Australian native forests – are they valuable ecosystems and habitats for wildlife; or bushfire fuel hazards to be burned, before they burn?

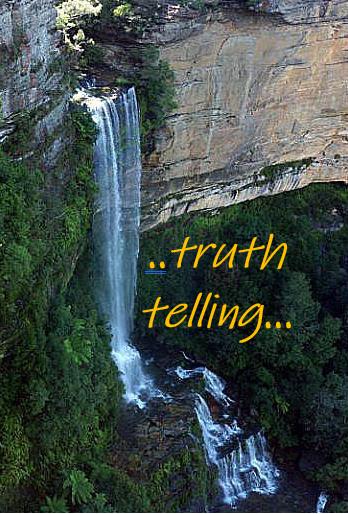

Blue Mountains wet schlerophyl forest

© Photo by Henry Gold, wilderness photographer

.

Blue Mountains wet schlerophyl forest

© Photo by Henry Gold, wilderness photographer

.

.

Bushfire Management’s root problems

.

- Bushfire Management which recognises wildlife habitat as an asset worth protecting makes the fire fighting task immensely complex. So moreover the more simplistic and cost saving rationale of ‘protecting life and property’ holds sway, where no thought is given to the conservation values or to the habitat needs of wildlife. The inculcated and unquestioned bushfire management attitude that native forests are the cause of bushfires, rather than being victims of bushfires, belies one of the three key root problems of why bushfire management is failing. Ignitions left to burn in inaccessible terrain time again have proved be devastating not just for nature and wildlife, but consequentially for human life and property. Wildfire does not discriminate.

- Bushfire Management across Australia is so poorly equipped to detect and suppress ignitions when they do occur, that out of frustration, fear has been inculcated to encourage all native forests be dismissed as bushfire hazards and ‘prescribed burned’ as a precaution. Across the New South Wales Rural Fure Service, the term is quite unequivocal – ‘Hazard Reduction‘ . Broadscale hazard reduction, euphemistically labelled ‘strategic burns‘ or deceptively ‘ecological burns‘ and has become the greatest wildlife threatening process across Australia driving wildlife extinctions.’

- Both the localised and regional impacts of bushfire and hazard reduction upon wildlife ecology are not fully understood by the relevant sciences – ecology, biology and zoology. Fire ecology is still an emerging field. The Precautionary Principle is well acknowledged across these earth sciences, yet continues to be dismissed by bushfire management. They know not what they do, but I do not forgive them.

.

Australia’s record of wildlife extinctions are the worst of any country in the past two hundred years.

‘Of the forty mammal species known to have vanished in the world in the last 200 years, almost half have been Australian. Our continent has the worst record of mammal extinctions, with over 65 mammal species having vanished in the last 50 000 years.’ [Chris Johnson, James Cook University, 2006]

.

‘Australia leads the world in mammal extinctions. Over the last two hundred years 22 mammal species have become extinct, and over 100 are now on the threatened and endangered species list, compiled as part of the federal government’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.’ [Professor Iain Gordon, research scientist in CSIRO’s new Biodiversity Theme, 2009.]

.

Uncontrolled bushfires, broadscale and frequent hazard reduction, and land clearing are the key drivers causing Australia’s remaining wildlife to disappear. Once habitat is destroyed, the landscape becomes favourable to feral predators which kill the remaining unprotected fauna. Thousands of hectares of Australia’s native forests are being burnt every year and are becoming sterile park lands devoid of undergrowth habitat. Wave after wave of habitat threats continue to undermine the layers of resilience of native fauna, until fauna simply have no defences left and populations become reduced to one local extinction after another.

James Woodford in his article ‘The dangers of fighting fire with fire‘ in the Sydney Morning Herald, 8th September 2008, incitefully observed:

‘Fighting fires with fear is a depressing annual event and easy sport on slow news days. Usually the debate fails to ask two crucial questions: does hazard reduction really do anything to save homes, and what’s the cost to native plants and animals caught in burn offs? What we do know is a lot of precious wild places are set on fire, in large part to keep happy those householders whose kitchen windows look out on gum trees.

Hazard reduction burning is flying scientifically blind. Much hazard reduction is performed to create a false sense of security rather than to reduce fire risks, and the effect on wildlife is virtually unknown. An annual bum conducted each year on Montague Island, near Narooma on the NSW far South Coast has become a ritual in which countless animals,including nesting penguins, are roasted.

The sooner we acknowledge this the sooner we can get on with the job of working out whether there is anything we can do to manage fires better. We need to know whether hazard reduction can be done without sending our wildlife down a path of firestick extinctions.’

.

.

‘Koalas may be extinct in seven years’

[Source: Sydney Morning Herald, 20070411]

.

‘Extreme drought, ferocious bushfires and urban development could make koalas extinct within seven years, environmentalists are warning. Alarms about the demise of the iconic and peculiar animal, which sleeps about 20 hours a day and eats only the leaves of the eucalyptus tree, have been raised before.

But Deborah Tabart, chief executive officer of the Australia Koala Foundation, believes the animal’s plight is as bad as she has seen it in her 20 years as a koala advocate.

“In South-East Queensland we had them listed as a vulnerable species which could go to extinction within 10 years. That could now be seven years,” she said. “The koala’s future is obviously bleak.”

South-East Queensland has the strongest koala populations in the vast country, meaning extinction in this area spells disaster for the future of the species, said Tabart.

The biggest threat is the loss of habitat due to road building and development on Australia’s east coast – traditional koala country. The joke, said Tabart, is that koalas enjoy good real estate and are often pushed out of their habitat by farming or development.

“I’ve driven pretty much the whole country and I just see environmental vandalism and destruction everywhere I go,” she said. “It’s a very sorry tale. There are [koala] management problems all over the country.”

Massive bushfires which raged in the country’s south for weeks during the summer, burning a million hectares of land, would also have killed thousands of koalas.’

[Read More]

.

.

‘A Bushfire action plan which protects people, property and nature’

[Source: The wilderness Society, 20090219, http://www.wilderness.org.au/campaigns/forests/bushfire-action-plan]

.

In the immediate aftermath of the devastating Victorian Bushfires of 2009, The Wilderness Society, in response to bushfire management’s quick blaming of the native forests for the bushfires; drafted a ‘Bushfire Action Plan‘ that sought to recognise the need to protect nature along with people and their property.

In the immediate aftermath of the devastating Victorian Bushfires of 2009, The Wilderness Society, in response to bushfire management’s quick blaming of the native forests for the bushfires; drafted a ‘Bushfire Action Plan‘ that sought to recognise the need to protect nature along with people and their property.

.

‘Bushfire remains one of the most complex and difficult aspects of our environment to deal with. Climate change is expected to make things even tougher, with increases in the number of high fire danger days and the number of people and houses at risk increasing with the tree/sea change phenomenon.

With the onset of climate change, mega-bushfires that burn massive areas are expected to occur more often.

A joint CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology study of the impact of climate change in bushfires found parts of Victoria faced up to 65% more days of extreme fire risk by 2020, and 230% more by mid-century.

Yet clearly we have a lot to learn and the Royal Commission will set a new agenda for land and fire management, prevention and response. Many challenges will remain but some aspects seem clear. We need more money and support for fire fighters if we are to successfully protect life, property and the environment. Two key areas are the early detection of fires including the use of aerial surveillance and remote sensing especially in remote areas, increasing rapid response capacity including more “Elvis” helicopters to fight bushfires as soon as they start.

The outstanding work of firefighters on the front line needs to be backed up with the best available knowledge, planning and resources to ensure operations are as effective as possible in protecting people, property and nature. There is an urgent need to increase investment in these areas and rapidly establish scientific underpinning to fire management, as well as properly resourcing implementation and fire operations.

We also need more information for government and community about how to deliver fire management in a way that also protects the natural environment and our unique wildlife.

Fuel reduction burning has an important place in the fire management toolbox, and we support its place in scientifically underpinned fire management for the protection of life, property and the environment.

The issue of fuel reduction burning often dominates the fire debate, as if it is the only fire management tool. But it’s important to remember that this is only one tool in fire management, and not the silver bullet that will fire proof the landscape.

Environmental groups want to see the science that supports the current fuel reduction program, including a scientific justification for so-called hazard reduction burns in specific areas and the scientific justification for the route and extent of fire break establishment. Environmental groups are particularly concerned about the lack of impact assessment of these programs on biodiversity, particularly given their uncertain benefits to reduce the extent, frequency and severity of fire.

Views on these measures tend towards two extremes. One extreme is that we should fuel reduction burn all forest areas every 20 years and carve out thousands of kilometres of fire breaks, the other is that all our forests are wilderness areas which should just be allowed to burn and not manage our forests for fire at all.

For the Australian bush to be healthy and to protect people, property and nature we need a scientifically based balance between these extremes.

Fire management is not ‘one size fits all’ when it comes to the Australian bush. It needs to be targeted and specific, because we know that different kinds of bush respond differently to fire and therefore need different management. For native plants and animals to survive, fire management needs to promote “good” fire at the right time of year, of the right type and size. And that varies with vegetation type and resident native animals. Grasslands will require more frequent fires compared with forests, while areas such as rainforest will need to be protected from fire altogether.

That’s why we need good ecological science informing fire management, which has come a long way in understanding what’s best for native plants, but we need a better understanding of what fire management is best for protecting wildlife and avoiding extinctions. Its critical that scientists, fire agencies and governments work together to understand how to best manage fire to protect habitat for endangered wildlife, because no one wants fire management to lead to extinctions.

Of course, the protection of life & property needs to come first in fire management – but we can do that while also protecting nature and wildlife. A balanced approach is to prioritise the protection of life and property in areas close to farms and townships, and to prioritise fire management for the environment in remote areas and national parks.

A continuation of the expansion in knowledge, resources and support for fire management and community preparedness will best ensure the protection of life, property and the environment into the future…

.

We have developed a 6-point plan to reduce the bushfire risk and help protect people, property, wildlife and their habitat.

- Improve aerial surveillance to detect bushfires as soon as they start.

- Ramp up hi-tech, quick response capability, including more ‘Elvis’ helicopters to fight bushfires as soon as they ignite.

- More research into fire behaviour and the impact of fire on wildlife and their habitat.

- Around towns and urban areas – prioritise the protection of life and property with fuel reduction and fire break management plans.

- In remote areas and National Parks – prioritise the protection of wildlife and their habitat through scientifically-based fire management plans.

- Make native forests resistant to mega-fires by protecting old-growth forests, rainforests and water catchments from woodchipping and moving logging into existing plantations.

.

.

Critique of Roger Underwood’s Criticism of TWS ‘6-Point Plan‘

.

On 12th February 2009, Roger Underwood, a former rural firefighter and a forestry industry employee in Western Australia, had his article published in The Australian newspaper criticising the above recommendations of The Wilderness Society (TWS).

On 12th February 2009, Roger Underwood, a former rural firefighter and a forestry industry employee in Western Australia, had his article published in The Australian newspaper criticising the above recommendations of The Wilderness Society (TWS).

Regrettably, rather than offering constructive criticism and proposing counter arguments with supportive evidence, Underwood instead dismisses the Wilderness Society’s contribution, but disappointingly with empty rhetoric. Underwood states upfront:

“the trouble with the society’s action plan to reduce the risk of bushfires is that it won’t work.“

.

The Wilderness Society’s six-point action plan aims to counter the current bushfire management strategy that relies upon hazard reduction burning and the ecological damage this is causing – ‘destroying nature’, ‘pushing wildlife closer to extinction’, ‘increasing the fire risk to people and properties by making areas more fire prone’.

Underwood claims that statistics exist showing no massive increase in prescribed burning, but in fact that prescribed burning has declined. Yet Underwood fails to provide nor even reference any such statistics. He fails to recognise that both bushfires and prescribed burning collectively cause adverse impacts on wildlife. If all burning of native vegetation, however caused, is included in the assessment, then would statistics indeed show an increasing trend in the natural area affected by fire in Australia?

.

‘Burn it before it burns’ Theory

.

Underwood questions the wildlife extinction problem without any basis. He then adopts the ”old chestnut‘ theory of blaming the threat to wildlife on ‘killer bushfires‘. ‘Killer bushfires’ (the firestorm threat) has become the default justification by bushfire management for its policy of prescribed burning. This is the ‘Burn it before it burns!‘ defeatist attitude. If one burns the bush, there will be no bush to burn. Underwood’s claim that ‘killer bushfires’ are a “consequence of insufficient prescribed burning” is a self-serving slippery slope fallacy. If nature is an asset of value to be protected, then it is defeatist to damage it to prevent it from damage. The history of so-called ‘controlled burns‘ have an infamous reputation of getting out of control and becoming wildfires. If the attitude of burning as much of the bush as possible to avoid uncontrolled wildfire, then then paradoxically the implied incentive is to let controlled burns burn as much as possible to minimise the risk of unexpected fires in the same area.

.

In respect to each of The Wilderness Society’s (TWS) Six Point Plan, one counters Underwood’s responses as follows:

.

1: Improve aerial surveillance to detect bushfires as soon as they start

.

Underwood supports aerial detection as “a first-rate resource and a comprehensive system” but says that it can fail completely under hot, unstable atmospheric conditions and when there are very high winds. However, fire towers and aircraft are not the means of bushfire surveillance today. Low orbiting geostationary satellites with infrared and high resolution cameras can now spot individual cars in real time and through cloud and smoke. Satellites are not affected by atmospheric conditions such as high winds or hot temperatures. Modis-Fire is one company that specialises in such satellite technologies.

In addition, the CSIRO, with the Department of Defence and Geoscience Australia, has developed an internet-based satellite mapping system called ‘Sentinel Hotspots‘. Sentinel Hotspots gives emergency service managers access to the latest fire location information using satellite data. Fire fighting organisations across Australia have used this new strategic management tool, since it was launched in 2002, to identify and zoom in on fire hotspots. [Read More]

In 2003, an article in the International Journal of Wildland Fire entitled ‘Feasibility of forest-fire smoke detection using lidar‘ extolled the virtues of forest fire detection by smoke sensing with single-wavelength lidar.

Such technologies are available if the political will was met with appropriate investment. Such technologies could be available to a military-controlled national body, but unlikely to be available to volunteer members of the public. It all depends on the standard of performance Australians expect from bushfire management.

.

2: Ramp up hi-tech, quick response capability, including more ‘Elvis’ helicopters to fight bushfires as soon as they ignite.

.

Underwood dismisses aerial fire-bombing as a “dream” that “has never succeeded in Australia, and not even in the US” and “next to useless“.

Well, it seems Underwood is contradicted by the recent decisions of Australia State Governments across Australia’s eastern seaboard to charter not just one Erikson Aircrane but three. Not only was Elvis contracted from the United States in Summer 2010 to Victoria, “Elvis” was based in Essendon, ‘Marty‘ was based in Gippsland and ‘Elsie‘ was based in Ballarat. Clearly, the Victorian State Government considers the cost of these three aircraft justifiably cost-effective in offering quick response capability to fight bushfires.

Dedicated Fire Fighting Erikson Aircrane ‘Elsie‘ based in Ballarat, Victoria during the 2010 Summer

© Photo ABC Ballarat http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2010/12/22/3099609.htm

.

In South Australia, the Country Fire Service (CFS) believes in the philosophy of hitting a fire ‘hard and fast’.

.

‘CFS volunteers and aerial firefighting aircraft are responded within minutes of a bushfire being reported and as many resources as possible are deployed to keep the fire small and reduce the chance of it getting out of control. It is not widely known that South Australia has a world class initial attack strategy of aerial firefighting. The value of a rapid aerial firefighting approach has been supported by Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre research. In their 2009 report titled ‘The cost-effectiveness of aerial fire fighting in Australia, the Research Centre wrote the following in their summary

.

The results of the analysis show that the use of ground resources with initial aerial support is the most economically efficient approach to fire suppression. Aircraft are economically efficient where they are able to reach and knock down a fire well before the ground crew arrives. This buys time for the ground forces to arrive and complete the containment. Rapid deployment of aerial suppression resources is important. This advantage is much greater in remote or otherwise inaccessible terrain. Where other suppression resources are unable to reach the fire event within a reasonable time period, sole use of aircraft is economically justified.’

[http://www.bushfirecrc.com.au/research/downloads/The-Cost-Effectiveness-of-Aerial-Fire-Fighting-in-Australia.pdf].

.

Dedicated Fire Fighting Erikson Aircrane ‘Elsie‘ based in Ballarat, Victoria during the 2010 Summer

© Photo ABC Ballarat http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2010/12/22/3099609.htm

.

In South Australia, the Country Fire Service (CFS) believes in the philosophy of hitting a fire ‘hard and fast’.

.

‘CFS volunteers and aerial firefighting aircraft are responded within minutes of a bushfire being reported and as many resources as possible are deployed to keep the fire small and reduce the chance of it getting out of control. It is not widely known that South Australia has a world class initial attack strategy of aerial firefighting. The value of a rapid aerial firefighting approach has been supported by Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre research. In their 2009 report titled ‘The cost-effectiveness of aerial fire fighting in Australia, the Research Centre wrote the following in their summary

.

The results of the analysis show that the use of ground resources with initial aerial support is the most economically efficient approach to fire suppression. Aircraft are economically efficient where they are able to reach and knock down a fire well before the ground crew arrives. This buys time for the ground forces to arrive and complete the containment. Rapid deployment of aerial suppression resources is important. This advantage is much greater in remote or otherwise inaccessible terrain. Where other suppression resources are unable to reach the fire event within a reasonable time period, sole use of aircraft is economically justified.’

[http://www.bushfirecrc.com.au/research/downloads/The-Cost-Effectiveness-of-Aerial-Fire-Fighting-in-Australia.pdf].

.

Underwood claims that: “Elvis-type aircranes cost a fortune, burn massive amounts of fossil fuel, use gigalitres of precious water and are ineffective in stopping the run of a crown fire that is throwing spot fires. Water bombers do good work protecting houses from small grass fires. But against a big, hot forest fire and during night-time they are next to useless.”

Underwood conveys a sense of dogged reliance in traditional fire truck centric thinking as if to preserve an old firie culture of ‘we know best‘ and ‘nothing is going to change our thinking‘ mindset. May be it is out of petty envy wherein many volunteer firies can command trucks but wouldn’t have a clue flying helicopters and so would feel sidelined.

Well, since the 2009 Victorian Bushfires, more than A$50 million worth of new initiatives have been introduced or are under development.

“Further changes are likely to be introduced as the Royal Commission, which was established to investigate the Black Saturday disaster, is ongoing. Aerial firefighting is set to be addressed by the commission. Among new initiatives in Victoria is a A$10 million trial of a very large air tanker (VLAT) – the first-ever such experiment in the country. On 14 December, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 Super Tanker, leased from US company 10 Tanker Air Carrier, arrived in Melbourne. Australian regulator, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority, and underwent final compliance assessment to allow it to enter service in January.”

.

[Source : http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2010/02/09/338056/australia-puts-firefighting-tankers-to-the-test.html]

Underwood may well dismiss aerial suppression technology as ‘razzle-dazzle‘, but he is right to state that such investment requires governments to put more resources into research and into monitoring bushfire outcomes, including the environmental impacts of large, high-intensity bushfires and continuous feedback to management systems from real-world experience out in the forest.’

.

3: More research into fire behaviour and the impact of fire on wildlife and their habitat

.

While Underwood claims that he supports more research into fire behaviour and fire impacts, he is dismissive of the conclusions of much of the research already done, but offers no explanation. This seems an internal contradiction. What are the conclusions of the research?

Underwood claims the conclusions do not support the Wilderness Society’s agenda. How so? What is TWS agenda?

Underwood conveys an unsubstantiated bias against the Wilderness Society, only offering an ad hominem fallacious argument – attacking the messenger, not the argument.

.

The science on fire ecology is still emerging. The Wilderness Society validly states above that ‘bushfire remains one of the most complex and difficult aspects of our environment to deal with‘, that ‘there is an urgent need to increase investment in these areas and rapidly establish scientific underpinning to fire management, as well as properly resourcing implementation and fire operations‘ and ‘the lack of impact assessment of these programs on biodiversity, particularly given their uncertain benefits to reduce the extent, frequency and severity of fire‘.

.

4: Around towns and urban areas – prioritise the protection of life and property with fuel reduction and fire break management plans.

.

Underwood here perceives an inconsistency in TWS Action Plan – suggesting its support for fuel reduction around urban areas contradicts its claim that fuel reduction makes the burned areas “more fire prone”. However, this action item is about prioritising fuel reduction on a localised basis around the immediate areas where life and property are located.

Whereas broadscale hazard reduction that is carried out many miles from human settlements has become a new strategy of bushfire management. The excuse used is euphemistically termed a ‘strategic burn‘ or even an ‘ecological burn‘ in the name of encouraging biodiversity. Except that the practice seems to be a leftover habit from the Vietnam War in which helicopters are used to drop incendiaries indiscriminately into remote areas without any care for the consequences.

A so-called ‘ecological burn‘ of Mt Cloudmaker

This was conducted by helicopter incendiary by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (DECCW)

in the remote Krungle Bungle Range of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area

(Photo by editor from Hargraves Lookout, Shipley Plateau, 20080405 , free in public domain)

A so-called ‘ecological burn‘ of Mt Cloudmaker

This was conducted by helicopter incendiary by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (DECCW)

in the remote Krungle Bungle Range of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area

(Photo by editor from Hargraves Lookout, Shipley Plateau, 20080405 , free in public domain)

.

A recent example is the ‘strategic burn’ authorised and executed by the NSW Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water (DECCW) in the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area on 12th May 2010. Some 2500 hectares of remote wilderness was deliberately set alight around Massif Ridge, some 12 kilometres south of the town of Woodford in wild inaccessible forested area of the World Heritage Area. The excuse was to reduce the available ‘fuel’ (native vegetation) for potential future wildfires. [>Read More: ‘National Parks burning biodiversity‘ ]

.

5: In remote areas and National Parks – prioritise the protection of wildlife and their habitat through scientifically-based fire management plans.

.

Underwood contends another stock standard industry claim that where native forests have been protected, they have naturally accumulated fuel loads in which sooner or later an uncontrollable landscape-level fire occurs. So his anthropocentric theory runs that is humanity’s responsibility not to let nature be nature, but to control nature and so to burn the bush before it burns. This theory is premised on the defeatist approach that in the event of a bushfire, bushfire management is not in a position to detect and suppress it.

And so Underwood, poses the standard industry response of “more frequent planned burning under mild conditions“. He assumes that leaving the overstorey and the soil intact will ensures a diversity of habitat for wildlife. Yet Underwood is not a zoologist and has no understanding of the vital role that dense ground vegetation provides to Australia’s native ground dwelling mammals (e.g.the Long-footed Potoroo, Spotted-tailed quoll, Eastern Pygmy Possum, the Petrogale penicillata, Broad-toothed Rat, Bolam’s Mouse, the Smoky Mouse, the Eastern Chestnut Mouse, the Long-nosed Bandicoot), as well as nexting birds, flightless birds, amphibians and reptiles.

Eastern Quoll – Dasyurus viverrinus – EXTINCT on mainland Australia

© Photo by Andrea Little http://www.mtrothwell.com.au/gallery.html

Eastern Quoll – Dasyurus viverrinus – EXTINCT on mainland Australia

© Photo by Andrea Little http://www.mtrothwell.com.au/gallery.html

.

Underwood’s view reflects the simplistic misguided view of biodiversity of most of Australia’s bushfire management – that the presence of trees and regrowth of fire-tolerant plants equates to biodiversity.

Can Underwood name one species of Australian fauna that is fire tolerant?

Underwood misinterprets the text of TWS which advocates an holistic fire management system, not as a silver bullet or ‘one-size-fits- all’ convenient panacea that pretends to fire proof the landscape. The only guarantee of ‘one-size-fits- all’ hazard recution is a sterile forest devoid of biodiversity and causing local species extinctions. TWS argues for a scientifically-based and balance approach recognising that some forest ecosystems like rainforests are most definitively fire-intolerant.

.

6: Make native forests resistant to mega-fires by protecting old-growth forests, rainforests and water catchments from woodchipping and moving logging into existing plantations

Underwood challenges this last item stating there is no evidence that old growth forest is less likely to burn than the regrowth forests. This is false. Australian native forests that regrow after fire are those that are fire-resistant. Typically, these genus (Eucalypt and Acacia) regrow quickly and become dense mono-cultures. If a fire passes through again, the fire is often more intense and devastating. Old growth forests, rainforests and riparian vegetation around water catchments tend to be moist and so less prone to bushfires.

But this sixth item is not about the relative propensity of old growth forests to burn more readily than regrowth forests, so Underwood’s argument is a distracting red herring. TWS’ aim here is more about placing a higher value on old growth and rainforests due to their greater biodiversity and due to their increasing scarcity. Clearly, TWS is ideologically opposed to woodchipping and logging of old growth forests and rainforests. Logging operations typically involve follow up deliberate burning and such fires have frequently got out of control. Underwood’s needling criticism of TWS for having a lack of knowledge of fire physics or bushfire experience is a typical defensive criticism leveled at anyone who dares to challenge bushfire management. Conversely, if Underwood has the prerequisite knowledge of fire physics or bushfire experience, he is not very forthcoming except to defend the status quo of bushfire management.

The recent bushfire results are demonstrating that bushfire management is increasingly unable to cope with bushfire catastrophes nor meet the expectations of the public to protect life, property and nature.

.

.

Further Reading:

.

[1] ‘Studies of the ground-dwelling mammals of eucalypt forests in south-eastern New South Wales: the species, their abundance and distribution‘ by PC Catling and RJ Burt, CSIRO, 1994, http://www.publish.csiro.au/paper/WR9940219.htm

.

[2] ‘Australia’s Mammal Extinctions – A 50,000-Year History‘, by Chris Johnson, 2006, James Cook University, North Queensland. http://www.cambridge.org/aus/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521686600

.

[3] ‘Solving Australia’s mammal extinction crisis‘, (2009) by Professor Iain Gordon, research scientist in CSIRO’s new Biodiversity Theme, ABC Science programme. He chaired a symposium on Australia’s mammal extinction crisis at the 10th International Congress of Ecology in Brisbane August 2009. http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2009/09/02/2674674.htm

.

[4] ‘Koalas may be extinct in seven years‘ , Sydney Morning Herald, 20070411, http://www.smh.com.au/news/environment/koalas-may-be-extinct-in-seven-years/2007/04/11/1175971155875.html

.

[5] ‘A Bushfire action plan which protects people, property and nature‘, The Wilderness Society, 20090219, http://www.wilderness.org.au/campaigns/forests/bushfire-action-plan

.

[6] ‘Manage bush better so climate won’t matter‘, by Roger Underwood (ex-firefighter), The Australian newspaper, 20090212, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/manage-bush-better-so-climate-wont-matter/story-e6frg73o-1111118824093

.

[7] ‘Locating bushfires as they happen‘, CSIRO – Sentinel Hotspots, http://www.csiro.au/solutions/Sentinel.html

.

[8] ‘Modis-Fire’ satellite bushfire detection, http://modis-fire.umd.edu/Active_Fire_Products.html

.

[9] ‘Elsie’s first day on the job, Ballarat’s fire fighting helicopter‘, by Prue Bentley (ABC TV Ballarat), 20101222, http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2010/12/22/3099609.htm

.

[10] ‘South Australia – Country Fire Service – Factors that influence aircraft selection‘ – http://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/about_us/aerial_firefighting/aircraft_selection.jsp

.

[11] ‘Australia puts firefighting tankers to the test‘, Fight Global 20090209, http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2010/02/09/338056/australia-puts-firefighting-tankers-to-the-test.html

.

[12] ‘Bushfire-CRC – Aviation content’, http://www.bushfirecrc.com/category/bushfiretopic/aviation.

.

[13] ‘Towards New Information Tools for Understanding Bushfire Risk at the Urban Interface‘, 2004, R. Blanchi, J. Leonard, D. Maughan, Bushfire-CRC, CSIRO Manufacturing & Infrastructure Technology, Bushfire Research. [Read full report]

[end of article]

.

Golden Bandicoot is under threat of extinction in The Kimberley.

Golden Bandicoot is under threat of extinction in The Kimberley.

Wyulda, or Scaly-tailed Possum (Wyulda squamicaudata)

endemic to the Kimberley, and highly sensitive to bushfires

Wyulda, or Scaly-tailed Possum (Wyulda squamicaudata)

endemic to the Kimberley, and highly sensitive to bushfires

Northern Quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus)

Native to the Kimberley, but seriously at risk from feral cats and bushfires

Northern Quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus)

Native to the Kimberley, but seriously at risk from feral cats and bushfires Floodplain wetland of the Hann River

as it leaves the Phillips Range,Marion Downs Wildlife Sanctuary, The Kimberley.

© Photo by Wayne Lawler, Australian Wildlife Conservancy

Floodplain wetland of the Hann River

as it leaves the Phillips Range,Marion Downs Wildlife Sanctuary, The Kimberley.

© Photo by Wayne Lawler, Australian Wildlife Conservancy

Cat killing wildlife

[Source: Australian Wildlife Carers Network, ^http://www.ozarkwild.org/cats.php,

Photo: Australian Government]

Cat killing wildlife

[Source: Australian Wildlife Carers Network, ^http://www.ozarkwild.org/cats.php,

Photo: Australian Government]