Fraser Island: Bevan Tourism dictates Dingo Culls

Saturday, December 22nd, 2012 Inky

A pure Fraser Island Dingo

Inky

A pure Fraser Island Dingopersecuted by a colonial-mindset Queensland Government

..left ear ‘tagged’ by rangers and permanently damaged ..since shot by same rangers.

.

Wildlife-based Tourism Exploitation

.

<<Wildlife-based tourism is a major tourism activity and is increasing in popularity. For many international tourists visiting Australia, viewing Australian wildlife forms a major part of their visit (Fredline & Faulkner 2001). For domestic tourists, viewing wildlife and sometimes interacting with it is also an important activity, and it caters for specialists and generalists alike.>>

[Source: ‘Economics, Wildlife Tourism and Conservation: Three Case Studies’, 2004, by Clem Tisdell and Clevo Wilson, CRC for Sustainable Tourism, commissioned by the Australian Government (i.e. taxpayer funded), p.1, ^http://www.crctourism.com.au/WMS/Upload/Resources/bookshop/FactSheets/fact%20sheet.pdf].

But it is this ‘Wildlife-based Tourism‘ industry sector where Australian tourism has taken on a dark side. The industry and the revenue and profits it generates are being used by Australian state governments to justify greater destruction of Australia’s fragile ecosystems. This innocuous euphemism is exploited by the Queensland Tourism industry to belie the true destructive ecological impacts of ‘Nature Tourism‘ or ‘Ecotourism‘.

This is like painting a bulldozer green and all subsequent use labelled as ‘eco-bulldozing‘.

Badge d’Exploitation

.

.At least 50% of a tourism operator’s offerings must have a Nature-based focus

and some vague notion of ‘sustainability’ principles.

Pay our fee…et voilà!’ – eco-certification!

[Read More: EcoTourism Australia (a private company), ^http://www.ecotourism.org.au/]

Badge d’Exploitation

.

.At least 50% of a tourism operator’s offerings must have a Nature-based focus

and some vague notion of ‘sustainability’ principles.

Pay our fee…et voilà!’ – eco-certification!

[Read More: EcoTourism Australia (a private company), ^http://www.ecotourism.org.au/]

.

But the most disturbing trend is that even the state government custodians entrusted with ecological protection and conservation, the variously named National Parks and Wildlife Service agencies, have placed the aims of recreation and tourism at a higher management priority than their core function of ecological protection and conservation.

Perhaps this exploitative trend is no more prevalent than across Queensland’s Natural ecology, which is ‘managed’ by the Queensland Government’s Department of National Parks, Recreation and Racing. About Us: <<The department manages national parks and their use and enjoyment by all Queenslanders; encourages active lifestyles by providing recreational and sporting opportunities; and manages the racing industry which directly employs 30,000 Queenslanders.>>

<<Queensland’s parks and forests underpin the State’s thriving nature tourism industry. They attract millions of overseas and Aussie visitors each year and contribute billions of dollars to the Queensland economy. Tourists visiting Queensland’s national parks spend $4.43 billion annually—28% of all total tourist spending in Queensland.>>

[Source: ‘Commercial tourism on parks’, Department of National Parks, Recreation and Racing, Queensland Government, ^http://www.nprsr.qld.gov.au/tourism/]. Queensland Government’s Coat of Arms

Queensland Government’s Coat of Arms

.

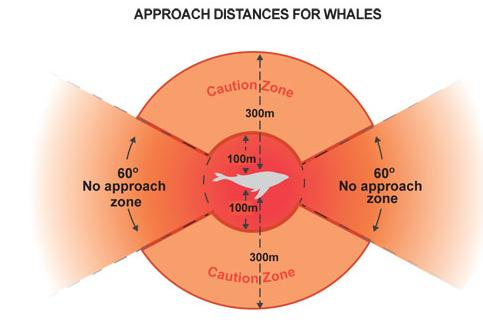

Situated along Queensland’s central coast, World Heritage Fraser Island is a case in point. Here, tourism visitation has become unsustainable to the point of driving the island’s ecological destruction. The Queensland Government’s tourism marketing brands the area the Fraser Coast to take in whale watching in Hervey Bay, Reef diving and Fraser Island. The exploitation of Wildlife-based Tourism is focused on maximising visitation numbers, as if bureaucratic commissions are earned according to visitation numbers.

Commercial tourism unethically/illegally too close to a Humpback Whale

Yet this image appears on the official Queensland Government tourism website (20121222)

[Source: ^http://www.queenslandholidays.com.au/destinations/fraser-coast/fraser-coast_home.cfm]

Commercial tourism unethically/illegally too close to a Humpback Whale

Yet this image appears on the official Queensland Government tourism website (20121222)

[Source: ^http://www.queenslandholidays.com.au/destinations/fraser-coast/fraser-coast_home.cfm]

.

The Australian National Guidelines for Whale and Dolphin Watching 2005

[Source: Australian Government,

^http://www.environment.gov.au/coasts/species/cetaceans/whale-watching/]

The Australian National Guidelines for Whale and Dolphin Watching 2005

[Source: Australian Government,

^http://www.environment.gov.au/coasts/species/cetaceans/whale-watching/]

.

Fraser Island’s native top order predator, the Dingo, has been on Fraser Island for at least 1000 years. But the Dingo and its fragile ecology are being persecuted and destroyed by the Queensland Government because the prevailing 20th Century exploitative attitude is that Bevan Tourism generates income; Dingoes don’t. The wildlife tourism promotion of Fraser Island by the Queensland Government has exploited ‘the thrill of seeing a dingo ‘in the wild’ and used the Dingo as a major tourism drawcard.

Dingo Tourism on Fraser Island is actively encouraged by the Queensland Government

Fraser Island Discovery, with its dingo logo shown above, won a recent Queensland Government Tourism Award

Dingo Tourism on Fraser Island is actively encouraged by the Queensland Government

Fraser Island Discovery, with its dingo logo shown above, won a recent Queensland Government Tourism Award

.

Bevan Tourism

.

Bevan Tourism is the exploitative, destructive and disrespectful tourism that appeals to the uncouth, loud mouthed, red neck, yobbo, hoon element of Queensland society.

Particular to parochial Queensland, the ‘Bevan‘ is characteristically a young poorly educated Caucasian male usually very thin, or sometimes quite fat with the onset of manboobs, and displaying the clichéd antisocial behaviours such as hooliganism, swearing, reckless driving, alcoholism, Winnie blue smoking (with spare fag ducked behind ear), XXXX/Bundy Rum drinking, and habitually louting around in front of sheilas.

Bevans at Play

Bevans at Play

.

Bevans are best avoided, especially at social gatherings, sports events, beaches and at campsites. (See also: ‘Bogan’ (Melbourne), ‘Westie’ (Sydney), ‘Ned’ (Glasgow), ‘Yob’, ‘Bozo’, ‘Low-Life’).

A Queenslander Bevan, royally succumbed to recreational stupor

A Queenslander Bevan, royally succumbed to recreational stupor

.

Bevan Tourism has taken cultural hold over a few popular holiday destinations along the Queensland coast. Over the past few generations, Bevans mainly from metropolitan Brisbane have particularly targeted the Gold Coast, Maryborough and Fraser Island.

Queensland’s Bevan Tourism most exquisitely expressed here by Fraser Explorer Tours

Queensland’s Bevan Tourism most exquisitely expressed here by Fraser Explorer Tours– on Fraser Island

.

Fraser Island, despite being recognised and listed as a Natural World heritage site since 1992, each holiday season is invaded by Bevan Tourism, targeted especially over Easter. In part this is because, Queensland Government’s own state tourism department, in cahoots with its national park agency, has marketed Fraser Island for ‘adventure’, ‘parties’, and ‘families’. Fraser Island’s international listing has been exploited as a tourism drawcard, more so than properly conserved for its internationally important remnant ecosystems, wildlife and flora.

The disturbing trend is that the in mindset of parochial Queensland Tourism, Bevan Tourism is marketed as an equitable right for all people, and that Nature exists in an anthropocentric sense simply to serve that right. This attitude to ecology is retrograde and straight out of the ancient Old Testament:

.

<<And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.>>

[Source: Book of Genesis, 1:26, Christian Bible, Old Testament].

The ‘Dominion Theology’ worldview of Nature

It’s there to be used, feared, exploited, persecuted, poached, butchered, eaten, enslaved, raped, shot, hacked, played with as sport, made extinct.

The ‘Dominion Theology’ worldview of Nature

It’s there to be used, feared, exploited, persecuted, poached, butchered, eaten, enslaved, raped, shot, hacked, played with as sport, made extinct.

.

Fraser Island heritage avoids Conservation

.

Pure Fraser Island

[Source: Australian Geographic,

^http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/view-image.htm?index=8&gid=9642]

Pure Fraser Island

[Source: Australian Geographic,

^http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/view-image.htm?index=8&gid=9642]

.

Fraser Island, the world’s largest sand island, was afforded UNESCO World Heritage status because it satisfied the following three selection criteria:

- Superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance (Natural Criterion 7)

- Outstanding examples which represent major stages of earth’s history, including the record of life, significant ongoing geological processes in the development of landforms, or significant geomorphic or physiographic features (Natural Criterion 8 )

- Outstanding examples representing significant ongoing ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems and communities of plants and animals (Natural Criterion 9)

.

Despite these recognise over-arching natural values, tourism and its negative impacts have been allowed to snowball in visitation volume since heritage listing in 1992, while custodial management has allowed the same values to deteriorate.

What has been conspicuously overlooked is proper recognition of Fraser Island’s status under UNESCO Natural Criterion 10, for surely Fraser Island ‘contains the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation.’

The custodianship of such valuable World Heritage properties across Australia is the ultimate responsibility of the Australian Government.

While Australia’s World Heritage properties are legally protected under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), conveniently responsibility for that protection is rather half-hearted since the Australian Government delegates management of all of them to the lesser state governments, which have considerably less resources and demonstrably less interest in delivering UNESCO-standard ecological conservation management.

^United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

^United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

.

The Queensland Government for instance, currently lumps Fraser Island management under its Department of National Parks, Recreation, Sport and Racing. Clearly, the attitude of the Queensland Government to World Heritage and National Parks under its custodial responsibility exists for human recreational benefit and enjoyment – along with sport and racing.

.

Fraser Island’s Record of Exploitation

.

Prior to 1992, Fraser Island was industrially abused; mined for minerals and sand (1966-1989) and logged for old growth Turpentine timber (Syncarpia glomulifera) for over 130 years. [Read: >‘Impacts of Logging on Fraser Island’]Fraser Island’s ecosystems (its rainforests, Wallum woodlands, freshwater dune lakes and coastal dunes) came close to irreversible annihilation by over-exploitation by these two industries and condoned for such by successive Queensland governments.

Since logging and mining were stopped (only from international embarrassment), Queensland’s Tourism Industry has been supplanted as Fraser Island’s main threat, yet consistently encouraged and funded doggedly by a 20th Century mindset Queensland Government.

Wild Dingo

Australia’s native top order predator

Wild Dingo

Australia’s native top order predatorpromoted by the Queensland Government as a tourism drawcard to Fraser Island culled by the Queensland Government from 300 down to just 100 individuals shot by the Queensland Government if ‘aggressive’ (wild)

.

<<Fraser Island tourism has been burgeoning for decades. In 1971 the number of visitors to Fraser Island doubled from 5,000 in the previous year to 10,000 as a result of the publicity surrounding the sandmining controversy. It has steadily increased ever since. By 1999 it had reached over 300,000 visitors.>>

Current statistics for Fraser Island visitation are not readily published by the Queensland Government, but it is estimated that around 500,000 visitors, many from overseas, visit Fraser Island each year. [Source: ‘Concerns heightening for Fraser Island’s dingoes’, 2009, by Nick Alexander, in Ecos Magazine, ^http://www.ecosmagazine.com/view/journals/ECOS_Print_Fulltext.cfm?f=EC151p18]

Hummers catering for Bevan Tourism

– on Fraser Island

Hummers catering for Bevan Tourism

– on Fraser Island

.

<<For Lake McKenzie (Fraser Island) in particular, extremely high visitation levels over the course of summer are ultimately likely to influence the ecology of the system, particularly if a considerable proportion of visitors add nutrients to the lake, either through urination, washing or bathing activities (Strasinger 1994, Butler et al. 1996).>>

.

[Source: ‘Effects of Tourism on Fraser Island Dune Lakes‘, 2004, by Wade Hadwen et al. Read the complete paper below under the heading ‘Read more about Tourism Impacts on Fraser Island‘].

The Four Main Adverse Impacts of Tourism on Fraser Island

.

1. Target Destinations (high concentration visitation)

.

Certain Fraser Island areas are identified and marketed by tourist interests with the result that they draw tourists to them like bees to a honey pot even to the extent that they become needlessly degraded and overused. Eli Creek, Lake McKenzie and Central Station are such sites.

Daily hundreds of tourists from the Noosa area spend needless hours to drive past equally outstanding natural features in the Cooloola National Park so that commercial tour operators can capitalize on the “marketing of these well-known products”. This focus is unsustainable.

Such sites are being overused and yet tourists are reluctant to be redirected to other alternative areas which could sustain some increase in visitation.

Tourist saturation of Eli Creek, Fraser Island

(Dingo habitat designated off-limits to Dingoes)

Tourist saturation of Eli Creek, Fraser Island

(Dingo habitat designated off-limits to Dingoes)

.

2. Means of Access

.

Once tourism becomes established, it is difficult to change.

Tourist guide books tend to be based upon past experience. Recommendations to intending visitors are largely based on such past practice. Thus although there are better ways to see Fraser Island than in largely lumbering four wheel drive buses or self of four wheel drive vehicles, this method of visitation has become so entrenched that it is difficult to change.

The most serious adverse environmental impacts now being experienced on Fraser Island are result of this form of transportation.

Ban 4WDs from Fraser Island

Change the 20th Century culture!

Ban 4WDs from Fraser Island

Change the 20th Century culture!

.

3. “Traditional” Visitation Practices

.

It takes very little time for modern society to claim that certain practices are so “traditional” that practitioners claim they can’t be changed.

This has been used by commercial fishers to demand to camp in the same site contrary to the Recreation Areas Management Act and to have vehicular access to beaches closed to other vehicular traffic.

Likewise the “tradition” of free range camping has become so entrenched that although this practice has been shown to be unsustainable there is a reluctance to phase it out despite compelling evidence that this form of tourism should be ended. Similar conservatism allows Fraser Island tourists to continue to squander resources and degrade the environment through open camp-fires.

.

4. Surface Disturbance

.

On Fraser Island, the impact of surface disturbance of any sort is more critical than most other natural areas which have a much more robust substrate (ground surface).

The susceptibility of the substrate to any disturbance magnifies the impacts of tourism on Fraser Island more than most other natural areas. (Coral reefs and semi-arid areas with cryptobionic crusts may be as susceptible to disturbance). The reason for this fragility is due to the fact that exposed sand surfaces in vegetated areas of Fraser Island have a very high degree of water repellence which makes them very susceptible to water erosion. Vegetated sand surfaces are much less susceptible.

If the visitors can be carried in such a way that they do not disturb the substrate surface by such means as board walks or by light rail, then the surface disturbance and thus the environmental impact of visitation is contained and reduced.>>

.

.

Further Tourism Impacts

.

5. Erosion of Wilderness Values

.

Tourism erodes wilderness values through its infrastructure — motor vehicles, roads, modern buildings and the sounds of modern engines. The increasing penetration of more people into parts of the island previously exempt from intense visitation erodes wilderness. Aircraft overflying remoter parts of Fraser Island and other intrusive modern noise also erodes wilderness values.

.

6. Spread of Injurious Agents

.

Injurious agencies which impact on other values of Fraser Island include the spread of weeds, feral animals and pests, new pathogens, wild fires and litter. Tourism has the potential to facilitate the introduction and spread of these injurious agencies. In the end the impact of injurious agencies resulting from tourism have a greater potential to degrade Fraser Island than some other industries.

.

7. Diversion of Management Resources

.

Managing tourism is responsible for diverting much of Fraser Island’s very limited resources from natural resource management (control of fires, weeds, feral animals etc. and resource monitoring) to recreation management (including access, waste management, behaviour control, provision of infrastructure, maintenance for roads, etc.). Tourism produces a great deal of waste and human waste and this is resulting in some water pollution particularly as a result of inadequate treatment of sewage.

Increasing numbers of tourists also impede natural resource management strategies such as fire and dingo management because of the high priority given to public safety and property protection over resource management and protection.

.

8. Perversion of political priorities

.

Pandering to perceived tourist demands has resulted in political decisions which have over-ridden the Management Plan for Fraser Island such as relocating the Toyota Fishing Expo and reopening the dangerous Orchid Beach airstrip. Many politicians are motivated more by pursuing popularity than with implementing a Management Plan which some vocal dissidents with vested interests disagree with.

A Queensland Tourism ideal image for Fraser Island

Maximising 4WD tourist numbers!

A Queensland Tourism ideal image for Fraser Island

Maximising 4WD tourist numbers!.

Motor Vehicle Impacts

4WD road widening of Fraser Island

4WD road widening of Fraser Island

.

The impact of four wheel drives on Fraser Island is extremely significant; affecting roads, wildlife, habitat and recreation amenity.

.

9. Roads

.

The largest impact is on the roads. Road traffic accelerates erosion. During every heavy downpour of rain thousands of tonnes of sand wash off the roads to fill lake basins and streams with sediment and smother many natural habitats. In February 1999, over two metres of sand was deposited at the intersection of the Pile Valley and Wanggoolba Creek Road burying a large stump. Sand from adjacent roads is being sluiced into Lake McKenzie, Lake Allom, Lake Boomanjin, Lake Birrabeen and more.

Opening of the canopy over the roads results in desiccation resulting in considerable changes to the micro-flora and a reduction of ^epiphyte numbers.

.

10. Impacts on Wildlife

.

Back in 1991, when Fraser Island was listed for its natural world heritage values, its Dingo population was about 300 individuals and believed to be ‘the largest genetically

unhybridised population on the east coast of Australia.

But Bevan Tourism saw increasing numbers of young families recklessly venturing into the wild Dingo’s habitat and feeding grounds. During one of the busy tourist holiday times, Christmas summer holidays, a young child was mauled by a dingo, and an ignorant vengeful media campaigned to demonise the Dingo. The media venom fabricated the term ‘Dingo Superpack‘.

During the following six years, the Queensland Government ordered the killing of over a hundred Dingoes on Fraser Island. In 2001, a nine-year-old schoolboy, Clinton Gage, was fatally mauled by a Dingo, which sparked another media Dingo witch-hunt, and a further 32 Dingoes were killed within a matter of a few weeks by the Queensland Government.

An infant (4 years old) was badly bitten by a Dingo on Fraser Island in April 2007 and another 3 year in April 2011. Both incidents occurred during the popular Bevan Tourism Easter holidays. Both involved irresponsible parents. In July 2012, a drunken German tourist, sleeping it off alone on an isolated bush track at night, was attacked by a Dingo. He was part of Bevan Tourist group organised by the Rainbow Beach Adventure Company.

Despite the protection status of the Dingo in its native habitat in a listed World Heritage Area, the Queensland Government has ignored the wildlife values and rights in favour of perpetuating Bevan Tourism rights. It has become standard management practice for the Queensland Government’s Parks and Wildlife Service to shoot kill any ‘aggressive’ animal or animal that ‘shows no fear of humans’ – that is, Dingoes.

Dingo pup tagged by rangers on Fraser Island, November 2012

Another ear permanently damaged

Dingo pup tagged by rangers on Fraser Island, November 2012

Another ear permanently damaged

.

Since 2009, researcher Dr Luke Leung from Queensland University, has feared the population has been reduced to around 100 animals and their genetic viability over the long term is being compromised.

In addition, shore bird numbers have been decimated by the unchecked growth of four wheel drive beach traffic. Oyster catchers, Red-capped dotterels and Beach thick-knees have been most affected.

.

11. Eroding Habitat

.

Roads occupy space, a space which takes a long time to revegetate after the roads cease to be used. Roads also act as barriers to the movement of wildlife. Distribution of many ant species and frogs is affected by roads. Some won’t cross roads to identical habitat on the other side.

As a consequence of habitat destruction, the availability of natural prey of the Dingo, such as bandicoots, rats, echidnas, fish, turtles and skinks, has declined. Dingoes have been forced to scavenge around tourist campsites for human food and garbage. Tourists ignorantly feeding Dingoes has encouraged Dingoes to become less independent upon reduced natural prey and more dependent on tourists, which has adversely altered the natural food chain only the island.

.

12. Pollution

.

Now there evidence is starting to appear that vegetation adjacent to “black holes” in the roads is suffering.

.

13. Noise

.

The aesthetic impact of noise is well known and understood yet it is largely ignored. The impact of the noise from traffic on the road above Wanggoolba Creek on the walking track beside this icon of Fraser Island significantly degrades this experience.

.

14. Distortion of Priorities

Populist politicians condone novel commerce ahead of novel solutions

Populist politicians condone novel commerce ahead of novel solutions

.

Because so much of Fraser Island tourism is vehicle based, roads have been cannibalistic, consuming a disproportionate share all the financial and staff resources.

This stopped any progress towards a walking track management plan for the island for more than six years. Vehicle based tourism has also been responsible for preventing closing tracks due to be closed under the Management Plan for more than 6 years. Preoccupation with roads has stalled progress towards the establishment of a more ecologically sustainable light rail proposal.>>

.

[Sources: ‘Values of Fraser Island Tourism’, Fraser Island Defenders Organisation (FIDO), ^http://www.fido.org.au/values-of-fraser-tourism.html; ‘Concerns heightening for Fraser Island’s dingoes’, 2009, by Nick Alexander, in Ecos Magazine, CSIRO Publishing, Australia. ^http://www.ecosmagazine.com/view/journals/ECOS_Print_Fulltext.cfm?f=EC151p18].

Read more about Tourism Impacts on Fraser Island

.

[a] ‘Fraser Island Discussion Paper and Recommendations‘, Aug 2010, Queensland Liberal National Party (LNP) while in opposition (in government since March 2012), ^http://savefraserislanddingoes.com/pdf/Fraser%20Island%20Discussion%20paper%20and%20recommendations%2023.8.10.pdf, [>Read Report 570kb, PDF]

.

[b] ‘Effects of Tourism on Fraser Island Dune Lakes‘, 2004, by Wade Hadwen, Angela Arthington, Stuart Bunn and Thorsten Mosisch, Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre, research project funded by the Australian Government (i.e Australian taxpayers), ^http://www.crctourism.com.au/wms/upload/images/disc%20of%20images%20and%20pdfs/for%20bookshop/documents/hadwen21001_fraserisdlakes.pdf

Brief Abstract:

<<In light of the rapidly growing tourism industry in the region, excessive tourist use of the dune lakes on Fraser Island could deleteriously affect their ecology and in turn, their aesthetic appeal to tourists. The findings from this research study suggest that the current level of tourist pressure on the perched dune lakes on Fraser Island is likely to have a significant long-term impact on the ecological health of these systems.>> [>Read Report 830kb, PDF]

.

[c] Read related articles on this website by The Habitat Advocate: >Fraser Island Hoon Tourism out of control

.

Tourist Dingo Branding of Fraser Island

Tourist Dingo Branding of Fraser Island

.

National Parks ‘Tourism Playground’ imperative

.

This ‘Godzilla’ bus especially caters for Bevans to Fraser Island

This ‘Godzilla’ bus especially caters for Bevans to Fraser Island

.

Day-to-day management and protection of the World Heritage property is carried out by the Queensland Government’s Department of National Parks, Recreation, Sport and Racing’s – Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS). Much of their focus and activities is with accommodating the interests of tourists, not with respecting the viability, health of the Island’s important ecosystems, fauna and flora.

The Queensland Government has a revolving record of failed conservation management plans and strategies, reviewed and replaced since the Fraser Island Management Plan of 1975. This includes revisions in 1978, 1986, 1991, 2001, and 2006. The current strategy dated 2001 is termed the Fraser Island Dingo Management Strategy (FIDMS).

Read: >Fraser Island Dingo Management Strategy (2001) (PDF, 270kb)

The overall objectives of the Dingo Management Strategy are to:

- Ensure the conservation of a sustainable wild dingo population on Fraser Island (Ed: numbers not specified, Dingo recovery programme non-existent)

- Reduce the risk to humans (Ed: kill native Dingoes if deemed ‘aggressive’ or ‘showing no fear of humans’)

- Provide visitors with safe opportunities to view dingoes in environment in near as possible to their natural state (Ed: exploit native Dingoes and their habitat for the benefit of wildlife-based tourism revenue)

.

The current Dingo Management Strategy includes a deliberate Dingo persecution set of directives:

Strategy 4: Programs will be implemented to modify dingo behaviour and habits which threaten human safety and wellbeing.

Strategy 5: Any dingo identified as dangerous will be destroyed humanely using accepted methods after receiving appropriate approvals.

Strategy 6: A cull to a sustainable level may be undertaken if research can show the population is not in balance.

A pure Dingo’s cruel fate

A pure Dingo’s cruel fate

.

.

“What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night. It is the breath of a buffalo in the winter time. It is the little shadow which runs across the grass and loses itself in the Sunset.”

.

Implementation of the current Dingo Management Strategy prescribes “direct management of dingoes (destruction of individuals or prescribed culling)…implemented if supported

by the results of research and/or in situations where risks to human life or safety are unacceptably high and cannot be diminished through alternative measures.

Responsibilities of the dingo management Rangers include:

- Public contact to inform Island visitors of appropriate behaviour concerning dingoes

- Enforcement of dingo-related regulations

- Monitoring and recording the status of dingo packs in their management unit (photographic records)

- Marking and tagging pups and problem animals

- Involvement in aversive conditioning projects

- Maintaining dingo-related equipment (traps, fences, dingo incident sheets)

- When authorised, the trapping and destruction of problem dingoes

.

Andrew Powell MP, purely for the Media

Andrew Powell MP, purely for the MediaQueensland Government’s current Minister for Environment and Heritage Protection

.

“People…especially people in positions of power…have invested a tremendous amount of effort and time to get to where they are. They really don’t want to hear that we’re on the wrong path, that we’ve got to shift gears and start thinking differently.”

~ David Suzuki

.

‘Island Playground’ dictates Dingo Culling

.

2009: ‘Residents protest Fraser Island dingo cull’

.

<<Hervey Bay residents met last night and called for an end to the hazing and culling of dingos on Fraser Island. Submissions to the review of the State Government’s dingo management strategy closes next week. Seven dingos have been killed this year compared to three last year. The Opposition’s climate change and sustainability spokesman Glen Elmes says the Government needs to listen to the community.

“We have a situation where the current system and the planning that’s put place to deal with dingos on Fraser Island is all wrong – that’s not me swanning in for half an hour and making that statement. We had a meeting in Hervey Bay last night and we listened to about 30 locals, who represented not only the indigenous community but concerned locals from both the mainland and the island.”>>

[Source: ‘Residents protest Fraser Island dingo cull’, 20090528, by Katherine Spackman, ABC, ^http://www.abc.net.au/news/2009-05-28/residents-protest-fraser-island-dingo-cull/1697234].

2012: ‘Dingo eludes Fraser Island rangers’

.

<<Rangers on Fraser Island have destroyed another dingo at Cathedral Beach, but the K’Gari camp dog ‘Inky‘ still eludes them.

QPWS has decided to bring in a hired gun, a trapper, to destroy this animal. Is this the future of Fraser Island? Residents and visitors are encouraged to throw sticks, shout and kick sand at the animals and to ‘dob in a dingo‘. Some residents have even been advised to shoot them with a slingshot. There is no responsibility placed upon parents who leave children unsupervised or visitors who harass the animals, no fines or penalties, but the dingo pays the ultimate penalty and is destroyed.

The Regional Manager, Ross Belcher, admits the camp dog did not bite anyone, nor did the animal that was recently destroyed, but it has a destruction order because of a complaint by tourists who are considered unreliable and have no understanding of dingo behaviour.

This dingo has been wounded, has a mangled ear due to an infected ear tag and as a result is very wary. Therefore it would seem QPWS has achieved its aim of making the animal fearful of people, why then do they continue their campaign of search and destroy?

Locals lament a time when the dingoes could roam free and occasionally steal a fish or grab a towel from an unsuspecting tourist, it was all part of the Fraser Island experience, but now that animal would be considered dangerous and destroyed.

Unless the Management Strategy review finds in favour of the dingo and not the tourist dollar, the persecution and harassment will continue until there are no longer any animals remaining, this is the legacy of Fraser Island.>>

[Source: ‘Dingo eludes Fraser Island rangers..’, October 2012, by Cheryl Bryant, Save Fraser Island Dingoes Inc., ].

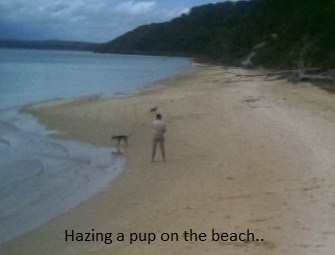

Queensland Government Rangers ‘hazing‘ a Dingo pup in its native Fraser Island habitat

Queensland Government Rangers ‘hazing‘ a Dingo pup in its native Fraser Island habitat

.

‘Hazing’?

.

<<Hazing is harassment, where you disturb the animal’s sense of security to such an extent that it decides to move on.

To be effective, harassment must be continuous, concentrated, and caustic, just like torture.

Always remember that you are trying to convince an animal to leave its home or food source. In short, you must become the animal’s worst neighbor. You must convince the animal that you are more bothersome than the possibility of starvation or homelessness.

.

I. Continuous Harassment

You must harass the animal on a daily basis for as long as necessary. Don’t be surprised if this activity goes on for weeks.

.

II. Concentrated Harassment

Your efforts must focus on the animal causing the problem. For example if you are using noise it must be centered at where the animal is living. Failure to concentrate the harassment technique simply makes the animal get used to the problem because the problem will be everywhere. It’s like living in N.Y. City. You get used to the traffic noise.

.

III. Caustic Harassment

The harassment technique must be bothersome to the animal. The greater the discomfort to the animal the faster the technique will develop results. Warning: when you harass an animal there are no guarantees where it will decide to take up residence next. It is not out of the question that a raccoon, upon leaving your chimney will decide to enter your attic.>>

.

[Source: Internet Centre for Wildlife Damage Management, America, ^http://icwdm.org/ControlMethods/Hazing.aspx].

Bevans in typical distress on Fraser Island

Bevans in typical distress on Fraser Island

.

.

Related Articles (this website)

.

[1] >Dingo Ecology deserves respect on Fraser Is

.

[2] >Remove all ferals from Fraser Island

.

[3] >Dingo: Australia’s ancient apex predator at risk

.

[4] >Fraser Island Hoon Tourism out of control

.

Queensland Tourism Legacy

Queensland Tourism Legacy.

.

Further Reading

.

[1] Save Fraser Island Dingoes Inc., President: Malcom Kilpatrick. President, Website: ^http://savefraserislanddingoes.com/

.

[2] Australian Wildlife Protection Council, President: Maryland Wilson, ^http://www.awpc.org.au

.

[3] ‘Fraser Island Dingo Management Strategy‘, November 2001, Environmental Protection Agency – Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS), Queensland Government, ^http://www.nprsr.qld.gov.au/register/p00500aa.pdf [>Read Strategy]

.

[4] ‘Review of The Fraser Island Dingo Management Strategy – Terms of Reference‘, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection,

^http://www.ehp.qld.gov.au/wildlife/livingwith/dingoes/pdf/fidms-review-tof.pdf [>Read Strategy]

.

[5] ‘Fraser Island Dingo Management Strategy – Review‘, December 2006, ^http://www.nprsr.qld.gov.au/register/p02215aa.pdf [>Read Report]

.

[6] ‘Stakeholder Workshop‘ . A vague title, but yet another…Fraser Island Dingo Management Strategy Review, this time by Ecosure (consultancy outsourced by Queensland Government), 20121005, ^http://www.ecosure.com.au/business-units/wildlife-management/alias/fidms/, http://www.ecosure.com.au/uploads/documents/ibis/Stakeholder%20workshop%20-%20summary.pdf [>Read Summary]

.

[7] ‘A History of Fraser Island‘, 2011, by Pat O’Brien, President, Wildlife Protection Association of Australia Inc., ^http://www.awpc.org.au/img/A_History_of_Fraser_Island_2011_by_Pat_O__Brien..pdf [>Read Paper]

.

[8] Wildlife Protection Association of Australia Inc. (WPAA), PO Box 309, Beerwah, Queensland Australia, 4519, President: Pat O’Brien, ^http://www.wildlifeprotectaust.org.au/

.

[9] Coalition for Wildlife Corridors, Kindness House, 2nd Floor, 288 Brunswick St, Fitzroy 3065, Victoria, Australia, (no website found)

.

[10] ‘ If they could talk to the animals…‘, book by Jonathan Knight, in Nature, Vol.414, pp.246-247, (no website found)

.

[11] ‘Vanishing Icon, the Fraser Island Dingo‘, by Jennifer Parkhurst, 2010, Grey Thrush Publishing, ^http://www.fraserislandfootprints.com/?page_id=694,

Main Website: ^http://www.fraserislandfootprints.com/

[12] ‘Dingo‘, by Brad Purcell, 2010, CSIRO Publishing, ^http://www.publish.csiro.au/pid/6430.htm

Abstract:

<<Many present-day Australians see the dingo as a threat and a pest to human production systems. An alternative viewpoint, which is more in tune with Indigenous culture, allows others to see the dingo as a means to improve human civilisation. The dingo has thus become trapped between the status of pest animal and totemic creature. This book helps readers to recognise this dichotomy, as a deeper understanding of dingo behaviour is now possible through new technologies which have made it easier to monitor their daily lives.

Recent research on genetic structure has indicated that dingo ‘purity’ may be a human construct and the genetic relatedness of wild dingo packs has been analysed for the first time. GPS telemetry and passive camera traps are new technologies that provide unique ways to monitor movements of dingoes, and analyses of their diet indicate that dietary shifts occur during the different biological seasons of dingoes, showing that they have a functional role in Australian landscapes.

Dingo brings together more than 50 years of observations to provide a comprehensive portrayal of the life of a dingo. Throughout this book dingoes are compared with other hypercarnivores, such as wolves and African wild dogs, highlighting the similarities between dingoes and other large canid species around the world.>>

[13] ‘Butchulla people – Traditional Owners of K’gari (Fraser Island)‘, by Dale Lorna Jacobsen, ^ http://dalelornajacobsen.com/5_butchulla_website; Also: ^http://dalelornajacobsen.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Butchulla_pathways.24174426.pdf, [>Read Brochure, PDF, 2.8MB (large file, so may take a while to download)]

.

[14] ‘Finding Fraser Island‘ by Ken Eastwood, in Australian Geographic, Vol.107, March – April 2012, pp. 67-79.

.

[15] ‘Fraser Island World Heritage Area‘, Department of National Parks, Recreation, Sport and Racing, Queensland Government, ^http://www.nprsr.qld.gov.au/world-heritage-areas/fraser_island.html

.

[16] ‘When Wildlife Tourism Goes Wrong: A Case Study of Stakeholder Management Issues Regarding Dingoes on Fraser Island, Australia‘, May 2006, by Georgette Leah Burns and Peter Howard, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia, ^http://www98.griffith.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/handle/10072/6029/When_wildlife…?sequence=1, [>Read Paper, PDF, 175kb]

.

[17] A Draft Dingo Management Strategy for Fraser Island, by the Fraser Island Defenders Organisation (FIDO), ^http://www.fido.org.au/DingoManagement.html

See reproduced as follows..

.

An Ecologically Respectful Custodial Strategy for Fraser Island (by FIDO).

.

<<For more than 28 years, the Fraser Island Defenders Organization has been researching the management of Fraser Island to be in the best position to advocate the wisest use of its natural resources. The organization has a longer history associated with the management than any other organization, including the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service and its predecessors.

The Fraser Island Defenders Organization has studied and considered the Draft Fraser Island dingo management strategy prepared by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service and this submission is a response to that document released in April, 1999.

This organization has examined Draft Dingo Management Strategy and recommends some very important issues which need to be recognized and also some significant changes which need to be made to the actions.

.

1. FIDO wants the genetic status of Fraser Island dingoes recognized and protected.

2. Dingoes should be allowed to remain free to roam in the wild on Fraser Island.

3. The strategy should address all of the issues relating to the dingo population, including the characteristics, and the changes during the past century.

4. There is a need to review the population dynamics of Fraser Island dingoes to ensure that the island environment is managed to achieve an optimum dingo population. This needs to recognize that historically there was a much higher population on Fraser Island.

5. Dingoes should not suffer because of the intervention of humans which have induced changed behaviour.

6. A humane system of tagging should be established and all Fraser Island dingoes should be individually identified to provide more precise data on the actual population numbers and to assist in further research on animal behaviour.

7. The strategy should recognize how environmental changes during the last century on Fraser Island have impacted on dingoes and move to minimize these impacts.

8. The QPWS should develop a code of conduct which not only outlaws feeding of dingoes but also one which stops people encouraging dingoes to approach closer than 10 metres to be photographed thus encouraging them to loose their wariness of humans.

9. FIDO generally supports the first four recommendations of the Draft Dingo Management Strategy but is opposed to the recommendations for relocation, destruction, and culling.

.

1. Significant Omissions

There are a number of significant omission in the Draft Fraser Island dingo management strategy. The most important omission seems to be a clear objective for the strategy. Other omissions relate to the history of the dingo on Fraser Island, the significance and genetic purity of the dingoes on Fraser Island, the status of dingoes and the impact of environmental changes during the last 100 years.

1.1 The need for a clear objective: The Strategy should clearly state its objective. Without such an objective being clearly and publicly stated implementations of the final three recommendations could result in the extermination of the dingoes on Fraser Island. Is it to protect people from harassment by dingoes or is it to protect the animals? Is it to be an outcome that the genetic strain of Fraser Island dingo is only to be preserved in a zoo or behind barriers or is it to ensure that dingoes are to be allowed to roam wild on Fraser Island?

At present the objective could be construed only as stopping dingoes attacking humans.

The Fraser Island Defenders Organization believes the Final Management Strategy should carry wording such as:

“The biologically importance of the Fraser Island dingo strain is a value which must be preserved in as pure a form as possible. The fact that dingoes have lived on Fraser Island in the wild for thousands of years makes it important that the dingoes are allowed to roam as wild and unconfined animals on Fraser Island.

“The object of this strategy is predicated by the need to ensure that a viable wild population of dingos is maintained on Fraser Island.”

1.2.1 History: The bibliography of the Draft Fraser Island Dingo Management Strategy fails to include any reference to any material relating to dingoes prior to 1994. The Draft Strategy doesn’t refer to any material from early in the Century which would give the current situation a different perspective. FIDO believes that this is a significant omission because it fails to give a proper perspective to the current dingo management problems on Fraser Island.

In 1976, FIDO began formally collecting and recording oral history from veterans whose memory of Fraser Island extended back as far as 1905 (Jules Tardent). This collection of historical perspectives has continued since. In all of FIDO’s questioning, there was never any mention of dingoes attacking humans. There were also many reports that dingoes were afraid of humans.

1.2.2 Past Populations: All accounts appear to support the claims that the dingo population on Fraser Island in the early part of the 20th Century was much higher. This needs to be compared with the current estimated “population of 25 to 30 packs peaks at approximately 200 animals during whelping in June-July” which is stated in the draft strategy.

1.2.3 Past population estimates: While all estimates are very subjective were likely to have greatly exceeded 1,000. In personal conversations Rollo Petrie puts the population around 1915 to 1922 as possibly up to 2,000. In “Early Days on Fraser Island — 1913-1922″, he provides a theory of why he believed that the dingo numbers built up rapidly when they no longer had to compete with the Aboriginal population of 2,000 to 3,000 for food.

Petrie refers to comparative number (pp 59-60). He refers to numbers: “(Available food) would not be as plentiful now if there was an equivalent number of dogs on Fraser Island, as in the early 1900’s. The few dingoes now live comfortably on scraps …” Further on he reports: “George Jackson on a trip to Indian Head, found a freshly shot stallion on the beach a few miles south of Indian Head. George … poisoned the carcass and then camped not far away. Next morning he had 100 scalps and not a great deal of the horse was left.”

1.2.4 Relevance of historical dingo population: The significance of the size of Fraser Island’s dingo population in the past is important because it reflects on the carrying capacity in the past. It would seem to indicate that environmental changes are responsible for a diminution of the island’s carrying capacity for dingoes.

Other aspects of dingo numbers are important because most geneticists would regard a population of 100 on an island, isolated from other genetic sources as a very risky. This will be discussed further below as that has major implications for management.

1.3.1 Significance of Fraser Island Dingoes: The significance of the genetic purity and the importance of the Fraser Island Dingo population is significantly understated in the Draft Strategy. The Draft (Para 2) only states, “Fraser Island dingoes … are likely to be the purest strain of dingoes on the eastern Australia seaboard.” Nowhere else does the strategy even refer to the fact that such an important gene pool needs to be protected and perpetuated.

It is FIDO’s submissions that the genetic significance of the Fraser Island dingo strain justifies all efforts to protect and preserve this gene pool.

1.3.2 Preserving the Gene Pool: Assuming that the population peak of 200 is accurate, this is a very small gene pool on which to base a program for further reducing that gene pool. It is more worrying in the context that on anecdotal evidence the population has significantly declined over the past 8 decades.

If the numbers drop below “100 animals when breeding recommences”, as the draft strategy states, then the viability of the gene pool is at risk.

The significance of this special genetic purity of the Fraser Island dingo seems to have been overlooked in the final 3 actions recommended in the draft management strategy which refer to relocation destroying and culling. FIDO is therefore strongly opposed to these three actions.

.

2. Keeping dingoes in the wild

2.1 Keeping Dingoes in the Wild: There is little acknowledgment that dingoes have a right to remain on Fraser Island in the wild. This is an a very important principle. It is not stated in any objective.

Dingoes have roamed free on Fraser Island probably since they first appeared in Australia which is at least thousands of years. Therefore, dingoes have a right to continue to roam freely over the island within the constraints of any wild animal which has learnt to be wary of other predators such as humans in their natural environment.

2.2 Saving a wild population in the wild: This organization does not want to see the Fraser Island dingo gene pool preserved only in wildlife parks or zoos or in special enclosures on Fraser Island. The establishment of large dingo free areas while it could be administratively convenient would be unacceptable. However, having said that this organization believes that it is important to try to ensure that dingoes do not become dependent on humans. Therefore they should be discouraged from areas where there is likely to be unnatural close interactions with humans. FIDO therefore would like to see more attempt made to deter dingoes from frequenting the settlements and camping areas such as Central Station and Lake McKenzie.

FIDO is vigourously opposed to any form of enclosure and artificial feeding programs. This is only encouraging a naturalized animals to behave unnaturally. Furthermore the Thylacines became extinct because they were hunters and would not accept being fed in a zoo. While dingoes are opportunistic feeders and will accept any handouts, it is still unnatural to hand feed them.

The loss of dingoes in the wild on Fraser Island would represent a much greater tragedy than the loss of the European wolves, because whereas wolves threatened humans in their domestic circumstances, Fraser Island dingoes only represent threats to humans in their recreation. We see the need to recognize and state these principles categorically in the final form of the management strategy.

Recommendation: In view of the above FIDO urges that a new section be written into the Strategy which addresses all of the issues relating to dingo population, the characteristics, the changes during the past century, and the need to maintain a viable population in the wild.

3. Population

We need a much better idea of the Fraser Island dingo population. We need to know the dynamics of reproduction and replacement rates, distribution of the population, the degree of interbreeding and an understanding of the reasons for any changes.

3.1 Accurate data needed: Because of the apparently critical size of the gene pool, there is an urgent need to have more precise information about the current population both in a macro and a micro sense.

More detailed work is needed to accurately determine:

(a) the current population in total,

(b) the distribution,

(c) the annual loss deaths of marked animals,

(d) the recruitment of new animals to the population on an annual basis and

(e) the identity of individual animals to that their behaviour can be observed.

.

3.2 Tagging: We believe that it is necessary to have a more precise estimate of numbers on Fraser Island even if this may mean tagging of every individual. This would then enable a better understanding of the numbers and the distribution and assist in identifying individuals.

The process of tagging also has other potential implications for dingo management which are discussed below. Depending on how it is done it could help reinstate a greater caution of humans and encourage them to keep their distance. This organization is aware that the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service tagged every crocodile in the East Alligator River as part of its program to better manage the largest single population of estuarine crocodiles in the world. If it was possible to tag every crocodile in this part of Kakadu 20 years ago, it should be possible to tag the estimated 100 dingoes on Fraser Island before whelping. The results of that tagging which was done almost 20 years ago continues to yield valuable research results in helping understand the behaviour of those animals. We believe that crocodiles are a more dangerous and difficult animal to catch and tag than dingoes and therefore this should be a priority task to any ongoing research program.

Recommendation: A humane system of tagging should be established. All dingoes on Fraser Island should be tagged to enable them to be readily identified. The objective of tagging would be also to provide more precise data on the actual population numbers and to assist in further research on animal behaviour.

.

4. Environmental Changes

The Draft dingo management strategy makes no reference to the environmental changes which have occurred on Fraser Island during the last century. A reference to old photographs and Petrie’s Fraser Island memoirs will show that there have been very significant environmental changes to the whole island during the past 80 years. Petrie’s observations are confirmed by all people who knew Fraser Island before the 1930s. These observations are also borne out by photographic evidence.

It is FIDO’s belief that these environmental changes have very significantly impacted on the dingo food sources.

4.1 Understorey changes: In “Early Days on Fraser Island 1913-1922”, Petrie described a number of changes. He described the lack of understorey on the island. Evidence of this is demonstrated by the number of horses which the island accommodated. Petrie estimated numbers as high as 2000.

With the change in the fire regime the understorey has caused not only the loss of grass but also the loss of a number of small mammals such as bandicoots. For example, “Bandicoots were fairly plentiful in the 1915 to 1920s in the Wanggoolba area,” Petrie said.

4.2 Changes to the traditional Fire Regime: FIDO attributes the loss of habitat of small mammals, which would have been traditional dingo food, to the changes away from the traditional Aboriginal burning regime. There is strong evidence to link the growth of the dense woody understorey, and in turn the reduction in small mammal population, (and in turn the decline of Fraser Island’s dingo population) with the absence of fire particularly in the tall forest where fire was deliberately excluded for more than a century.

Recommendation: FIDO believes that Fire Management Plan for Fraser Island to return the island to a habitat which is more suitable for small mammals and in turn for dingoes should be developed and implemented as a matter of the highest priority

4.3 Tradition hunting on beaches: Petrie also said that then dingoes used to eat wongs (eugaries) from the beach and fractured shells were regularly found in dingo droppings. It is apparent the use of the beach by so much beach traffic has denied this source of food to dingoes and / or they have lost this traditional hunting skill.

FIDO believes that some more research should be undertaken to identify ways which would encourage dingoes back to this traditional food sources such as wongs from the beach.

.

5. Modifying the Animal Behaviour

The major problem seems to result from the changed behaviour of animals to humans. FIDO contends that to a large extent this changed behaviour is human induced. In this section, FIDO focusses on what needs to be done to modify animal behaviour.

5.1 Domestic Animals Attacked: Petrie and others referred to the fact that domestic animals were vulnerable to dingo attacks. “I have seen working bullocks bogged in the peat swamps. … The dingoes started eating them from the rear.” (p59) and “… my horse Moses was freshly bogged and already dingoes were circling around him…” (p 60) The writer has recorded oral history of dingos cornering brumbies in the surf. There are many stories of dingoes attacking and eating domestic dogs in the 1970s until domestic dogs were banned from Fraser Island. However, despite the predatory behaviour of dingoes towards other mammals, there are no records or reports of dingoes representing threats to humans on Fraser Island.

5.2 Loss of Fear of Humans: FIDO attributes the recent behaviour of dingoes to the fact that dingoes have lost their fear or wariness of humans. That the change dingo attitude is apparent from this recorded Petrie anecdote: “Recently when I camped out on the island, I heard something close by. I sat up in my swag. In the moonlight, I saw two dingoes about 15 feet away. I picked up a bit of wood and tossed it towards them. The dogs trotted to the stick and smelt it. It was a far cry from the days when they would have fled at my first move.” (p 60) Similar stories were reported by other early visitors to Fraser Island.

5.3 Problem Not Confined to Fraser Island: This behaviour change has only happened in the last fifteen years but the boldness of the dingoes continues to grow manifesting itself into an increasingly serious problem. The problem is coincidental with changes to dingo behaviour in other Australian National Parks with significant dingo populations. This was demonstrated by the Azaria Chamberlain case at Uluru. However, similar patterns are now being observed at Kakadu and in Jabiru township where dingoes refuse to be chased away as the writer observed as recently as February, 1999.

5.4 Feeding is Not the Only Problem: The Draft Management Strategy makes a case for feeding dingoes as the main reason that dingoes have lost their fear. FIDO has reason to believe that it is not only feeding which has transformed dingo behaviour. Dingoes have been fed by humans on Fraser Island for at least 50 years in the writers experience. Ignoring the past history is to overlook the underlying cause for this quite dramatic change in behaviour from one of wariness of humans to one of boldness.

5.5 Tagging to aid research: As mentioned above, if there are only 100 animals now left on Fraser Island, then tagging every animal is not an insurmountable problem and it will greatly assist identifying rogue animals and in studying animal behaviour. It should be noted that on Maria Island where detailed studies are made of the Tasmanian native hens, every animal in the vicinity of Darlington is tagged and these tags are observed to identify individuals when studying behaviour. The whole estuarine crocodile population in the east Alligator River section of Kakadu National Park was also caught and tagged.

5.6 Tagging to Discourage Approaching Humans: Normally animals who are trapped are very wary of approaching humans again. This is particularly true of cats, foxes and dingoes. However, some animals welcome the gentle treatment after trapping and back up again and again to be caught. The trapping must be done humanely but in ways which dramatically increases the wariness of approaching humans. Each animal should be trapped and tagged in ways which subsequently discourage them from approaching too close to humans.

5.7 Destroying Rogues: As indicated above, this organization is opposed to the destruction of rogues. We are more alarmed because by our estimates more than 30 animals have been destroyed over recent years. This great loss to the population has not diminished the occurrence of dingo attacks on humans.

While destruction of rogues is a recognized short term solution such methodology should have been carrying out with more foresight. For example if others in the pack saw a rogue approaching a human or the human approaching the rogues and then seeing the rogue die, this would be soon communicated widely amongst dingos. Instead, in some cases such as following a Happy Valley attack, whole packs were eliminated.

Nothing was gained from this slaughter other than creating a territory soon taken up by other animals which were not witness to the killing of their reasons. Thus, FIDO can’t support such a counter-productive spontaneous reaction.

5.8 Identifying Humans with Unpleasant Outcomes: It is important that when reprisals do occur all animals are able to identify humans with the unwelcome outcome. This will help to reinstate the wariness of humans.

While aversion baits might be important to discourage scavenging for food scraps, this program is unlikely to ensure that dingoes to keep their distance from humans or even attacking them. However, we accept that aversion baiting may reduce scavenging.

5.9 Use of repellents: This organization supports more research to find and develop more effective dingo ultrasonic deterrents. If this is successful they should be used at all significant places where humans congregate such as Lake McKenzie, Central Station and the urban centres to try to keep dingoes out of these places.

.

6. Changing Human Behaviour

The Dingo-Human interaction part of the Strategy should identify the two distinct aspects of the problem. Just as important as causing dingo behaviour to revert to its previous pattern, the public must be better educated by both carrot and stick to recognize that every human has a responsibility to ensure that dingoes keep their distance.

6.1 Camera enticements: FIDO considers that the most overlooked factor has been the fact that dingoes have been increasingly enticed to come closer and pose for the cameras. This enticing of dingoes to approach humans without fear is quite deliberately saying to the animals that they have nothing to fear from humans. FIDO believes that this is even more subtle than feeding the animals as a form of changing animal behaviour and it should be stopped. The change in dingo behaviour to humans seems to occur only on national park and areas where there is no threats to the animals. The increase in the frequency of photography of the animals seems to have contributed significantly.

Recommendation: The QPWS should develop a code of conduct which not only outlaws feeding of dingoes but also one which stops people encouraging dingoes to approach closer than 10 metres to be photographed. This should be enforced with vigour.

6.2 The Blind Eye: It is true that feeding has been a factor but it is also true that a blind eye has been frequently turned towards the feeding of dingoes. On every occasion the author has spent more than 5 days he has observed someone feeding dingoes.

FIDO therefore support the recommendation in the Draft Dingo Management Strategy that feeding will be prohibitted. We just hope it will be pursued with more determination than we have observed in the past.

6.3 More active Interest from the QPWS: This organization also believes that more concern needs to be taken of the reports of dingo attacks on humans. In 1996, the writer’s sister who has been visiting Fraser Island for more than 30 years was subject to an unprovoked attack by an animal on the beach as she was walking alone near the surf edge. She reported it to the Eurong Visitor’s Centre to a completely disinterested staff and she is not even sure that any record was made of her report.

.

7. Destruction, Culling and Relocation

This Organization supports the first four recommendations of the Draft Dingo Management Strategy in principle with some modifications and revision in the light of the above submissions. We particularly believe that more research is warranted to understand the behaviour patterns of particular animals.

FIDO though is opposed to the last three recommendation options in the Draft Fraser Island dingo management strategy, relocation, destruction, and culling. These have all been used regularly over the last five years without any significant benefit in improved dingo behaviour. In fact the dingo behaviour has if anything changed to the dingoes becoming even bolder. While such measures may assuage the injured feelings of the public immediately after any attack by dingoes on humans, it has been demonstrated over the years that they provide no long term improvement in animal behaviour.

Therefore on practical as well as humane grounds, FIDO is opposed to these measures. However, more significantly, in view of the size of the dingo gene pool on Fraser Island of just 100 breeding animals, we do not believe that these measures can be justified on conservation grounds. The preservation of genetic diversity must be one of the foremost objectives of the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. Thus we are opposed to further reducing the gene pool of Fraser Island’s pure dingoes.

The Fraser Island dingo should not become like the European bears, wolves, and an number of other wild creatures which culled to the point of extinction outside zoos and a few isolated populations because they competed with human populations.>>