Posts Tagged ‘Blue Gum Forest’

Wednesday, January 22nd, 2020

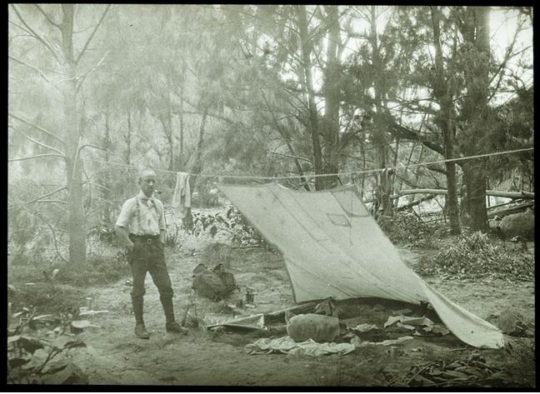

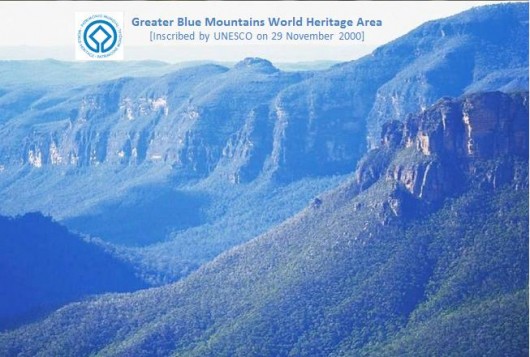

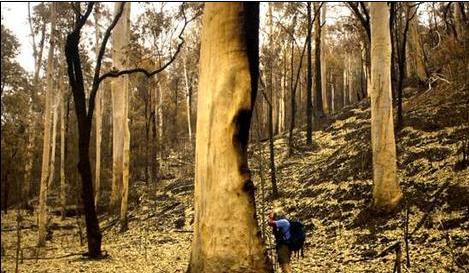

Pre-2006: The Grose Valley’s 500m+ deep upper Grose Gorge displayed a Blue Mountains profile of sandstone cliffs above talus thickly carpeted by Eucalypt forest supporting rich diversity in plantlife, wildlife, birdlife, creeklife and buglife – just an eco-happy cradle of conservation. Pre-2006: The Grose Valley’s 500m+ deep upper Grose Gorge displayed a Blue Mountains profile of sandstone cliffs above talus thickly carpeted by Eucalypt forest supporting rich diversity in plantlife, wildlife, birdlife, creeklife and buglife – just an eco-happy cradle of conservation.

(NB: This photo shows Eucy-mist, not Eucy-smoke. – Ed.)

In 1926, developer Ernest Williamson famously described the Blue Gum Forest in the heart of Grose Valley in the Blue Mountains thus:

“… a flat, unsurpassed on the mountains for the beauty and grandeur of its trees! Magnificent blue gums, straight and towering skyward in great heights … they appear like the huge pillars of a mountain temple.”

Ernest went on to more infamously propose:

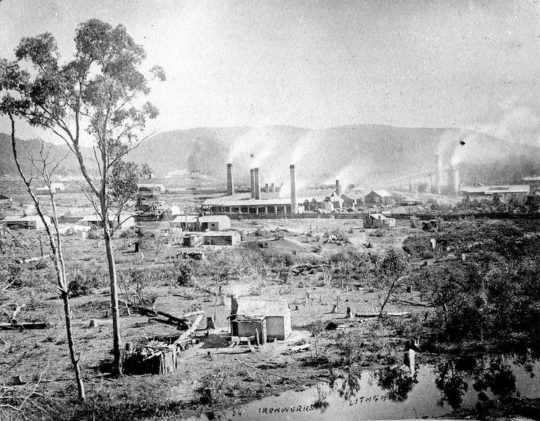

“the Valley of the Grose could, in a few years, be transformed from a riot of scrubland to a hive of industry conveniently situated at what has been aptly described ‘the back door of Sydney’”.

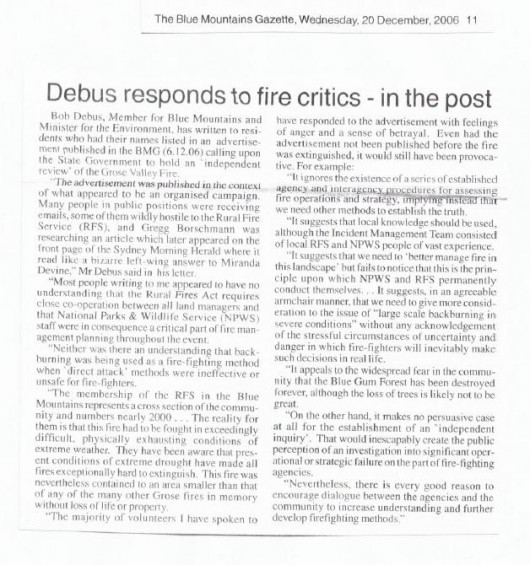

According to Blue Mountains historian and author, Andy Macqueen, Williamson’s property development outfit calling itself The Grose Valley Development Syndicate, proposed in the 1920s or the Grose Valley’s forests to be deforested for timber exploitation and that a shale coal mine and coal-fired power station be built there. It would be an industrialised Lithgow Mark II. Other threats to the Blue Gum Forest included a proposed railway line and a dam. So why not a tannery and nuclear waste dump to boot?

Grose Valley Vision Splendid? – a gross Lithgow industrial vision…note the few remnant token gums retained for ambience, or was it just slack ‘clearing’. Grose Valley Vision Splendid? – a gross Lithgow industrial vision…note the few remnant token gums retained for ambience, or was it just slack ‘clearing’.

Blue Gum Forest – Australia’s Cradle of Conservation

For generations since the 1920s, conservationists have posited somewhat a more respectful plan for the Grose Valley than by Ernest Williamson and his robber-barons. The plan being to respect and conserve the ecological values and the anthropocentric aesthetic ‘eye-candy’ tourist benefits of the Grose Valley.

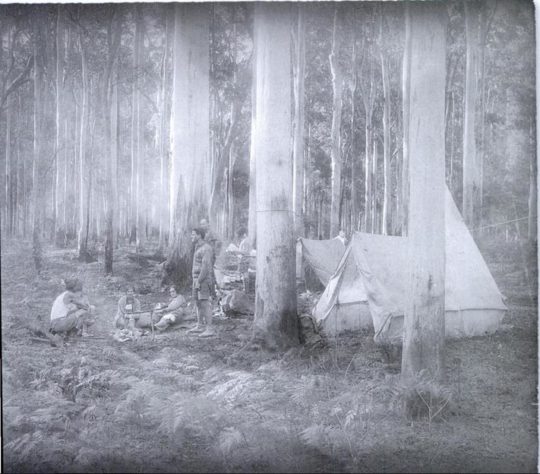

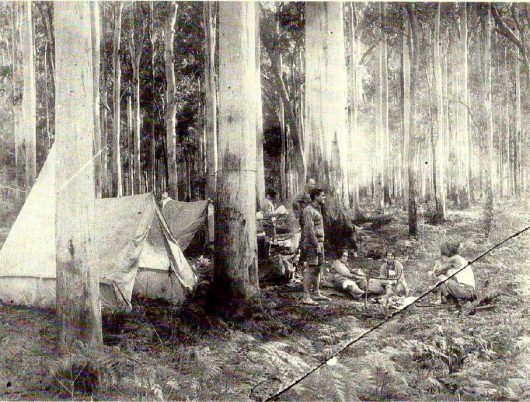

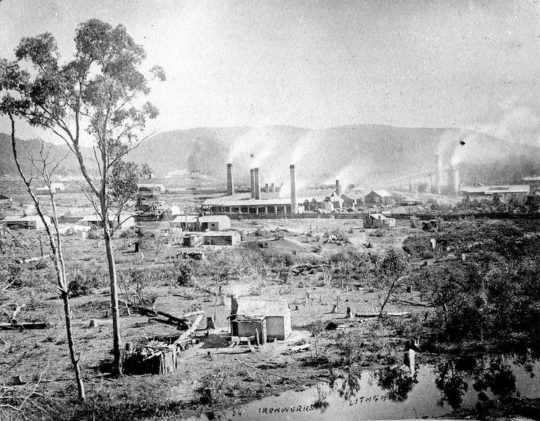

Since 1875, the Blue Gum Forest was the scene of an artists’ camp established by Frederick Eccleston Du Faur of the Academy of Art. Since then, conservationists have lobbied to protect the Grose Valley from “alienation” – read ruination.

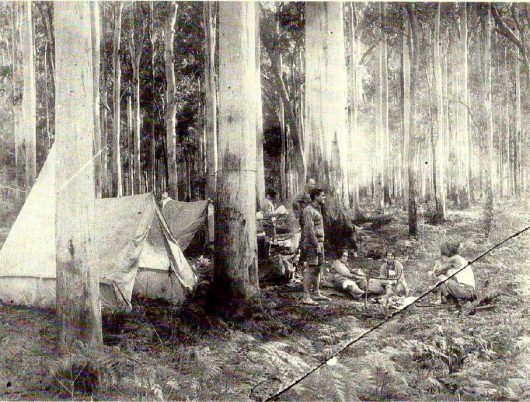

In 1931, during an Easter hiking trip, a group of bushwalkers from the Mountain Trails Club and the Sydney Bush Walkers club, led by Alan Rigby, camped in the Blue Gum Forest.

Since 1931 the Blue Gum Forest has been ecologically recognised and presumed protected. Since 1931 the Blue Gum Forest has been ecologically recognised and presumed protected.

[Source: Myles Dunphy Collection, Mitchell Library in the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.]

While the bushwalkers camped, an orchard farmer of Bilpin, Clarence Hungerford, rode in on his horse to confront the bushwalkers ‘squatting’ on his property. Hungerford had secured a lease of the forest to graze his cattle. Hungerford told to the hikers that he intended to deforest all the blue gums and to sell the timber in order to finance a walnut orchard.

Blue Gum Forest – flagged for deforestation in 1931 for Hungerford’s walnut orchard ‘vision splendid‘ Blue Gum Forest – flagged for deforestation in 1931 for Hungerford’s walnut orchard ‘vision splendid‘

The bushwalkers’ Hungerford experience didn’t go down well. Incensed and horrified, the bushwalkers immediately started a campaign to stop Hungerford’s decimation of the Blue Gum sanctuary. Their impassioned rallying ultimately raised £130; quite a substantial sum in the depth of the Great Depression. They then paid all the funds to Hungerford in exchange for his undertaking to relinquish his pastoral lease of the Blue Gum Forest.

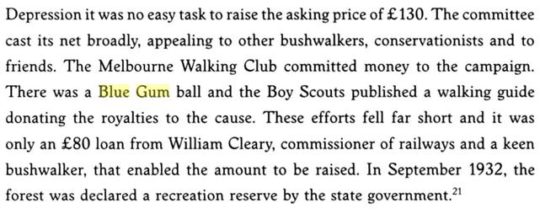

The bushwalkers met with Hungerford at the Blue Gum Forest on 15 November 1931 in pouring rain, and he agreed with their suggestion. Most of the funding had been donated by James Cleary, then head of the NSW railways, a keen bushwalker and conservationist. One of the key activists in the campaign was Myles Dunphy, who at the time was developing his plans for the Blue Mountains National Park.

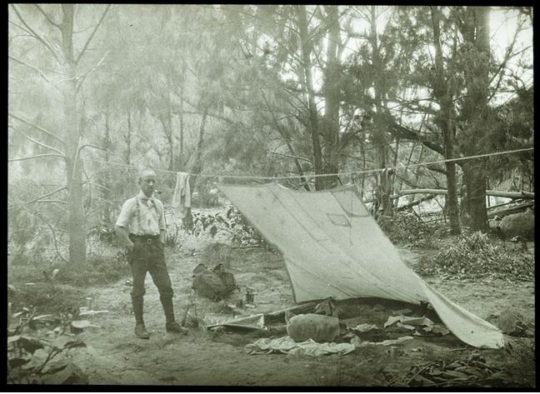

“We hold our land in trust for our successors.” (1934) – Myles Joseph Dunphy (1891-1985), architect, legendary long distance wilderness trekker, map maker, and conservationist before his time. Dunphy always took his Lee Enfield .303 with him for hunting for food when trekking, like on this occasion – it’s under wraps under the tent fly. A daily twilight roo kill for protein was the secret behind him managing to trek his incredible distances. Born on 19 October 1891 in South Melbourne, eldest of seven children… [Read More] “We hold our land in trust for our successors.” (1934) – Myles Joseph Dunphy (1891-1985), architect, legendary long distance wilderness trekker, map maker, and conservationist before his time. Dunphy always took his Lee Enfield .303 with him for hunting for food when trekking, like on this occasion – it’s under wraps under the tent fly. A daily twilight roo kill for protein was the secret behind him managing to trek his incredible distances. Born on 19 October 1891 in South Melbourne, eldest of seven children… [Read More]

Hungerford’s horse track became a developer tribute to Hungerford. The contour-following bush track starts about 300m south of Evans Lookout and descends zig-zagging down the escarpment to the flats of the Grose Valley at Govetts Creek. In its ignorance, the NPWS or more aptly, the Tourist Parks Service, named this track ‘The Horse Walking Track’ – for visitors to walk their horses?

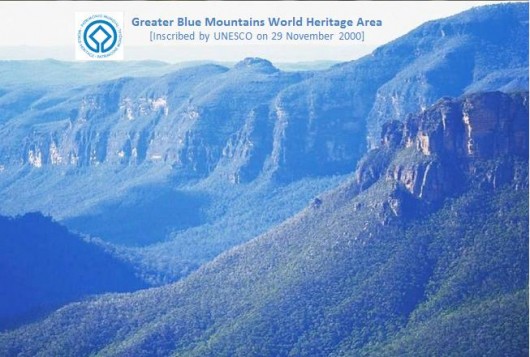

The Blue Gum Forest has since been referred to in the conservation movement as the Cradle of Conservation for it was the focus of Australia’s original ecological protection by a small group of “thoughtful, committed citizens” (Margaret Mead quote extract) and which seeded generations later, the international listing of The Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area in 2000. What legends!

Blue Gum Forest survives only as photos, posters and memories. [Source: ‘Blue Gum Forest 18-19 October 2014‘, 20141022, © by Dave Noble, ^http://www.david-noble.net/blog/?p=6001.] Blue Gum Forest survives only as photos, posters and memories. [Source: ‘Blue Gum Forest 18-19 October 2014‘, 20141022, © by Dave Noble, ^http://www.david-noble.net/blog/?p=6001.]

David Noble is the parks ranger who discovered Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis) in 1994. In September 2012, Noble revisited the Blue Gum Forest leading a hike to celebrate eighty years since the Blue Gum Forest was saved on 2nd September 1932.

Dave wrote at the time:

“This majestic forest lies at the intersection of the Grose River and Govetts Creek near Blackheath. Back in 1932, a large portion of the forest (it was then private land) was going to be felled and replaced by walnut trees. Visiting bushwalkers were alarmed, and rallied together and ended up raising money to purchase the block in question and saving it for conservation. Many regard this as the start of the conservation movement in NSW.”

[Source: ‘Blue Gum Forest – 80th Anniversary 1-2 September 2012‘, 20120913, by Dave Noble, ^http://www.david-noble.net/blog/?p=1846]

But conservationist idealism ignored the arsonist culture. Government baby boomer arsonists have had a view of native Eucalypt forests like the Blue Gum not as cherished ecology but as a valueless hazard, just like Williamson, generations before. The New South Wales Government ‘autorities’ have been chafing at the bit for years to hazard reduce Blue Mountains World Heritage “fuel“.

History of Neglectful Arson

In December 1957, a bushfire that was left to burn in bushland east of the Grose Valley, once the wind picked up, ultimately ripped through the timber clad villages of Leura and Wentworth Falls destroying 170 homes.

In December 1976, 65,000 hectares of Blue Mountains native bushland was burnt. A year later, a bushfire burnt out 49 buildings and another 54,000 hectares of Blue Mountains native bushland.

In summer 1982 a bushfire burnt right through the Grose Valley incinerating 35,000 hectares of tall native forest, and wildlife.

Again in 1994 the Grose Valley was let burnt by bushfire.

Grose Valley Arson in November 2006

Again in November 2006 the RFS backburned into the Grose Valley from Hartley Vale. Ignited by Rural Fire Service along the north side of Hartley Vale Road on a day of Total Fire Ban, bush arson incinerated native forest ecology up the length of Hartley Valley Road and then was allowed to spot over the Darling Causeway let descend into the Grose Valley. It was deliberate bush arson sanctioned by the NSW Government under then RFS Commissioner Mal Cronstedt at the time.

The fire was fanned by westerly winds over days, allowed to cross over the Darling Causeway, merge with the Burra Korain wildfire and descend down Perrys Lookdown hiking track in and through the Blue Gum Forest. Many Blue Mountains residents will be well familiar with this infamous photo of the Grose Pyrocumulus (flammagenitus) cloud rising from the Grose Valley on Thursday afternoon 23rd November 2006.

Grose Valley incineration of 2006. [Source: ‘2006 Grose Fires – the realisation of a tragedy, 20070707, The Habitat Advocate, >https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/2006-grose-fires-the-realisation-of-a-tragedy/] Grose Valley incineration of 2006. [Source: ‘2006 Grose Fires – the realisation of a tragedy, 20070707, The Habitat Advocate, >https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/2006-grose-fires-the-realisation-of-a-tragedy/]

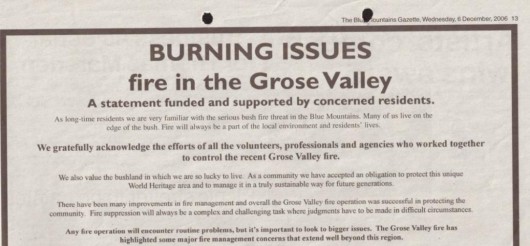

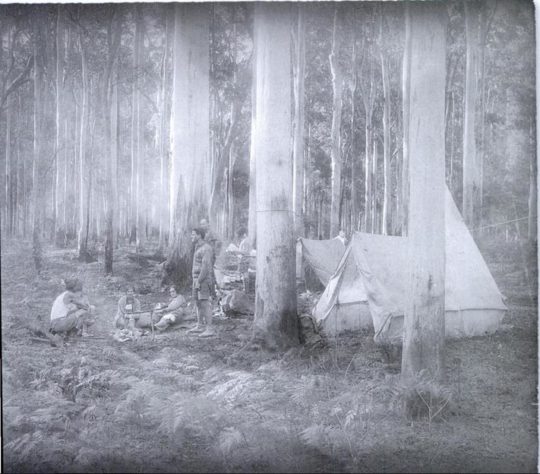

At the time there was local community outrage about how the precious Blue Gum Forest was not defended by authorities and allowed to be incinerated. Blue Mountains resident meetings were staged and a full page article was published in the Blue Mountains Gazette newspaper entitled >’Burning Issues – Fire in the Grose Valley (a statement funded and supported by concerned residents‘. It would have cost at least $2000. Community meetings were held, arranged by former parks ranger Ian Brown. But then it got political and the campaign was strangely suddenly aborted.

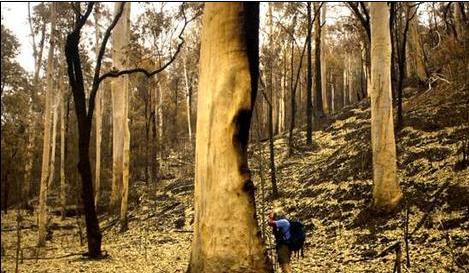

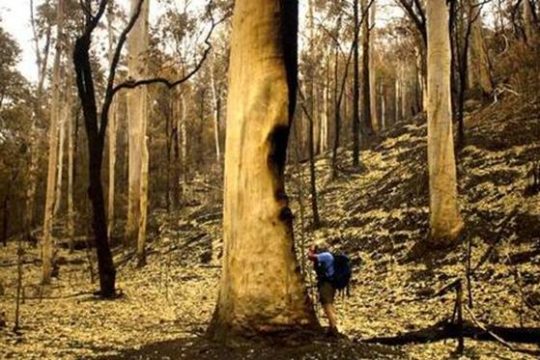

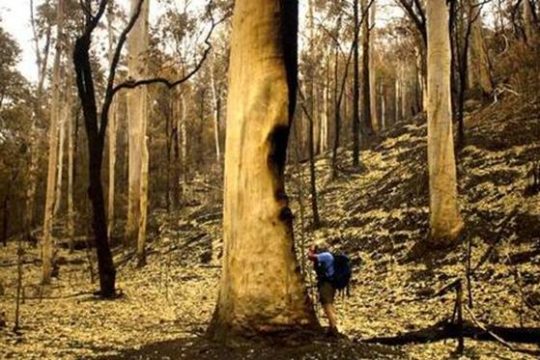

Blue Gum Forest burnt in 2006 by an RFS hazard reduction. [Source: Photo by Nick Moir of Blue Mountains Botanist Dr Wyn Jones inspecting the fire damage to the Blue Gums, dated 2006122 in the Sydney Morning Herald, >https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/2006-grose-valley-fire-a-cover-up/] Blue Gum Forest burnt in 2006 by an RFS hazard reduction. [Source: Photo by Nick Moir of Blue Mountains Botanist Dr Wyn Jones inspecting the fire damage to the Blue Gums, dated 2006122 in the Sydney Morning Herald, >https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/2006-grose-valley-fire-a-cover-up/]

Grose Valley Arson of December 2019

Then Last month in December 2019 the government Baby Boomer arsonists ultimately had their way. On 16th December, the Gospers Mountain Fire crossed the Bells Line of Road and spotted into the Grose Valley. By 21st December the Blue Gum Forest was gone.

Media warped termed ‘lava waterfall‘ up the Blackheath escarpment in the Grose Valley. Media warped termed ‘lava waterfall‘ up the Blackheath escarpment in the Grose Valley.

[Source: Saturday 20121221, ^https://www.facebook.com/BlueMountainsExplore/]

Months prior, a remote rural pastoral property near Gospers Mountain somehow within the Wollemi Wilderness, created an ignition on Saturday 26th October 2019.

Gospers Mountain showing remote historic rural cattle paddocks deep within the Wollemi Wilderness. The Australian Government calls it a national park but takes no accountability by delegating custodial protection but no funding to the state government of New South Wales. Gospers Mountain showing remote historic rural cattle paddocks deep within the Wollemi Wilderness. The Australian Government calls it a national park but takes no accountability by delegating custodial protection but no funding to the state government of New South Wales.

Gospers Mountain is 50km NE of the locality of Bell as the crow flies or fire spreads. Officially declared started by dry lighting in the ‘national park’ on a hot Saturday, this crime of arson and subsequent government firefighting neglect remains secretive. So NSW Police Bush Arson Squad ‘Strike Force Toronto‘ where are you on this – honest or corrupted by the Premier and RFS?

The RFS Gospers Mountain Fire has been the largest bushfire in New South Wales state history. The total number of days between Saturday, October 26th, 2019 and Monday, December 16th, 2019 was 51 days; or one month and 20 days. Over 51 days the fire was allowed to become a ‘megafire’ (likely a new Macquarie Dictionary term for 2020) and ultimately the largest single bushfire in Australia’s history – incineratingmore than 500,000 hectares of bush wilderness…

Of course the Gospers Mountains Fire was left to spread into a mega-fire and to cross over the Bells Line of Road some 50km south-west.

So what did the RFS do for PR but rebrand the Gospers Mountains Fire southerly spread as a new Grose Valley Fire, and to so to be allowed to incinerate down the escarpment into the Grose Valley and to incinerate the Cradle of Conservation – the Blue Gum Forest.

As if RFS arsonists care a damn?

Now government paid white collar fire chiefs have had their way. Forest incineration complete. Easy-peasy till retirement.

Yes RFS let an ignition with a small plume of smoke rising in remote National Park inaccessible to fire trucks burn neglected for days and weeks, negligent of the consequences. What hazard predictably eventuates when ignored for weeks? From the RFS ignition detected at Gospers Mountain on Saturday 26th October 2019 bordering the World Heritage Wollemi National Park …to 16th December 2019 – what response and when was undertaken by the RFS as a supposed fire fighting service?

Truthful answer: Defacto hazard reduction because the bushfire was atthe time not immediately threatening human properties.

Then as normal, the wind picked up, and the wee plume of remote rising smoke morphed into a fire front, then inferno and then into Australia’s worst megafire on record.

Rural Fire Service (NSW) Commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons (aged 50) is ultimately responsible for the bushfire prevention, planning, resourcing, response for New South Wales outside metropolitan areas services by NSW Fire and Rescue. In our view the he has failed to protect rural NSW to the standards of urban NSW by failing to oversee a government entrusted fire-fighting authority to promptly detect, respond to and extinguish bushfires in a timely manner.

His predecessor also repeatedly failed in his bushfire plan and following the 2006 Grose Valley Pyrocumulus of 2006 promptly skedaddled back to Perth to WA’s chagrin and cost (on record).

If only the ‘000’ Fire Brigade extinguisher standard applied outside metropolitan Australia? If only the ‘000’ Fire Brigade extinguisher standard applied outside metropolitan Australia?

No longer enjoying the benefits of the tourism economy. The Grand Canyon Track closed since 30 November 2019 and still closed on 21 January 2020 -peak tourist season. No longer enjoying the benefits of the tourism economy. The Grand Canyon Track closed since 30 November 2019 and still closed on 21 January 2020 -peak tourist season.

What had started as a small plume of smoke off Army Road on Saturday 26th October on a rural property near Gospers Mountain some sixty kilometres to the north, had been allowed to burn away into the World Heritage of the Wollemi National Park wilderness for weeks. It was allowed to destroy all the magnificent Wollemi wilderness from end to end.

By the time the bushfire had crossed to the southern side of the Bells Line of Road 50km south, the RFS changed their pet name of the ‘Gospers Mountain Fire’ to being dubbed the ‘Grose Valley Fir’e. Why not? That was the goal – defacto hazard reduction.

The iconic Blue Gum Forest in the Grose Valley of the Blue Mountains was left to incinerate by the New South Wales Government in December 2019. They did what Williamson in the 1920s failed to achieve. [Source: Editor, The Habitat Advocate, photo taken from Valley View Lookout 100m north of Evans Lookout, 20200121] The iconic Blue Gum Forest in the Grose Valley of the Blue Mountains was left to incinerate by the New South Wales Government in December 2019. They did what Williamson in the 1920s failed to achieve. [Source: Editor, The Habitat Advocate, photo taken from Valley View Lookout 100m north of Evans Lookout, 20200121]

Once World Heritage values of the Grose Valley have now gone up in smoke. The icon Blue Gum Forest has been incinerated yet again since the previous RFS successful attempt in November 2006. No wonder the place is very very quiet. All the wildlife is dead and the native birds have flow away.

Close up of the Blue Gum Forest from near Evans Lookout (top of photo) showing the canopy of Eucalyptus deanei incinerated; not much left of the forest in the foreground either. [Source: Editor, The Habitat Advocate, photo taken from Valley View Lookout 100m north of Evans Lookout, 20200121] Close up of the Blue Gum Forest from near Evans Lookout (top of photo) showing the canopy of Eucalyptus deanei incinerated; not much left of the forest in the foreground either. [Source: Editor, The Habitat Advocate, photo taken from Valley View Lookout 100m north of Evans Lookout, 20200121]

This time they have succeeded in total incineration – their goal of converting hazardous forest ecology into anthropocentric manageable parkland has long been misunderstood by ideologically hopeful environmentalists. The misnomer National Parks and Wildlife Service (NSW) ethically should now do the right thing and re-brand itself State Parks Administration Service it commercially is.

More than 80% of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and more than 50% of the Gondwana world heritage rainforests of northern New South Wales and southern Queensland have been burnt in Australia’s worst bushfire disaster in history. The scale of the disaster is such that it could affect the diversity of eucalypts for which the Blue Mountains world heritage area is recognised, said John Merson, the executive director of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute.

The Habitat Advocate has written to UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre expressing shock, outrage and anger over government mismanagement and contempt for Blue Mountains ecology through abject neglect in bushfire response. With most of the world heritage incinerated, we have questioning the status of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area as these values apply to Eucalypt diversity, since 80% has been incinerated.

UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre has expressed concern about the scale and intensity of bushfire damage to the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area and to the Gondwana Rainforests and has asked the Australian government whether it should de-list their world heritage status. In a statement on its website, UNESCO said members of the media and civil society had asked about the bushfires affecting the areas inscribed on the world heritage list as the “Gondwana rainforests of Australia”. The forests are considered a living link to the vegetation that covered the southern super-continent Gondwana before it broke up about 180m years ago.

According to UNESCO:

“The World Heritage Centre is currently verifying the information with the Australian authorities, in particular regarding the potential impact of the fires on the outstanding universal value of the property. The Centre has been closely following-up on this matter and stands ready to provide any technical assistance at the request of Australian authorities.”

Blue Mountains World Heritage is a misnomer and a sick joke. This RFS blackened moonscape now blankets 80% of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. Incinerated, quite dead, quiet, subsequently oven baked in the scorching sun and now sterilised. The tamed moonscape is far easier to manage for the Parks Service, like Centennial Park. [Source: Editor, The Habitat Advocate, photo taken 20200121 of escarpment track near Evans Lookout.] Blue Mountains World Heritage is a misnomer and a sick joke. This RFS blackened moonscape now blankets 80% of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. Incinerated, quite dead, quiet, subsequently oven baked in the scorching sun and now sterilised. The tamed moonscape is far easier to manage for the Parks Service, like Centennial Park. [Source: Editor, The Habitat Advocate, photo taken 20200121 of escarpment track near Evans Lookout.]

Further Reading:

[1] ‘Grose Wilderness‘, by historian Andy Macqueen, Blue Mountains Nature website, ^https://bmnature.info/conservation-wilderness-grose.shtml

[2] ‘Wild About Wilderness‘ in ‘The Ways of the Bushwalker’, 2007, a book by Melissa Harper, published by University of New South Wales Press Ltd, pp.258-259.

[3] ‘Burning Issues – Fire in the Grose Valley‘, 200612, by Ian Brown, Mount Victoria, ^http://www.abc.net.au/cm/lb/6276108/data/grose-fire-gazette-data.pdf

[4] ‘2006 Grose Fires: the realisation of a tragedy‘, 20120712, by Editor, The Habitat Advocate, >https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/2006-grose-fires-the-realisation-of-a-tragedy/

[5] ‘2006 Grose Valley Fire – a cover up?‘, 20101217, by Editor, The Habitat Advocate, >https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/2006-grose-valley-fire-a-cover-up/

[6] ‘Bushwalking and the Conservation Movement‘, in printed book ‘Blue Mountains – Pictorial Memories, 1998, by John Low AO, pp. 96-97, published by Kingsclear Books

[7] ‘2006 Grose Fire – Log of Media Releases‘, by Editor, The Habitat Advocate, >https://www.habitatadvocate.com.au/2006-grose-fire-log-of-media-releases/

[8] ‘The monster’: a short history of Australia’s biggest forest fire‘ (Gospers Mountain ‘mega fire’), 20191220, by Harriet Alexander and Nick Moir, Sydney Morning Herald newspaper, ^https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/the-monster-a-short-history-of-australia-s-biggest-forest-fire-20191218-p53l4y.html

[9] ‘It’s heart-wrenching’: 80% of Blue Mountains and 50% of Gondwana rainforests burn in bushfires‘, 20200116, by Lisa Cox and Nick Evershed, The Guardian newspaper, ^https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jan/17/its-heart-wrenching-80-of-blue-mountains-and-50-of-gondwana-rainforests-burn-in-bushfires

[10] David Noble Blog, articles tag=Blue Gum Forest, ^http://www.david-noble.net/blog/?tag=blue-gum-forest

[11] ‘Lessons from the 1957 Leura Bushfire‘, 20190912, The Australian Bushfire Building Conference website, ^https://bushfireconference.com.au/news/the-1957-leura-bushfire/. Also check: ^http://www.fire.bmwhi.org.au/

But tell the RFS. But tell the RFS.

All they had to do was to put the small plume out when it started, like the proper fire brigade does in metropolitan Australia.

Tags: Blue Gum Forest, Blue Mountains, Cradle of Conservation, flammagenitus, Gospers Mountain, Grose Pyrocumulus, NPWS, RFS, Strike Force Toronto, Wollemi Wilderness

Posted in SAVE HABITAT FROM GOVERNMENT ARSON, Threats from Bushfire | No Comments »

Add this post to Del.icio.us - Digg

Tuesday, March 5th, 2013

Blue Gum Forest in 1931

An innocent time in fading history – when Platypus were plentiful, bred and swum freely in the Grose River Blue Gum Forest in 1931

An innocent time in fading history – when Platypus were plentiful, bred and swum freely in the Grose River

Party of Sydney Bush Walkers in Blue Gum Forest, circa October 1931

[Source: Photo by Alan Rigby, Blue Gum Forest Committee,

from ‘Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness’ (1997), book by Andy Macqueen, p.256, click image to enlarge]

.

In 2006, the New South Wales (Government’s) Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) or ‘Parks‘, being delegated by the Australian Government for absolute responsibility for ecologically protecting the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (BMWHA), so under-resourced its firefighting effort as to deliberately let the Grose Valley burn out of control.

Senior management well knew, like their firefighting partners the Rural Fires Service, that legal and political accountabilty extended ONLY to protecting private properties and human lives. So this they did and so let 14,070 hectares of the Grose Valley and adjoining land burn. It saved them the cost and effort of future ‘hazard’ reduction.

Parks adopted a cost-saving abandonment strategy (making management look efficient) which it labels deliberate bushfire as ‘fire ecology‘ and so by deliberate under-resourcing of fire fighting against two documented ignitions to then let burn into the Grose Valley and the Blue Gum Forest. These two ignitions (1) a purported lightning strike on Burra Korain Ridge and (2) a deliberate RFS ‘hazard’ reduction burn along the south side of Hartley Vale Road – both outside the BMWHA, were the instigators of the 2006 Grose Fire.

It was all hushed up, despite public calls for an independent public enquiry. Both the RFS Commissioner and Blue Mountains Local Member at the time said no to the public calls for an independent public enquiry. Why?

.

Grose Valley Fire aftermath at Govetts Leap, Blackheath Grose Valley Fire aftermath at Govetts Leap, Blackheath

[Photo by Editor 20061209, click image to enlarge, free in public domain]

.

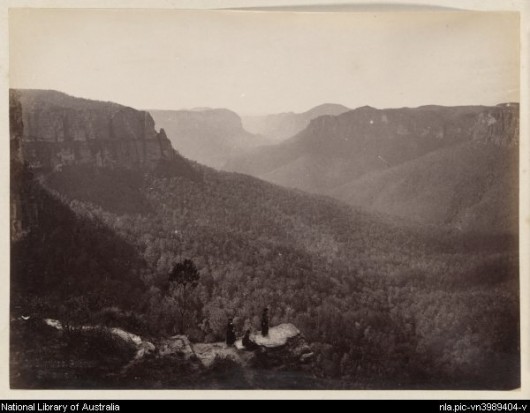

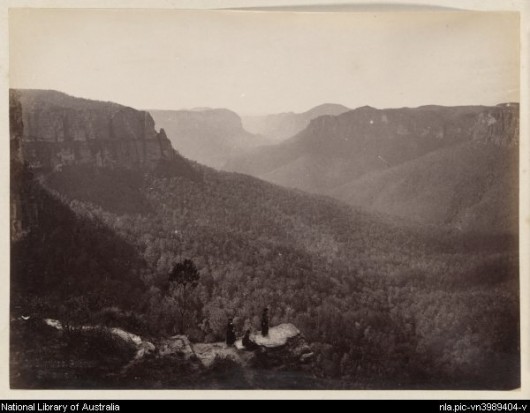

New South Wales colonists, once they stumbled across the spectacular Grose Valley deep in the Blue Mountains, were in awe in sublime wonder. So it was that initially that the Grose Valley as far back as in 1875 became reserved as a ‘national spectacle’.

But many wanted to dam it – ^Robber Barons and prevailing industrialist politicians of the times had the same view of ‘progress‘ being a colonial right and unquestioningly superior to Nature. They tried to put the railway through the Grose, to mine it, to log it or else to farm it; all so long as the vast ‘resource’ was not neglected for ‘progress‘.

.

Grose Valley, view from Govett’s Leap in 1886 by Charles Bayliss

Note the women in the foreground in the Victorian dress of the day

[Source: Part of Lindt, J. W. (John William), 1845-1926,

National Library of Australia, 1 digital photograph : b&w,

^http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3989404] Grose Valley, view from Govett’s Leap in 1886 by Charles Bayliss

Note the women in the foreground in the Victorian dress of the day

[Source: Part of Lindt, J. W. (John William), 1845-1926,

National Library of Australia, 1 digital photograph : b&w,

^http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn3989404]

.

Thankfully, this majestic Grose Valley and its ancient icon Blue Gum Forest were saved the axe in 1931. But is was only marginally due to the persistent campaigning efforts of a small dedicated group of bushwalkers passionate about saving this forest back even in the midst of The Great Depression.

If ever a case were not truer:

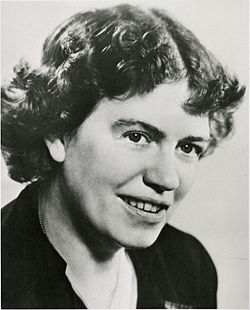

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

~ American cultural anthropologist, Margaret Mead

. Margaret Mead, 1901–1978 Margaret Mead, 1901–1978

.

‘The Blue Gum‘ was ultimately saved by the generous personal donation by allied bushwalker W.J. Cleary of £80 [perhaps $20,000 in today’s value *] to purchase the rights to the land from the pastoralist Clarrie Hungerford in February 1932.

.

Significantly, their dedicated act of environmental conservation is arguably the first environmental campaign in Australia’ history. ‘The Blue Gum‘ since then and for eighty years since has been affectionately known amongst environmentalists as ‘The Cradle of Conservation‘.

[Ed: * CALCULATION: In 1930, the average yearly wage for ordinary Australian workers was roughly £220, source: ^http://guides.slv.vic.gov.au/content.php?pid=14258&sid=95522. So given that today’s average yearly salary in Australia is about $56,000 (Source: ^http://www.abs.gov.au), the calculation is 80/220 * 56,000 = $20,000]

.

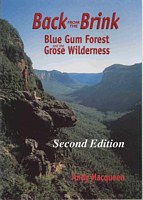

<<Everyone has been to the lookouts. Many have been to the Blue Gum Forest, deep in the valley– but few know the remote & hidden recesses of the labyrinth beyond. Here, an hour or two from Sydney, is a very wild place.

The Grose has escaped development. There have been schemes for roads, railways, dams, mines & forestry, but the bulldozers have been kept out. Instead, the valley became the Cradle of Conservation in New South Wales when it was reserved from sale in 1875 – an event magnificently reinforced in 1931 when a group of bushwalkers were moved to save the Blue Gum Forest from the axe.

Local author, Andy Macqueen, has been an enthusiastic bushwalker and conservationist since the 1960’s. In 1997, he published his book, ‘Back from the Brink: Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Wilderness‘, aptly titled in telling the true story of how the Blue Gum Forest was saved from destruction.

Macqueen’s well researched book tells in detail the story of the whole Grose Wilderness experience and of the Blue Gum Forest rescue story in particular. It tells about the many different people who have visited this wilderness: Aborigines, explorers, engineers, miners, track builders, bushwalkers, canyoners, climbers…those who have loved it, and those who have threatened it.>>

Available from Megalong Books, Leura in the Blue Mountains

^http://shop.megalongbooks.com.au/bookweb/details.cgi?ITEMNO=9780646476957

^http://www.megalongbooks.com.au/ Available from Megalong Books, Leura in the Blue Mountains

^http://shop.megalongbooks.com.au/bookweb/details.cgi?ITEMNO=9780646476957

^http://www.megalongbooks.com.au/

.

Other books about the Blue Mountains:

^http://www.lamdhabooks.com.au/bluemountainscatalogue.htm

.

Hazard Reduction Revenge

.

A decade later, in 1940 the Grose Valley was subjected to a bushfire; however its cause, circumstances and extent of damage are unknown by The Habitat Advocate.

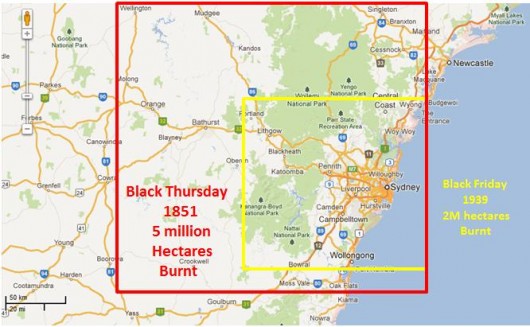

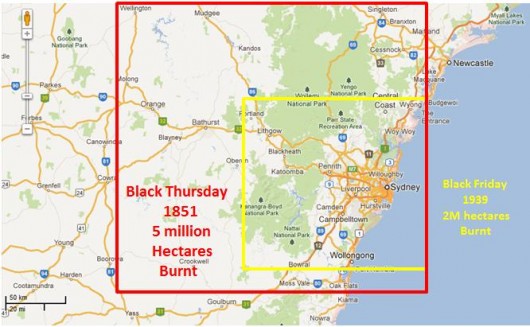

This bushfire occurred only a year after the devastating 1939 Bushfires of ‘Black Friday‘ across Victoria, which is collectively considered one of the worst natural bushfires (wildfires) in the world. Almost 20,000 km² (2 million hectares) was burnt, 71 people perished and several significant native forests were destroyed (Victorian Alps, Yarra Ranges, Otway Ranges, Grampians and Strzelecki Ranges) and the townships of Dromana, Healesville, Kinglake, Marysville, Narbethong, Warburton, Warrandyte, Yarra Glen, Hill End, Nayook West, Matlock, Noojee, Omeo, Woods Point, Pomonal and Portland.

The subsequent Royal Commission, under Judge L.E.B Stretton (known as the Stretton Inquiry), attributed blame for the fires to careless burning, such as for campfires and land clearing.

It was the second major bushfire tragedy since the 1851 Black Thursday Bushfires which wiped out 5 million hectares of Victoria.

. Bushfire Tragedy in aggregated geographical context.

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat? Bushfire Tragedy in aggregated geographical context.

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat?

.

More recently a disturbing ‘bushphobic culture‘ has produced a need to burn it for its burning sake. One must wonder whether our society has indeed advanced, matured or just ‘progressed‘ its colonialism?

.

Grose Valley Bushfire of 25th October 2002

[Source: Image by Paul Cosgrave, National Library of Australia, 2003,

1 digital photograph : b&w.http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an24966058] Grose Valley Bushfire of 25th October 2002

[Source: Image by Paul Cosgrave, National Library of Australia, 2003,

1 digital photograph : b&w.http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-an24966058]

.

In 2006, the Grose Valley was incinerated in a massive firestorm and this time the fire ripped through the Blue Gum Forest..

.

. Firefighters watching the escalating bushfire incinerating the Grose Valley below

22 November 2006 – the day before the Grose Firestorm

Picture: Brad Newman, in The Australian. Firefighters watching the escalating bushfire incinerating the Grose Valley below

22 November 2006 – the day before the Grose Firestorm

Picture: Brad Newman, in The Australian.

.

<<Residents in towns across NSW waited for the worst last night as bushfires burned thousands of hectares across the state and dry conditions were forecast for almost the entire continent for another week.

Spot fires from a 10-day-old bushfire burning in the Blue Mountains came within a few hundred metres of houses in Blackheath. Katoomba, Mount Tomah and Lawson and other towns in the region were also under threat from the worst bushfire in the nation.

“There was virtually no cloud over the entire continent,” said Julie Evans from the NSW Bureau of Meteorology of the dry conditions expected to continue across most of Australia in the coming week.

As mild weather and a cool change provided relief to firefighters in South Australia and Victoria, smoke from the Blue Mountains blaze, which was last night largely contained in the Grose Valley, rose more than 12km into the air, causing ash to fall on central Sydney and effectively creating its own weather system.

Watching from a helicopter above the flames, National Parks and Wildlife Service acting regional manager Kim De Govrik said the explosion as the fire crowned in the tree-tops around the Banks Wall cliff-face was “like a nuclear bomb going off”.

Sparks ignited fires up to 15km away, near Faulconbridge, home of Rural Fire Service Commissioner Phil Koperberg, who is directing the operation to contain the state’s fires.

“By tomorrow morning, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to expect that there will be additional fires around the countryside,” Mr Koperberg said yesterday.

About 2000 firefighters spent the day battling about 44 fires across NSW, five of which the RFS said it was unable to contain. Molong enjoyed a reprieve after a late wind shift caused a fire to change direction just 4km from the central-western town. Residents were relocated to a community centre last night, while an unoccupied house and vehicle were destroyed by the fire.

The RFS met residents in the Hawkesbury and Goulburn regions early last night to update them on the fires and what they can do to prepare their homes.

The bushfires also led to blackouts across Sydney. Just a week after the city endured its coldest November night in a century, the city sweltered through its third-hottest November day in 25 years — the official maximum temperature was 38.4C. Dozens of suburbs in the city’s west and southwest were affected by the outages, as were large sections of the CBD.

The NSW parliament was twice plunged into darkness as the power surges hit in the late afternoon, with the second one lasting several minutes.

Mild weather led the bushfire threat across South Australia to fall. CFS spokeswoman Krista St John said the state’s southeast had been hardest hit, with fires burning about 8500ha.

In Victoria, a cool change helped firefighters bring the state’s larger fires under control, although lightning strikes ignited several smaller fires in the west of the state.>>

.

[Source: ‘Fires and dry conditions have residents fearing the worst’, 20061123, by Dan Box and Simon Kearney; additional reporting by Padraig Murphy and AAP, The Australian newspaper, ^http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/fires-and-dry-conditions-have-residents-fearing-the-worst/story-e6frg6o6-1111112569927]

.

23 November 2006

14,070 hectares of precious Blue Mountains habitat incinerated

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat? 23 November 2006

14,070 hectares of precious Blue Mountains habitat incinerated

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat?

.

The home that Parks had it in for … the Blue Gum Forest’s fire-scarred trees,

some of which have graced the Grose Valley for hundreds of years.

The home that Parks had it in for … the Blue Gum Forest’s fire-scarred trees,

some of which have graced the Grose Valley for hundreds of years.

A defacto hazard reduction burn.

[Photo: Nick Moir, ^http://www.nickmoirphoto.com/]

.

<<More than 70 years ago this forest inspired the birth of the modern Australian conservation movement. Today Blue Gum Forest stands forlorn in a bed of ash.

But was it unnecessarily sacrificed because of aggressive control burning by firefighters focused on protecting people and property? That is the tough question being asked by scientists, fire experts and heritage managers as a result of the blaze in the Grose Valley of the upper Blue Mountains last month.

As the fate of the forest hangs in the balance, the State Government is facing demands for an independent review of the blaze amid claims it was made worse by control burning and inappropriate resources.

This comes against a backdrop of renewed warnings that Australia may be on the brink of a wave of species loss caused by climate change and more frequent and hotter fires. There are also claims that alternative “ecological” approaches to remote-area firefighting are underfunded and not taken seriously.

In an investigation of the Blue Mountains fires the Herald has spoken to experienced fire managers, fire experts and six senior sources in four agencies and uncovered numerous concerns and complaints.

* It was claimed that critical opportunities were lost in the first days to contain or extinguish the two original, separate fires.

* Evidence emerged that escaped backburns and spot fires meant the fires linked up and were made more dangerous to property and heritage assets – including the Blue Gum Forest. One manager said the townships of Hazelbrook, Woodford and Linden were a “bee’s dick” away from being burnt. Another described it as “our scariest moment”. Recognising the risk of the backburn strategy, one fire officer – before the lighting of a large backburn along the Bells Line of Road – publicly described that operation as “a big call”.

It later escaped twice, advancing the fire down the Grose Valley.

.

- Concerns were voiced about the role of the NSW Rural Fire Service Commissioner, Phil Koperberg.

- Members of the upper Blue Mountains Rural Fire Service brigades were unhappy about the backburning strategy.

- There were doubts about the mix and sustainability of resources – several senior managers felt there were “too many trucks” and not enough skilled remote-area firefighters.

- Scientists, heritage managers and the public were angry that the region’s national and international heritage values were being compromised or ignored.

- There was anecdotal evidence that rare and even common species were being affected by the increased frequency and intensity of fires in the region.

- Annoyance was voiced over the environmental damage for hastily, poorly constructed fire trails and containment lines, and there were concerns about the bill for reconstruction of infrastructure, including walking tracks.

.

The fire manager and ecologist Nic Gellie, who was the fire management officer in the Blue Mountains for the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service during the 1980s and ’90s, says the two original fires could have been put out with more rapid direct attack.

“Instead, backburning linked up the two fires and hugely enlarged the fire area … what we saw would be more accurately described as headfire burning, creating hot new fire fronts. While it protected the town of Blackheath, the plateau tops burnt intensely – and that created new problems both for management of the fire and the protection of biodiversity.

“When extreme fire weather, hot days and high winds arrived as predicted, the expanded fire zone was still not fully contained – and that was the cause of most of the high drama and danger that followed.”

In that dramatic week, Mr Gellie confronted Mr Koperberg with his concerns that the commissioner was interfering with the management of the fire by pushing hard for large backburns along the northern side of towns in the Blue Mountains from Mount Victoria to Faulconbridge, along what is known in firefighting circles as the “black line”.

The Herald has since confirmed from numerous senior sources that “overt and covert pressure” from head office was applied to the local incident management team responsible for fighting the fire.

There were also tensions relating to Mr Koperberg’s enthusiasm for continuation of the backburning strategy along the black line – even when milder weather, lower fuel levels and close-in containment were holding the fire.

Several sources say the most frightening threat to life and property came as the fire leapt onto the Lawson Ridge on “blow-up Wednesday” (November 22) – and that those spot fires almost certainly came from the collapse of the convection column associated with the intensification of the fire by the extensive backburns.

.

The Herald has also confirmed that:

- The original fire lit by a lightning strike near Burra Korain Head inside the national park on Monday, November 13, could not be found on the first day. The following day, a remote area fire team had partly contained the fire – but was removed to fight the second fire. The original fire was left to burn unattended for the next couple of days;

.

- An escaped backburn was responsible for the most direct threat to houses during the two-week emergency, at Connaught Road in Blackheath. However, at a public meeting in Blackheath on Saturday night, the Rural Fire Service assistant commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons played down residents’ concerns about their lucky escape. “I don’t want to know about it. It’s incidental in the scheme of things.”

.

Mr Koperberg, who is retiring to stand as a Labor candidate in next year’s state elections, rejected the criticisms of how the fire was fought. He told the Herald: “The whole of the Grose Valley would have been burnt if we had not intervened in the way we did and property would have been threatened or lost. We are looking at a successful rather than an unsuccessful outcome.

“It’s controversial, but this is world’s best backburning practice – often it’s the only tool available to save some of the country.”

The commissioner rejected any criticism that he had exerted too much influence. “As commissioner, the buck stops with me. I don’t influence outcomes unless there is a strategy that is so ill-considered that I have to intervene.”

Mr Koperberg said it was “indisputable and irrefutable” that the Blue Mountains fire – similar to fires burning now in Victoria – was “unlike any that has been seen since European settlement”, because drought and the weather produced erratic and unpredictable fire behaviour.

The district manager of the Blue Mountains for the Rural Fire Service, Superintendent Mal Cronstedt, was the incident controller for the fire.>>

.

[Source: ‘The ghosts of an enchanted forest demand answers’, 20061211, by Gregg Borschmann, Sydney Morning Herald, p.1, ^http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/the-ghosts-of-an-enchanted-forest-demand-answers/2006/12/10/1165685553891.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap2]

.

Grose Valley’s bushphobic habitat incinerated

because in the minds of Parks and the Rural Fire Service it was a fuel hazard

Click image to enlarge,

Photo by Editor 20070106, free in public domain Grose Valley’s bushphobic habitat incinerated

because in the minds of Parks and the Rural Fire Service it was a fuel hazard

Click image to enlarge,

Photo by Editor 20070106, free in public domain

.

<<A bushfire scars a precious forest – and sparks debate on how we fight fire in the era of climate change, writes Gregg Borschmann.

The ghosts of an enchanted forest demand answers

“Snow and sleet are falling on two bushfires burning in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney.”

ABC Radio, November 15: The news report was almost flippant, something that could happen only in Dorothea Mackellar’s land of drought and flooding rains. Later that evening, two weeks from summer, Sydney had its coldest night in more than a century.

Over the past month – as an early summer collided with a late winter and a decade-long drought – NSW and Victoria have battled more than 100 bushfires.

But of them all, last month’s Blue Mountains blaze reveals tensions and systemic problems that point to a looming crisis as bushfire fighters struggle to protect people, property, biodiversity and heritage values in a world beset by climate change.

The tensions have always been there – different cultures, different ways of imagining and managing the landscape. Perhaps they are illustrated by a joke told by two Rural Fire Service crew in the Blue Mountains. “How does the RFS put out a fire in your kitchen? By backburning your sitting room and library.” The joke barely disguises the clash between the imperative of saving lives and homes, and the desire to look after the land, and the biodiversity that underpins our social and economic lives.

For fire managers, whose first priority will always be saving people and property, the equation has become even more tortured with a series of class actions over fires in NSW and the ACT. As one observer put it: “These guys are in a position where they’re not going to take any chances. No one will ever sue over environmental damage.”

For bushfire management the debate tentatively started a couple of decades ago. The challenge was to do what poets, writers and painters have long grappled with – coming to terms with a country whose distinctiveness and recent evolutionary history have been forged in fire.

Drought and climate change now promise to catapult that debate to centre stage.

It is perhaps no accident that such a defining fire has occurred in one of the great amphitheatres of the Australian story, the Grose Valley in the upper Blue Mountains. Charles Darwin passed by on horseback in 1836, and described the valley as “stupendous … magnificent”.

The Grose has long been a microcosm of how Australians see their country. In 1859 some of the first photos in Australia were taken in the valley. Proposals for rail lines and dams were forgotten or shelved. The first great forest conservation battle was fought and won there in 1931-32.

But now the valley is under threat from an old friend and foe – fire.

Ian Brown has worked on dozens of fires in the Blue Mountains. He is a former operations manager for the National Parks and Wildlife Service.

“All fires are complex and difficult, and this sure was a nasty fire … But we need lots of tools in the shed. Those hairy, big backburns on exposed ridges so close to a blow-up day with bad weather surprised me. Frightened me even.”

For Brown, even more worrying is the trend.

“Parts of the Grose have now burnt three times in 13 years and four times in 24 years. Most of those fires started from arson or accident. Many of the species and plant communities can’t survive that sort of hammering.”

Ross Bradstock, a fire ecologist, agrees. Professor Bradstock is the director of the new Centre for the Environmental Risk Management of Bushfires at the University of Wollongong, which is funded by the Department of Environment and Conservation and the Rural Fire Service. He says Australia stands out as one of the countries whose vegetation may be most affected by climate change.

Bradstock says that in south-eastern Australia the potential for shifts in fire frequency and intensity are “very high … If we’re going to have more drought we will have more big fires.”

But the story is complicated and compounded by the interaction between drought and fire. The plants most resistant to fire, most able to bounce back after burning, will be most affected by climate change. And the plants that are going to be advantaged by aridity will be knocked over by increased fire frequency. “In general, the flora is going to get whacked from both ends – it’s going to be hit by increased fire and climate change. It’s not looking good.”

Wyn Jones, an ecologist who worked for the wildlife service, says the extremely rare drumstick plant, Isopogon fletcheri, is a good example. There are thought to be no more than 200 specimens, restricted to the upper Grose. Last week, on a walk down into the Blue Gum Forest, Jones found three – all killed by the fire.

The NSW Rural Fire Service Commissioner, Phil Koperberg, has been a keen supporter of Bradstock’s centre. Asked if he agreed with the argument that the Grose had seen too much fire, Mr Koperberg replied: “It’s not a comment I disagree with, but had we not intervened in the way we did, the entire Grose Valley would have been burnt again, not half of it.”

The great irony of the fire is that it was better weather, low fuels and close-in containment firefighting that eventually stopped the fire – not big backburns.

Remote area firefighting techniques have been pioneered and perfected over recent decades by the wildlife service. In 2003 a federal select committee on bushfires supported the approach. It recommended fire authorities and public land managers implement principles of fire prevention and “rapid and effective initial attack”.

Nic Gellie, a fire ecologist and former fire manager, has helped the wildlife service pioneer ecological fire management. The models are there – but he says they have not been used often enough or properly.

Doubts have been expressed about the sustainability of the current remote area firefighting model. It is underfunded, and relies on a mix of paid parks service staff and fire service volunteers. Most agree the model is a good one, but not viable during a longer bushfire relying on volunteers.

The Sydney Catchment Authority pays $1 million for Catchment Remote Area Firefighting Teams in the Warragamba water supply area. It has always seemed like a lot of money. But it looks like a bargain stacked against the estimated cost of $10 million for the direct costs and rehabilitation of the Grose fire.

Curiously, one unexpected outcome of the great Grose fire may be that the valley sees more regular, planned fire – something the former wildlife service manager Ian Brown is considering.

“If climate change means that the Grose is going to get blasted every 12 years or less, then we need more than just the backburning strategy. We need to get better at initial attack and maybe also look at more planned burns before these crises. But actually getting those burns done – and done right – that’s the real challenge.”

It may be the only hope for Isopogon fletcheri.

Asked if he would do anything differently, Mr Cronstedt answered: “Probably.” But other strategies might have also had unknown or unpredictable consequences, he said.

Jack Tolhurst, the deputy fire control officer (operations) for the Blue Mountains, said: “I am adamant that this fire was managed very well. We didn’t lose any lives or property and only half the Grose Valley was burnt.”

Mr Tolhurst, who has 50 years’ experience in the Blue Mountains, said: “This fire is the most contrary fire we have ever dealt with up here.”

John Merson, the executive director of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute, said fire management was being complicated by conditions possibly associated with climate change.

“With increased fire frequency and intensity, we are looking at a fundamental change in Australian ecosystems,” he said. “We will lose species. But we don’t know what will prosper and what will replace those disappearing species. It’s not a happy state. It’s a very tough call for firefighters trying to do what they think is the right thing when the game is no longer the same.

“What we are seeing is a reflex response that may no longer be appropriate and doesn’t take account of all the values we are trying to protect.”>>

.

[Source: ‘ The burning question’, 20061211, by Gregg Borschmann (producer for ABC Radio National), Sydney Morning Herald, p.10, ^http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/the-burning-question/2006/12/10/1165685553945.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap1]

.

So why are Australian wildlife hard to find in their natural bush habitat?

.

Saturday, July 7th, 2012

The fire tragedy afflicted Australia’s legendary ‘Conservation Cradle’

A scorched Grose Valley from Evan’s Lookout, looking north up Govett’s Gorge

(Photo by Editor taken 20061209, free in public domain. Free Large Image) The fire tragedy afflicted Australia’s legendary ‘Conservation Cradle’

A scorched Grose Valley from Evan’s Lookout, looking north up Govett’s Gorge

(Photo by Editor taken 20061209, free in public domain. Free Large Image)

.

A heritage tragedy unfolds

.

A simple lighting stike ignited remote bushland in rugged terrain within the Blue Mountains National Park, over 5km north of the township of Blackheath on 20061113.

Innocuously, the ignition started off on hilly Burra Korain Ridge,

It was far from settlement but during relatively calm weather and low temperature, so it was not suppressed but ‘monitored’

..then the wind picked up. Innocuously, the ignition started off on hilly Burra Korain Ridge,

It was far from settlement but during relatively calm weather and low temperature, so it was not suppressed but ‘monitored’

..then the wind picked up.

.

It and a second ignition west were allowed to continue burning for days until they eventually coalesced with compounded backburning into a firestorm some ten days later down in the Grose Valley. On 20061122, the prized Grose Valley and its iconic and precious Blue Gum Forest were incinerated under a pyrocumulus cloud of towering wood smoke that could be seen from the Sydney coast a hundred kilometres away. Some 14,070 hectares of National Park habitat was burnt. The tragedy did not so much as ‘strike‘ from the lighting itself, but as Blue Mountains residents we saw it ‘unfold‘ over many days and nights under the trusteeship of Bushfire Management.

.

..ten days later

The pyrocumulus cloud of a screaming, dying Grose Valley precious to many, including wildlife The pyrocumulus cloud of a screaming, dying Grose Valley precious to many, including wildlife

The Grose Valley and its Blue Gum Forest and wildlife burning to death on 20061122

A greenhouse gas estimate was not taken.

.

Community shock, sadness and overwhelming sense of loss

.

How was this allowed to happen?

In the days that followed, many Blue Mountains residents and especially the many conservationists familiar with the Grose Valley and Blue Gum Forest over many years became deeply shocked at learning about the loss of this magnificent sacred preserved forest – its tall 300+ year old rare Blue Gums (Eucalytus deanii).

Without knowledge of personal accounts, one respects that the dramatic scenes of the smoke and fire inflicted personal trauma with many, given so many people’s long and established personal knowledge, affinity, love, awe and respect for..

‘The Blue Gum‘

.

The Habitat Advocate reaches out to these people (doesn’t matter the fact that years have passed) and we choose to express the view of a need to tell truths and to seek some sense of learned maturity from it all. For the Grose Valley contained many tracks, many walks and many special places if one knew where to look. Popes Glen and from Govetts Leap down under Bridal Veil following the popular Rodriguez Pass to Junction Rock then Acacia Flat and the Blue Gum Forest in the heart of the Grose. Many special places includes Beauchamp Falls, Docker Buttress, Pulpit Rock, Lockley Pylon, Anvil Rock lookout, Perrys Lookdown, Hanging Rock, Pierces Pass, Asgard Swamp, and the inaccessible Henson Glen and David Crevasse gorge.

To this editor, the return in 2007 to a previously sacred special, but incinerated Neates Glen was emptying in spirit. There was heartfelt shock and dismay by many local conservationists familiar with the iconic Blue Gum Forest who became deeply saddened by the tragedy.

Neates Glen, as it was Neates Glen, as it was

But since incinerated, not by the wildife, but by deliberately lit ‘backburning’

.

Phone calls and emails were exchanged with many locals wanting to know the extent of the damage and whether ‘the Blue Gum‘ could recover. The original fire had been fanned westward from Burra Korain Head spotting along the Blackheath Walls escarpment, but then decended and burnt through Perrys Lookdown, Docker Buttress and down and through the Blue Gum. Deliberately lit backburns had descended and burnt out Pierces Pass (Hungerfords Track) through rainforest into the Grose and everyone had seen the pyrocumulus mushroom cloud towering 6000 feet above the Grose on the 22nd.

There was an immense sense of loss. The relatively small Blue Gum Forest, perhaps just several hectares, was unique by its ecological location, by its grand age and by its irreplaceability. The sense of loss was perhaps more pronounced amongst the more mature conservationists, now lesser in number, who knew its original saviours of the 1930s – Alan Rigby, Myles Dunphy and other dedicated bushwalkers who had championed to save it from logging 81 years ago.

The conservation heritage of The Blue Gum Forest dates back to Australia’s earliest conservation campaign from 1931

For this reason ‘The Blue Gum Forest’ has been passionately respected as

Australia’s ‘Cradle of Conservation’ The conservation heritage of The Blue Gum Forest dates back to Australia’s earliest conservation campaign from 1931

For this reason ‘The Blue Gum Forest’ has been passionately respected as

Australia’s ‘Cradle of Conservation’

.

The region is home to threatened or rare species of conservation significance living within the rugged gorges and tablelands, like the spotted-tailed quoll, the koala, the yellow-bellied glider, the long-nosed potoroo, the green and golden bell frog and the Blue Mountains water skink. Many would have perished in the inferno, unable to escape. The Grose is a very quiet and sterile place now, with only birds. But to the firefighters, these were not human lives or property.

.

Deafening silence from the ‘Firies’ naturally attracted community enquiry and suspicion

.

The day after the firestorm that enveloped the Grose Valley, the wind subsided and from 20061123 through to the final mopping up date of 20061203, the 2006 Grose Bushfire and its many ember spotfires came under bushfire management control and were ultimately extinguished or else considered to be ‘benign‘.

It is important to note that during the entire bushfire event from 20061113 through to 20061203, only NSW Rural Fire Service ‘Major Fire Updates’ on its website and headline journalism appeared in the local Blue Mountains Gazette newspaper. Initially, the community, conservationists and ‘firies’ were respectfully passive. In the immediate aftermath of the fire from 20061204 through to the weekly issue of the Blue Mountains Gazette on 20061129, the local community, conservationists and ‘firies’ were letter silent in the paper. It was a combination of shock, preoccupation with the emergency and respectful anticipation of communication from the bushfire authorities.

One can assume here that given the scale of the tragedy, many in the Blue Mountains community were respectfully patient in anticipation of an assured announcement from Bushfire Management or some communication process. But none eventuated.

.

Injustice

.

The following weekly issue of the Gazette was published on 20061129, but no communication from Bushfire Management. Only dismissive bureaucratic statements came from Parks and Wildlife’s Regional Director Geoff Luscombe with a tone suggesting minimal damage and business-as-usual.

This was the article:

6th Dec: ‘Park managers take stock as smoke clears’

[Source: ‘Park managers take stock as smoke clears’, by journalist Jacqui Knox, Blue Mountains Gazette, 20061206, ^http://www.bluemountainsgazette.com.au/news/local/news/general/park-managers-take-stock-as-smoke-clears/487936.aspx?storypage=0]

Ed: This RFS propaganda photo was included in the media article.

Govetts Leap Track (shown here) was deliberately lit by Bushfire Management Ed: This RFS propaganda photo was included in the media article.

Govetts Leap Track (shown here) was deliberately lit by Bushfire Management

.

‘Hundreds of fire-fighters are celebrating a return to normality this week after cooler weather and an intense two-week campaign by volunteers and professionals brought a fire in the Grose Valley under control.

According to the Rural Fire Service this good weather, combined with a thorough mop-up operation and ongoing infra-red monitoring, means flare-ups are unlikely. However the 15,000 hectare burnt area – including the iconic Blue Gum Forest – is likely to remain closed for the “foreseeable future” due to safety concerns and regeneration.

Geoff Luscombe, regional manager of the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), said the fact that only part of the Grose Valley burnt meant many animals had been able to seek refuge.

“Many of the Australian plants and animal species have learnt not only to survive fire but to exploit it,” he said. However he confirmed fears that the fire had burnt Blue Gum Forest – a Mecca for bushwalkers and conservationists in the heart of the Grose Valley.

“Blue gums aren’t a particularly fire-tolerant species,” he said. “Fire last burnt through Blue Gum in 1994. The effects of this fire we don’t know yet and we may not know for many months to come.”

A botanist has been sent to inspect the area and there could be ongoing monitoring. Mr Luscombe did not wish to comment on how the fire was handled due to a lengthy absence, but Inspector Jack Tolhurst from the Blue Mountains District Rural Fire Service has warded off any potential criticism.

“I think at the moment we should be looking at the positive,” said Inspector Tolhurst. “The fire is contained . . . It’s been a very long campaign but at the end of the day we haven’t lost any property or lives and half the Grose Valley at least remains intact.”

A fire that broke out near Zig-Zag Railway last week has also been contained. [Ed. According to inside reports, Zig Zag Railway Station was accidentally firebombed by an aerial helicopter attempting backburning].

“We’ve had a lot of help from a wide range of people. We’ve had wonderful support from the community . . . it was a wonderful effort from everyone.”

Meanwhile the hard work has only just begun for another group of dedicated volunteers. Blue Mountains WIRES are expecting to rescue a number of fire-affected native animals in coming months as they wander into residential areas for food and water.

“The arboreal animals – possums and gliders – they come to grief,” said chairperson Greg Keightly. “Birds suffer heat stress and smoke inhalation. They’re going to be flying around bewildered.”

He said residents who see native wildlife in urban areas should keep pets inside, provide water off the ground in a place safe from predators, and avoid the temptation to feed wildlife.

“Things come up for months after fires,” said Mr Keightley. “Do ring us (4754-2946) if you thing something is injured or doing it tough,” he said.

The national park south of the Great Western Highway, and the lookout at Govetts Leap, are open to visitors. For information on closures call 4787-8877 or visit www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au’

.

.

Mismanagement?

.

So the silence from the firies, from Bushfire Management and from the New South Wales Government ultimately responsible and accountable, was deafening. It was as if the entire Firie fraternity had gone to ground in a code of silence behind closed doors.

So naturally the community response was that something smelt fishy. This communication intransigence was a public relations blunder by Bushfire Management, to its detriment.

Then filtered out accounts of crazy operational mismanagement during the bushfire and of bush arson by the firies behind the roadblocks beyond the public gaze.

- Rumours circulated that the initial ignition had been left for burn in the critical first few days of 13th November and 14th November up on Burra Korrain Ridge because it wasn’t right next to a road so that fire trucks could get to it. The fire had even been abandonned. Then the wind picked up and it spread. Airborne firefighting was not called in until a Section 44 incident declaration was effected on 15th November.

- A second fire nearby to the west near Hartley Vale, purported also lit by dry lightning on 14th Nov, had attracted broadscale backburning from the Hartley Vale Road. But the backburn got out of control, ripped up the valley fanned by winds and crossed over the Darling Causeway on to the Blackheath Escarpment and the Upper Grose to join up with the first blaze. The onground evidence shows that this was a hazard reduction burn starting from alongside the Hartley Vale Road just east of the village of Hartley Vale.

- Then came the account of senior bushfire management at the Rural Fire Service headquarters at Homebush ordering a ‘headburning’ a new 10km fire front along the south of the Bells Line of Road into the Grose Valley. Perhaps the NSW Government had stepped in demanding action. Perhaps RFS headquarters response was a series of overreactions, albeit too late and to be seen to be now ‘acting’ was only compounding the fire risk to the Grose . Apparently, the RFS Commissioner had even touted imposing a massive defacto hazard reduction north of the Bells Line of Road right though the vast wilderness of the Wollemi National Park, to somehow head off another fire on 20th November some 80km away north of Wiseman’s Ferry, but that strategy was rejected in a heated operational debate. [“The Wollemi National Park is part of the World Heritage Area and covers 488,620 hectares. Important values of the park include the spectacular wild and rugged scenery, its geological heritage values, its diversity of natural environments, the occurrence of many threatened or restricted native plant and animal species including the Wollemi pine and the broad-headed snake, significant plant communities, the presence of a range of important Aboriginal sites and the park’s historic places which are recognised for their regional and national significance.” – Wollemi NP Plan of Management, April 2001]

- Even the Zig Zag tourist railway station was apparently accidently firebombed by an overzealous airborne firefighter starting backburning en mass

- Then came the account of Blackheath residents who had their houses subjected to the risk of a deliberately lit backburn during the course of the bushfire. Despite the out of control wildfire being many miles to the north west of Blackheath, a broadscale backburn (some say is was really a ‘defacto hazard reduction‘) was lit along the fire trail below the electricity transmission line near Govetts Leap lookout. But it got out of control briefly and threatened to burn houses in Connaught Road. Indeed the entire Blackheath Escarpment fire from Hat Hill Road south through Govetts Leap Lookout and Ebans Head was started deliberately as a ‘strategic’ backburn.

Blackheath Escarpment completely burnt (top) for hectares, looking south from Hat Hill Road

(Photo by editor 20061209, free in public domain, click image to enlarge) Blackheath Escarpment completely burnt (top) for hectares, looking south from Hat Hill Road

(Photo by editor 20061209, free in public domain, click image to enlarge)

.

The rural property east of Hartley Vale where on 20070207 there was clear evidence of hazard reduction (HR)

commencing only from the south side Hartley Vale Road, opposite.

Eucalypts were burned only at the base, but further up the hill the tree crowns had been burned.

The HR had quickly got out of control and then crossed over the Darling Causeway.

(Photo by editor 20070207, free in public domain, click image to enlarge) The rural property east of Hartley Vale where on 20070207 there was clear evidence of hazard reduction (HR)

commencing only from the south side Hartley Vale Road, opposite.

Eucalypts were burned only at the base, but further up the hill the tree crowns had been burned.

The HR had quickly got out of control and then crossed over the Darling Causeway.

(Photo by editor 20070207, free in public domain, click image to enlarge)

.

Once two weeks had passed since the dramatic firestorm and with only silence emanating from Bushfire Management and the NSW Government, local people had had enough and they wanted answers.

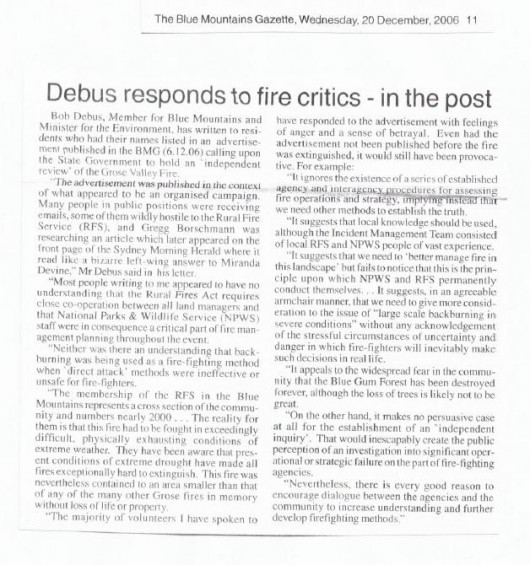

Some 143 local yet disparate conservationists via ‘jungle drums’ met up, discussed the issue, united informally and agreed to go public. They informally formed the ‘Grose Fire Group‘ and contributed to a fighting fund some $1700 odd and became vocal. Two weeks after the Grose Valley Firestorm the Grose Fire Group managed a full page open letter in the local Blue Mountains Gazette on 20061206 on page 13. It was directed to the ultimate authority responsible and accountable for the Grose Fire Tragedy, the NSW Government. The Premier at the time was Labor’s Morris Iemma MP. The NSW Member for the NSW Seat of Blue Mountains as well as NSW Minister for Environment at the time was Bob Debus MP.

Those who valued the Blue Gum Forest challenged those responsible for its protection. The tragedy certainly stirred and polarised the Blue Mountains community. Conservationists naturally wanted answers, an enquiry, a review of bushfire prevention and management from:

- NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service under the direction of Regional Director Geoff Luscombe

- NSW Rural Fire Service under the direction of Commissioner Phil Koperberg

- Blue Mountains Bushfire Management Committee aligned with Blue Mountains City Council and chaired by Councillor Chris Van Der Kley.

.

‘Grose Valley Fire – World Heritage takes a hit’

“The Blue Gum Forest, birth-place of the modern conservation movement, was badly damaged by the Grose fire on Wednesday the 22nd of November. If this precious forest was a row of houses, then there would automatically be a major investigation into how the fire was fought. The fact that this major loss of our natural heritage is only now becoming known is testimony to the prevailing attitudes of those controlled the media spin during this recent fire event,” said Keith Muir director of the Colong Foundation for Wilderness.

“Until today the overall perception from the media was that this fire was a good one. No houses or lives lost”, Mr Muir said.

“There where no media updates on the struggle to save Blue Gum. No the reports of success in saving fire sensitive rare plants and rainforests along the escarpment edge. All the media reports spoke of bushland burnt; not on the success of any strategy to minimise the impact on the World Heritage listed national park, while saving lives and property”, he said.

“The Blue Mountains National Park Fire Management Strategy 2004 sets out all the necessary actions to protect the natural environment, as well as life and property. Yet for some reason it appears at this stage that the fire was not fought according to that agreed Strategy, as far as its provisions on natural heritage were concerned”, said Mr Muir.

“Increased fire is a major threat to World Heritage values of the Greater Blue Mountains national parks. Unless we develop and implement better strategies to defend the bush, as well as lives and property, then climate change will make this threat much worse,” Mr Muir said.

“The fire management strategies and techniques undertaken during the fire need to be re-examined to ensure the diversity of the Blue Mountains forests is protected into the future,” he said.

“Future fire management requires the feedback that only an inquiry into the Grose Valley Fire can achieve. Such an inquiry should not be taken as a criticism of those involved in fighting fire. It is an opportunity to ensure that everyone stays on fully board with future efforts to minimise fire damages,” Mr Muir said.’

[Source: Colong Foundation for Wilderness, ^http://www.colongwilderness.org.au/media-releases/2006/12/grose-valley-fire-%E2%80%93-world-heritage-takes-hit]. The magnificent rich carpeted Gross Valley, as it was

(compare with the lead photo at the start of this article, click image to enlarge) The magnificent rich carpeted Gross Valley, as it was

(compare with the lead photo at the start of this article, click image to enlarge)

.

What exacerbated the conflict was not some much that the bushfire had got out of control and had raged through the precious Grose Valley per se, but it was more the defensive, aloof reaction by ‘Firies’ which escalated into a barrage of defensive and vocal acrimony against any form of criticism of the firefighters.

In the face of such palatable denial by the Firies,of any accountability the initial shock and sadness within the local community within days quickly manifested into outrage and anger, and even to blame and accusations.

Most conservationists however felt a right to question and seek specific answers from Bushfire Management about the Grose Fires, for lessons to be learned, for fundamental changes to be made to bushfire management policy, bushfire fighting resourcing and practices, all simply so that such a tragedy should not be repeated.

But the key problem was that the ‘Firies‘ adopted an ‘in denial’ approach to a community suffering loss. Many Firies denied that they had done anything wrong and rejected any criticism by conservationists. Some Firies vented their anger in the local media attacking anyone who dared criticise. Clearly, Bushfiore Management’s debriefing and review of the bushfire in its immediate aftermath was poorly managed.

Underlying the conflict was the Firies urban fire fighting mandate to ‘protect lives and property” – that is human ones, not forests, not wildlife. Whereas what emerged with many in the Blue Mountains community was the implicit expectation that the World Heritage Area is an important natural asset to be protected, including from devastating bushfire.

The Grose Valley

Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area The Grose Valley

Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area

.

Hence, it was a conflict between differing cultural value systems. It was about recognition of the value of the natural assets of the Blue Gum Forest and the Grose Valley within the Bue Mountains National Park within the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

The iconic Blue Gum Forest

(Acacia Flat, before the pyrocumulus firestorm of 22nd November 2006) The iconic Blue Gum Forest

(Acacia Flat, before the pyrocumulus firestorm of 22nd November 2006)

.

The iconic Blue Gum Forest

(The aftermath) The iconic Blue Gum Forest

(The aftermath)

.

20 Sep: (2 months prior)…‘Fire crews prepare’

[Source: ‘Fire crews prepare’, Blue Mountains Gazette, 20060926]

.

‘With warmer days just around the corner and continuing dry weather the Blue Mountains Region National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is again undertaking rigorous preparation for the coming fire season.

“Every year around this time the NPWS run a number of fire preparedness days to ensure staff and fire-fighting equipment are fully prepared for the season ahead,” said Minister for Environment Mr Bob Debus.

NSW Labor Minister for Environment

Mr Bob Debus MP NSW Labor Minister for Environment

Mr Bob Debus MP

.

“Fire preparedness days require fire-fighting staff to check their personal protective equipment, inspect fire-fighting pumps and vehicles and ensure that communication equipment and procedures are in place and working before the fire season begins.”

Mr Debus said a number of exercises, including four-wheel drive and tanker driving, first aid scenarios, entrapment and burnovers, were also employed to re-familiarise staff with all aspects of fighting fires.

“Burnovers, where fire-fighters are trapped in a vehicle as fire passes over it, is one of the worst case scenarios a fire-fighter can face so pre-season practice is critical to ensure that their response is second nature”, he said. “Local fire-fighters have also undergone stringent fitness assessments to make sure they are prepared for the physical demands of fire-fighting – like being winched from a helicopter into remote areas with heavy equipment, to work long hours under very hot and dry conditions wearing considerable layers of protective clothing”, Mr Debus explained.

Mr Debus said that fire preparedness and fitness assessment days worked in conjunction with a number of other initiatives as part of a year-long readiness campaign for the approaching summer.

“Over the past 12 months, NPWS officers have conducted more than 150 hazard reduction burns on national park land across NSW.”

.

“Nineteen hazard reduction burns have been conducted in the Blue Mountains region covering nmore than 4500 ha” ~Bob Debus MP

.

Mr Debus said that while fire-fighting authorities are preparing themselves to be as ready as possible for flare ups and major fires, home-owners in fire prone areas of teh Blue Mountains should also be readying themselves for the approaching season. “Now is the time to start cleaning gutters, ember proof houses and sheds, prepare fire breaks and clear grass and fuel away from structures”, he said.’

.

20 Nov: ‘Bushfires rage closer’

[Source: ‘Bushfires rage closer’, by Dylan Welch and Edmund Tadros, Sydney Morning Herald (with Les Kennedy and AAP), 20061120, ^http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2006/11/21/1163871368365.html?from=top5]

.

Wisemans Ferry: