Blue Mountains Swamps: save or bulldoze?

Tuesday, October 16th, 2012 Tasman Flax-lily (Dianella tasmanica) (blue berry) in a Blue Mountains Swamp

At the headwaters of Katoomba Creek, Katoomba

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

Tasman Flax-lily (Dianella tasmanica) (blue berry) in a Blue Mountains Swamp

At the headwaters of Katoomba Creek, Katoomba

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

.

Q: When is a protected swamp not deemed a swamp and so not worthy of protection?

Closed sedgeland dominated by Soft Twig Rush (Baumea rubiginosa)

across a Blue Mountains Swamp along the headwaters of Yosemite Creek, Katoomba

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

Closed sedgeland dominated by Soft Twig Rush (Baumea rubiginosa)

across a Blue Mountains Swamp along the headwaters of Yosemite Creek, Katoomba

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

.

A: When unqualified local Council development planning staff are selectively blind to allow for housing development.

Colorbond fence encroaching into the above Blue Mountains Swamp

Along the headwaters of Yosemite Creek, Katoomba

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

Colorbond fence encroaching into the above Blue Mountains Swamp

Along the headwaters of Yosemite Creek, Katoomba

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

.

Q: When is a protected swamp deemed a swamp worthy of protection?

A: When quasi-qualified local Council environmental staff are selectively seeking public relations kudos and grant funding.

The Save Our Swamps (SOS) Project

The Save Our Swamps (SOS) Project

.

The Save Our Swamps (SOS) Project is a recent joint project between Blue Mountains City Council, Gosford City Council, Lithgow City Council and Wingecarribee Shire Council to protect and restore the federally listed Temperate Highland Peat Swamps on Sandstone endangered ecological community.

It is funded through a 12 month $400,000 federal Caring for Country grant operating across all four LGAs as well as a 3 year $250,000 NSW Environmental Trust grant focused on the Blue Mountains City Council and Lithgow City Council Local Government Areas. [Source: Blue Mountains Council, ^http://saveourswamps.com.au/index.php]

.

Blue Mountains Swamp

A ‘hanging swamp‘ – hanging on a steep slope

Blue Mountains Swamp

A ‘hanging swamp‘ – hanging on a steep slope.

The Blue Mountains National Park is one of seven national parks which collectively comprise a million hectares of the Greater Blue Mountains Area, which since 2000 has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This area is protected internationally for (1) its outstanding examples representing significant on-going ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems and communities of plants and animals and (2) contain the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation. [Read More about ^The Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage values]

.

Since 12th May 2005, ‘Temperate Highland Peat Swamps on Sandstone‘ have been recognised as an important and rare ecological community listed as Endangered under the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, as well as within New South Wales under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (NSW) (TSC Act).

So naturally, one would expect such swamps to be identified, mapped and ecologically protected – one would expect. .

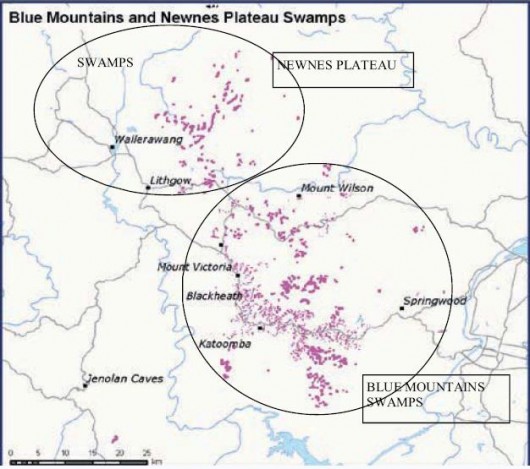

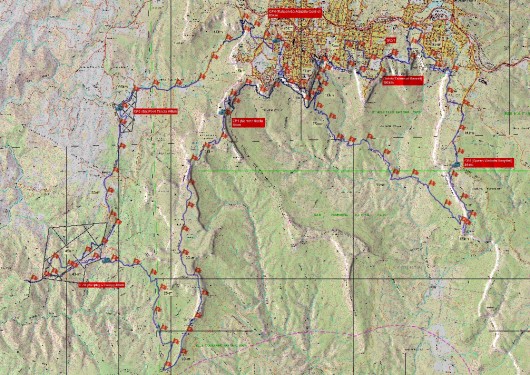

These swamps occur naturally in very few places on the planet, as shown (in red) in the following distribution map within south eastern Australia:

. Temperate Highland Peat Swamps on Sandstone – Global Distribution Map

[Source: Australian Government, Department of Environment et al.,

Temperate Highland Peat Swamps on Sandstone – Global Distribution Map

[Source: Australian Government, Department of Environment et al.,^http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicshowcommunity.pl?id=32#Distribution, accessed 20121015]

.

Blue Mountains Swamps are included as part of the Temperate Highland Peat Swamps on Sandstone. These are the top two red areas in the above map.

The Blue Mountains west of Sydney are Triassic sandstone plateaux. Blue Mountain Swamps occur in shallow, low-sloping, often narrow headwater valleys (Keith and Benson 1988; Benson and Keith 1990), on long gentle open drainage lines in the lowest foot slopes, low-lying broad valley floors and alluvial flats (Department of Environment and Conservation 2006), and in gully heads, open depressions on ridgetops and steep valley sides associated with semi-permanent water seepage (Holland et al. 1992; Blue Mountains City Council 2005; Department of Environment and Conservation 2006).

Farmers Creek Swamp

Newnes Plateau, Blue Mountains – is it protected? Or just not targeted for development yet?

Grevillea acanthifolia (pink flower) in the foreground

[Source: Lithgow Environment Group, ^http://www.lithgowenvironment.org/swamp_watch2.shtml]

Farmers Creek Swamp

Newnes Plateau, Blue Mountains – is it protected? Or just not targeted for development yet?

Grevillea acanthifolia (pink flower) in the foreground

[Source: Lithgow Environment Group, ^http://www.lithgowenvironment.org/swamp_watch2.shtml]

.

Most of these swamps are situated within the Greater Blue Mountains Area and so are ecologically protected, but many are not. Many Blue Mountains Swamps are situated just outside on the fringe lands. Those fringe lands lie on the bush interface with human residential settlement and despite their environmental protection on paper are at risk of being bulldozed for housing development. Such threats from development are referred to as ‘edge effects‘. These swamps are on the edge of housing development, or put the more chronological way, housing development is being allowed to encroach upon the edge of these swamps that were there first. Other Blue Mountains Swamps such as those up on Newnes Plateau are at risk of being bulldozed and drained for mining.

According to the Blue Mountains Council, there are less than 3,000 hectares of Blue Mountains Swamp in existence. As they predominantly comprise many small areas, they are very susceptible to edge effects. As the urban footprint expands to the edges of the plateau, the swamps are coming under ever increasing pressure.

.

- Clearing for urban development

- Urban runoff – sediment deposition, tunnelling and channelisation from stormwater discharges

- Bushfire (both ‘wild’ and ‘hazard’ reduction)

- Weed invasion

- Nutrient enrichment (urban runoff)

- Mowing

- Grazing

- Water extraction (bores, tapping natural springs and building dams)

.

[Source: ‘Blue Mountains Swamps’, Blue Mountains Council, ^http://www.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/sustainableliving/environmentalinformation/livingcatchments/bluemountainsswamps/].

Blue Mountains Swamp

Here an acre of pristine Coral Fern (Gleichenia dicarpa) burned at Devil’s Hole, Katoomba

It was set fire to (‘hazard reduced’) by National Parks and Wildlife (NSW) on 20120911

Photo by Editor 20120922, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

Blue Mountains Swamp

Here an acre of pristine Coral Fern (Gleichenia dicarpa) burned at Devil’s Hole, Katoomba

It was set fire to (‘hazard reduced’) by National Parks and Wildlife (NSW) on 20120911

Photo by Editor 20120922, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

..

Blue Mountains Swamps – substrate characteristics

.

Blue Mountains Swamps are characterised by the constant presence of groundwater seeping along the top of impermeable claystone layers in the sandstone and reaches the surface where the claystone protrudes (Keith and Benson 1988; Holland et al. 1992; Blue Mountains City Council 2005).

The substrate tends to be a shallow black to grey coloured acid, peaty, loamy sandy soil with organic matter and are poorly drained and so tend to be either constantly or intermittently water logged (Hope and Southern 1983; Keith and Benson 1988; Benson and Keith 1990; Stricker and Brown 1994; Stricker and Wall 1994; Winning and Brown 1994; Stricker and Stroinovsky 1995; Benson and McDougall 1997; Whinam and Chilcott 2002; Department of Environment and Conservation 2006).

Blue Mountains Swamp on Newnes Plateau

Blue Mountains Swamp on Newnes Plateau

The swamps naturally trap sediment and disperse rain water over a wide area and protect floors of headwater valleys from erosion. They vary in structure and species composition according to geology, topographic location, depth of the water table, extent and duration of water logging and bushfire frequency.

.

Blue Mountains Swamps – vegetation variation

.

The structure of Blue Mountains Swamp vegetation varies from open shrubland to closed heath or open heath (dominated by shrub species but with a sedge and graminoid understorey and occasionally with scattered low trees) to sedgeland and closed sedgeland. The Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area ids listed for its outstanding natural values, a major component of which is the high number of eucalypt species and eucalypt-dominated communities. These can be found in a great variety of plant communities including within and upslope of Blue Mountains Swamps.

Topographic location, hydrology and soils significantly influence the dominant species composition. Structure of the vegetation varies from closed heath or scrub to open heath to closed sedgeland or fernland. The common cross-feature with all types is the presence of frequently waterlogged soil.

The Gully Swamp

Dominant tree canopy is Eucalyptus oreades

This one’s ‘protected’ as an Aboriginal Place under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW), Part 6

Yet it is infested with environmental and noxious weeds – so what does ‘protected’ mean?

(Photo by Editor 20110502, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge)

The Gully Swamp

Dominant tree canopy is Eucalyptus oreades

This one’s ‘protected’ as an Aboriginal Place under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW), Part 6

Yet it is infested with environmental and noxious weeds – so what does ‘protected’ mean?

(Photo by Editor 20110502, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge)

.

Blue Mountains Swamps – Known Tree Species

.

- Eucalyptus mannifera subsp. gullickii

- Mountain Swamp Gum (Eucalyptus aquatica)

- Eucalyptus copulans

- Ed: Blue Mountains Ash (Eucalyptus oreades), only at creek headwaters around Katoomba

Eucalyptus mannifera (subspecies ‘gullickii’)

Found naturally in a Blue Mountains Swamp

Eucalyptus mannifera (subspecies ‘gullickii’)

Found naturally in a Blue Mountains Swamp

.

Blue Mountains Swamps – Known Shrub Species

.

- Flax-leaf Heath Myrtle (Baeckea linifolia)

- Leptospermum juniperinum

- Hakea teretifolia

- Leptospermum grandifolium

- Grevillea acanthifolia (subspecies ‘acanthifolia’)

- Leptospermum polygalifolium

- Banksia spinulosa

- Almaleea incurvata

- Epacris obtusifolia

- Epacris hamiltonii

- Sprengelia incarnata

- Deane’s Boronia (Boronia deanei)

- Persoonia hindii

- Swamp Bush-pea (Pultenaea glabra)

- Bantam Bush-pea (Pultenaea parrisiae)

- Dwarf Kerrawang (Rulingia prostrata)

.

Flax-leaf Heath Myrtle (Baeckea linifolia)

In a Blue Mountains Swamp, flowering in late summer

(Photo by Editor 20080128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge)

Flax-leaf Heath Myrtle (Baeckea linifolia)

In a Blue Mountains Swamp, flowering in late summer

(Photo by Editor 20080128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge)

.

Blue Mountains Swamps – Known Fern Species

.

- Water ferns (Blechnum nudum)

- Pouched Coral ferns Gleichenia spp (G. dicarpa and G. microphylla)

- Umbrella ferns Sticherus spp

- King Fern (Todea barbara)

- Drosera binata

.

Blue Mountains Swamp – is this one protected?

Blue Mountains Swamp – is this one protected?

.

Blue Mountains Swamps – Known Sedge Species

.

- Large tussock sedge, Gymnoschoenus sphaerocephalus

- Rhizomatous sedges and cord rushes:

- Soft Twig Rush (Baumea rubiginosa)

- Lepidosperma limicola

- Ptilothrix deusta

- Lepyrodia scariosa

- Leptocarpus tenax

- Cord-rush (Baloskion longipes)

.

‘Edge Effects’ – when housing development is allowed to encroach upon Blue Mountains Swamps

(Where Fifth Avenue Katoomba has priority over the headwaters of Yosemite Creek, before it enters the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area)

Tree species here is Eucalyptus mannifera subsp. gullickii

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

‘Edge Effects’ – when housing development is allowed to encroach upon Blue Mountains Swamps

(Where Fifth Avenue Katoomba has priority over the headwaters of Yosemite Creek, before it enters the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area)

Tree species here is Eucalyptus mannifera subsp. gullickii

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

.

Blue Mountains Swamps – Known Grasses and Herbs Species

.

- Deyeuxia spp (D. gunniana, D. quadriseta),

- Swamp Millet (sachne globosa )

- Lachnogrostis filiformis

- Poa spp (P. labillardierei var. labillardierei, P. sieberiana)

- Tetrarrhena turfosa

- Entolasia stricta

- Dampiera stricta

- Mirbelia rubiifolia

- Gonocarpus teucrioides

- Carex klaphakei

- Derwentia blakelyi

- Wingecarribee Gentian ( Gentiana wingecarribiensis)

- Lepidosperma evansianum

- Yellow Loose Strife (Lysimachia vulgaris var. davurica)

- Tawny Leek-orchid (Prasophyllum fuscum)

- Dark Leek-orchid (Prasophyllum uroglossum)

- Large Tongue Orchid (Cryptostylis subulata)

.

Large Tongue Orchid (Cryptostylis subulata)

Blue Mountains Swamp

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

Large Tongue Orchid (Cryptostylis subulata)

Blue Mountains Swamp

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

.

For further Reading visit: ^Temperate Highland Peat Swamps on Sandstone , ^Blue Mountains Swamps in the Sydney Basin Bioregion – profile

.

So what differentiates a Blue Mountains Swamp?

.

What is common across the above varying substrate and vegetation characteristics, that differentiates a Blue Mountains Swamp from other vegetation communities are the following attributes:

- Situated on the Narrabeen Sandstone plateaux across the Blue Mountains region

- Underlying sandstone, ironstone and claystone bedrock forming a horizontal impermeable layer

- Ancient peaty sandy soil with organic matter that is poorly drained

- Presence of groundwater

- Constantly or intermediately waterlogged soil

- Locally native vegetation that thrives in such waterlogged soils

.

Q: But where do the spatial limits of a Blue Mountains Swamp begin and end? Are Blue Mountains Swamps dependent upon the health of adjoining vegetation communities, particularly of those upstream.

A: Probably, but who knows and who is researching Blue Mountains Swamps?

Q: Is it the physical characteristics that differentiate a Blue Mountains Swamp from other less significant vegetation communities or is it our selective attitudes that decide whether to protect it or condemn it?

God Government Death Lever

God Government Death Lever

.

A Save or Bulldoze Case Study:

‘Katoomba Creek Swamp at Twynam Street’

.

Katoomba Creek Swamp

With a cluster of magnificent King Ferns (Todea barbara) up the back, which are dependent upon constant ground water seepage

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

Katoomba Creek Swamp

With a cluster of magnificent King Ferns (Todea barbara) up the back, which are dependent upon constant ground water seepage

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

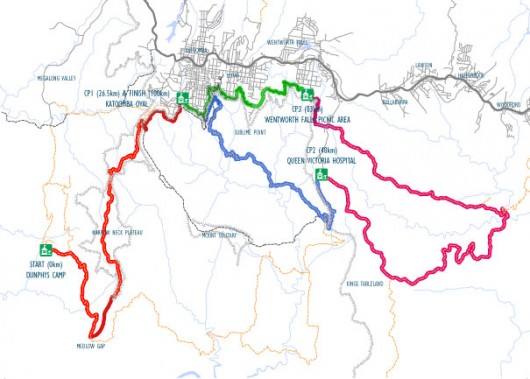

Katoomba Creek in the Upper Central Blue Mountains flows northward from a central plateau into the Grose Valley within the Blue Mountains National Park.

Katoomba Creek Swamp

Dominated by Pouched Coral Ferns (Gleichenia dicarpa), which are dependent upon constant ground water seepage

Tree canopy is Blue Mountains Ash (Eucalyptus oreades), which is rare and in the Blue Mountains found only around Katoomba

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

Katoomba Creek Swamp

Dominated by Pouched Coral Ferns (Gleichenia dicarpa), which are dependent upon constant ground water seepage

Tree canopy is Blue Mountains Ash (Eucalyptus oreades), which is rare and in the Blue Mountains found only around Katoomba

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

.

The headwaters of Katoomba Creek are forked from four upland gullies, one which has been dammed for water reservoir (Cascade Reservoir), and another starts near Twynam Street which forms the outer settlement area of Katoomba. It is just three kilometres upstream from the World Heritage Area – the boundary of which is rather arbitrary and should be here at the precious headwaters.

Yet despite the substrate and vegetation characteristics of the creek headwaters suiting those of a Blue Mountains Swamp, Blue Mountains Council’s chief housing development manager, Paul Weston, Executive Principal, Building & Construction Services on 13th February 2012 deemed that “the vegetation community across the site is consistent with the Eucalyptus oreades Open Forest community, and known variations of that community, and is not a hanging swamp.”

“The inspections confirmed that some basic features common to hanging swamps are present on the land, such as steep slopes and groundwater seepage which supports the occurrence of the fern species Pouched Coral Fern (Gleichenia dicarpa), which is also found in swamps. However, the absence of many typical Blue Mountains Swamp species, the presence of a prominent tree canopy, the absence of peat formation and the co-existence of the ferns with established and emerging sclerophyll shrub species, make this community inconsistent with that of the Blue Mountains Swamp Community.”

Furthermore, while the sheltered south easterly aspect, steep slope, the underlying geology and locally moist conditions provide a niche within the forested E. oreades- E. radiata – E. piperita community for ferns and other species to flourish in the wet conditions, the area does not support the usual suite of Blue Mountains swamp sedges, ground layer and shrub vegetation, nor the development of peat, nor is it wet enough to prevent the co-existence of other drier sclerophyll forest understory and canopy species in this vicinity.

The Proposed Housing Development Site at 121 Twynam Street Katoomba

The same Katoomba Creek Swamp – Tasman Flax-lily (Dianella tasmanica) in foreground

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

The Proposed Housing Development Site at 121 Twynam Street Katoomba

The same Katoomba Creek Swamp – Tasman Flax-lily (Dianella tasmanica) in foreground

Photo by Editor 20120128, licensed under ^Creative Commons, click image to enlarge

.

Blue Mountains Council’s Environmental Scientist and Environmental/Landscape Assessment Officer have inspected and assessed this swamp and deemed it not a swamp but a ‘wet forest‘.

Ed: What puritanical pretense!

.

This pristine vegetation community lies wholly within the riparian zone of the headwaters of Katoomba Creek (just metres away from the above photo). The underlying substrate is sandstone, ironstone and claystone bedrock forming a horizontal impermeable layer. The soil is ancient peaty sandy soil with organic matter that is poorly drained. It has constant groundwater causing waterlogged soil. The vegetation is a carpet of Pouched Coral Ferns, with a large cluster of King Ferns. It has Soft Twig Rush (Baumea rubiginosa), its Lepidosperma limicola (sedge grass in foreground). The tree canopy is Eucalyptus oreades which is common across Blue Mountains Swamps found at creek headwaters, but endemic only around Katoomba.

Is this more Swamp Selective Bias?

Indeed, the Blue Mountains Council ecological mapping assigned this site as a dry sclerophyll Eucalyptus piperita/ Eucalyptus sieberi forest. Woops.

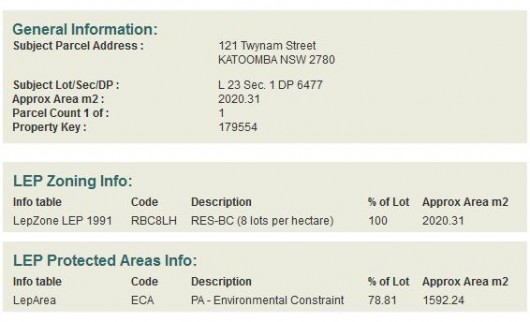

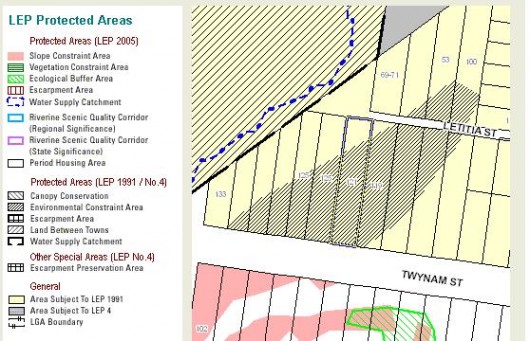

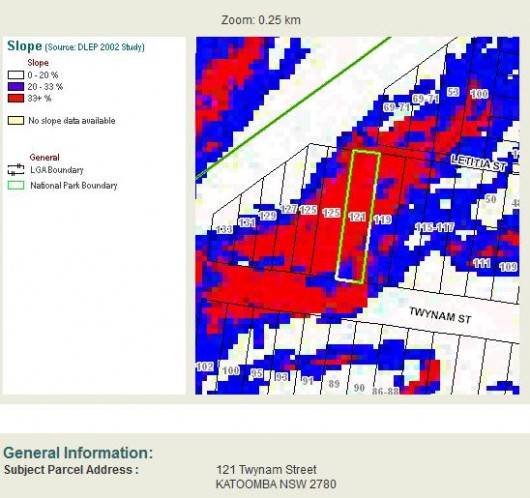

The Council judgment letter stated that this site is zoned under Local Environmental Plan (LEP) 1991 as Residential Bushland Conservation. But in fact, 80% of the site is zoned as a ‘Protected Area – Environmental Constraint‘ (see below extract). Woops.

The ‘Environmental Constraint Area‘ zoning under Local Enviropnment Plan 1991 for 121 Twynam Street (perimeter highlighted) covers 80% of the site from the street frontage..

LEP 1991 Protected Areas Objectives: Clause 7.2 Environmental Constraint Area

.

(a) To protect environmentally sensitive land and areas of high scenic value in the City (Ed: not that any reasonable person could possibly deem the Blue Mountains to be a ‘city’).

(b) To provide a buffer around areas of ecological significance. (Ed: Such as a pristine Blue Mountains Swamp)

(c) To restrict development on land that is inappropriate by reason of its physical characteristics or bushfire risk. (Ed: the site is Bushfire Risk Category 1)

.

121 Twynam Street is zoned a Category 1 Bushfire Risk

121 Twynam Street is zoned a Category 1 Bushfire Risk

.

The Slope of the site exceeds 33% grade, which exceeds the limits for the Council’s development criteria

The Slope of the site exceeds 33% grade, which exceeds the limits for the Council’s development criteria

.

LEP 1991 Clause 11.3 ‘Environmental Constraint Area’

.

“The Council shall not consent to development in a Protected Area – Environmental Constraint Area, unless it is satisfied, by means of a detailed environmental assessment, that the development complies with the objectives of the Protected Area that are relevant to the development and will comply with the Development Criteria in clause 10 that are relevant to the development.”

Council Judgment:

.

“In conclusion it is considered that the proposed dwelling and driveway have been designed and located to ensure that the development will not have a significant adverse environmental impact and is suitable for the site.”

.

[Sources: ‘Proposed dwelling at 121 Twynam Street, Katoomba” letter by Paul Weston, Executive Principal, Building & Construction Services, Blue Mountains Council’s Development, Health & Customer Services Department, 20120213, Ref: X/69/2010; Blue Mountains Council website – ‘Interactive Maps’, ^http://www.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/bmccmap/index.cfm]