Blue Gum Forest – in 2006 Parks let it burn

Tuesday, March 5th, 2013 Blue Gum Forest in 1931

An innocent time in fading history – when Platypus were plentiful, bred and swum freely in the Grose River

Blue Gum Forest in 1931

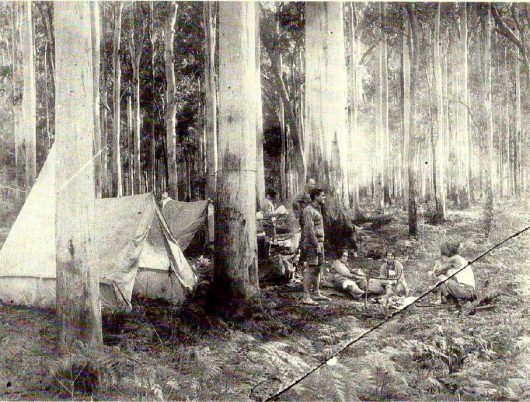

An innocent time in fading history – when Platypus were plentiful, bred and swum freely in the Grose RiverParty of Sydney Bush Walkers in Blue Gum Forest, circa October 1931 [Source: Photo by Alan Rigby, Blue Gum Forest Committee, from ‘Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness’ (1997), book by Andy Macqueen, p.256, click image to enlarge]

.

In 2006, the New South Wales (Government’s) Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) or ‘Parks‘, being delegated by the Australian Government for absolute responsibility for ecologically protecting the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (BMWHA), so under-resourced its firefighting effort as to deliberately let the Grose Valley burn out of control.

Senior management well knew, like their firefighting partners the Rural Fires Service, that legal and political accountabilty extended ONLY to protecting private properties and human lives. So this they did and so let 14,070 hectares of the Grose Valley and adjoining land burn. It saved them the cost and effort of future ‘hazard’ reduction.

Parks adopted a cost-saving abandonment strategy (making management look efficient) which it labels deliberate bushfire as ‘fire ecology‘ and so by deliberate under-resourcing of fire fighting against two documented ignitions to then let burn into the Grose Valley and the Blue Gum Forest. These two ignitions (1) a purported lightning strike on Burra Korain Ridge and (2) a deliberate RFS ‘hazard’ reduction burn along the south side of Hartley Vale Road – both outside the BMWHA, were the instigators of the 2006 Grose Fire.

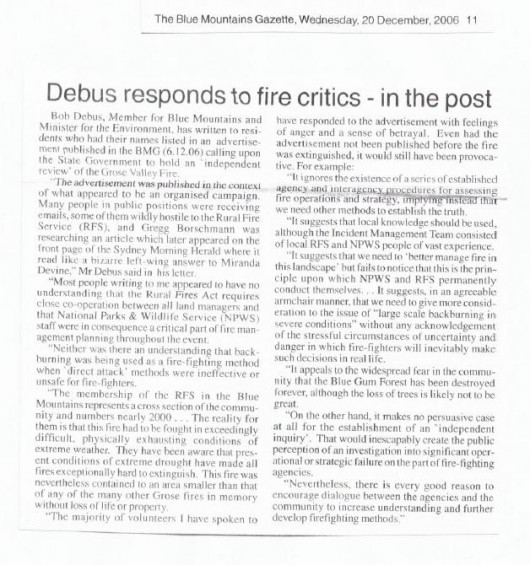

It was all hushed up, despite public calls for an independent public enquiry. Both the RFS Commissioner and Blue Mountains Local Member at the time said no to the public calls for an independent public enquiry. Why?

.

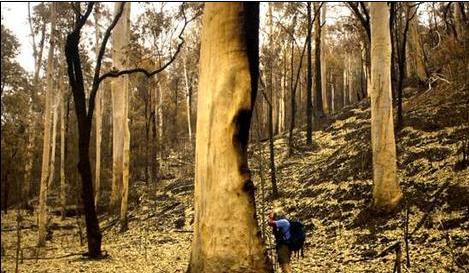

Grose Valley Fire aftermath at Govetts Leap, Blackheath

Grose Valley Fire aftermath at Govetts Leap, Blackheath[Photo by Editor 20061209, click image to enlarge, free in public domain]

.

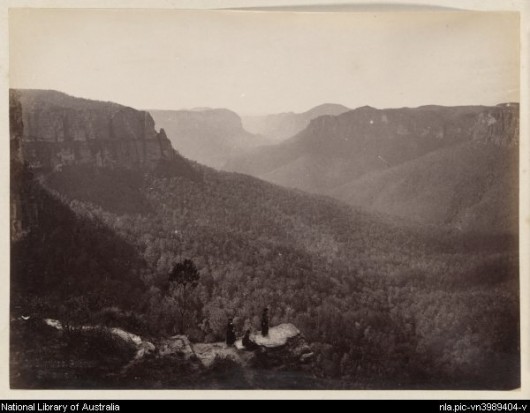

New South Wales colonists, once they stumbled across the spectacular Grose Valley deep in the Blue Mountains, were in awe in sublime wonder. So it was that initially that the Grose Valley as far back as in 1875 became reserved as a ‘national spectacle’.

But many wanted to dam it – ^Robber Barons and prevailing industrialist politicians of the times had the same view of ‘progress‘ being a colonial right and unquestioningly superior to Nature. They tried to put the railway through the Grose, to mine it, to log it or else to farm it; all so long as the vast ‘resource’ was not neglected for ‘progress‘.

.

Grose Valley, view from Govett’s Leap in 1886 by Charles Bayliss

Note the women in the foreground in the Victorian dress of the day

[Source: Part of Lindt, J. W. (John William), 1845-1926,

National Library of Australia, 1 digital photograph : b&w,

^http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3989404]

Grose Valley, view from Govett’s Leap in 1886 by Charles Bayliss

Note the women in the foreground in the Victorian dress of the day

[Source: Part of Lindt, J. W. (John William), 1845-1926,

National Library of Australia, 1 digital photograph : b&w,

^http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3989404]

.

Thankfully, this majestic Grose Valley and its ancient icon Blue Gum Forest were saved the axe in 1931. But is was only marginally due to the persistent campaigning efforts of a small dedicated group of bushwalkers passionate about saving this forest back even in the midst of The Great Depression.

If ever a case were not truer:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

~ American cultural anthropologist, Margaret Mead

.

‘The Blue Gum‘ was ultimately saved by the generous personal donation by allied bushwalker W.J. Cleary of £80 [perhaps $20,000 in today’s value *] to purchase the rights to the land from the pastoralist Clarrie Hungerford in February 1932..

Significantly, their dedicated act of environmental conservation is arguably the first environmental campaign in Australia’ history. ‘The Blue Gum‘ since then and for eighty years since has been affectionately known amongst environmentalists as ‘The Cradle of Conservation‘.

[Ed: * CALCULATION: In 1930, the average yearly wage for ordinary Australian workers was roughly £220, source: ^http://guides.slv.vic.gov.au/content.php?pid=14258&sid=95522. So given that today’s average yearly salary in Australia is about $56,000 (Source: ^http://www.abs.gov.au), the calculation is 80/220 * 56,000 = $20,000].

<<Everyone has been to the lookouts. Many have been to the Blue Gum Forest, deep in the valley– but few know the remote & hidden recesses of the labyrinth beyond. Here, an hour or two from Sydney, is a very wild place.

The Grose has escaped development. There have been schemes for roads, railways, dams, mines & forestry, but the bulldozers have been kept out. Instead, the valley became the Cradle of Conservation in New South Wales when it was reserved from sale in 1875 – an event magnificently reinforced in 1931 when a group of bushwalkers were moved to save the Blue Gum Forest from the axe.

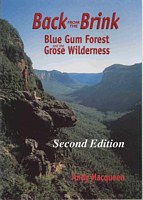

Local author, Andy Macqueen, has been an enthusiastic bushwalker and conservationist since the 1960’s. In 1997, he published his book, ‘Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness‘, aptly titled in telling the true story of how the Blue Gum Forest was saved from destruction.

Macqueen’s well researched book tells in detail the story of the whole Grose Wilderness experience and of the Blue Gum Forest rescue story in particular. It tells about the many different people who have visited this wilderness: Aborigines, explorers, engineers, miners, track builders, bushwalkers, canyoners, climbers…those who have loved it, and those who have threatened it.>>

Available from Megalong Books, Leura in the Blue Mountains

^http://shop.megalongbooks.com.au/bookweb/details.cgi?ITEMNO=9780646476957

^http://www.megalongbooks.com.au/

Available from Megalong Books, Leura in the Blue Mountains

^http://shop.megalongbooks.com.au/bookweb/details.cgi?ITEMNO=9780646476957

^http://www.megalongbooks.com.au/

.

Other books about the Blue Mountains:

^http://www.lamdhabooks.com.au/bluemountainscatalogue.htm.

Hazard Reduction Revenge

.

A decade later, in 1940 the Grose Valley was subjected to a bushfire; however its cause, circumstances and extent of damage are unknown by The Habitat Advocate.

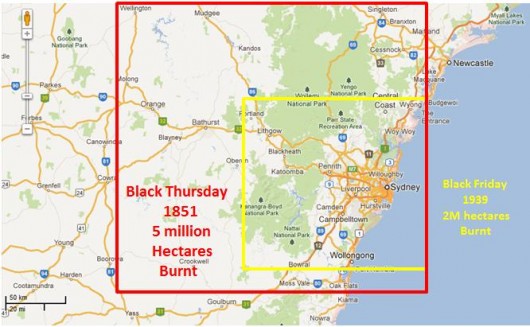

This bushfire occurred only a year after the devastating 1939 Bushfires of ‘Black Friday‘ across Victoria, which is collectively considered one of the worst natural bushfires (wildfires) in the world. Almost 20,000 km² (2 million hectares) was burnt, 71 people perished and several significant native forests were destroyed (Victorian Alps, Yarra Ranges, Otway Ranges, Grampians and Strzelecki Ranges) and the townships of Dromana, Healesville, Kinglake, Marysville, Narbethong, Warburton, Warrandyte, Yarra Glen, Hill End, Nayook West, Matlock, Noojee, Omeo, Woods Point, Pomonal and Portland.

The subsequent Royal Commission, under Judge L.E.B Stretton (known as the Stretton Inquiry), attributed blame for the fires to careless burning, such as for campfires and land clearing.

It was the second major bushfire tragedy since the 1851 Black Thursday Bushfires which wiped out 5 million hectares of Victoria.

. Bushfire Tragedy in aggregated geographical context.

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat?

Bushfire Tragedy in aggregated geographical context.

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat?

.

More recently a disturbing ‘bushphobic culture‘ has produced a need to burn it for its burning sake. One must wonder whether our society has indeed advanced, matured or just ‘progressed‘ its colonialism?

.

Grose Valley Bushfire of 25th October 2002

[Source: Image by Paul Cosgrave, National Library of Australia, 2003,

1 digital photograph : b&w.http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an24966058]

Grose Valley Bushfire of 25th October 2002

[Source: Image by Paul Cosgrave, National Library of Australia, 2003,

1 digital photograph : b&w.http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an24966058]

.

In 2006, the Grose Valley was incinerated in a massive firestorm and this time the fire ripped through the Blue Gum Forest..

.

. Firefighters watching the escalating bushfire incinerating the Grose Valley below

22 November 2006 – the day before the Grose Firestorm

Picture: Brad Newman, in The Australian.

Firefighters watching the escalating bushfire incinerating the Grose Valley below

22 November 2006 – the day before the Grose Firestorm

Picture: Brad Newman, in The Australian.

.

<<Residents in towns across NSW waited for the worst last night as bushfires burned thousands of hectares across the state and dry conditions were forecast for almost the entire continent for another week.

Spot fires from a 10-day-old bushfire burning in the Blue Mountains came within a few hundred metres of houses in Blackheath. Katoomba, Mount Tomah and Lawson and other towns in the region were also under threat from the worst bushfire in the nation.

“There was virtually no cloud over the entire continent,” said Julie Evans from the NSW Bureau of Meteorology of the dry conditions expected to continue across most of Australia in the coming week.

As mild weather and a cool change provided relief to firefighters in South Australia and Victoria, smoke from the Blue Mountains blaze, which was last night largely contained in the Grose Valley, rose more than 12km into the air, causing ash to fall on central Sydney and effectively creating its own weather system.

Watching from a helicopter above the flames, National Parks and Wildlife Service acting regional manager Kim De Govrik said the explosion as the fire crowned in the tree-tops around the Banks Wall cliff-face was “like a nuclear bomb going off”.

Sparks ignited fires up to 15km away, near Faulconbridge, home of Rural Fire Service Commissioner Phil Koperberg, who is directing the operation to contain the state’s fires.

“By tomorrow morning, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to expect that there will be additional fires around the countryside,” Mr Koperberg said yesterday.

About 2000 firefighters spent the day battling about 44 fires across NSW, five of which the RFS said it was unable to contain. Molong enjoyed a reprieve after a late wind shift caused a fire to change direction just 4km from the central-western town. Residents were relocated to a community centre last night, while an unoccupied house and vehicle were destroyed by the fire.

The RFS met residents in the Hawkesbury and Goulburn regions early last night to update them on the fires and what they can do to prepare their homes.

The bushfires also led to blackouts across Sydney. Just a week after the city endured its coldest November night in a century, the city sweltered through its third-hottest November day in 25 years — the official maximum temperature was 38.4C. Dozens of suburbs in the city’s west and southwest were affected by the outages, as were large sections of the CBD.

The NSW parliament was twice plunged into darkness as the power surges hit in the late afternoon, with the second one lasting several minutes.

Mild weather led the bushfire threat across South Australia to fall. CFS spokeswoman Krista St John said the state’s southeast had been hardest hit, with fires burning about 8500ha.

In Victoria, a cool change helped firefighters bring the state’s larger fires under control, although lightning strikes ignited several smaller fires in the west of the state.>>

.

[Source: ‘Fires and dry conditions have residents fearing the worst’, 20061123, by Dan Box and Simon Kearney; additional reporting by Padraig Murphy and AAP, The Australian newspaper, ^http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/fires-and-dry-conditions-have-residents-fearing-the-worst/story-e6frg6o6-1111112569927].

23 November 2006

14,070 hectares of precious Blue Mountains habitat incinerated

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat?

23 November 2006

14,070 hectares of precious Blue Mountains habitat incinerated

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat?

.

The home that Parks had it in for … the Blue Gum Forest’s fire-scarred trees,

some of which have graced the Grose Valley for hundreds of years.

The home that Parks had it in for … the Blue Gum Forest’s fire-scarred trees,

some of which have graced the Grose Valley for hundreds of years.A defacto hazard reduction burn. [Photo: Nick Moir, ^http://www.nickmoirphoto.com/]

.

<<More than 70 years ago this forest inspired the birth of the modern Australian conservation movement. Today Blue Gum Forest stands forlorn in a bed of ash.

But was it unnecessarily sacrificed because of aggressive control burning by firefighters focused on protecting people and property? That is the tough question being asked by scientists, fire experts and heritage managers as a result of the blaze in the Grose Valley of the upper Blue Mountains last month.

As the fate of the forest hangs in the balance, the State Government is facing demands for an independent review of the blaze amid claims it was made worse by control burning and inappropriate resources.

This comes against a backdrop of renewed warnings that Australia may be on the brink of a wave of species loss caused by climate change and more frequent and hotter fires. There are also claims that alternative “ecological” approaches to remote-area firefighting are underfunded and not taken seriously.

In an investigation of the Blue Mountains fires the Herald has spoken to experienced fire managers, fire experts and six senior sources in four agencies and uncovered numerous concerns and complaints.

* It was claimed that critical opportunities were lost in the first days to contain or extinguish the two original, separate fires.

* Evidence emerged that escaped backburns and spot fires meant the fires linked up and were made more dangerous to property and heritage assets – including the Blue Gum Forest. One manager said the townships of Hazelbrook, Woodford and Linden were a “bee’s dick” away from being burnt. Another described it as “our scariest moment”. Recognising the risk of the backburn strategy, one fire officer – before the lighting of a large backburn along the Bells Line of Road – publicly described that operation as “a big call”.

It later escaped twice, advancing the fire down the Grose Valley.

.

- Concerns were voiced about the role of the NSW Rural Fire Service Commissioner, Phil Koperberg.

- Members of the upper Blue Mountains Rural Fire Service brigades were unhappy about the backburning strategy.

- There were doubts about the mix and sustainability of resources – several senior managers felt there were “too many trucks” and not enough skilled remote-area firefighters.

- Scientists, heritage managers and the public were angry that the region’s national and international heritage values were being compromised or ignored.

- There was anecdotal evidence that rare and even common species were being affected by the increased frequency and intensity of fires in the region.

- Annoyance was voiced over the environmental damage for hastily, poorly constructed fire trails and containment lines, and there were concerns about the bill for reconstruction of infrastructure, including walking tracks.

.

The fire manager and ecologist Nic Gellie, who was the fire management officer in the Blue Mountains for the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service during the 1980s and ’90s, says the two original fires could have been put out with more rapid direct attack.

“Instead, backburning linked up the two fires and hugely enlarged the fire area … what we saw would be more accurately described as headfire burning, creating hot new fire fronts. While it protected the town of Blackheath, the plateau tops burnt intensely – and that created new problems both for management of the fire and the protection of biodiversity.

“When extreme fire weather, hot days and high winds arrived as predicted, the expanded fire zone was still not fully contained – and that was the cause of most of the high drama and danger that followed.”

In that dramatic week, Mr Gellie confronted Mr Koperberg with his concerns that the commissioner was interfering with the management of the fire by pushing hard for large backburns along the northern side of towns in the Blue Mountains from Mount Victoria to Faulconbridge, along what is known in firefighting circles as the “black line”.

The Herald has since confirmed from numerous senior sources that “overt and covert pressure” from head office was applied to the local incident management team responsible for fighting the fire.

There were also tensions relating to Mr Koperberg’s enthusiasm for continuation of the backburning strategy along the black line – even when milder weather, lower fuel levels and close-in containment were holding the fire.

Several sources say the most frightening threat to life and property came as the fire leapt onto the Lawson Ridge on “blow-up Wednesday” (November 22) – and that those spot fires almost certainly came from the collapse of the convection column associated with the intensification of the fire by the extensive backburns.

.

The Herald has also confirmed that:

- The original fire lit by a lightning strike near Burra Korain Head inside the national park on Monday, November 13, could not be found on the first day. The following day, a remote area fire team had partly contained the fire – but was removed to fight the second fire. The original fire was left to burn unattended for the next couple of days;

.

- An escaped backburn was responsible for the most direct threat to houses during the two-week emergency, at Connaught Road in Blackheath. However, at a public meeting in Blackheath on Saturday night, the Rural Fire Service assistant commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons played down residents’ concerns about their lucky escape. “I don’t want to know about it. It’s incidental in the scheme of things.”

.

Mr Koperberg, who is retiring to stand as a Labor candidate in next year’s state elections, rejected the criticisms of how the fire was fought. He told the Herald: “The whole of the Grose Valley would have been burnt if we had not intervened in the way we did and property would have been threatened or lost. We are looking at a successful rather than an unsuccessful outcome.

“It’s controversial, but this is world’s best backburning practice – often it’s the only tool available to save some of the country.”

The commissioner rejected any criticism that he had exerted too much influence. “As commissioner, the buck stops with me. I don’t influence outcomes unless there is a strategy that is so ill-considered that I have to intervene.”

Mr Koperberg said it was “indisputable and irrefutable” that the Blue Mountains fire – similar to fires burning now in Victoria – was “unlike any that has been seen since European settlement”, because drought and the weather produced erratic and unpredictable fire behaviour.

The district manager of the Blue Mountains for the Rural Fire Service, Superintendent Mal Cronstedt, was the incident controller for the fire.>>

.

[Source: ‘The ghosts of an enchanted forest demand answers’, 20061211, by Gregg Borschmann, Sydney Morning Herald, p.1, ^http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/the-ghosts-of-an-enchanted-forest-demand-answers/2006/12/10/1165685553891.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap2].

Grose Valley’s bushphobic habitat incinerated

because in the minds of Parks and the Rural Fire Service it was a fuel hazard

Click image to enlarge,

Photo by Editor 20070106, free in public domain

Grose Valley’s bushphobic habitat incinerated

because in the minds of Parks and the Rural Fire Service it was a fuel hazard

Click image to enlarge,

Photo by Editor 20070106, free in public domain

.

<<A bushfire scars a precious forest – and sparks debate on how we fight fire in the era of climate change, writes Gregg Borschmann.

The ghosts of an enchanted forest demand answers

“Snow and sleet are falling on two bushfires burning in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney.”

ABC Radio, November 15: The news report was almost flippant, something that could happen only in Dorothea Mackellar’s land of drought and flooding rains. Later that evening, two weeks from summer, Sydney had its coldest night in more than a century.

Over the past month – as an early summer collided with a late winter and a decade-long drought – NSW and Victoria have battled more than 100 bushfires.

But of them all, last month’s Blue Mountains blaze reveals tensions and systemic problems that point to a looming crisis as bushfire fighters struggle to protect people, property, biodiversity and heritage values in a world beset by climate change.

The tensions have always been there – different cultures, different ways of imagining and managing the landscape. Perhaps they are illustrated by a joke told by two Rural Fire Service crew in the Blue Mountains. “How does the RFS put out a fire in your kitchen? By backburning your sitting room and library.” The joke barely disguises the clash between the imperative of saving lives and homes, and the desire to look after the land, and the biodiversity that underpins our social and economic lives.

For fire managers, whose first priority will always be saving people and property, the equation has become even more tortured with a series of class actions over fires in NSW and the ACT. As one observer put it: “These guys are in a position where they’re not going to take any chances. No one will ever sue over environmental damage.”

For bushfire management the debate tentatively started a couple of decades ago. The challenge was to do what poets, writers and painters have long grappled with – coming to terms with a country whose distinctiveness and recent evolutionary history have been forged in fire.

Drought and climate change now promise to catapult that debate to centre stage.

It is perhaps no accident that such a defining fire has occurred in one of the great amphitheatres of the Australian story, the Grose Valley in the upper Blue Mountains. Charles Darwin passed by on horseback in 1836, and described the valley as “stupendous … magnificent”.

The Grose has long been a microcosm of how Australians see their country. In 1859 some of the first photos in Australia were taken in the valley. Proposals for rail lines and dams were forgotten or shelved. The first great forest conservation battle was fought and won there in 1931-32.

But now the valley is under threat from an old friend and foe – fire.

Ian Brown has worked on dozens of fires in the Blue Mountains. He is a former operations manager for the National Parks and Wildlife Service.

“All fires are complex and difficult, and this sure was a nasty fire … But we need lots of tools in the shed. Those hairy, big backburns on exposed ridges so close to a blow-up day with bad weather surprised me. Frightened me even.”

For Brown, even more worrying is the trend.

“Parts of the Grose have now burnt three times in 13 years and four times in 24 years. Most of those fires started from arson or accident. Many of the species and plant communities can’t survive that sort of hammering.”

Ross Bradstock, a fire ecologist, agrees. Professor Bradstock is the director of the new Centre for the Environmental Risk Management of Bushfires at the University of Wollongong, which is funded by the Department of Environment and Conservation and the Rural Fire Service. He says Australia stands out as one of the countries whose vegetation may be most affected by climate change.

Bradstock says that in south-eastern Australia the potential for shifts in fire frequency and intensity are “very high … If we’re going to have more drought we will have more big fires.”

But the story is complicated and compounded by the interaction between drought and fire. The plants most resistant to fire, most able to bounce back after burning, will be most affected by climate change. And the plants that are going to be advantaged by aridity will be knocked over by increased fire frequency. “In general, the flora is going to get whacked from both ends – it’s going to be hit by increased fire and climate change. It’s not looking good.”

Wyn Jones, an ecologist who worked for the wildlife service, says the extremely rare drumstick plant, Isopogon fletcheri, is a good example. There are thought to be no more than 200 specimens, restricted to the upper Grose. Last week, on a walk down into the Blue Gum Forest, Jones found three – all killed by the fire.

The NSW Rural Fire Service Commissioner, Phil Koperberg, has been a keen supporter of Bradstock’s centre. Asked if he agreed with the argument that the Grose had seen too much fire, Mr Koperberg replied: “It’s not a comment I disagree with, but had we not intervened in the way we did, the entire Grose Valley would have been burnt again, not half of it.”

The great irony of the fire is that it was better weather, low fuels and close-in containment firefighting that eventually stopped the fire – not big backburns.

Remote area firefighting techniques have been pioneered and perfected over recent decades by the wildlife service. In 2003 a federal select committee on bushfires supported the approach. It recommended fire authorities and public land managers implement principles of fire prevention and “rapid and effective initial attack”.

Nic Gellie, a fire ecologist and former fire manager, has helped the wildlife service pioneer ecological fire management. The models are there – but he says they have not been used often enough or properly.

Doubts have been expressed about the sustainability of the current remote area firefighting model. It is underfunded, and relies on a mix of paid parks service staff and fire service volunteers. Most agree the model is a good one, but not viable during a longer bushfire relying on volunteers.

The Sydney Catchment Authority pays $1 million for Catchment Remote Area Firefighting Teams in the Warragamba water supply area. It has always seemed like a lot of money. But it looks like a bargain stacked against the estimated cost of $10 million for the direct costs and rehabilitation of the Grose fire.

Curiously, one unexpected outcome of the great Grose fire may be that the valley sees more regular, planned fire – something the former wildlife service manager Ian Brown is considering.

“If climate change means that the Grose is going to get blasted every 12 years or less, then we need more than just the backburning strategy. We need to get better at initial attack and maybe also look at more planned burns before these crises. But actually getting those burns done – and done right – that’s the real challenge.”

It may be the only hope for Isopogon fletcheri.

Asked if he would do anything differently, Mr Cronstedt answered: “Probably.” But other strategies might have also had unknown or unpredictable consequences, he said.

Jack Tolhurst, the deputy fire control officer (operations) for the Blue Mountains, said: “I am adamant that this fire was managed very well. We didn’t lose any lives or property and only half the Grose Valley was burnt.”

Mr Tolhurst, who has 50 years’ experience in the Blue Mountains, said: “This fire is the most contrary fire we have ever dealt with up here.”

John Merson, the executive director of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute, said fire management was being complicated by conditions possibly associated with climate change.

“With increased fire frequency and intensity, we are looking at a fundamental change in Australian ecosystems,” he said. “We will lose species. But we don’t know what will prosper and what will replace those disappearing species. It’s not a happy state. It’s a very tough call for firefighters trying to do what they think is the right thing when the game is no longer the same.

“What we are seeing is a reflex response that may no longer be appropriate and doesn’t take account of all the values we are trying to protect.”>>

.

[Source: ‘ The burning question’, 20061211, by Gregg Borschmann (producer for ABC Radio National), Sydney Morning Herald, p.10, ^http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/the-burning-question/2006/12/10/1165685553945.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap1].

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat?