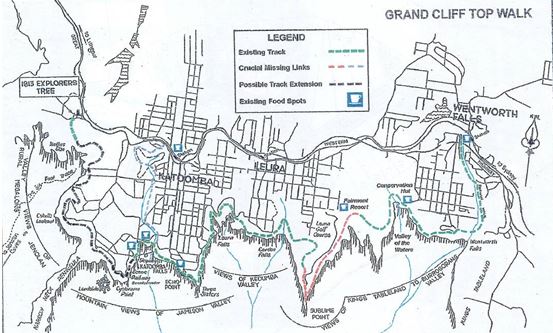

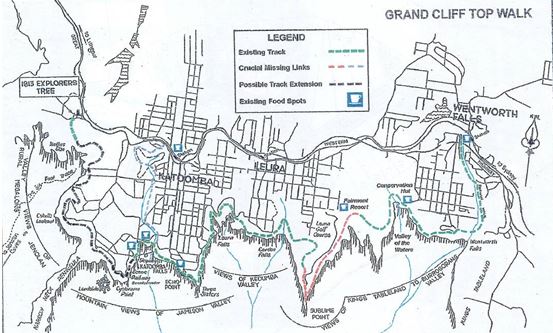

“This includes major upgrade works in places like Sydney’s Royal National Park and in the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, making it easier for people to enjoy our wonderful natural beauty,” Ms Berejiklian said. The funding is to “upgrade” walking tracks, better visitor infrastructure and facilities, etc. Specifically the Gordon Falls Lookout Accessibility Upgrade is part of a masterplan to “upgrade” a 13.6 kilometre Grand Cliff Top Walk from Wentworth Falls to Katoomba in the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area costing $10 million, and “upgrading” access to iconic lookout points to a mobility impaired access standard (another $10 million).

The problem is that the 13.6 kilometre Grand Cliff Top Walk from Wentworth Falls to Katoomba does not exist. Prince Henry Cliff Walk extends from Scenic World to Gordon Falls. But there is no track east of Gordon Falls, not yet anyway, just untouched bushland to Sublime Point to the back of the Fairmont Resort in Leura. So this masterplan is not an upgrade but a new tourism infrastructure development.