August 17th, 2011

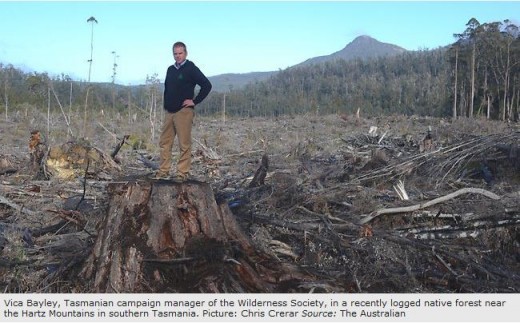

The following article was initially published by The Wilderness Society (NSW) on its website 20110809. Reproduced with permission from The Wilderness Society (NSW):

.

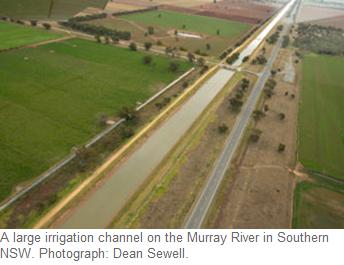

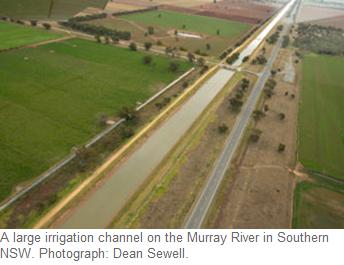

Economists say water buybacks can save the Murray-Darling River

A senior economist at The Australian National University (ANU) says that subsidising water infrastructure will not deliver the volumes of water needed to return the Murray-Darling River system to health.

Professor Quentin Grafton from the Crawford School of Economics and Government at the ANU says that despite the Australian Government making commitments to spending $5.8 billion on infrastructure designed to increase water efficiency, this will have little impact on increasing flows through the ailing system.

“That’s probably going to get the government about 500 gigalitres. So to put that in perspective, that’s a fraction of the sorts of numbers we need in terms of volumes for the rivers“, said Prof. Grafton.

“By contrast, if we were to purchase water entitlements from willing sellers, we can get the volumes that we need”.

.

Water Buyback a Sound Approach

.

The Productivity Commission has supported this view, calling for some of the money allocated to infrastructure to be redirected to other initiatives, including water buybacks from willing sellers and support for affected communities.

“A general conclusion is that purchasing water from willing sellers is a sound approach to meeting the Australian Government’s commitment to obtain additional water for the environment. Indeed, it should be the preferred method for recovering water, taking precedence over subsidising investment in water saving infrastructure“, concluded the Commission.

While big irrigation companies continue their scare campaign saying that water buybacks will have a negative economic impact on the agricultural industry, a model proposed by Prof. Grafton concluded that irrigators would be adequately compensated.

“If the $8.9 billion currently budgeted for water reform were spent in a cost effective manner on the purchase of water entitlements rights from willing sellers, and with no arbitrary restrictions on water trade, the Australian government would be able to increase environmental flows by at least 4,000 gigalitres per year, fully compensate irrigators for reduced extractions, and have funds left over.”

This is a much better alternative than committing massive financial resources to infrastructure that will not save the Murray-Darling River.

^http://annamariacom.blogspot.com/2010/10/murray-darling-basin.html ^http://annamariacom.blogspot.com/2010/10/murray-darling-basin.html

.

More Willing Sellers than Tenders

.

Far from being unpopular with many farmers, recent tenders for water buybacks have been oversubscribed, with the majority of sellers only parting with a portion of their entitlements and using the capital raised to improve efficiency or diversify their businesses.

The Australian Government needs to spend the $10 billion of taxpayers’ money allocated to save the river system wisely and ensure the rivers flow, or give the Australian people their money back.

With the health of the rivers and the communities that rely on them at stake, we need economically responsible action that ensures that the rivers keep flowing whilst building stronger, more economically diverse and sustainable rural communities.

Prof. Grafton concluded that, “Unless we spend most of the money on the buying of the water entitlements, we won’t have sufficient flows for the rivers, and that’s a critical point. Because otherwise, we’ll end up spending billions and billions of dollars, we won’t get sufficient volumes for the rivers so we’ll have the problem we’ve gone through in the last few years come back again.”

“The communities will continue to be in a trouble because they won’t get the support that they need, and we’ll end up in a few years time with lots of concrete channels but no water”.

[Source: ^ http://www.wilderness.org.au/regions/new-south-wales/water-buybacks-can-save-the-river]

Andrew Tatnell, dying River red gums at Chowilla, South Australia in 2004

Photo by Andrew Tatnell

[Source: ^http://www.sauer-thompson.com/archives/opinion/2004/04/ironbar-cracks-again.php] Andrew Tatnell, dying River red gums at Chowilla, South Australia in 2004

Photo by Andrew Tatnell

[Source: ^http://www.sauer-thompson.com/archives/opinion/2004/04/ironbar-cracks-again.php]

.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘Modelling Water Trade in the Southern Murray-Darling Basin‘, 2004, by The Productivity Commission, ^http://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/60474/watertrade.pdf

[2] Murray Darling Basin Authority, ^http://www.mdba.gov.au/basin_plan

[3] ABC Four Corners, background reading on the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, 2011, ^http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/content/2011/s3157128.htm

[4] Hawke Institute, University of South Australia, ^http://www.unisa.edu.au/hawkeinstitute/research/ecosocial/eco-case-study.asp

[5] Murray Darling Association, ^http://www.mda.asn.au/index.cfm?objectid=531DFD7D-D372-0C96-D485B3EAC56F6BF9

[6] Act Now, ^http://www.actnow.com.au/Issues/MurrayDarling_Basin.aspx

[7] Save the Murray, ^http://www.savethemurray.com/

[8] Murray Futures, ^http://www.murrayfutures.sa.gov.au/lower.php

[9] Hurry Save the Murray, ^http://hurrysavethemurray.com/

[10] Murray Darling & the Coorong, ^http://rachel-siewert.greensmps.org.au/content/speech/murray-darling-coorong [extract of speech below]

.

.

[Speech by Rachel Siewert MP, The Australian Greens,Thursday 19th June 2008, ^http://rachel-siewert.greensmps.org.au/content/speech/murray-darling-coorong]

.

“I rise to speak to the motion to take note of the response of the Minister for Climate Change and Water, Senator Wong, representing the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts, to a question relating to the Murray-Darling river system. Today we had yet another report released on the health of the Murray.

It should come as no surprise, to those of us in particular who have been watching the Murray, that it finds that only one of 23 river valleys of the Murray that were examined had good ecosystem health. Two had moderate ecosystem health. All the rest-that is 20-had poor or very poor ecosystem health. This comes on the back of the report that was released yesterday-well, it was not released; it was leak-released.

On ABC radio the CEO of the Murray-Darling Basin Commission, Wendy Craik, said that the report had not ‘not been released‘; it just had not been released. That report, which had not been released but was not leaked, showed that scientists have said to the government that the Coorong has six months left. They have a six-month window of opportunity, and what is the ministerial council’s response? ‘Oh, we’ll commission some more work into that.’ That just happens to then be available in November. The window of opportunity to fix the Coorong, or to go to some measure to try to remediate the Coorong, closes in October.

.

The report that came out today shows yet again what a parlous state our Murray-Darling river system is in. And what is the government doing about it? Yes, it is buying some water and it is investing in fixing up infrastructure, but on a very ad hoc basis. It is like fiddling while Rome burns-‘We’ll set a new cap; we’ll put in place an authority, at some stage once we get the legislation back in, that will develop a plan for two years.’ But guess what? That plan does not come into effect until 2019. And the reason for that is that the federal government refuses to require New South Wales and Victoria to bring their water sharing plans into line with the basin, into line with the sustainable cap.

That means we will have a lovely plan, we will have planned very well, while the river is dying-because, unless we can curb water use and put into place sustainable water use in the extremely near future, we are going to be watching the river die. We will have a great plan but we will have no water to put back into the river because we are not requiring the states to implement any changes to their plans until 2019. That means no action until 2019, aside from what the government might be able to buy back from willing sellers. It does not do anything about addressing, with a systematic and strategic approach, long-term land use in the Murray-Darling Basin. It does not address what we think is going to be sustainable, not only in trying to address a severely degraded system but also in the face of climate change.

.

The CSIRO reports that are gradually being released as the work is done in each catchment-excellent work, I should say-are showing, as Senator Wong correctly pointed out, that the catchments are facing very severe consequences from the impact of climate change. We have over-allocated all the systems in the Murray-Darling system and we need to be addressing that now, not leaving it for some time off in the future.

.

Some of the ways that we can start addressing the issues around the Coorong now are to start looking at releasing water from the Meningie Lakes, to start looking at accessing some of the water that is currently held in storage in northern New South Wales and to start talking to farmers about loaning water-which, I would suggest, could be repaid with some benefits to the farmers into the future. But one of the issues that I understand is complicating matters there is the control of the New South Wales government over water in the Meningie Lakes. They control the water under 460 gigalitres, and the Commonwealth then gets to have a say in anything above, I think, 660 gigalitres. Guess what? If the level is kept below 660 gigalitres, where the Commonwealth get to have a say, it is all up to New South Wales.

So New South Wales can theoretically keep allocating water from that storage to maintain a level below the amount that the Commonwealth gets to have a say in. And guess what? There is no water to release to the Murray and into the Coorong lakes. If we cannot solve this issue in the Commonwealth’s brave new world of management of the Murray-Darling Basin, there is no hope. We are absolutely in a crisis situation in the Coorong, and yet the Commonwealth is still sitting on its hands and cannot, it appears, get that water from New South Wales and actually do something to save their own icon.”

.

– end of article –

Tags: ANU, Chowilla, Coorong, ecosystem health, Meningie Lakes, Minister for Climate Change and Water, Murray-Darling, Murray-Darling Basin Commission, Productivity Commission, River Red Gums, The Wilderness Society, TWS

Posted in Murray Darling (AU), Threats from Farming | No Comments »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

August 17th, 2011

The following article was initially posted by Tigerquoll on 20090423 on CanDoBetter.net:

.

I have to pinch myself to realise this is 2009 and not 1959!

Vicforests’ logging arson to 600 year old Eucalyptus regnans in East Gippsland, Victoria, Australia, 20090423

http://www.lighterfootprints.org/2009/04/brown-mountain-destruction-complete.html Vicforests’ logging arson to 600 year old Eucalyptus regnans in East Gippsland, Victoria, Australia, 20090423

http://www.lighterfootprints.org/2009/04/brown-mountain-destruction-complete.html

This photo just in from the old growth forests of Brown Mountain in East Gippsland – home of remnant giant Australian natives dating up to 600 years old. This photo shows the Brown Mountain Massacre yesterday (23 April 2009) of these magnificent giants by VicForests on its celebrated World Forestry Day.

In 2006, the then Premier, Steve Bracks, made a promise to “protect all significant stands of old growth currently available for logging” (hollow words by a man of renouned indecision). The immense trees that have sheltered and raised hundreds of generations of owls and gliding possums are now being hacked down by VicForests.” [Source: Environment East Gippsland’s, ‘The Potoroo Review‘, Issue 196]

VicForests’ leadership inspiration, Warren Hodgson, must feel pround leaving such a legacy of heritage denial to future Gippslanders, Victorian and Australians. “Warren Hodgson has been involved in policy development at the highest level of the Victorian public sector and has previously led the Victorian Government efforts on Public Private Partnerships. He has a background in the manufacturing industry in New Zealand and in the provision of contract services to public and private sectors throughout the Asia-Pacific region.”

.

.

.

‘VicForests’ (from its website) presents its vision and values as:

.

Our vision:

“To be a leader in a sustainable Victorian timber industry.”

Our purpose:

“To build a responsible business that generates the best community value from the commercial management of Victoria’s State forests.”

Our values:

“Accountable – VicForests is accountable to the Victorian Government. Its actions and those of its employees must be consistent with relevant Government policy and priorities.”

Committed – “VicForests is committed to the fulfilment of its purpose and the achievement of its vision for the Victorian timber industry.”

Safe – “VicForests and its staff will manage safe workplaces for all staff and contractors, and are committed to continuous improvement in safety systems and outcomes, in accordance with its Occupational Health and Safety Policy.”

Customer focused – “VicForests will be responsive to its customers’ requirements and seek customer satisfaction, in accordance with its commercial nature.”

Ethical – “VicForests will operate in an ethical and environmentally responsible manner in all its undertakings to ensure the integrity and sustainability of the native forest timber industry in Victoria.”

Innovative – “VicForests seeks to be innovative and adaptable in its organisational, business and forestry management operations.”

Open – “VicForests will manage the commercial harvesting and sale of timber in a framework of openness and transparency.”

Professional – “VicForests and its staff will operate in a professional manner in all undertakings to ensure the best possible outcomes for the organisation, its customers, the Victorian timber industry and its stakeholders.”

Sustainable – “VicForests will pursue the highest standards for forest management practices through the continued development of its Sustainable Forest Management System and by ensuring its triple bottom line performance against the requirements of Victoria’s Sustainability Charter for State forests.”

[SOURCE: http://www.vicforests.com.au/vision-purpose-and-values.htm]

.

.

I have to pinch myself to realise this is 2009 and not 1959!

.

.

.

Brown Mountain – destruction complete!

.

An urgent message from Jill Redwood of Environment East Gippsland (from 20090424). . .

“These were taken yesterday – VicForests mission accomplished.

This ancient stand of 600(plus) year old forest has now been fully annihilated and ready for conversion to a palm-oil plantation. Or it might as well be.

They’ll actually be converted to a pulpwood plantation for the Japanese paper industry.

The other four remaining stands of old growth adjoining are on the logging schedule.

Please help in whatever way you can.”

~ Jill [Environment East Gippsland]

.

.

.

Read More:

.

[1] ^http://www.greenlivingpedia.org/Brown_Mountain_old_growth_forest

[2] ^http://www.eastgippsland.net.au/

[3] ^http://www.eastgippsland.net.au/?q=campaigns/brown_mountain

.

– end of article –

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

August 9th, 2011

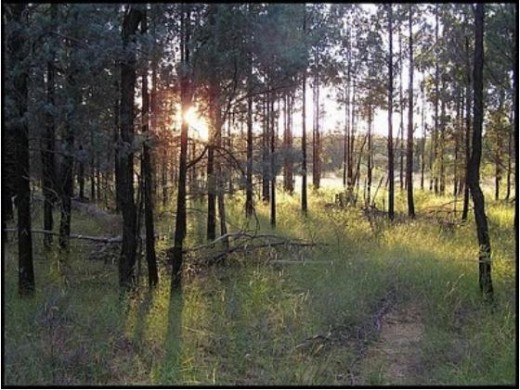

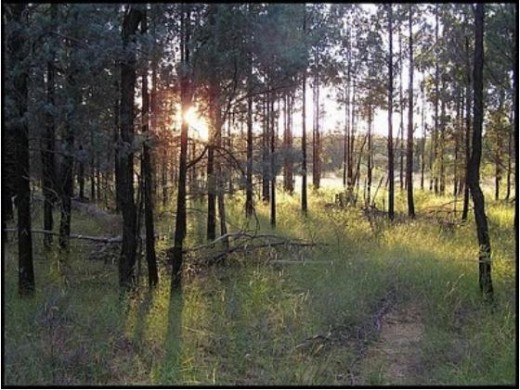

Pilliga Forest

The early morning sun illuminates fresh forest grasses

beneath a stand of young native White Cypress Pine (Callitris glaucophylla), Feb 2010

^http://huntervalleyjournal.blogspot.com/2010_02_01_archive.html Pilliga Forest

The early morning sun illuminates fresh forest grasses

beneath a stand of young native White Cypress Pine (Callitris glaucophylla), Feb 2010

^http://huntervalleyjournal.blogspot.com/2010_02_01_archive.html

.

The Pilliga Forests

.

‘The Pilliga‘, also traditionally known as ‘The Pilliga Scrub‘ is a vast western woodland – the largest continuous remnant of semi-arid woodland in temperate New South Wales, Australia. The Pilliga comprises the largest remaining area of native forest west of the Great Dividing Range, covering about 500,000 hectares between the Namoi River in the North and Warrumbungle Ranges in the South. The Pilliga is part of the Brigalow Belt South bioregion. Australian land mass is divided into 85 bioregions. Each bioregion is a large geographically distinct area of similar climate, geology, landform, vegetation and animal communities. [Read More]

The Pilliga is characterised by native white cypress and iron bark forests, broom bush plains, vivid spring flowers and abundant fauna. The forest contains at least 300 native animal species, with at least 22 endangered animal species including such favorites as the Glossy Black-Cockatoo, Squirrel Glider, Koala, Pilliga Mouse (Pseudomys pilligaensis) and Rufous Bettong, and at least 900 plant species including species now widely grown in cultivation as well as many threatened plant species. The forest spans about 3,000 square kilometres of land. Some towns that surround the forest include Narrabri, Pilliga, Gwabegar, Baradine, Coonabarabran, Boggabri and Baan Baa. Some areas of the forest, particularly in the Western Pilliga, are completely dominated by “cypress pine” (Callitris spp.), however there are a vast number of distinct plant communities in the forest, some of which do not include Callitris pine. Another dominant sub-canopy genus are the Casuarinas, while Eucalypts dominate the canopy throughout the forest. Much of the area is State Forest under the management of the New South Wales Government, which effectively means that it is unprotected.

The name ‘Pilliga’ (or ‘Billarga‘) is an Aboriginal word meaning swamp oak (Casuarina trees). The name was borrowed back in the mid 1800’s as the name of one of the original grazing runs, near where the town of Pilliga now stands. [This theory is contracted by Les Murray in his Forward in Eric Rolls‘ seminal 1981 book ‘A Million Wild Acres‘, who accounts at page iv…”the Pilliga (from Kamilaroi peelaka, a spearhead”).

The geology of the area is dominated by the Pilliga Sandstone, a coarse red/yellow Jurassic sandstone containing about 75% quartz, 15% plagioclase and 10% iron oxide,[2] although local variations in soil type do occur. Sandstone outcrops with basalt-capped ridges are common in the south, while the Pilliga outwash areas to the north and west are dominated by alluvial sediment from the sandy, flooding creeks.

Nuable Creek in flood, Pilliga 2004

Source: David Brodrick, 2004, ^http://www.narrabriweather.net/events/10Dec2004.html Nuable Creek in flood, Pilliga 2004

Source: David Brodrick, 2004, ^http://www.narrabriweather.net/events/10Dec2004.html

.

There is a vast network of roads throughout the scrub, many of which are former forestry roads. The forest once supported a large forestry industry in the surrounding towns (harvesting mostly cypress pine and ironbarks) however this has been greatly scaled back since 2005 when much of the forest was set aside for environmental conservation by the NSW government.

[Sources: ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pilliga_forest, ^ http://narrabri.net/Document1.aspx?id=1872]

According to the Narrabri Shire Visitor Information Centre, the Pilliga Forest… ‘is one of the largest native cypress forests in Australia and hosts an abundance of wildlife including koalas, kangaroos, possums, echidnas, goannas, emus and its very own species of mouse, the Pilliga Mouse. The area is renowned for its glorious wildflowers which can be found in the Forest year round, with particularly impressive displays in Spring. The Baradine Community has developed three wildflower routes through the Forest. The “Wildflowers of Baradine and the Pilliga’.

[Source: ^ http://www.visitnarrabri.cfm.predelegation.com/index.cfm?page_id=1051&page_name=Wildflowers%20in%20the%20Pilliga]

.

.

.

‘The Pilliga’..after rain

.

‘Prolific rain on the northwest plains of New South Wales

quickly results in a swelling of rivers and creeks,

followed by a profusion of growth and renewal.

.

Many centimetres of very welcome rain covered the black soil grazing pastures and agricultural properties

surrounding the village of Baradine over the first weekend of February, 2010.

We were there to witness this amazing natural event.

Sheets of water rapidly cover the vast plains,

draining into gullies and creeks, and filling rivers.

Many outlying unsealed roads become impassable,

and the town is temporarily isolated.

But life goes on with relative normality,

albeit with joyous appreciation of the blessings the downpour will bring.’

[Source: HunterValleyJournal, http://huntervalleyjournal.blogspot.com/2010_02_01_archive.html, Feb. 2010,]

.

.

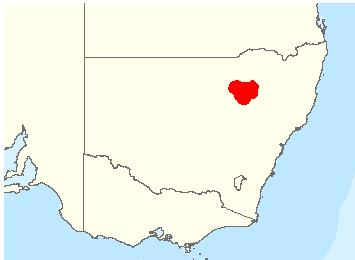

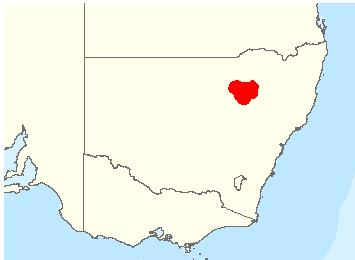

Where is ‘The Pilliga’?

Location of ‘The Pilliga’ as shown by the distribution map of the native Pilliga Mouse

Australian Department of Environment et al.

[Source: ^http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=99#recovery_plan_loop] Location of ‘The Pilliga’ as shown by the distribution map of the native Pilliga Mouse

Australian Department of Environment et al.

[Source: ^http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=99#recovery_plan_loop]

.

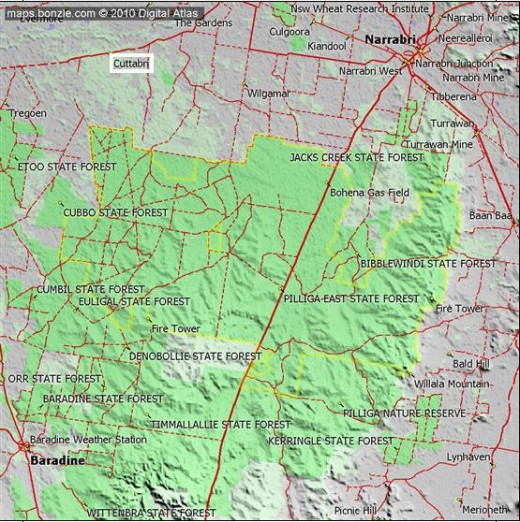

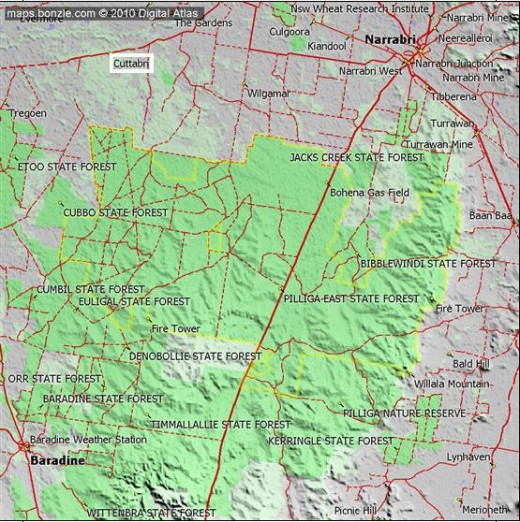

The Pilliga Forests

lie between the towns of Coonabrabran in the south and Narrabri in the north

situated in north western New South Wales in the Brigalow Belt South bioregion.

[Source: ^http://maps.bonzle.com/c/a?a=p&p=56925&cmd=sp] The Pilliga Forests

lie between the towns of Coonabrabran in the south and Narrabri in the north

situated in north western New South Wales in the Brigalow Belt South bioregion.

[Source: ^http://maps.bonzle.com/c/a?a=p&p=56925&cmd=sp]

.

.

The Pilliga’s history of colonial exploitation

.

‘Following many thousands of years of Aboriginal occupation, European settlers started arriving around the early 1830’s. These settlers established grazing runs throughout the forests, which then comprised a few well-scattered large trees over a grassy understorey. Aboriginal burning and grazing by Kangaroo Rats had kept the forest floor clear of regeneration until that time.

The introduction of cattle and sheep resulted in significant ecological changes. The soils deteriorated and the mix (and grazing quality) of the native grasses changed. The Kangaroo rats were displaced. The 1970’s and 1880’s produced a prolonged drought that saw most of the grazing runs abandoned. Then, during the late 1880’s and early 1890’s, there was a succession of good seasons and, in the absence of grazing pressure and regular burning; massive regeneration of native cypress and eucalyptus took place across much of the Pilliga.

The spread of rabbits to the area in the early 1900’s prevented any further regeneration events in the Pilliga until the introduction of myxomatosis in the 1950’s. With the demise of the Rabbit, a new pulse of young cypress and eucalypt seedlings was able to get up and away.

The cypress regeneration from the late 1800’s forms the basis of the timber industry operating from the Pilliga today. The 1950’s and subsequent growth is being managed to provide a sustainable supply of timber to industry for generations to come. In 1999, there were over 150 jobs dependant on the timber resources of the Pilliga and the industry provides the backbone of many small communities on the fringe of the Pilliga.

Wooleybah Sawmill, Pillaga

(NSW Heritage Office) Wooleybah Sawmill, Pillaga

(NSW Heritage Office)

.

Between the 1920’s and mid 1990’s, over 5 million railway sleepers were cut from ironbark grown in the Pilliga.

Ironbark is still used to produce fence posts and drops for electric fencing systems, where the non-conductivity of its heartwood provides a unique advantage.’ [Source: ^http://narrabri.net/Document1.aspx?id=1872]

The Pilliga is susceptible to bushfire – by lighting, arsonists and incompetence.

[Source: clubr8255’s photostream, http://www.flickr.com/photos/32053650@N03/with/3038473001/ The Pilliga is susceptible to bushfire – by lighting, arsonists and incompetence.

[Source: clubr8255’s photostream, http://www.flickr.com/photos/32053650@N03/with/3038473001/

.

.

The endemic ‘Pilliga Mouse’

‘Endemic‘ means found naturally nowhere else on the planet.

The Pilliga Mouse (Pseudomys pilligaensis ) is a small native murid rodent found in the Pilliga Forests ecosystem. It is listed as Vulnerable in Australia and is endemic to the Pilliga Forests of New South Wales.

The Pilliga Mouse is very sparsely distributed and appears to prefer moist gullies, areas dominated by extensive coverage of low grasses and sedges, broombush and areas containing an understorey of kurricabah (Acacia burrowii) with a bloodwood (Corymbia trachyphloia) overstorey. It is nocturnal and appears to live in burrows.

Its main threats are from logging operations that destroy the understorey particularly broombush, inappropriate fire regimes (broadscale and frequent bushfire management), predation by ferals (foxes, cats and wild pigs/boars)

.

[Source: ^http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=99]

.

.

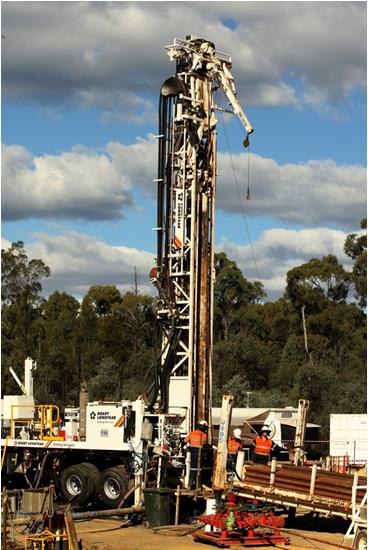

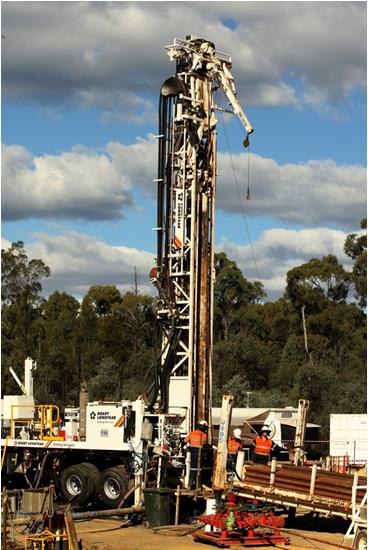

The Pilliga… now threatened by Mining

‘Eastern Star Gas coal seam expansion in Pilliga under federal investigation’

(Article on ABC Rural, 20110721, ^http://www.abc.net.au/rural/news/content/201107/s3274633.htm]

.

The Federal Government is investigating whether Eastern Star Gas is in breach of the Environment Protection Biodiversity Conseration Act at its coal seam gas project in NSW’s Pilliga forest.

The project is expected to result in the first large-scale coal seam gas operation in NSW. The Pilliga forest is the largest remaining temperate woodland in eastern Australia.

Chief Executive Officer of the National Conservation Council, Pepe Clark is calling on Santos, which owns Eastern Star Gas, to either desist or defer work until they have Federal approval.

A Silhouette of Pillage

Eastern Star Gas’s coal seam gas development in the Pilliga State Forest, A Silhouette of Pillage

Eastern Star Gas’s coal seam gas development in the Pilliga State Forest,

which is having a profound effect on the Bohema creek water quality and flow which flows into the Murray River

© The Wilderness Society, Photo by Dean Sewell, May 2011

.

.

‘Pilliga coal seam gas developments breach Federal environmental law: report’

(Article by Nature Conservation Council of NSW, 20110719, ^http://www.nccnsw.org.au/media/pilliga-coal-seam-gas-developments-breach-federal-environmental-law-report)

.

‘Eastern Star Gas has conducted coal seam gas exploration and production activities in the Pilliga forest without seeking federal assessment on matters of national environmental significance, according to a report by the Northern Inland Council for the Environment, The Wilderness Society and the Nature Conservation Council of NSW.

The report, Under the Radar, was released today following the recent purchase of Eastern Star Gas by one of Australia’s largest domestic gas producers, Santos.

“Eastern Star Gas has undertaken extensive coal seam gas exploration and production without seeking federal approval. This is likely to have damaged the habitat of iconic threatened species such as the Pilliga Mouse and the Regent Honeyeater,” said Warrick Jordan, Campaign Manager at the Wilderness Society Newcastle.

“Santos is taking on the most environmentally destructive and contentious gas project in NSW. As the new owner, Santos should look carefully at the damaging impacts of this proposal and immediately desist or refer all existing operations in the Pilliga for proper assessment.

“We are asking Tony Burke to immediately ‘call-in’ all existing Eastern Star Gas operations in the Pilliga under federal environment laws. Eastern Star should not be able to get away with destroying our natural heritage,” he said.

The Under the Radar report found coal seam gas operations in the Pilliga have cleared more than 150ha and fragmented 1,700ha of bushland, drilled 92 coal seam gas wells, constructed 56.6km of pipelines, and operated 35 production wells without seeking approval under the Federal EPBC Act. These activities have occurred in habitat for federally-listed threatened species, such as the South-Eastern Long-eared Bat.

“Under Commonwealth legislation, any potential impacts on nationally-threatened species must be referred to the Environment Department for approval. Eastern Star Gas has been flying under the radar to avoid this process in the Pilliga,” said Pepe Clarke, CEO of the Nature Conservation Council of NSW.

“Eastern Star has recently applied for Commonwealth approval for a large new coal seam gas field in the same area of the Pilliga as existing operations. If these future operations trigger federal environment laws, then so do the existing operations and Santos should immediately cease those operations and be refer them to the Federal Government”,” he said.

“The question remains, will Santos continue Eastern Star’s reckless attempts to turn the iconic Pilliga Forest into an industrial coal seam gas field? If Santos can’t be trusted to abide by environmental laws now, they cannot be trusted to manage the environmental impacts of NSW’ biggest coal seam gas development,” said Carmel Flint, of the Northern Inland Council for the Environment.

Under the Radar report summary

The Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) makes it illegal to undertake an activity that has, or is likely to have, a significant impact on matters of national environment significance. These prohibitions are set down in Part 3 of the EPBC Act 1999, in s18 and s20 respectively.

There are at least 24 matters of national environmental significance, as defined by the EPBC Act, which occur within the Pilliga Forest section of the Eastern Star Gas Petroleum Exploration Licence 238 and Petroleum Assessment Lease 2. These include known, likely, and potential habitat for 15 nationally threatened species (4 endangered, 11 vulnerable), and known or potential habitat for 9 migratory birds listed under international conventions.

Environment groups have conducted a detailed assessment of the likely impacts of current coal seam gas activities in the Pilliga Forest on matters of national environmental significance, by applying the Guidelines for Significant Impact set down by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC). These are the same guidelines that should have been applied by Eastern Star Gas to assess the impacts of the activities.

The following coal seam gas activities have been undertaken in PEL 238 and PAL2:

1. The drilling and on-going management of more than 92 coal seam gas bores and coreholes

2. The conduct of 482km of seismic surveys

3. The construction and management of 56.6km of gas and water gathering pipelines

4. The development and management of five production fields, encompassing 35 production bores

5. The construction and management of a gas-fired power station at Wilga Park, including an upgrade of the station from 10MW to 40MW

6. The construction and operation of 1 reverse osmosis unit

7. The construction and management of 13 major water treatment dams/impoundments and numerous drill ponds

8. The discharge of treated produced water into the Bohena Ck, part of the Murray-Darling Basin.

9. The bull-dozing of numerous roads and tracks to facilitate the construction and operation of works listed above.

None of these activities, nor the whole action combined, has ever been referred to the Federal Government for consideration of the likely impacts on federally-listed species under the EPBC Act 1999. There is no Federal approval in place for the action.

The environmental impacts of these activities include: direct destruction of at least 150ha of native vegetation that is habitat for federally-listed species; heavy fragmentation of an area of 1,700 ha of native vegetation leading to the spread of invasive species; creation of artificial watering points at more than 13 different locations representing a risk to wildlife; introducing numerous sources of pollution through the use of chemicals and the handling and disposal of produced water; direct alteration of the ecology of a creek system for up to 22km; increased fire ignition sources and introduction of a flammable gas into an already fire prone environment; an overall disturbance footprint across 44,700ha of bushland.

Applying the Guidelines for Significant Impact, the report concludes that the impacts on federally-listed species are likely to be significant because of the intensity at which they have occurred, as well as:

- The extraordinary national and international conservation significance of the environment in which it is occurring;

- The sensitivity of the ecosystem given the scale of extinctions that have already occurred in the mammal fauna and the scale of decline now evident in the bird fauna;

- The substantial geographic area affected;

- The high cumulative impact in the context of other threats (other mining and gas developments, background clearing rates, climate change, invasive species, logging, and high intensity and frequent fires);

- The low level of confidence with which the impacts are understood; and

- the context in which it occurs of a heavily cleared and highly fragmented landscape with very low levels of reservation.

- The measures put in place by Eastern Star Gas to avoid or mitigate impacts are inadequate to prevent such impacts, and their effectiveness is uncertain and not scientifically established.

..

.

‘Farmers see threat in $900m Santos buyout’

(Article by Ben Cubby and Brian Robins, in Sydney Morning Herald, 20110719, ^http://www.smh.com.au/environment/farmers-see-threat-in-900m-santos-buyout-20110718-1hlq7.html)

.

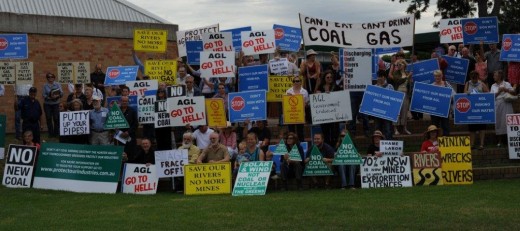

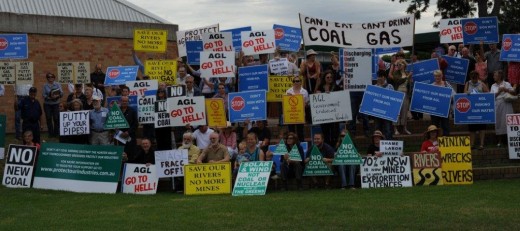

‘A GAS exploration company chaired by the former deputy prime minister John Anderson will be bought out for $900 million, in a move expected to pave the way for the first large-scale coal seam gas drilling operation in NSW.

The resources giant Santos will buy Mr Anderson’s Eastern Star Gas, which has plans to drill more than 500 gas wells in the Pilliga scrub, near Narrabri, the largest surviving remnant of temperate woodland in eastern Australia.

The plan has already sparked fierce resistance from some farmers, who have said they will lock their gates rather than allow drilling rigs on their grazing land. Many are concerned that the controversial fracking technique, which can lead to groundwater contamination, will be used.

Santos said it recognised the objections people had to coal seam gas drilling, and would campaign to win public support.

”We are confident these issues can be addressed,” said the chief executive, David Knox. ”We’re going to set the right pace and bring [the community] along, as we prove things up … We recognise the criticality of working with local communities.”

Last month Santos launched a television advertising campaign, saying that coal seam gas was ”a fuel for the future” and that the company had previously forged good relationships with rural land-holders.

Mr Knox said the federal government’s introduction of a carbon price would increase demand for gas instead of coal, which generally had higher greenhouse gas emissions.

The acquisition will make Santos the state’s biggest holder of coal seam gasfields.

Opponents say the construction of hundreds of wells, and a network of roads linking them, would industrialise the landscape. ”What’s being allowed here is an uncontrolled experiment on the Australian environment,” said Drew Hutton, a campaigner with the anti-coal seam gas group Lock the Gate Alliance.

Initial surveys prepared for Eastern Star indicate the area is home to many threatened animal and plant species, including the Pilliga mouse, black-striped wallaby, glossy black cockatoo, painted honeyeater and barking owl.

From the beginning of June the Moree Plains Shire Council has placed a 60-day moratorium on seismic surveys, drilling or exploration for coal seam gas, to allow the council and community time to study the implications of proposals.

A report produced by the Wilderness Society said the project was of national significance and should be independently assessed by the federal Environment Minister, Tony Burke.

“The Pilliga project, if it proceeds, will have a devastating impact on the environment,” said a Wilderness Society campaigner, Warrick Jordan.

”It will clear 2410 hectares of valuable bushland across the eastern Pilliga, including in a state conservation area, pose risks to the Great Artesian Basin, produce massive amounts of saline water, and the associated pipelines and wells will impact surrounding agricultural areas.”

The Nature Conservation Council of NSW also said that work already done on the site meant it should be referred to the federal government.

Tony Pickard, a farmer whose land falls within the proposed gas well area, said the first he had heard of the proposal was on a government website that showed dots on his land representing gas wells. Mr Pickard has vowed not to allow drilling on his land.

A NSW Greens MP, Jeremy Buckingham, is travelling through the state speaking to people who oppose coal seam gas extraction.

”To have an energy giant like Santos move in and take over means that the project is much more likely to go ahead,” Mr Buckingham said.

Santos footprints in The Pilliga Santos footprints in The Pilliga

.

‘Under the Radar – new report lifts the lid on Eastern Star Gas operations’

– Article by The Wilderness Society, [Source: ^http://www.wilderness.org.au/campaigns/coal-seam-gas/under-the-radar-new-report-lifts-the-lid-on-eastern-star-gas-operations]

.

‘Eastern Star Gas has been trashing parts of the Pilliga since 2004, avoiding environmental laws in the process. A new report by the Wilderness Society, the Northern Inland Council for the Environment, and the Nature Conservation Council has exposed this scandal.

The Pilliga Forest is home to a host of threatened species, including the Pilliga Mouse and the Regent Honeyeater. Many of these species are listed under the federal Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

When a company wants to develop a project on a site with nationally listed threatened species, they are required by law to refer the project to the federal environment department.

Eastern Star Gas has been exploring for and producing coal seam gas in the Pilliga Forest since 2004. This has resulted, amongst other actions, in the clearing of 150 hectares of forest, fragmentation of a further 1700 hectares, and the dumping of waste water into creeks.

The ‘Under the Radar‘ (1.35MB – pdf) report concludes that Eastern Star Gas has impacted threatened species habitat, and should have sought federal environmental assessment for its operations. All current and proposed activities should be suspended, and assessed by the Commonwealth Environment Department.

Eastern Star Gas, after ignoring environmental legislation, now wants to build the biggest coal seam gas project in NSW in the Pilliga. They promote this destructive project as environmentally friendly and well managed.

Eastern Star has been exposed as a company that will get away with what it can if it thinks no-one is looking.

Well, now we are watching, and we’ll be ensuring, with your help, that the unique Pilliga Forest won’t become an industrial wasteland.’

.

.

‘A national treasure or an industrial wasteland?’

– Article by Carmel Flint in the Colong Bulletin, No. 241, July 2011, pp.1-2, reproduced with premission of The Colong Foundation for Wilderness, Inc.

.

Coal seam gas has recently emerged as a massive threat to the future of the Pilliga Forest, in north-west NSW. The Pilliga is located between Narrabri and Coonabarabran, and covers an extraordinary 500,000 hectares of intact and contiguous bushland.

The Bibblewindi water pollution ponds are one of ten constructed during the Pilliga ‘exploration’ phase.

So far there are 1,100 well heads planned for gas extraction just in the eastern quarter of the Pilliga alone.

Photo: T Pickard The Bibblewindi water pollution ponds are one of ten constructed during the Pilliga ‘exploration’ phase.

So far there are 1,100 well heads planned for gas extraction just in the eastern quarter of the Pilliga alone.

Photo: T Pickard

One tends to run out of superlatives very quickly when it comes to the conservation significance of the Pilliga.

It is the largest temperate woodland left in eastern Australia and the southern recharge area for the Great Artesian Basin. It’s surface waters flow into the rivers of the Murray-Darling Basin. It is the single most important biodiversity refuge area remaining in the NSW Wheat-Sheep Belt.

The Pilliga is home to more than 25 threatened or migratory species that are listed under federal laws and at least 48 threatened species under NSW law. It includes the only known population of the endemic Pilliga Mouse, the largest Koala population in western NSW and the only known Black-striped Wallaby population in western NSW. It represents the national stronghold for populations of the Barking Owl and the Southeastern Long-eared Bat within eastern Australia.

It is an internationally recognised Important Bird Area, with particular significance for the Painted Honeyeater and Diamond Firetail. It is also recognised as an important part of the East Australian Bird Migration System, and is located in the Brigalow Belt South bioregion which is one of only 15 biodiversity hotspots recognised by the Federal Government across the nation. It is mostly public land, either State Forest, State Conservation Area or National Park, and it has recognised wilderness values.

Coal seam gas companies have been conducting exploration in the Pilliga for about 10 years now, and they have already done considerable damage. Under the guise of exploration, they have to date drilled 92 coal seam gas wells, constructed 46.2km of pipelines, conducted 394.2km of seismic surveys, constructed 1 gas compression station and 1 reverse osmosis unit, developed five pilot production fields encompassing 35 boreholes, produced and delivered gas to a local power station, constructed

10 major water treatment dams/impoundments, discharged produced water into a local creek system and bulldozed numerous roads and tracks. This, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. In April this year Eastern Star Gas applied to the Federal Government for

an environmental approval to move to full production in the Pilliga Forest.

They want to put in 1,100 wellheads and 1,000km of pipelines across the eastern section of the Pilliga, clearing at least 2,410 hectares and fragmenting 85,000 hectares.

.

Associated with this proposal are two pipelines – one to a proposed gas-fired power station at Wellington and another to a proposed new LNG export facility at Newcastle. By incorporating the first ever major LNG export facility, this Pilliga proposal will effectively open up the whole state to a massive expansion in coal seam gas. And, if that is not enough, it is very clear that this is only the beginning of the project. Having reviewed the data on coal seam gas potential across the companies full exploration licence (PEL238) we estimate that they will ultimately drill 7,100 boreholes, develop 7,000km of pipeline and clear more than 8,000 hectares of land across the Pilliga Forest and farmlands to the north.

Coal seam gas will destroy, fragment and degrade the integrity of this natural treasure. It will transform a thriving, living ecosystem into a heavy industrial zone with massive impacts on fauna and flora. It will dramatically increase fire risk and forever

change the nature of this wildflower wonderland.

.

If you don’t accept such an appalling transformation, then please act now to do something about it.

Email carmelflint@tpg.com.au to get involved and keep updated on what you can do.

.

.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘Under the Radar: How Coal Seam Gas Mining in the Pilliga is impacting matters of national environmental significance‘, 201106, a joint publication by The Wilderness Society Newcastle, The Nature Conservation Council of NSW and Northern Inland Council for the Environment. [>Open PDF document]

[2] ^http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pilliga_forest,

[3] ^http://narrabri.net/Document1.aspx?id=1872

[4] ^http://huntervalleyjournal.blogspot.com/2010_02_01_archive.html

[5] ^http://www.nccnsw.org.au/media/pilliga-coal-seam-gas-developments-breach-federal-environmental-law-report

[6] ‘A Million Wild Acres’, 1981, by Eric Rolls, $32.95, GHR Press, ^http://ghrpress.com/shoppingcart/index.php?main_page=product_info&products_id=7

.

‘Thirty years ago, a bomb landed in the field of Australian consciousness of itself and its land in the form of Eric Rolls’ A Million Wild Acres. The ensuing explosion has caused extensive and heated debate ever since amongst historians, ecologists, environmentalists, poets and writers. Now reprinted in a commemorative 30th Anniversary Edition for a new generation of readers and against the backdrop of renewed and urgent concern about climate change, it includes Tom Griffiths’ seminal essay, The Writing of A Million Wild Acres, and a foreword by Les Murray drawn from his work Eric Rolls and the Golden Disobedience.

Here is a contentious story of men and their passion for land; of occupation and settlement; of destruction and growth. By following the tracks of these pioneers who crossed the Blue Mountains into northern New South Wales, Eric Rolls – poet, farmer and self-taught naturalist – has written the history of European settlement in Australia. He evokes the ruthlessness and determination of the first settlers who worked the land — a land they knew little about.

Rolls has re-written the history of settlement and destroyed the argument that Australia’s present dense eucalypt forests are the remnants of 200 years of energetic clearing.

Neither education nor social advantage decided the success of the first settlers, or those squatters, selectors, stockmen and timber getters who helped grow the Pilliga forest. Few men were more violent than John Macarthur, few rogues more vigorous than William Cox, few statesmen more self-seeking than William Wentworth.

Rolls’ environment teems with wildlife, with plants and trees, with feral pigs; with the marvellous interaction of insects and plants, rare animals and birds. The lovely tangle which is the modern forest comes to life as Rolls reflects on soils, living conditions, breeding and ecology.

Winner of the prestigious Age Book of the Year Award, A Million Wild Acres is also an important account of the long-term effect man – both black and white – has had upon the forest.’

“The story of the Pilliga forest is one of advance, disappointment and retreat by pastoralists and then by small farmers“. [Les Murray]

May Santos and its Eastern Star Gas venture follow suit and show The Pilliga the respect it so long deserves.

.

.

.

Related Reading:

.

[1] Wollembi Valley Against Gas Extraction,

^http://wage.org.au/news/

.

.

[2] The Permaculture Research Institute of Australia, ‘Save Pilliga – NSW’s Largest Temperate Woodland’,

^http://permaculture.org.au/2011/05/25/save-pilliga-nsws-largest-temperate-woodland/

‘Save Pilliga – NSW’s Largest Temperate Woodland’

— by Cate Faehrmann May 25, 2011

Introduction

Eastern Star Gas has applied for approval under both state and federal regulations to develop a massive coal seam gas field of around 550 gas wells in the State Forests of The Pilliga. Commonly known as the ‘Pilliga Scrub’, this unique woodland is near Narrabri in northern NSW. The gas project is set to clear over 2,400 hectares of native vegetation and will forever change the landscape of the Pilliga.

The Pilliga Scrub is a highly significant area in terms of the state’s biodiversity. It is known to be the largest continuous remnant of semi-arid woodland in temperate New South Wales and contains many threatened animal and plant species such as the Pilliga Mouse, Black-striped Wallaby and South-eastern Long-eared Bat.

Email the Minister now and ask him to protect the Pilliga Scrub from coal seam gas.

Black-striped Wallaby, a mostly nocturnal animal under threat from land clearing, and now, coal seam gas.

The gas field and the related infrastructure proposals (including two major regional pipelines) have been determined to be ‘controlled actions’ under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. This means they will require the approval of Minister Tony Burke and the Federal Department of Environment. There is also a proposal from Eastern Star Gas being referred for a LNG export processing facility at Kooragang Island at Newcastle.

At the NSW Government level, the projects are being assessed by the Department of Planning under Part3A. The Director General’s Requirements (DGRs) for the environmental assessments were issued in December 2010, but this was not made public until after the recent state election. You can view them here.

This is the biggest coal seam gas field ever proposed in NSW and the first ever LNG export facility in the state. However, it looks to be just the beginning. Eastern Star Gas, headed by former Nationals Leader and Deputy Prime Minister John Anderson, has not revealed their full plans for the area. Coal seams extend underneath almost the entire Pilliga Scrub, and this initial proposal covers 85,000ha of a 500,000ha vegetation remnant. Extrapolating these figures, 550 wells now could mean as many as 3,000 wells in the future. You can read more about the EPBC referrals for the Narrabri Gas Field here at the Federal Environment Department’s website.

The four project components

- Development of a major coal seam gas field in the Pilliga Scrub

- A pipeline from Narrabri to Wellington (via Coolah)

- A pipeline from Coolah to Newcastle

- An LNG export facility at Kooragang Island at Newcastle

Existing activities

Eastern Star Gas Limited (ESG) is the operator of the Narrabri CSG Joint Venture (NJV). Some 35% of the CSG interest in PEL 238 is strata titled to Santos. The Chairman of ESG is John Anderson, former National Party politician. The Narrabri Coal Seam Gas Project is being developed by the NJV.

ESG developed the Wilga Park Power Station in 2004, and supplied it with gas from the Coonarah Gas Field on private land to the north of the Pilliga.

In 2006, a number of closely spaced well production pilots were developed in the Bohena and Bibblewindi fields in the Pilliga Scrub. In 2008, approval was granted for a gas pipeline from the pilot wells in the Pilliga to the Wilga Park Power Station and the expansion of the power station. The expected supply of gas from the Coonarah Gas fields did not eventuate, and the station has been utilising production gas from the pilot wells. The NJV currently has an MOU with ERM Power for the provision of gas to a new gas fired power station at Wellington over a 20 year period commencing in 2013.

Gas field development

The proposed gas field development area covers approximately 85,000 ha and includes Pilliga East State Forest, Bibblewindi State Forest, Jacks Creek State Forest, and Pilliga East State Conservation Area, plus some small areas of Crown Land and private land. The project aims to produce, process, compress and transport CSG from within Petroleum Exploration Licence 238, Petroleum Production Lease 3 and Petroleum Assessment Lease 2.

The project proposal includes the following:

- 550 production well sets, initially, on a 500m spacing

- 1,000 km of gas and water gathering systems (ie pipelines)

- access tracks (through the Pilliga Forests)

- a co-located gas processing and compression plant

- a centralised water management facility

- Ancillary infrastructure such as offices and workshops.

Impacts

The gas production will clear at least 2,410 hectares of native vegetation!

The area that is being targeted includes:

- A rich variety of heritage sites, including a rock shelter, burials, a grinding groove, scarred trees, open sites, stone artefact scatters and isolated finds.

- An Internationally recognised Important Bird Area.

- Known or likely habitat for 25 nationally listed threatened species and five nationally listed Endangered Ecological Communities.

- Known or likely habitat for 48 state-listed threatened species and five state-listed Endangered Ecological Communities including:

- Pilliga Mouse – known only from the Pilliga Scrub, this nationally vulnerable species has a total distribution of only 100,000 hectares. It will be severely impacted by the direct habitat loss, increased predation, and fragmentation leading to impacts on dispersal.

- Black-striped Wallaby – endangered in NSW, the northern Pilliga is the only known location of this species in western NSW. Requiring dense vegetation, it is extremely vulnerable to clearing, fragmentation and increased predation.

- Malleefowl – considered endangered in NSW and nationally vulnerable, has been recorded previously in eastern Pilliga. It is highly vulnerable to increased predation and fire.

- South-eastern Long-eared Bat – the Pilliga Scrub is recognised as the likely national stronghold for this vulnerable species (NSW and Federal). It prefers large, intact stands of native vegetation, and is at risk of fragmentation, loss of hollow trees, and uncovered saline ponds. Numerous other threatened bat species face similar risks from the proposal.

- Glossy Black Cockatoo – a very significant western population of the Glossy Black Cockatoo occurs in the Pilliga Scrub.

- Squirrel Glider, Koala and Eastern Pygmy Possum – which are all likely to be severely impacted by the direct habitat loss, fragmentation (and particularly its impacts on mobility and dispersal), and increased predation.

- Grey-crowned Babbler, Diamond Firetail, Hooded Robin, Speckled Warbler – and numerous other declining woodland birds for which the Pilliga represents a major refuge area. Those species are all threatened by increased fragmentation and predation.

- This area of the Pilliga Scrub is prone to severe, high intensity fires that burn very quickly through vast areas. The proposal to have a massive compressor facility located in the Pilliga, and 550 well production sets, represents a very serious fire risk and has the potential to render a regular Pilliga hot burn to a catastrophic level.

Water resources

The Eastern Star Gas proposal suggests that it intends to use lateral drilling rather than hydraulic fracturing (fracking), but it does not explicitly prohibit or rule it out. There is inadequate assessment of the impacts on groundwater and aquifers, including the Great Artesian Basin. The proposal is extremely vague as to what it plans to do with the water that is produced as a by-product of the extraction process. Currently it states that it will use “a combination of storage and evaporation with tertiary treatment and discharge (environmental flows) for co-produced water management”. Produced water contains a range of naturally occurring substances that are likely to be harmful to the environment and human health. It is highly saline, and can also contain toxic drilling and fracturing chemicals. Eastern Star Gas commits to the development of a Water Management Strategy, but in the absence of such a strategy it is not possible to assess the potential impacts on biodiversity or the environment of produced water.

Take action to save the Pilliga Scrub

The Pilliga campaign will no doubt be the next big fight to protect biodiversity in NSW. The coal seam gas industry is expanding rapidly, and governments are largely taking the advice of industry on the environmental impacts.

As a first step, please send a message to the Federal Environment Minister requesting he reject the project under the EPBC Act. You can write your own personal email by contacting him here. Or simply fill out the form here to send him a generic message.

As the Greens environment spokesperson, together with my colleague Jeremy Buckingham as the Greens mining spokesperson, we’ll be building a campaign to save the Pilliga from coal seam gas and to protect its unique biodiversity. Check back here soon for more information on how you can help save the Pilliga Scrub.

.

.

[3] Pilliga Nature Reserve

^http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/nationalparks/parkHome.aspx?id=N0464

.

.

[4] GreenLeft, ‘Pilliga Forest new CSG battlefront‘

^http://www.greenleft.org.au/node/47934

‘Pilliga forest new CSG battlefront’

By Kate Ausburn, 20110618

.

The Pilliga State Forest in northern NSW will be turned into a gas field if the government approves Eastern Star Gas‘s (ESG) mining proposal for the region. The proposal set out by ESG seeks to develop the Pilliga into the state’s largest coal seam gas (CSG) project.

The development would include the drilling of more than 1000 gas wells and the clearing of vast stretches of native bushland to make way for gas pipelines and other associated infrastructure, such as a water treatment facility and access roads. ESG is already carrying out smaller scale gas development in the Pilliga, as the operator of the Narrabri CSG Joint Venture.

In 2006, ESG developed coal seam gas production pilot wells in the Pilliga. A gas pipeline was also approved and built to carry gas from these wells to the Wilga Park Power Station, which was built by ESG in 2004.

As well as the wells now used to produce gas, some capped, unused gas wells remain behind barbed wire fences in cleared areas of the Pilliga. At least one expansive pond holding wastewater produced by coal seam gas extraction sits amassing algae on its surface.

ESG’s plans for large-scale expansion of coal seam gas operations in the Pilliga have been criticised by environmental groups and landowners from the region.

The Greens NSW environment spokesperson Cate Faehrmann explained the scale of ESG’s proposal: “The proposed gas field development area covers approximately 85,000 hectares and includes Pilliga East State Forest, Bibblewindi State Forest, Jacks Creek State Forest, and Pilliga East State Conservation Area, plus some small areas of Crown Land and private land.”

Despite the NSW government’s recent introduction of “transitional agreements” to regulate the expanding coal seam gas industry, ESG’s Managing Director David Casey is hopeful about the future of his company’s proposal for the Pilliga.

In a May 25 Open Briefing document, Casey said ESG continues to “monitor opportunities and development pathways with a view to ensuring early commercialisation of the project for the benefit of shareholders …

“Currently, our best estimate is that Federal and NSW regulatory approvals will be in place … in early 2012.”

However, The Wilderness Society’s Warrick Jordan said on June 16 that “given the scale of the project and current uncertainty over NSW mining and planning policy” ESG’s timeline would be difficult to fulfil.

“Estimates of state and federal approval being in place in six months appear wildly optimistic,” he said.

“The assessment requires full community consultation and proper consideration of environmental impacts on 85,000 hectares of forest, 1600 km of pipeline, a RAMSAR wetland, the marine environment, and the Great Artesian Basin.”

Local community and environmental groups came together on June 9 to tour the Pilliga and discuss campaigning strategy to minimise risks associated with coal seam gas and safeguard the environmental integrity of the region.

The coalition of groups will combine their efforts to campaign against expansion of coal seam gas mining in the Pilliga.

The Wilderness Society said on June 16:

“The project area in the Pilliga is a recharge area for the Great Artesian Basin and includes habitat for threatened species, endangered ecological communities, and an area protected under legislation for its natural values.”

.

.

Links to articles on the dangers of Fracking Coal Seam Gas:

.

[5] ^http://www.thegreenpages.com.au/news/fracking-coal-seam-gas-may-poison-organic-farms/

[6] ^http://ntn.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/NTN-CSG-Report-July-2011.pdf

[7] ^http://www.envirowiki.info/Coal_seam_gas

[8] ^http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/environment/energy-smart/origin-stops-coal-seam-gas-drilling-after-chemicals-found-in-water-20101020-16ud7.html

[9] ^http://www.perthnow.com.au/news/special-features/fracking-threatens-wa-water-resources/story-e6frg19l-1226010221897

[10] ^http://lockthegate.org.au/csg-facts/csg-factsheet.cfm

[11] ^http://dea.org.au/news/article/fracking_for_coal_gas_is_a_health_hazard

[12] ^http://theconversation.edu.au/coal-seam-gas-could-be-a-fracking-disaster-for-our-health-1493

.

.

.

Community Solidarity:

.

The Coal Seam Gas industry is selfishly exploiting Australian resources for corporate profit, much of which is channelled to foreign owners and investors offshore. In the process, coal seam gas exploration, drilling, fracking and the carcinogenic B-TEX chemicals used are destroying Australia’s natural environment and arable land – bulldozing habitat and spewing salt above ground, while below ground chemically poisoning Australia’s Great Artesian Basin and ground water. The industry is one of extreme discretionary greed and arrogance, perpetuating local environmental rape, pillage and plunder.

If you think your area is the only one concerned about coal seem gas , think again.

The following communities around Australia are being exploited by coal seam gas corporations:

-

Camden, NSW

-

Helensburgh and the Illawarra, NSW

-

Pilliga, NSW

-

Liverpool Plains, NSW

-

Wellington, NSW

-

Gunnedah Basin, NSW

-

Gloucester, NSW

-

Broke, NSW

-

Wollombi, NSW

-

Northern Rivers, NSW

-

Cooper Plains, SA,

-

Otways, Vic

-

Tara, Qld

-

Cecil Plains, Qld

-

Darling Downs, Qld

.

Follow similar community campaigns at the following links:

.

[1] ^http://www.gabpg.org.au/downs-farmers-challenge-csg-water-claims

[2] ^http://stop-csg-illawarra.org/

[3] ^http://www.keerronggassquad.org/

[4] ^http://www.stopcoalseamgas.com/

[5] ^http://www.kateausburn.com/2011/07/05/first-for-nsw-protest-stops-coal-seam-gas-rig/

[6] ^http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/tara-residents-blockade-queensland-gas-company-to-stop-seismic-testing/story-e6freoof-1225903149452

[7] ^http://lockthegate.org.au/tara/

[8] ^http://huntervalleyprotectionalliance.com/

[9] ^http://macarthur-chronicle-camden.whereilive.com.au/news/story/insert-web-head-here-62/

[10] ^http://www.zimbio.com/Australia/articles/P4B7C9pLq7Y/STOP+GLOUCESTER+Coal+Seam+Gas+Mining+near

(The above websites were accessed 20110809)

.

-end of article –

Tags: A Million Wild Acres, a silhouette of pillage, AGL, Apex Energy NL, B-TEX, Bringalow Belt South, Eastern Star Gas, former deputy prime minister John Anderson, fracking coal seam gas, Origin Energy, Pilliga Coal Seam Gas, Pilliga Forests, Pilliga Mouse, Pilliga yowie, Queensland Gas Company, Santos, the Pilliga, what the frack

Posted in Mice (native) and Antechinus, Pilliga (AU), Threats from Bushfire, Threats from Colonising Species, Threats from Deforestation, Threats from Mining | No Comments »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

August 7th, 2011

The following article was initially posted Tigerquoll on CanDoBetter.net 20090422, and subsequently updated.

Logging a road through old-growth rainforest

Atherton Tablelands, Far North Queensland

© 2008 Friends of the Earth Kuranda

[Source http://foekuranda.org/]

Logging a road through old-growth rainforest

Atherton Tablelands, Far North Queensland

© 2008 Friends of the Earth Kuranda

[Source http://foekuranda.org/]

.

‘World Forestry Day’ on 21st March is a greenwash promotion by the logging industry. It has the same meaning as the oxymoronic ‘eco-logging‘ (see above photograph).

[‘Eco=logging‘ means that we do leave some trees, sometimes. Some dodgy entrepreneur in South America has tried to register the name ‘ecologging’ as a trademark [^Read More] ]

The concept sounds noble enough on the Victorian Government’s Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) site:

“World Forestry Day has been celebrated around the world for 30 years to remind communities of the importance of forests and the many benefits which we gain from them. The concept of having a World Forestry Day originated at the 23rd General Assembly of the European Confederation of Agriculture in 1971.”

.

But hang on a second!

…a “Confederation of Agriculture” …this suggests a different set of values than anecological respect for native forests; somewhat more to do with agriculture (aka ‘logging‘). But I let the Victorian Government’s Dept of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) site continue:

.

“Forests provide many valuable things for the whole community. These include fresh water from forested catchments, a safe home for our flora and fauna, timber for our homes, furniture and paper, beautiful scenery and rugged environments for those who enjoy the outdoors, pollen and nectar for honey production, and archaeological and historical sites.”

“Today, Victoria has an area of approximately 22.7 million hectares. About 40% is public land, meaning that it is owned by the State and managed by the government. There are about 4.8 million hectares of publicly owned native forest which is divided into the following categories: National parks and reserves – 1.7 million hectares, State forest – 3.1 million hectares.”

“Less than one third of Victoria’s state forests are available for timber harvesting and these forests produce more than two million cubic metres of wood products which return about $50 million in revenue to the State.”

.

Ah Ha! So it’s all about revenue FROM our native forests, not a about being FOR our native forests! That phrase ‘timber harvesting‘ conveys such wholesome overtones of good honest pastoral labour, except it’s bloody logging forests! The term has been borrowed by poachers slaughtering kangaroos who euphemistically label the wildlife crime as ‘kangaroo harvesting‘.

So why not just rename this green-washing ‘World Forestry Day‘ what it really is: a celebration of logging – and rename it ‘World Logging Day‘?

DSE on its site suggests:

‘What can I do on World Forestry Day?” ..well children (the propaganda targets school children):

“Celebrate World Forestry Day by visiting your local forests and learning more about the many contributions they make to our well-being. For further information and ideas, see our Forest Education Information.” This link then takes the children directly to the ‘For Schools;’ section of its website which sends a key mesage [sic] to students that ‘forests have many different uses and values.” A second link takes children direct to the hardcore logging site of the Department of Primary Industries”.

[SOURCE: ^http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/DSE/nrenfor.nsf/childdocs/-8E773CD126CA22704A256AA40000EDEE-034EBCC6B1670D984A256AA40011A9F8?open]

.

Proud logger Proud logger

.

Forests should be celebrated in their natural state, not by their exploitative revenue potential. Pity that we are now celebrating these in islands and outside the mainstream media. The contrasting ‘Earth Hour’ hype of late seems so token, yet attracts such mainstream publicity and has even Peter Garrett as its cheerleader! But beyond people thinking about turning off lights, Earth Hour pales in addressing irreversible planet damage compared with any day that recognizes the value of global forests.

Recognising natural undisturbed forests and the ‘green carbon’ benefits they contribute to a healthy global future is more important than token politics. As advocated by Professor Brendan Mackey in an article in EEG’s The Potoroo Review (current Spring/Summer 2008-09 edition, p9), “estimates that around 9.3 billion tones of carbon can be stored in the 14.5 million hectares of eucalypt forest in southeast Australia IF THEY ARE LEFT UNDISTURBED.”

While one supports the celebration of native forests in their natural place, the drawback of World Forestry Day is that the forestry industry has corrupted the word ‘forestry’ into a vernacular meaning of ‘exploitation value’.

.

.

World Forest Day – online propaganda during 2010

.

In 2010, if one searched ‘World Forestry Day’ online, one got the following suspicious results:

.

Google Search #1: Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) (aka Victorian Government)…say no more

http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/DSE/nrenfor.nsf/childdocs/-8E773CD126CA227 04A256AA40000EDE E-034EBCC6B1670D 984A256AA40011A9 F8?open

.

Search Result in 2011:

.

Google Search #2: NSW Department of Primary Industries | Forests (a chainsaw endorsed site)

http://www.forest.nsw.gov.au/publication/forest_facts/celebrating_ trees_forests/default.asp

.

Search Result in 2011:

.

Google Search #3: Global Education, but linked to ‘DSE’ after scrolling down the page

http://www.forest.nsw.gov.au/publication/forest_facts/celebrating_ trees_forests/default.asp4: Better Health Victoria

(another Victorian Government website)

.

Search Result in 2011:

.

Google Search #4: Better Health (Victorian Government again)

http://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcevent.nsf/pages/DF43C04B6CC6D19E CA257250007C8F46 ?opendocument

.

Search Result in 2011:

.

So when searching ‘World Forestry Day‘ online, clearly Australian state governments’ greenwashing has set up prime presence.

[Editor: The above government links have disappeared consistent with government short-termism].

.

.

NAFI Propaganda

.

Equally the National Association of Forestry Industries (NAFI) ^http://www.nafi.com.au offered a propaganda page on World Forest Day during 2011.

NAFI’s logo

NAFI’s logo

.

NAFI boasts that it is..

‘the peak forest industry body in Australia representing a wide variety of companies involved in forest management, wood processing, commercial tree plantation growing, timber sales and distribution, carbon offset growers, forestry harvesters, haulage contractors, and engineered wood products manufacturers. NAFI also represents the interests of forestry research bodies, timber community groups and state forest industry bodies.’

.

Not surprisingly NAFI is located within a ten minute drive of Parliament House Canberra, with a politician never out of earshot.

.

NAFI’s VISION THING

.

‘The vision of NAFI is for an ecologicaly [sic] sustainable Australian society based, in part, on a dynamic, internationally competitive forest industry.’

Clearly drafted by an expensive consultant, it is utopian in its desire for harmonious co-existence between making a buck from logging forests, and conserving the ecological values of those same forests. In other words having one’s cake and eating it too. Pity they couldn’t spell ‘ecologically’.

Yet, conspicuously, ‘ecologically sustainable’ is missing in NAFI’s Objectives.

.

NAFI’s OBJECTIVES

.

- Improve the commercial results and investment attractiveness of the forest industries through favourable government policy decision and actions (i.e. make money from logging).

- Create a preferred position for the Australian forest industries in the rapidly changing international framework of treaties, codes of practice, standards, conventions and legislation. (i.e. influence law making so that more money can be made from logging).

- Achieve widespread community recognition of the social, environmental and economic benefits of forest industries. (i.e. drive a propaganda strategy to win hearts and minds that logging is good).

- Support and promote innovation, research and development. (i.e. pay universities to write reports to show that logging is good).

- Improve market opportunities and competitive advantage in order to increase demand for forest products and achieve consumer satisfaction (i.e. market logging).

- Achieve maximum utilisation of Australian resources within a framework of an open and competitive market. (i.e. be efficient by logging all the forest and invite others to join in).

- Service members needs and maximise industry ownership and involvement in the Association. (i.e. lobby loggers interests for more forests to log and build numbers to maximise political influence)

.

Without compromise, the above objectives convey a single minded focus on commercial logging of forests.

.

NAFI’s BIGGER LOGGER LOBBY GROUPING: ‘AFPA’

.

Consistent with the NAFI objectives (not the VISION), in April 2011 the Australian Forest Products Association (AFPA) was formed through the merger of the Australian Plantations Products and Paper Industry Council (A3P) and the National Association of Forest Industries (NAFI). Nothing uncertain about the motives of this organisation. Anyone who profits from logging is represented by AFPA – ‘tree plantation growers, harvest and haulage contractors, sawmillers, forest product exporters, and pulp and paper processors’. The new website is ^http://www.ausfpa.com.au/site/

Not surprisingly, AFPA is strategically located in NAFI’s offices, just a ten minute drive from Parliament House, Canberra, with ready access to the hearts and minds of Australia’s federal politicians.

A few weeks prior on 21 March 2011, a gala dinner was staged between the loggers and the politicians up the road at Parliament House, Canberra to (believe it or not) celebrate the United Nations’ Declaration of 2011 as the ‘International Year of Forests’. The logger body’s response to 2011 being the ‘International Year of Forests’ has been to unite loggers into a single united mighty lobbying force for logging – the AFPA.

“A single voice, a single association, is a clearer and more concise way to present the forest products industry to governments, the media and the people of Australia in a united fashion.”

– Linda Sewell, transitional Chairperson of AFPA and A3P Chairperson, after announcing the creation of AFPA in Canberra on 21 March 2011.

No surprise who is on the Transitional Board of AFPA – loggers and logging product merchants one and all:

- Ms Linda Sewell, HVP Plantations (Transitional Chairperson)

- Mr Bryan Tisher, Boral Timbers (Transitional Treasurer)

- Mr Greg McCormack, Midway Ptd Ltd

- Dr Hans Drielsma, Forestry Tasmania

- Mr Ian Telfer, WA Plantation Resources (WAPRES)

- Mr Jim Snelson, Carter Holt Harvey (CHH)

- Mr John McNamara, Hyne & Son

- Dr Jon Ryder, Australian Paper

- Mr Terry Edwards, Forest Industries Association of Tasmania (FIAT)

- Mr Vince Erasmus, Elders Forestry

A more apt logo for the Logging Industry A more apt logo for the Logging Industry

The motives for World Forestry Day are nothing but blatant pro-logging propaganda.

Stihl Chainsawing Old-Growth Stihl Chainsawing Old-Growth

…’are you looking for the best chainsaw for cutting trees?’ ~ quote from Stihl’s website.

.

The term ‘Existence value’ deserves to be further explored and promulgated, so we can develop a greater non-utilitarian value of our natural and now rare forests. Our precious forest exists for their own sake, the forest ecosystems they support and of which we have so little comprehension of their global existence value and scarcity.

– end of article –

Tags: AFPA, Australian Forest Products Association, DSE, eco-logging, forestry, General Assembly of the European Confederation of Agriculture, greenwashing, logging industry, NAFI, National Association of Forestry Industries, Stihl, stihl chainsawing old-growth, Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment, World Forestry Day, world logging day

Posted in Threats from Deforestation, Threats from Greenwashing, Threats from Road Making | No Comments »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

August 6th, 2011

On August 6th, 2011 Tigerquoll on CanDoBetter.net stated:

to know one’s fate to know one’s fate

.

Globalisation is evangelised as the modern religion of humanism. But dare criticise it and so invoke the blind wrath of SBS devotees, and be cast out, branded a facist racist and persecuted as if a 1692 Salem witch – burned at the stake!

.